© Qualeasha Wood

The multidisciplinary artist combines textiles and digital media to create new perspectives on Black femininity.

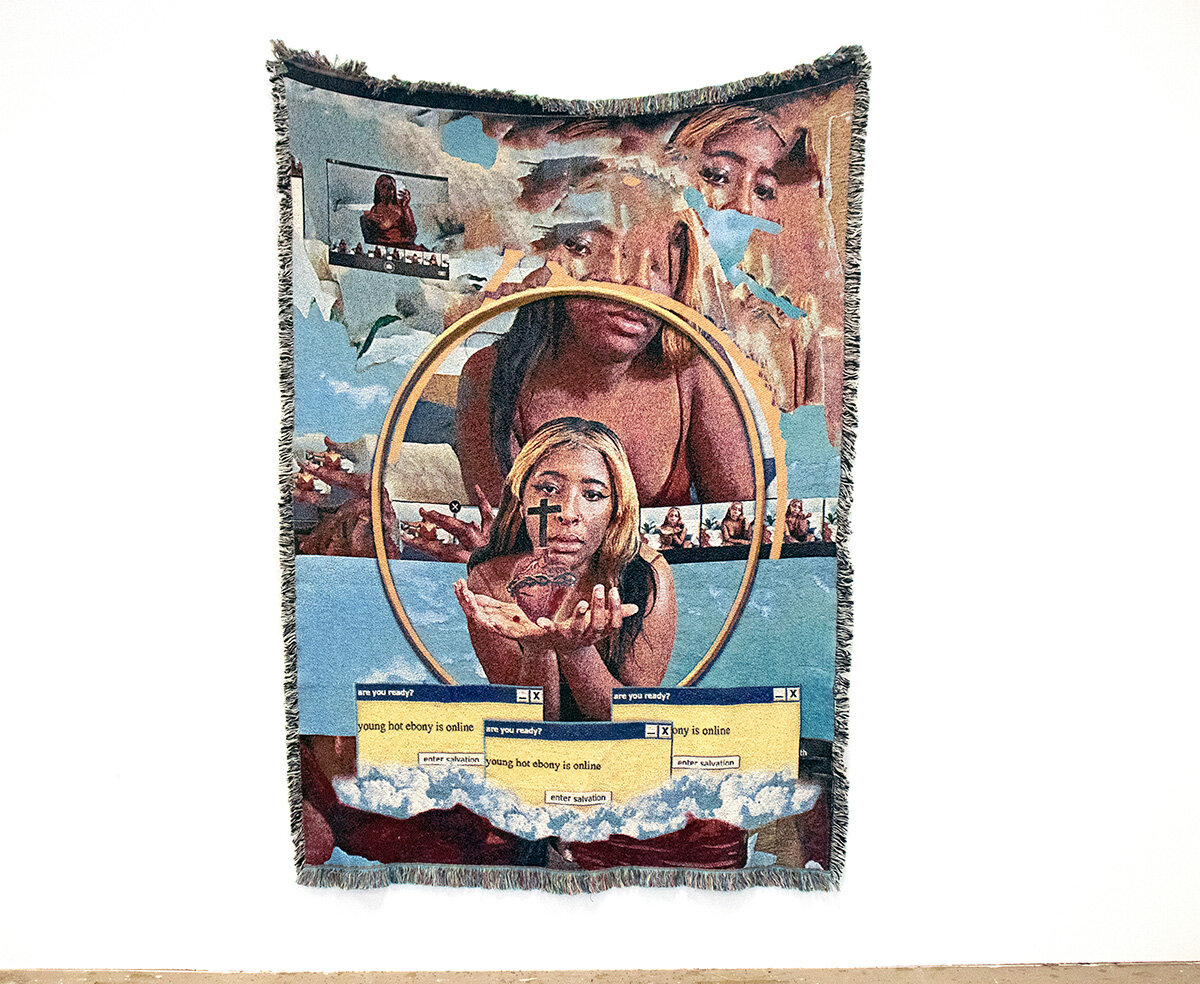

Have you read the latest issue of Art in America? Deftly assembled by guest editor Antwaun Sargent, “New Talent 2021” is bursting with writing by authors including Jasmine Sanders and Emmanuel Iduma and work by emerging artists Justin Allen, Miles Greenberg, and Tourmaline. I haven’t absorbed all of that rich content yet, but I have spent time talking with Qualeasha Wood, whose genre-bending tapestry Black Madonna-Whore Complex (2021) graces the cover.

Currently Detroit-based, Wood originally thought to pursue a military career, following the example set by her Air Force-veteran parents. That all changed after Wood enrolled in a high school art class on a whim. The experience clarified for her that art-making could be the physical and psychological space to explore Black femininity, and the joys and traumas inherent to that experience.

We met during a virtual portfolio review organized by Shanna Merola for Cranbrook Academy of Art MFA candidates in mid-2020. We reconnected to discuss image, symbolic language, and engaging the art world on her own, often controversial terms.

Roula Seikaly in conversation with Qualeasha Wood

Copy of Black Madonna-Whore Complex, 2021 © Qualeasha Wood

Roula Seikaly: What are the themes, ideas or problems that motivate your creative practice?

Qualeasha Wood: I definitely think if I had to name all the themes kind of in no particular order, I think a lot about gender, sexuality, race and religion primarily.

To encompass all that, I think the question has always been for me autonomy and accessibility, or lack thereof. From a very young age, I've been obsessed with what it means to have autonomy. I think we're born into this series and system of all these problems. You inherit your family's trauma, you inherit their issues, their class, race, all those things are inherited, and you learn to live and grow up with all of that. I have been trying to figure out who I am, or who I can be outside of those things.

And I think it's hard, or felt hard, to find a presentation for that. And so I spent a lot of time finding that, and I found that weirdly enough in video games, which is why I think my practice now is so digital in certain aspects. I’m heavily inspired by the digital. It was like playing the Sims when I was younger, and assuming this God-like position of, "I control these people. I've built these universes." And I think that's what inspired me to start thinking differently of how I can do this thing regardless of what's around me.

It's funny that I came to that realization through a different form of technology rather than through art itself, because I actually didn't find art that inspiring growing up, personally, until maybe high school and maybe my first few years of undergrad. Growing up I just kind of really didn't like art at all.

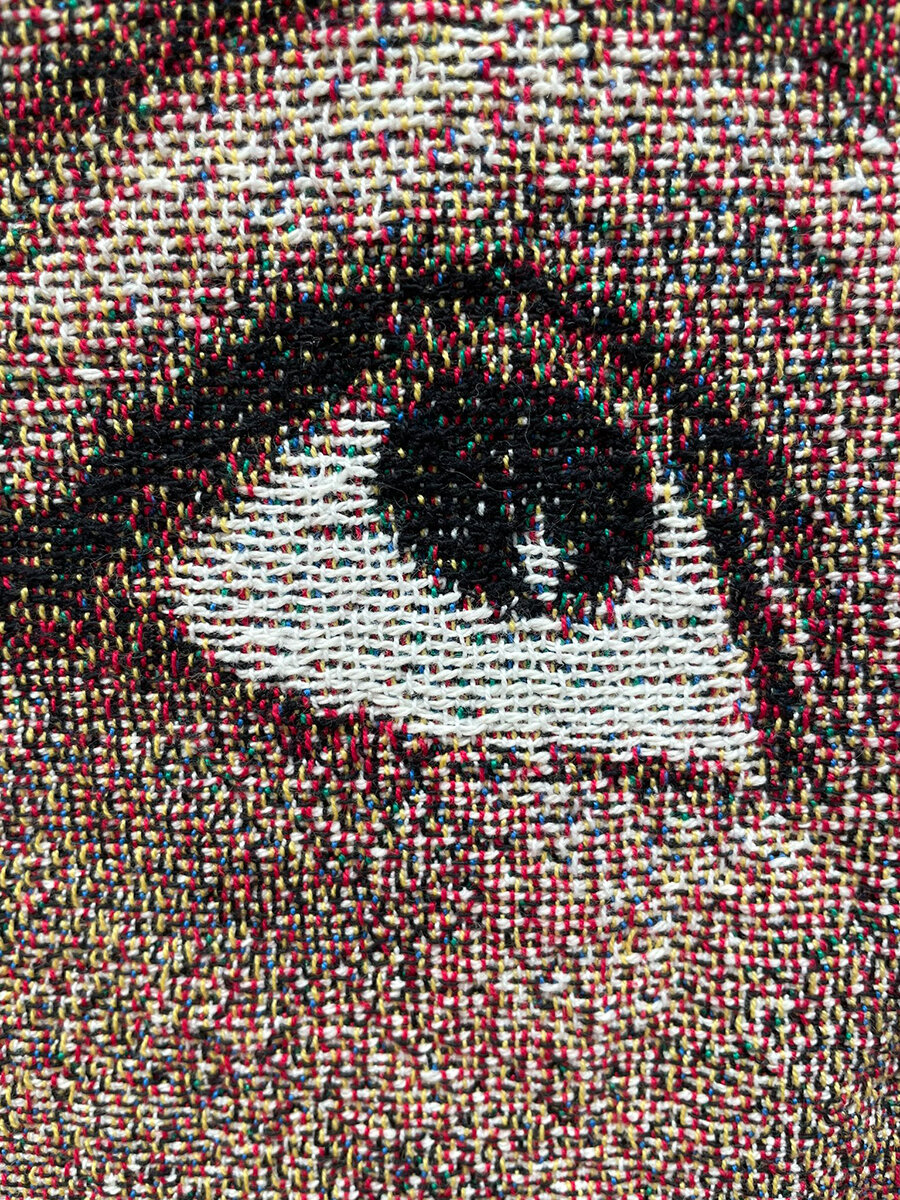

See God in the Mirror, 2019 © Qualeasha Wood

Seikaly: You earned your BFA at RISD. Given what you just said about not liking art when you were younger, could you talk about why you attended an art school? Was that part of exploring autonomy?

Wood: How that happened is actually really funny. I think in general, I went to art school to prove a point, which is that I can fill a gap I think is missing from myself, and then hopefully that fills that gap for other people. For most of my life, I had no plans for going to art school. Both my parents are military veterans, so I actually was ready to go into the Air Force. I took art throughout elementary and middle school, whatever. In high school, I didn't take art at all until my junior year when I dropped a class and the only class I could fill it with was art.

And it ended up just like, "Wow, this is so great." But I spent three and a half years in front of my Junior ROTC program, running the program as a student cadet lieutenant. So, I was very invested in that, very much thought I would apply to the Air Force Academy. And then I took art and it clicked. I actually applied to RISD after the deadline.

At RISD, I had a professor who was really problematic. Someone telling me I couldn't make art about race was just so insane to me, and something I had never experienced before. And I kinda was just like, "Who are you to tell me what I can and can't talk about?" And from that moment forward, I just kind of was like, "I'm gonna do it." I heard all these things, different things about racism, and things that happen to people that I never really had to experience. For someone to say, "Nobody wants to hear about this and that," made me think like, "Well, I have this power to make you uncomfortable."

That happened a lot, where I was just being authentic, trying to explore myself, and it had this effect on other people, which I thought was both funny and exciting. I started realizing the impact I was having with my community, on my friends, on people I didn't even know. Everybody was so obsessed with what I was making, what I was gonna say on social media in regards to different political movements and things like that, and I was just like, "All of you are treating me like I'm a God or something." And then, it clicked.

Fore The Day You Die You Gon Touch The Sky. 2021 © Qualeasha-Wood

Seikaly: I'm thinking about the tapestry work as you talk about feeling God-like, and all the external feedback or reinforcement you received. You situate yourself and your image among High Renaissance symbols and symbolic language, potent forms that drive the western art history. Can you describe inserting yourself in such a visually-religiously-historically loaded context?

Wood: Yeah. I definitely think of my relationship to symbolism in terms of religion, Christianity overall but Catholicism specifically. And that mainly just comes from growing up in a Christian family, and having Catholic friends. I never really distinguished the differences between the two, outside of what goes on in church. To me, they all feel like the same thing.

When making the work I just was like, "Okay, what does the stereotype of religion look like, and what do we associate with religious paintings?” And so having a print-making background, I think everything is always so dated and so back to the Renaissance and about what's useful. So, I found myself going to the RISD Museum and other museums and going through that period of art and paintings, not really necessarily caring about who made the painting. I'd just take a photo of what compositions looked like, and they were always the most dramatic painting, right?

The color palettes - a lot of red, lots of earth tones, lots of blue - and symbols including the cross and the Bible and how those drive the dramatic narrative in these paintings. I’m thinking about how those symbols come together with the contemporary symbolic language that is emojis. I'm trying to mix these historical references with these new relatable ones. For me, it all came down to aesthetics, and making a believable world for the work to exist in. I never really wanted it to come down to fantasy.

Test of Faith, 2019 © Qualeasha Wood

Seikaly: Yeah, that was one of the first thoughts I had, was about contemporary language and symbolism of emojis and how they are used in so many combinations to convey mood, emotion, and ideas. Thankfully, there doesn't seem to be a written code of rules, so to speak, as to how they're used. Language should be open to that. I’m marveling at how you use and contrast them with such reverently observed Christian symbols. I love that you are crafting your own language in these images, and how you insert yourself so unapologetically. Is that something you've thought about?

Wood: I do too, I honestly... Again coming from a printmaking background and what I was making before I started making tapestries, I think I was processing a lot of trauma that I didn't even realize I had until like I started taking all these certain classes in undergrad, I was like, "Damn. This thing happened, that thing happened." And people would always be like, "Oh my God, I feel so bad for you. This is so sad, blah blah blah," you know like that whole trauma-porn thing, and I hated that so much. I also love getting a reaction, but I never want a reaction of sympathy or pity. Usually, you have to piss somebody off to do the right thing. At least, that's how I feel.

When I started making the work, before it came to this final manifestation of tapestries, I made Self Control. Every day I posted a selfie of myself, turning it into some weird digital art college, and then wrote basically like a "dear diary" type caption, and how I was fed up with this, or how this was happening. And then I sold that book for almost $100 each. And in thinking about that, people were just so mad at me, and like people were arguing with me in the comments, and they were like, "You're so full of yourself, you're so into yourself." And I was like, "Well, why can't I be?" And then it's all about the former representation if you have White male painters who do self-portraits and we're like, that's not narcissism, that's just a reflection of time, you know?

Installation view

Seikaly: It seems to me that you are trying to address your identity, the religious tradition that you both embrace and critique. That’s challenging enough as a private endeavor, and then you put it out into the world on the Internet, understanding that you are gonna get all kinds of pushback from people. The flip side is that there are also gonna be people who see that, and really respond to it. So, the work is doing double duty in some ways.

Wood: Yeah, and I think that's been the most rewarding thing, 'cause I've definitely had a lot of backlash. I don't even know the extent that my parents know, but I've received death threats for my work. I received all types of threats for my work, especially when Trump was elected in...

Seikaly: Oh my God, Qualeasha.

Wood: Yeah, in 2016, when I wasn't even really focusing on that work yet. But when that happened and I was working on that selfie project and I had all these captions and things like that … I got doxxed, my images were shared all over Facebook.

No Church in the Wild, 2019. © Qualeasha Wood

Seikaly: That’s deeply upsetting.

Wood: You can Google my name and still see some things that people said about me. I can't get them removed from the Internet: personal stuff on really deep-web racist websites. And then when I started making the tapestries, it got worse. I'd get anonymous messages, sometimes on Twitter from burner accounts with people saying they love my work, then there's also people being like, "You need to die, this is awful."

I think, for a lot of people, that would really stress them out and scare them. And I think it did the first time it happened. Now I'm kind of like, "Okay, whatever." It's what I expect, making the work I make. I think about the people who have actually contacted me to say what the work means to them, or what it does for them, if it changes how they feel about themselves or how they experience the world, or how they even relate to art. It’s so worth it, like the rest really doesn't matter. Even though I'm 24 and I've only been making art for a short amount of time in the grand scheme of things, I feel I'm already accomplishing what I set out to do, which is to make space and change conversations.

Qualeasha Wood’s work on the May/June 2021 cover of Art in America.

Seikaly: Yeah, absolutely. That leads me to the Art in America New Talent issue and your work on the cover, and just how exciting that is. Congratulations!

Wood Thank you!

Seikaly: After you announced that, I read some of the interviews you've conducted between 2017 and now, just to be fully prepared for our conversation. The interview you did with Osun Taylor for Bluestockings Magazine is a brilliant exchange. You describe your youth in terms of meeting others' expectations like it's a performance. “Not Black enough,” not girly enough: these are two critiques that you heard often and that you respond to in your work. Now that you're on the verge of breaking big in the market-driven art world. I'm wondering if that performance of self is on your mind? What does it mean to you to be a young Black queer female maker in this high-profile context?

Wood: I think I had a problem at that time, definitely having to be all these different people and have all these expectations, and I think I'm still really struggling to figure out what type of work am I allowed to make? What's gonna even sell? I think that was the biggest pressure, honestly, for a long time. "Do I have to sell out?" I was so worried for the longest time that I was either gonna spend my entire life being extremely angry or extremely cool with it. And now, I recognize these different roles that I am expected to play as a woman, as a Black and queer person. I kind of just lean into it and I realize it's all a tool for me.

I make a decision like, "Yeah, if you wanna know about me as an artist and you wanna follow my work, there is no knowing about me as an artist without knowing about me as a person." I refuse to let anyone see my art and not have to see me at the same time. That’s really important for me.

When I started making the tapestries and I put on the outfit that I have designated for it, I felt like I was stepping into a persona. And I used to spend a long time getting myself into that space through intense rituals of, "Okay, I'm playing this music. I'm drinking this wine. I have this exact set-up in my space." I felt like I was literally putting out a performance and to make all these identities merge or perform. What would Madonna do? What would Jesus do? I was thinking all these things. For the Canada Gallery tapestry, the one that is in Art in America, I recorded those in my bed on a webcam. I’m thinking about desire and sexual vulnerability, and how much do I actually need to perform?" I’m thinking about what performance actually looks like versus what is authentic in my life and experience.

My gallerist Kendra (of Gallery Kendra Jayne Patrick) and I were talking about this year, this moment in time where Black women especially are on top of everything. In 10 years we'll be like, "Whoa, that happened," and people will be talking about it as this weird moment that happened in the midst of a global pandemic. But it's odd for sure, but it's really exciting.

Cult Following, 2019. © Qualeasha Wood

Seikaly: My hope is that it's not just a moment. I hope it’s sustained. There is so much work that white people, white-passing people like myself have to do. Thinking of you specifically as an individual and of so many Black, Brown and Indigenous makers, hoping that you don’t end up feeling like your work is commoditized. I hope you have the resources at hand and people to support you as you enter the art market machine.

Wood: Yeah. The best part about working with Kendra has been working with a Black woman who’s a little older than me. She's not that much older than me. But it's like having a big sister, like an auntie in a way. The first thing she says to me before we even talked about our presentation, way early in the show together, she was like, "You're gonna have a lot of people that are just gonna swoop in and flatter you and try to use you." And she was like, "You need to be super careful about that." And I swear, it was right after she that it happened. I was just so happy and flattered that somebody wanted to own something I made.

I was like, "Oh, if we could sell for this amount of money, this will pay my bills, I'm happy to do it." And then you look back and you're like, "Oh, this person used me." And they did this shitty thing, and that shitty thing, and now some of my best work is in the hands of people that I don't even talk to or care about. And it definitely sucked but I think it taught me a lesson of yeah, about being a commodity. I understand that my relationship to a lot of people and especially to whiteness is as an object. Afro-pessimism teaches that; being a derelict object. And I've had to make my peace with being commodified. I have decided that I'm doing it on my own terms. I used to say to my friends all the time, "No one's gonna pick me out, I'm gonna pick myself."

I'm the biggest advocate for people not getting MFAs, even though I'm getting one. But I would have never pursued the MFA if it wasn't free. And I wanna get my MFA so personally I can tell people not get their MFAs. If I have this free resource, I'm gonna use it. Everyone I know who is like, "Should I go to grad school?" I'm like, "Only if it's free."

Artists and capitalism go hand-in-hand. Until we overthrow all the other systems - academia, commercial galleries and museums, auction houses, whomever profits off of what artists make - nothing will change. So, I think we have to change how we get money, who we get money with, who we show with, who we sell to, all of it.

Seikaly: Absolutely. I love how strategically you think about this, and how undermining the massive, unrelenting, unfriendly systems is central to your thinking.

Wood: Yeah, it's been a pleasure to do that.

The Itis. © Qualeasha Wood

Seikaly: I want to switch directions and ask about the tufted pieces. They’re so different from the image and language-based tapestries. To me they suggest caricature, and cartoons or comic strips/comic books as source material. Is that accurate?

Wood: Yeah, so with the tuftings, I definitely have looked at a couple of different things, and it's kind of in a rabbit hole of how I got here.

I was making all these tapestries and I kinda wanted a break, and I wanted to do something else with my hands. And I went home to New Jersey and my parents have photos of everything, and I saw these photos of my childhood bedroom, and in one of the photos was a Baby Looney Tunes rug hung on the wall. And I was like, "This is where I got this from. My parents would put anything that they think looks nice on the wall." Then I started thinking, "Oh, can I use this? How do you even make a rug like this? Can I have a conversation about that?" I was like, "I've never seen anyone have a conversation about anything outside of really patterning, with rug making." So, I did some research, and got into it. I watched a lot of Tom and Jerry, older cartoons, Felix the Cat, but then I started getting into Steamboat Willie and Walt Disney and how racist he was.

I talked to a lot of my friends about cartoons and how I draw using digital formats, and they suggested I get into the racist history of cartoons. I also got into minstrel history, and the white gloves as a part of that. Also the relationship between minstrels and clowns, and I just was like, "Oh, my God," and it's still even today, Sonic the Hedgehog has white gloves. At this point in time now, it's about animation made easier. It's easier to animate hands when they're in the white glove, but before it just was this ode to racism, and this nostalgia. I was thinking about this figure that I use to represent myself, and how simple it is, and how simplistic representations of Black women are and have been.

© Qualeasha Wood

Wood (cont’d): I started watching all these cartoons, and then using the spacebar and freeze-framing everything, and looking for moments that I felt I just connected with. And then I started following all these Twitter accounts that post random screenshots from The Simpsons, Tom and Jerry, and Looney Tunes every day. I started deep diving and spending all my time watching cartoons because there was something about the animation and exaggeration, and the simplicity of a cartoon or a comic strip frame that really resonates with me, somebody who started drawing in a sense, through Microsoft Paint, just making these basic shapes and figures. That’s where this figure came from.

For a long time, I didn't know what the tuftings were doing. I thought honestly, it was gonna be a hobby for me. I didn't think anyone would like them, and I thought that everyone was gonna kinda hate them, 'cause I didn't know what they were doing. I hated them, and I should've known then they would do well because I didn't like them at first.

It really clicked with people. I think it was the first time in a while that I got 1000 likes on an Instagram post. And then I started getting all these emails from galleries I had a show with in the past that were like, "Can we see more of these tuftings? What are these?" And I was like, "Why do you all like these so much?" Inadvertently, I was inserting myself in these frames and in these compositions, through memory. I'm revisiting memories by watching these cartoons and finding a connection and then reinterpreting it. Oftentimes, there's a sense of playful childlikeness. They're such tactile objects people wanna touch, and they look like cartoons. I was like, "But then there's something wrong." Your brain just starts to unpack it.

Installation view

Seikaly: I look at them and immediately think of Kara Walker's work. There's something about not seeing her characters’ eyes. Because we can’t see their eyes, and they can’t see us, the violent or absurd action is somehow okay. One of the things about your work that really stands out is those big wide eyes. Looking at them, I pause and think “I shouldn't be looking at this.” I had that in-my-gut-feeling, "Oh, I shouldn't be seeing or watching this." It interrupted the spectatorial gaze.

Wood: I think the tuftings are deceptive in that way. You're invited in. I think for the most part, they're in intimate spaces. You're looking in, and it feels like you're in that space, or you're right outside of it. And then, you realize that you don't actually wanna be there. But I'm obsessed with voyeurism as a concept. I feel like my whole life I've been on display; trying to be a good daughter; going to college, and getting called into administrative offices for my social media usage and pissing people off and not making the college look good as an RA; being policed for every action. After Dark, the piece with the girl crying and running away under that spotlight, is how I feel every single day. It’s about police brutality, about feeling called to speak and never be able to grieve in peace, my feelings like a public act at this point. And it’s a social media reference about being afraid to walk home alone at night.

I feel like there's a million eyes on me. Also, I want people to be unsure, to not know if the eyes were just for me, or the character in the work, but or for them. Funny enough, when I draw them, I draw out eyes on my little Photoshop thing, but a lot of times I just put the emoji.

A lot of people are angry about it. People have talked to me about how I'm setting the culture back by many, many years by making this work. Someone said, "I worry that you only make this work for White people, and that it's not having a good conversation about race and you're relying too heavily on stereotypes, and it's just not doing anything for anybody.”

He listed all these different Black women that I need to look at, that obviously I've seen. He listed every generic big name that we all know, and he just was just like, "Yeah, no, I just worry that this just looks racist.” I stopped him and said, "If the work makes you so uncomfortable, that is not my problem. Don't unpack that with me. It's only a racist depiction of a Black woman because of our historical context in the United States and what we've done to representation of Black bodies," I was like, "But that's not my doing. If I choose to reclaim and transform that, you have to deal with it, but I don't have to make you feel good about it."

Installation view and detail

Seikaly: How large are the tuftings? Do you work in a range?

Wood: The largest one that I just finished is 58 x 78, 80 inches.

Seikaly: Oh, that's really big!

Wood: I know. It's huge. And I was documenting while making it, and I had to build an 8 foot x 8 foot frame, which was ridiculous. I can take it apart. In an ideal world, I'd carry it, but then I measured the door frame, and the door frame is like seven feet, it just stops right here. But I learned a fun thing that I get to do with the tuftings that I don't get to do the other work: control the scale entirely. And also, I would never in a million years, cut into a tapestry.

Everyone's been asking me to do it, I refuse. Those are sacred objects, and everyone's like, "You're so scared to do, whatever, whatever." And I was like, "Yes, I don't wanna do it." I'm like, "I'm not scared, I just refuse." I spent a good amount of time trying to figure out the tapestries. But with the tuftings, it's all intuitive. The way that I cut some of them out of the frame, is a decision that never happens in my sketches.

Meekmill Dreams and Nightmares © Qualeasha Wood

Seikaly: This has just been such a pleasure. Thank you so much! One last question: you've just finished at Cranbrook. You're coming out of an upside-down year. What are you looking forward to in 2021, and the years that follow?

Wood There's so many things I wanna do. That's a hard question. I'm looking forward to seeing what I do now that I have unrestricted free time. I think the safety cushion of being in a grad program is that someone is always expecting you to produce something. I think Cranbrook's a little different because it's residency style in a way. I stopped feeling like I was making work for fatigue. I just made the work as I felt necessary. It’s now summer, and it's like, "What do I wanna make? And how long can I take to make it?" I put myself in these crazy positions where someone will tell me they want a tufting a month from now, and I'll wait until two weeks before, and that's when I'll make it. Instead of utilizing all that time.

I’ll think, "What does it mean to make work?” and then sit with it, and maybe no one ever sees it, and then I make something else and start to catalog my own work and just have all these things? I never wanna keep my own work in my house. I want it to always be somewhere else, but I know now that that's gonna be the reality of, I'm gonna have to see these things every day. I'm looking forward to just having the space to live and explore the work in different ways, and have time for work, I think that's the thing I'm really looking for.

I'm also looking forward to not hearing anyone's feedback, which sounds strange, 'cause I think we all go to grad programs to hear feedback. That's what people want. I feel like at a certain point, when making the tuftings especially, I had everyone in my ear about what was working. I needed that, but it just started to get in my way at a certain point. Now, I'm interested in self-validation around the work, and no one else seeing it until I'm ready for it to be seen.