Bread (Cross), 2017. Archival Pigment Print. 24 x 30” © Eli Durst

Eli Durst’s ”The Community” hovers a haunting line between what is real, what is imagined, and what falls somewhere in between.

Photographers often consider themselves storytellers. Amongst many photographers of his generation, the work of Eli Durst proposes a new definition of narrative and the documentary photograph; one more sprawling and supple and interpretive without the self-imposed ethic of ‘objectivity’ without pious obligations to fact. The work slithers through loopholes of fact and fiction, and with disarming sleight of hand and stealth presence, accumulating evidence and masking visible purpose.

Looking at a photograph from The Community can feel as if walking into the wrong apartment, suspended in a social fabric without clear definition (nor even the certainty that one is still in the general present). The work disorients while seeming very, very familiar. Durst is a folklorist of our self-absorbed, flattened, culture; the eternal middle-brow.

Durst’s solo exhibition of The Community is on view at Foley Gallery through April 4th.

Stephen Frailey in conversation with Eli Durst

Animal Demonstration, 2017 11x14” Archival Pigment Print. © Eli Durst

Stephen Frailey: When the book ‘The Community’ was published last year, it seemed much of the response was in relation to the work as a sociological document, perhaps influenced, of course, by the emerging isolation of the pandemic. Considering the work now, I’m struck by its stubborn ambiguity. I’m reminded that photographs are more enigmatic than we often understand, and your work seems to exemplify photographs that are as unresolved, in media res, as their corresponding quantity of information. You have written about resisting interpretation, so I suspect that this contradiction of the photograph is of interest?

Eli Durst: It definitely is and I think you’ve hit upon one of the interesting paradoxes of photography. In order to make work that feels universal, you’d think that you should make images more general but the inverse is actually true: relatability lies in specificity. It’s the details in an image that often make it feel real or authentic—that give it life. I have always loved the Diane Arbus quote “a photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.”

Photography is simultaneously an indexical document and a wild fiction. Making ‘The Community’, my aim was to create a fictional world out of our real one. The strangeness and ambiguity inherent in this translation is a big part of what animates the work.

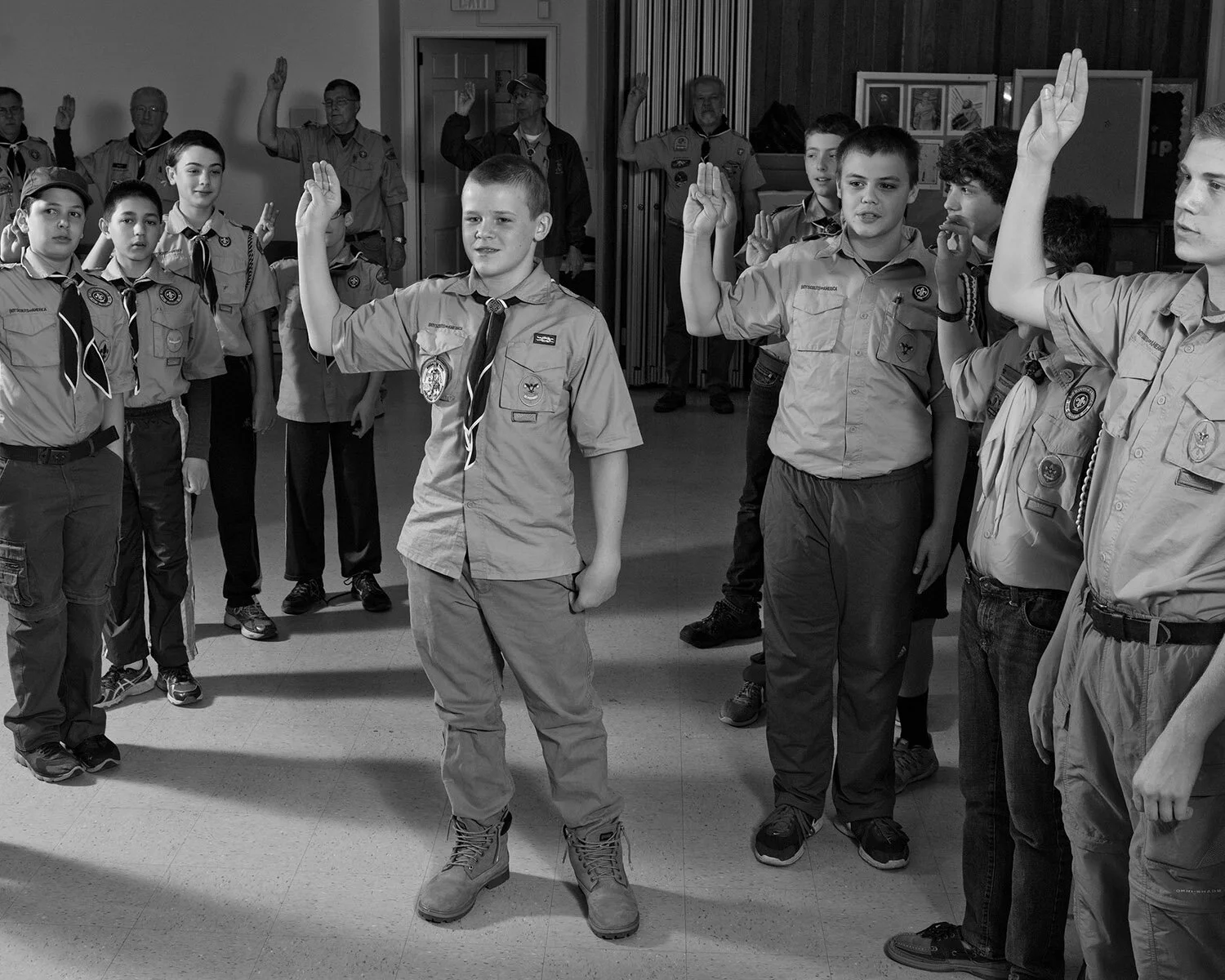

Boy Scout Salute, 2015 24x30” Archival Pigment Print. © Eli Durst

Frailey: I would say that the central concern of contemporary photography is to operate in different increments between fact and fiction, exploiting its reputation as evidence. What you propose “to create a fictional world out of a real one" is engaging, one could argue that the gatherings themselves are a form of fiction, of theater. Perhaps that performative aspect is important to the work, slipping between categories of experience….

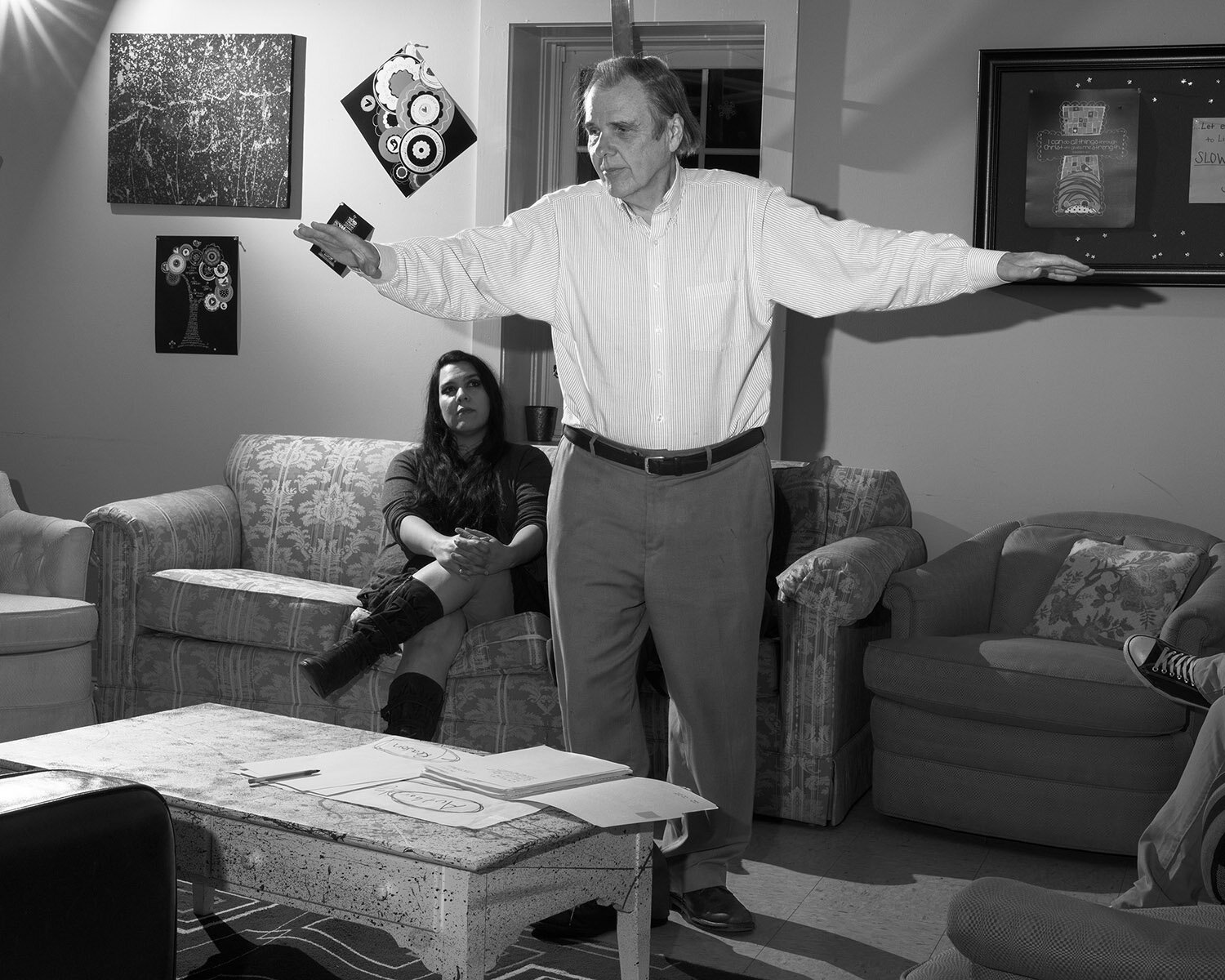

Durst: I’m very interested in performance. We’re all constantly performing—performing who we are and who we want to be. Several of the images in the book deal explicitly with the idea of performance in that they depict a community theater troupe; actors charged with the task of embodying another reality in a compelling way. But many of the other images deal with it implicitly.

Whether it’s Boy Scouts starting meetings with their pledge or a bible class opening with a prayer, formalized group activities all have ceremonial elements, rituals that imbue the experience with meaning. I’m fascinated by the idea of activities that are meant to enact some form of self-improvement or self-realization—and the challenge of photographing that. How do you represent interiority when photographs can only describe surfaces? It’s a bit of a conundrum.

Pile, 2017. 24x30” Archival Pigment Print. © Eli Durst

Bruce Spinning, 2015. 24x30” Archival Pigment Print. © Eli Durst

Frailey: If I understand correctly, you have been working in black and white since ’Pinnacle Reality’? Black and white seems particularly appropriate for your thinking and it, I think, adds to the sense of the generic in ‘The Community’. Could you speak to your decision to work without color?

Durst: Thematically, I like how black and white both unifies these spaces and distances them from our reality. The photographs in ‘The Community’ were made across the US, mainly in Connecticut, New York, and Texas.

Removing the particularities of color helped make the work more consistent, creating the feeling that all these activities could be taking place in one strange and busy community center. I also appreciate how black and white helps separate the fictional world of the book from the real world in which I was photographing. Hopefully, it creates a sense of defamiliarization, allowing the viewer to see these spaces and groups with new eyes—to cast relatively mundane activities like corporate team-building exercises or Boy Scout meetings as important, modern rituals.

But, to be honest, deciding to switch from color to black and white was firstly a technical decision. Before making ‘The Community’, I very much thought of myself as a color photographer. I worked exclusively with large and medium format film, shooting outdoors in natural light. But at a certain point, I started to crave photographing indoors, I felt like there was just so much of the world I wasn’t seeing. I was especially interested in the activities that went on in church basements.

Formally, I really didn’t like the way the strobes that I was using mixed with the available light, which was mostly overhead fluorescent lighting. Putting the images in black and white was a way around this problem. And once I started thinking about the work in black and white, the project really found its voice.

Lamp, 2016. 11x14” Archival Pigment Print. © Eli Durst

Tamra and Eric, 2018. 11x14” Archival Pigment Print. © Eli Durst

Frailey: The black and white also somewhat suspends the narratives in an unspecific time; they do not entirely seem of the present. And then, also the relationship to small-town journalism—the gathering of local organizations as recorded in the weekly newspaper.

Durst: Absolutely. The photos aren't timeless but there's definitely a sense of temporal confusion. It's also a reflection of how little these spaces have changed over the past couple of decades.

I think the connection to documentary photography or “small-town journalism” is an interesting one. I'm definitely not a photojournalist or documentary photographer, but I'm interested in the language of documentary and its close relationship to the idea of truth or reality—its authority or its "reputation as evidence" as you said earlier.

Mask, 2018. 24x30” Archival Pigment Print. © Eli Durst

Frailey: Lastly, I wanted to ask about what I sense as the isolation of the figures—perhaps a branch of the ambiguity that we began with—that despite an effort at community they often seem essentially solitary. And I think your way of working, in its objectivity, is reserved, deliberately. Both combine to create an emotional reticence that is very subtle and detached. Does this seem accurate?

Durst: When I'm making work—or evaluating it after shooting—I think about the idea of absorption—people completely lost in what they're doing, oblivious to the camera. I think the emotions that people project onto this absorption can vary, whether it's concentration, meditation, loneliness, solitude, etc. I think it speaks to the idea that you reference that, in a deep sense, we are all alone; we are all stuck in our own head, stuck with our own thoughts and insecurities and fears and desires.

And I think this impossibility or futility is connected to the photographic pursuit as well—the idea that, despite their best attempts to transcend or dig or puncture, photographs only see the surface. And this limitation is actually a strength.