© Virginia Wilcox

Virginia Wilcox's new book Arboreal, published by Deadbeat Club shows a sinewed relationship between Los Angeles trees and the sprawling landscape they inhabit.

Spidery branches look over and onto highways, pointing and wrapping like withered fingers. Their power is in the space around them, their conversation with the land, the occasional person sitting for a portrait, or the built human presence for which they continue to make space.

“These images present a survey of trees inhabiting a mangled urban landscape that looks something like wilderness,” writes Wilcox. The work does more than simply note urban development's impact on nature - it portrays a melancholic meditation on coexistence. A mirror leans against a palm tree reflecting bramble and sky behind it; a stand of baron trunks mimics a distant downtown skyline; a pathway stretches to reveal an anonymous figure on a park bench who almost disappears in their knotty camouflage.

As a collection of images, Arboreal is a quest for coexistence in an increasingly hostile world, and Wilcox’s soft, wistful way of seeing creates entry points from many angles.

I spoke with Wilcox to learn more about the book and her life within it.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Virginia Wilcox

© Virginia Wilcox

Jon Feinstein: How did this project start and what was the first image you made for it?

Virginia Wilcox: I started this project during my first year of living in LA, which was also the first year of my MFA at The University of Hartford. At the time, I felt lost and ungrounded, struggling to make sense of this new place and how I fit into it. Seeking escape and quiet, I began making work in parks, from small flat parks and trails in The Valley overlooking residential housing to seemingly endless parks that offered views high above the city.

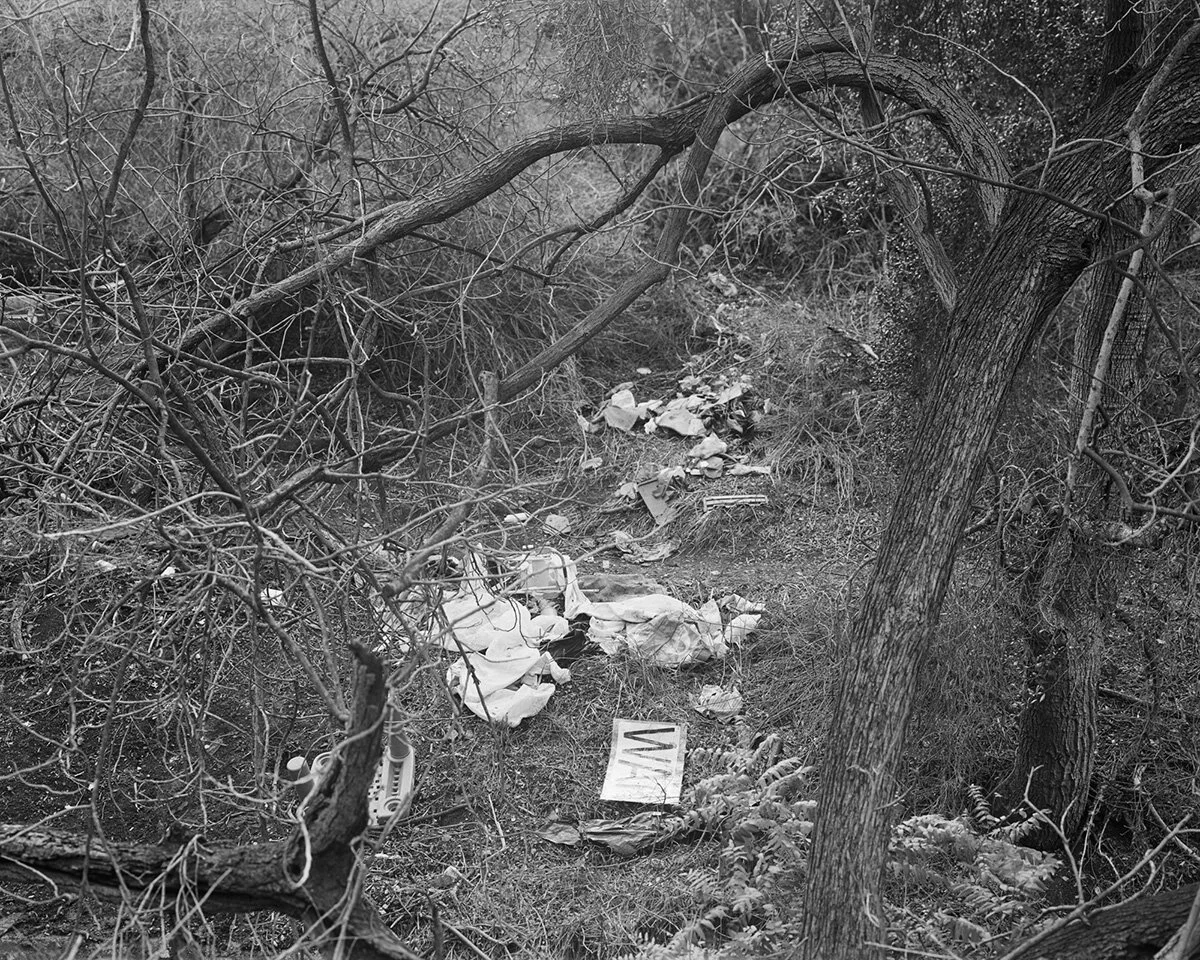

The image below is from my very first shoot, taken in Ernest Debbs park in the early Spring of 2016. I became transfixed by the wildness of these larger elevated parks where I felt a tension between the beautiful, formal landscape and interruptions of everyday objects like sewer drains, concrete pathways, and trash, all reminders from the sprawling city below.

© Virginia Wilcox

© Virginia Wilcox

Feinstein: I think it's interesting to think of this work in LA in relation to your relationship with the Pacific Northwest. Trees have such a different vibe/ psychological implication in both landscapes. Was this on your mind when making this work?

Wilcox: Yes, completely. When I first moved to LA, I was constantly searching for shade and felt unaccustomed to living in a place without evergreen trees punctuating the landscape. In my hometown of Seattle, I could always identify East and West based upon the Cascade and Olympic mountains, the Puget Sound, and the lakes throughout the city. On the Eastside of LA I had no parallel identifiers, just a maze of new freeways to navigate.

I shot the majority of this project in Elysian Park, which sits above the city in my neighborhood of Echo Park. The trees here felt scraggly and untamed. I would often find palms that had spontaneously lit on fire, leaving black scorched spots on their trunks. I found these aesthetic differences fascinating. There were entire forgotten areas that unveiled new surprises on each of my visits.

© Virginia Wilcox

Feinstein: This might be an obvious or simplistic question, but why black and white?

Wilcox: The first few pictures I made for this project were actually on color film, but I quickly saw that they needed to be in black and white. The pictures in Arboreal are primarily concerned with light and form. Black and white emphasizes these qualities, guiding the eye through the frame in a very particular way. There is a specific way that black and white film renders Southern California light. The result is softer and less harsh, which gives a quietness to these images.

© Virginia Wilcox

Feinstein: On one level, this is about human presence and nature, but my hunch is that it goes deeper for you personally. Where you are in all of this?

Wilcox: While humans are integral to this body of work, I was most interested in their exploration of this space and the mark they left on it. When making this work, I obsessed over the idea of what might have happened in a certain scene; how a patch of scorched earth had caught fire, why a gold lamé purse was left emptied and inside out in a field of grass. My journey through this space often felt like following a trail of breadcrumbs.

I was heavily influenced by New Topographics photographers, particularly Robert Adams. In Arboreal, the natural landscape of the park and this dense developed city are in a constant tug of war. While the city is tightly managed by all the aspects of its capitalist economy, the park space is more free to make its aliveness visible.

© Virginia Wilcox

© Virginia Wilcox

Feinstein: These are mostly landscapes, but there are a few scattered portraits in the mix. What’s their role in all of this?

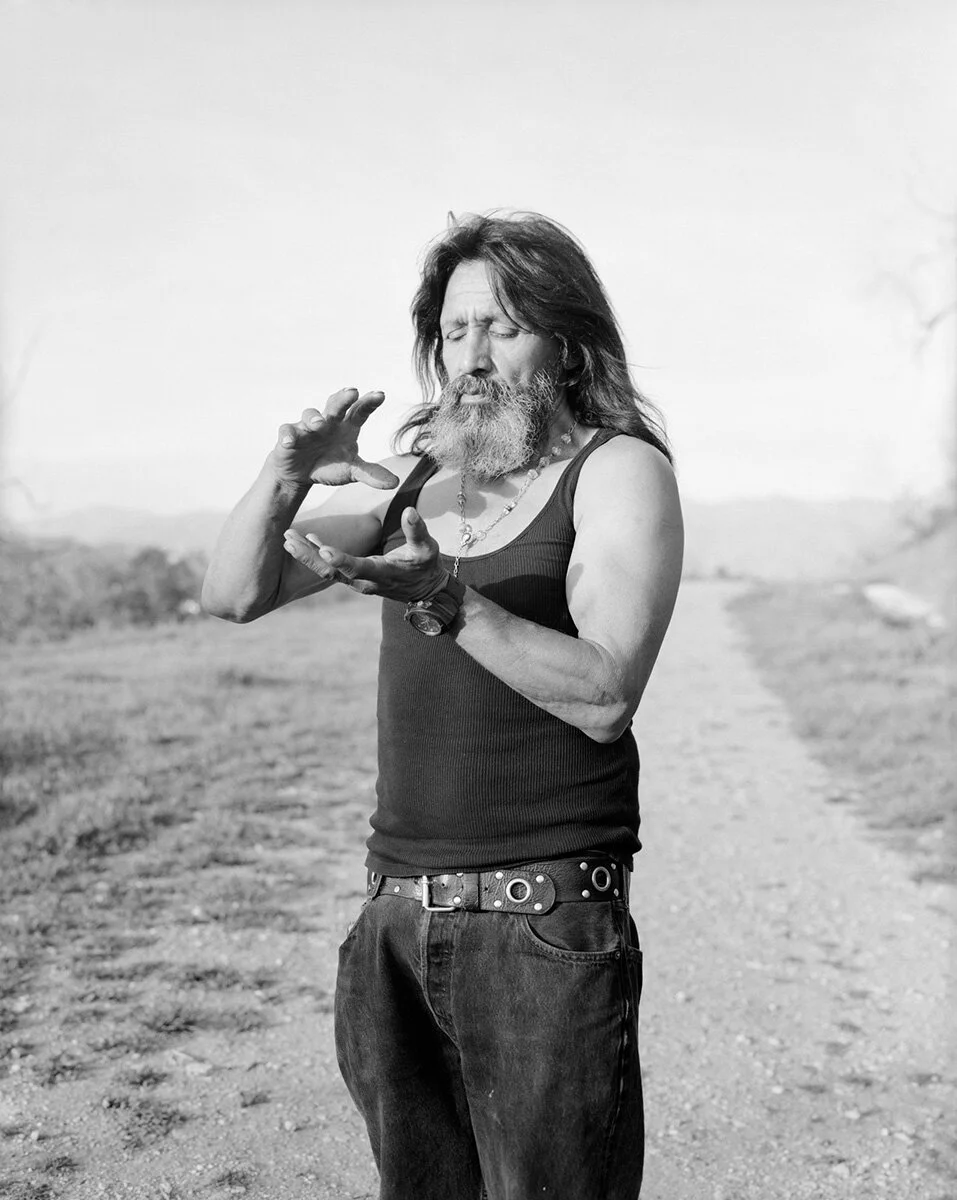

Wilcox: While there are only two formal portraits in the book, both subjects play a central role as guides on this journey. I met my first subject, Jesse Jesus (pictured below) early on in the project, and our collaboration shaped much of the work to come. At the time, Jesse lived in Sycamore Park. We developed a friendship, and collaborated on several occasions. Jesse showed me his world, leading me up shortcuts over drainpipes and pointing out where a man had crashed his motorcycle on the 110 freeway, flying thirty feet in the air and landing in the Arroyo Seco below.

His stories confirmed the sense of melancholy I felt in the park. Jesse is a religious man and felt that God was present in every tree. His spiritual connection to this place added new layers of meaning to the landscape for me.

Three years later, and in the middle of the pandemic, I met Roger. For a long time, I was searching for that final picture, something to give closure to this meditative exploration of the park. His portrait is the last picture I took for Arboreal, and the last exposure on our walk through Elysian. The sun was coming down to the point that I could barely see through the ground glass, and a patch of light illuminated his face.

© Virginia Wilcox

Feinstein: In many of these images, I see a relationship to landscape painting....are you looking at painting at all?

Wilcox: I am lucky to have a mother who studied art history and took me all over the world to art museums as a kid. The idea of the romantic/utopian landscape was imbued in me from an early age, influencing the way I looked at nature, and later, the way I photographed. This notion comes up in the work, bringing to mind paintings from The Hudson River School painters, particularly Thomas Cole.

Romantic art includes pristine “natural” landscapes, but also the ruins of long-gone civilisations. In these landscapes, humans are miniaturized and the world around them is vast, implying that human’s smallness not only has to do with the space they occupy, but also the brief moment of time they are on this earth.

Feinstein: I think/ recall you work mainly in large format -- assuming I'm right, can you talk a bit about its significance to your practice?

Wilcox: I do. I have been using the same Wista 4x5 camera since graduating from Bard over a decade ago.

Feinstein: I remember learning on a Wista when I was at Bard. I feel like it’s the “Bard” camera!

Wilcox: My camera and gear are heavy and cumbersome, which forces me to navigate the landscape slowly and with intentionality. The manual nature of the 4x5 allows me to make quiet observations and methodically consider every element of the frame. Looking through the ground glass, the upside-down and backward appearance of the image allows me to construct (rather than simply capture) what is in front of me.

I often spend twenty minutes working on a single frame, waiting for the wind to slow or the light to hit a tree limb in a particular way. People are often surprised that my personality is so different from my work. I am a pretty fast-talking/fast-paced person, and being out in the park alone with the view camera is one of the only things that truly slows me down, and the pictures show a side of me that few witness.

© Virginia Wilcox

Feinstein: A tangent on this idea, but thinking about time, distance and looking: in your statement, you use the word "a suggestion of infinity" -- can you elaborate on this?

Wilcox: Many of these images offer views of the city that go on and on to the point where the cityscape meets the horizon line, suggesting that there is no end to this built environment. At a macro level, Los Angeles’s sprawl is only slowly growing, but on a micro-level, it is under constant change, decay, and evolution. The park is slowly changing in relation to what is out in the city.

© Virginia Wilcox

Feinstein: Much, if not all of this work was made prior to the pandemic (and more outwardly/public reckoning on racism in America). Do these events impact, influence, etc how you see this work, the landscape, and its metaphors?

Wilcox: Yes, completely. This past year has changed the way I look at almost everything. This past March, hundreds of cops in riot gear arrived at Echo Park lake to fence off the park and evict my unhoused neighbors who had been safely living at the lake during the pandemic (more here.) These encampments existed because our system has failed to support its most vulnerable people. This community had created its own ecosystem, building showers, a community garden, and establishing systems to clean the park when the Parks Department refused to clean up “homeless detritus.”

Many of the cops who showed up were unmasked, risking COVID exposure to unhoused people and protesters. All cops were fully armed with guns and batons, and as the night drew on, there were countless acts of police brutality and illegal arrests, including members of the press and legal observers.

This led me to think about parks, their intended uses, and the idealistic notion that they are democratic spaces. This historical moment sent the strong message that public land is not designed for all people. If you travel from park to park across LA, you will notice a dramatic level of disparity in maintenance and upkeep depending on the wealth of the surrounding area. Since Echo Park’s gentrification, this once heavily graffitied park has become a priority to the city. Nearby home values now exceed 2 million dollars. These events hit hard for me.

Throughout this project, I have developed friendships with folks who live in nearby parks, Echo Park included. These parks are magical because of the people who make their mark on them, stringing flags from trees, building rose gardens outside their dwellings, and ultimately creating a free space that is not planned or designed to be profitable or controlled by anyone but those who call it home.