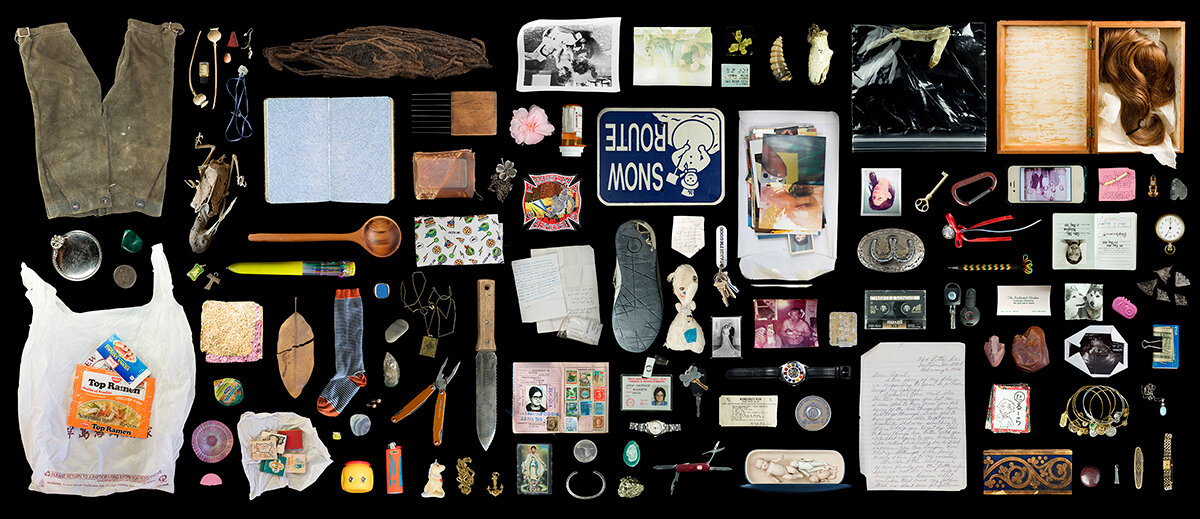

© Kija Lucas. Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, vitrine #7, Archival Pigment Print 32x74", 2014-2020

The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy, a roving photography exhibition created by Kija Lucas, showcases the emotional power of objects – those we cherish and those we carry that house memory and meaning.

When my wife and I prepared to move from San Francisco to Berkeley nearly three years ago, I paused to think about one of the items that sits on my desk: a small, painted wooden bird sculpture that fits comfortably in the palm of my hand. This orange, black, and turquoise token has been with me for 35 years. I vividly recall the face of the young woman who offered it as a parting gift at the end of her eighth-grade birthday party. Ann’s genuine smile suggested that I - a mouthy, atheist social outcast with unpopular opinions about Utah’s dominant religion - was welcome in a cool girl’s house.

Why do we hold onto objects that are emotionally potent, but carry no monetary value?

Whether the associated memories are happy or sad, why do we accept the material burden that the items pose?

These are two of the underlying questions that shape photographer Kija Lucas’s project The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy (MoST), Lucas’s crowd-sourced project visually coalesces sentimental objects brought in by participants. Looking at the large composite prints, it’s alluring to speculate about the objects and the strangers who possess them. Lucas resists that pull, thinking instead about wider contexts, particularly archiving as a remnant of settler-colonialism.

I spoke with Lucas about the project, which is on view at California Institute of Integral Studies through May 16th, its origin, and how it eludes familiar institutional archival practices and the resulting production of knowledge.

Roula Seikaly in conversation with Kija Lucas

Installation photo © Deirdre Visser

Roula Seikaly: Can you describe The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy? Its origin and evolution?

Kija Lucas: Sure, so The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy, also known as Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, comprises photographs of people's sentimental objects. I've photographed the items in locations around the country, and the most recent exhibition was staged at California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS).

The images are edited and printed all on one page, and then framed or hung from brackets or presented in a vitrine. It is similar to what you would see in a museum, sort of a maximalist presentation where the objects are really close together. I also collect the stories behind the objects. I ask them a few questions about themselves and the objects they brought in. When this project started, I was thinking about why people hold onto things, and the aura that is associated with the objects, and how that is loaded with personal meaning.

When I started this project, I was also making work about my grandmother and her experience of Alzheimer’s Disease. I was paying attention to what she was holding on to as well.

© Kija Lucas Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, Drawer #7, Archival pigment print, 17x26" 2018

Seikaly: Is there any overlap between the two projects?

Lucas: Actually yeah, first they were two branches of the same project.

Seikaly: Talk more about that, please.

Lucas: They started off both called Objects To Remember You By, one was an index of sentimental objects, and the other one was Collections from Sundown. I photographed objects that she would carry and notes she made for herself. For both projects, I think about the emotions attached to physical items, how it’s both comforting or familiar and burdensome at times.

Seikaly: What motivated you to differentiate the projects?

Lucas: There was a point where it became evident that these projects were two different things. I was not planning to exhibit them together, and making the work was happening in such a different way. Going to my grandmother’s house to photograph, and photographing in my studio, was a very solo endeavor. Asking the public to participate in the work, and photographing in a public space was an extroverted experience (how do I say outward way of working… I don’t have this word)

© Kija Lucas. Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, Shelf #2, Archival pigment print, 32x48" 2015-2020

Seikaly: How do participants learn about this opportunity? I’m guessing word of mouth is a useful driver, and promotion by the hosting sites. Is that accurate?

Lucas: Yes, it began with word of mouth. I ask the hosting sites to put the word out and use social media to try and get more folks to participate.

Seikaly: Can you describe the process of aggregating the images and then creating the composite prints?

Lucas: Ha! I think if a professional archivist or registrar saw my process, it would give them nightmares. I have hard drives that house the works organized by place. I usually edit each object photograph separately. Those are published on the website with the intake information from the person who brought it in to be photographed.

I approach the composite images in a few ways. Place, where the objects were photographed. Time, when they were photographed. Shape and size, I often start by knowing the size of the final piece. I arrange the objects based on those dimensions and add objects photographed in various times and places based on how they fit into the piece. I should add representation to that. I want to make sure that a number of communities are represented either in a piece or in an exhibit.

Installation photo © Deirdre Visser

Seikaly: Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy has a social practice aspect to it. Is that a significant driver in your overall creative practice?

Lucas: No. The social practice aspect was incredibly intimidating to me in the beginning. I often work on my own. I have found that the interactions with participants, while they cannot be seen in the work, are one of the most important aspects of this body of work. They are what drives it and keeps it interesting and important for me.

Seikaly: Something came up when I interviewed you for the KQED review, and again as we prepared for SPE that might be interesting to get into now. You’re an archivist, but not a collector. The objects are yours in a virtual context, but you don’t carry the emotional or psychological meaning attached to them. Can you talk about that aspect of the Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy?

Lucas: I have a lot of feelings about museums and the colonial impulse to collect and own, and what ownership of certain histories and certain objects is. Museums hold onto the actual thing, assigning monetary and provenance value to it. I'm only interested in the sentimental value of a thing. And I'm only interested in photographing it. I photograph them without measurement and from memory, and that reminds the viewer that it's not the actual thing. We're looking at a representation of that thing, whereas the object is a representation of the person’s feeling or related emotion.

I feel like each person has a history that should be told. I am a collector in a way because I photograph these things, and I care for them and the related stories. Maybe it's taking some of the burden, for just that minute when I photograph it, and for somebody to tell the story of a thing that maybe they haven't told before. But, the objects go home with their owner. I don't have any desire to be responsible for them.

© Kija Lucas. Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, Shelf #1, Archival pigment print, 32x48" 2014-2020

Seikaly: It’s a really interesting dynamic that's set up, because in some ways, you represent the capital A art world. You're a part of a transactional, rhizomatic system that prioritizes possessing desired objects, but you resist that mandate. You engage the object as it is, and photograph it. There's no value assigned to it, other than the object is the locus for interacting with others.

Lucas: Oh no, absolutely not. And part of that, to me, is I'm very interested in producing work that anyone can understand, not that alienates or intimidates viewers. I want a person to think, “Oh, I can see myself in this” when they see my work. I’ve encountered people who say that they don’t have any sentimental objects, but overall, a lot of people do. Many people identify with that, or even see things that prompt the thought, "This reminds me of a thing that my grandmother had or I had in my childhood," or whatever it is.

© Kija Lucas. Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, Drawer #1, Archival pigment print, 17x26" 2015-2018

Seikaly: Is it hard to resist ascribing meaning to the assembled images as you work with them?

Lucas: I would like to say no, but that would be a lie. No museum or archive is objective. I do my best to feign objectivity. I don’t make choices of where to put things by an attachment or feeling about an object, or the interaction with the person who owned it, or the way it was photographed, or how the participant described their own attachment to it.

I don’t want participants to bring in the coolest thing they own. That is not important to me. This is why I choose to arrange them in the way that I do, but I don’t think I can truthfully tell you that there isn’t any sort of subjectivity in the process. I can, however, lie to myself and do my best to be objective.

© Kija Lucas. Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, Shelf # 4, Archival pigment print, 17x26" 2015-2019

Seikaly: This project continues to reveal itself beyond the immediacy of the images. I think that’s part of the nature of doing work that is broadly defined as archival. Some nuance reveals itself with every looking experience.

Lucas: Yeah, I think... I will also say that it unravels itself to me in the same way. In the beginning, I was making these pictures and collecting stories, and like, "I don't know what I'm gonna do with this or how it's gonna look." And it turned into this thing where I was like, "Oh, it's gonna be a museum, but it's not gonna be a traditional museum with a capital M." But I want it to be something that is accessible to a wide range of people, as participants and as viewers. I want people to tell the stories about their lives and their joy and their loss, and all of that stuff.

Seikaly: Absolutely. So, you staged more than one installation of this in 2020, a year that will be forever associated with a global pandemic. Have you felt comfortable engaging with people, given the potential for exposure?

Lucas: Yes.

Installation photo © Deirdre Visser

Seikaly: And in that time, have you worked with people who are bringing in objects that are related to COVID deaths?

Lucas: None of it was related to COVID deaths that I know of. However, I photographed objects inside early in the pandemic - at Montalvo Art Center - without many regulations. When the pandemic shuttered the exhibition, it lived there for a while. And then over the summer, several people brought objects to my home. They met me outside, and then I went upstairs to photograph the object and then bring it back down. I photographed several people’s objects when the exhibition was installed at California Institute of Integral Studies. So, I haven't photographed anyone's objects that are related to COVID deaths specifically, however, a lot of the objects that I have photographed represent loss. And not only with death, but other kinds of loss: heartbreak or loss felt over a lifetime.

Seikaly: It’s a perpetual experience.

Lucas: I've thought a lot about announcing a COVID-specific call, like people photograph the objects and send it to me. But, I find that meeting with people is a very important part of this work. Storytelling is a big part of this, whether the person speaks out loud or writes most of it down. It’s important that the person is present.