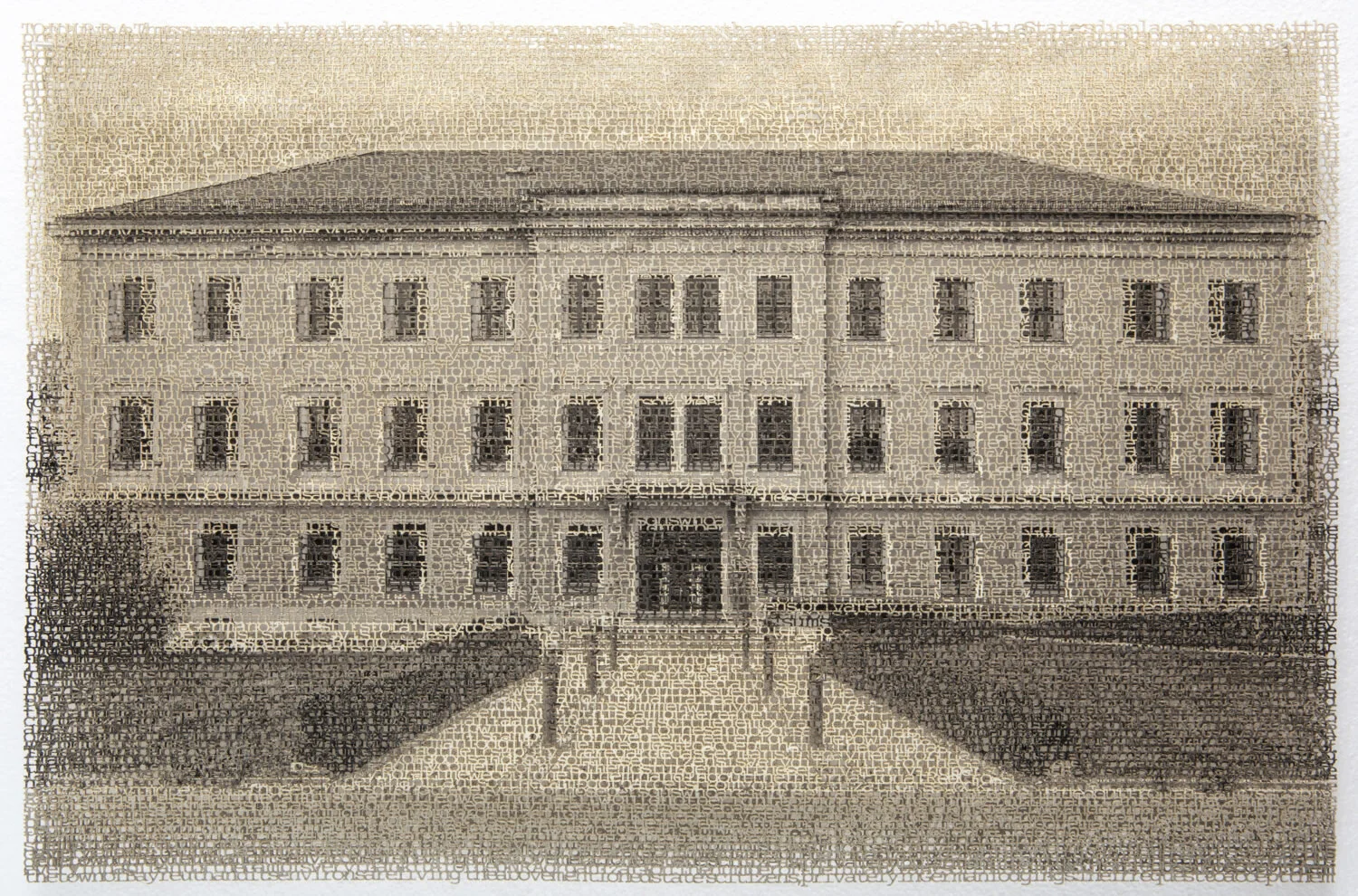

© Krista Svalbonas, 2020 from the series What Remains

Born in the United States to Baltic refugees, Krista Svalbonas’ complicated identity permeates her photography. Dual ties to Latvia and the United States, the languages she spoke growing up, and her relationship to architecture's psychological imprint on home and dislocation are the driving force behind her work.

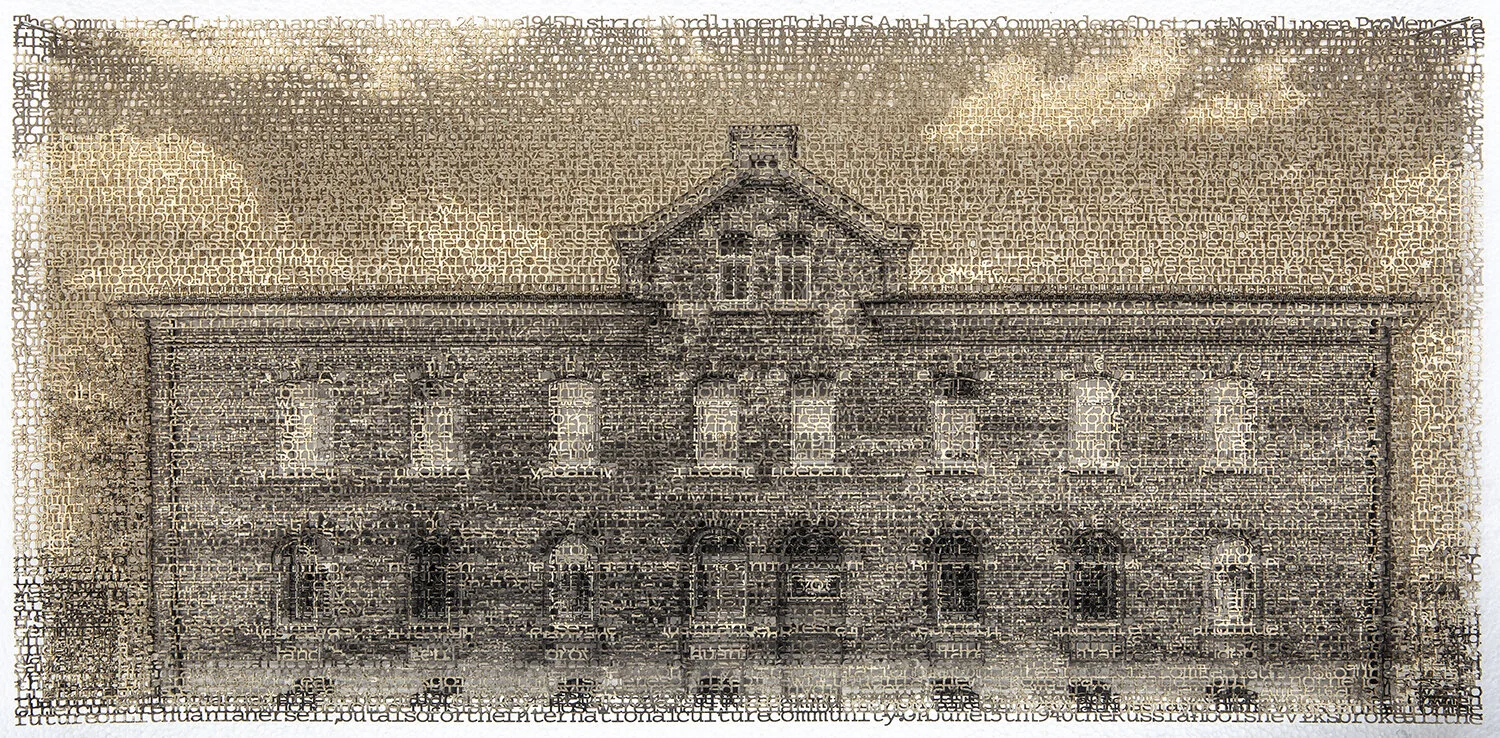

Krista Svalbonas uses intricate techniques to reference architecture and design movements as they affect and reflect culture, struggle, and totalitarian rule. Her latest series, What Remains overlays laser-cut, traditional Baltic textile designs atop typological black and white photographs of buildings in Soviet-occupied Baltic cities. For Svalbonas, this fusion of cold structures with a nod to folk art and craft is a symbolic "counterpoint to Soviet-era architecture and the memory of its totalitarian agenda."

As conversations around cultural diaspora and displacement take center stage, Svalbonas' work is increasingly relevant and worth exploring. After having the pleasure of reviewing her work at Denver's Month of Photography Portfolio Reviews and including her in Humble's Diaspora Studies exhibition with The Curated Fridge, we caught up to discuss the many angles of her work.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Krista Svalbonas

© Krista Svlabonas, 2020 from the series What Remains

Jon Feinstein: Your work has so many layers to it - but what brings everything together across bodies of work is the connection and relationship between architecture, intervention, and (your experience with) diaspora.

Krista Svalbonas: I have been interested in ideas surrounding home and place for a long time now. This interest definitely stems from being a daughter of refugees. I have always felt a sense of duality in my identity as both American and Baltic. I grew up speaking Latvian, going to Latvian Saturday school, going to Latvian camp in the summers and attending large festivals with individuals from all the Baltic countries. There was a concerted effort in my upbringing to connect to all that was lost when my parents and grandparents fled Latvia and Lithuania to avoid Soviet occupation.

Bayreuth 1, 2018 from the series Displacement © Krista Svalbonas

Feinstein: Can you talk a bit about how these threads collide for you? Why is it important to interweave them from project to project?

Svalbonas: I think my work has been a continual discovery of who I am, where I belong, and how to make sense of the world around me. These threads of architecture, diaspora and place persist in different bodies of work as I continue to question these ideas in my own identity and as I learn to literally make images that answer these questions.

Feinstein: In your recent work, you've been using laser cutters. When did you start introducing it into your work?

Svalbonas: I started using a laser cutter with my series Displacement which focuses on Baltic refugee camps in Germany after WWII. I had come back from my first visit to Germany, locating these spaces, and had no idea how I wanted to approach the work. The buildings themselves weren’t remarkable spaces and I was constantly reminded, while documenting them, how little they spoke of the tumultuous past and the fragile lives that inhabited them. I was also reading and re-reading plea letters that I found at various archives in my search for these spaces.

Augsburg Haunstetten, 2019 from the series Displacement © Krista Svalbonas

Feinstein: What draws you to the process?

Svalbonas: At the time I was printing the images, I was being trained to use a laser cutter. Something just clicked in my mind to try and combine my images with the text from those letters. From that idea forward, I spent about a year figuring out exactly how to do that. Needless to say, I got very good at laser cutting! It felt like a natural progression to continue this process in my What Remains series, after all, I am talking about the same time period and the same history, which revolves around the same trauma.

Emden 1, 2019 from the series Displacement © Krista Svalbonas

Feinstein: Can you talk a bit about the specific (Baltic) origins of these designs and their significance

Svalbonas: The textile patterns in the series are traditional folk-art patterns from the Baltic countries. The patterns themselves are used in a variety of ways, in mittens, scarves, table cloths, traditional folk costumes and curtains. The symbols themselves originate from a time period where pagan traditions were practiced. Many of the symbols reference the mystery and power of mother nature.

Feinstein: Making these in black and white feels like such a conscious/intentional decision...

Svalbonas: Converting the images to black and white definitely was a very conscious decision. Black and white imagery is often associated with representing history. I also wanted the viewer to focus on the two elements of importance, the buildings and the patterns. I felt adding color would just distract from that.

© Krista Svalbonas, 2020 from the series What Remains

Feinstein: Do you consider yourself a "photographer" or an "artist working with photography" and do these categories even matter?

Svalbonas: I consider myself an artist, but I’m not very fond of labels in general. I find them confining and a bit limiting. I often work photographically, but I have also produced bodies of work in painting and sculpture.

Feinstein: Much, if not all of your work is about your family experience/ diaspora as Latvian refugees and your work has been widely exhibited, both in the United States and will soon travel to Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Do you see the work having a different resonation, response, place or role when exhibited in the US vs the regions whose history it navigates?

Svalbonas: The response to the Displacement work has been immensely positive. The Baltic community in the US has been very supportive by awarding me grants and providing other sources of sponsorship. The project started with a kickstarter-esque platform where both my artist and baltic community really rallied to help get enough funding to start my documentation in Germany. Now that work has been produced and is starting to be exhibited, that support is continuing in various ways.

I’m often asked how I find the refugees that I interview and photograph. I find them through social media via their children and grandchildren. I’m so heartened by the fact that younger generations realize how important it is to preserve these stories and this history. I receive a lot of thank you letters and messages from all over the world. In the wider audience for this work, there is also a lot of positive feedback. I often have individuals tell me that they had no idea this history existed and that’s a significant part of why I make the work. I recognize this is a little known story, but it is something that is so very important to tell.

Feinstein: How do you think this work sits uniquely within the context of global division and the rise of populist movements over the past decade?

Svalbonas: This question made me think about this short film (embedded below) that was sent to me recently. The film has a few minutes of some archival footage of one of the refugee camps that I documented, which is very rare to find. Interestingly enough, I also interviewed and photographed one of the refugees that appears in the film as a young boy.

Watching the film and also hearing the stories of these refugees, drove home that these fears and the resentment of “the other” is nothing new. These beliefs have driven political history for a very long time now. I think the work I produce brings to light this little-known history and it also helps frame contemporary forced migration.

One of the camps I documented in Wurzburg, Germany was a former military barracks. It stood empty for about 30 years until about 2014, two years prior to my documenting the space, I discovered it was being used to shelter Syrian refugees. I witnessed this in other German cities as well, history was very visibly and tangibly repeating. History remains our greatest teacher. I would hope that the work I make reinforces that and educates the viewer about our collective past.

Feinstein: Getting deeper into your personal experience - you are a child of WW2 immigrants, and you describe how your parents' relationship to architecture was incredibly cultural and political and a framework for your own identity growing up. Can you expand on your series that deals with your own experience with architecture?

Svalbonas: I have two series that focus on my own architectural history, Migrants and Migrator. Both series began with photographs I took in the three locations I have called home in the past eight years: the New York metro area, rural Pennsylvania, and Chicago. Each image is a visual sketch of the genius loci of the landscape at a particular moment in my history.

I cut and reassembled the images in sets of three, creating hybrid structures that reinterpret and reinvent architecture, disrupting space, light, and direction. At the same time, because the triangle is the simplest stable two-dimensional form, anchoring each piece in three geographical points creates a stability that acts as counterweight to the sense of dislocation. Both bodies of work turn an analytical gaze on the architecture of my past and present while offering a personal reflection on the nature of home. In retrospect, both series pushed me to delve even deeper into my family history.

© Krista Svalbonas from the series Migrants

Feinstein: You describe your work as a "composite of my own experience and the fading memories of my parents and their generation" - can you expand on this?

Svalbonas: Growing up, I knew my parents were refugees or Displaced Persons, as they were formerly called. I also knew why they fled the Baltic countries and I knew they spent time in Displaced Person camps. I knew these facts but I never knew what that really meant. Until I started making this work and researching this history, I had no idea what a Displaced Person camp really was, or how precarious and fragile of an existence my family had after the war.

This summer, I’m finishing a tour of the US and Canada, interviewing and photographing refugees that were housed in the camps I have documented. This was something that I wanted to finish last summer, which Covid-19 inevitably postponed. As you can imagine, there are very few individuals left with first-hand knowledge of this time period, and most of those individuals were children or teens at the time. Their account of these events is vastly different from those who were adults at that time. Memories are tenuous, fragmented and frail. I would often find myself for hours or days down a rabbit hole, piecing together bits of information from archives and first-hand experiences.

The work is definitely a collaboration between what I have been able to discover and gaps filled in by those who lived through this time period. I also feel like I am racing against time to complete this work as I have sadly lost people before I was able to visit and interview them. I have also lost people after having visited them, which is equally heartbreaking. While traveling Germany, I was introduced to the word Zeitzeuge. There isn’t a direct translation into English, but it basically means “time witness”. I am constantly aware of this history being lost, and am in a constant momentum to preserve it by documenting the stories of these time witnesses.

Ansbach 2, 2018 © Krista Svalbonas. From the series Displacement

Feinstein: Can you expand on how this work helped you to resolve and better understand these cultural/historical puzzles?

Svalbonas: When creating my work, I am so very aware of history. To produce the Displacement work, it took me about a year of research to find these spaces, as they aren’t very well cataloged or documented. The research really helped me fully understand this history, and traveling to the sites of these camps made the history come alive. I finally understood what Displaced Person camps were, the struggles the refugees faced, and the trepidation and joy they felt emigrating to their new home countries.