© Granville Carroll

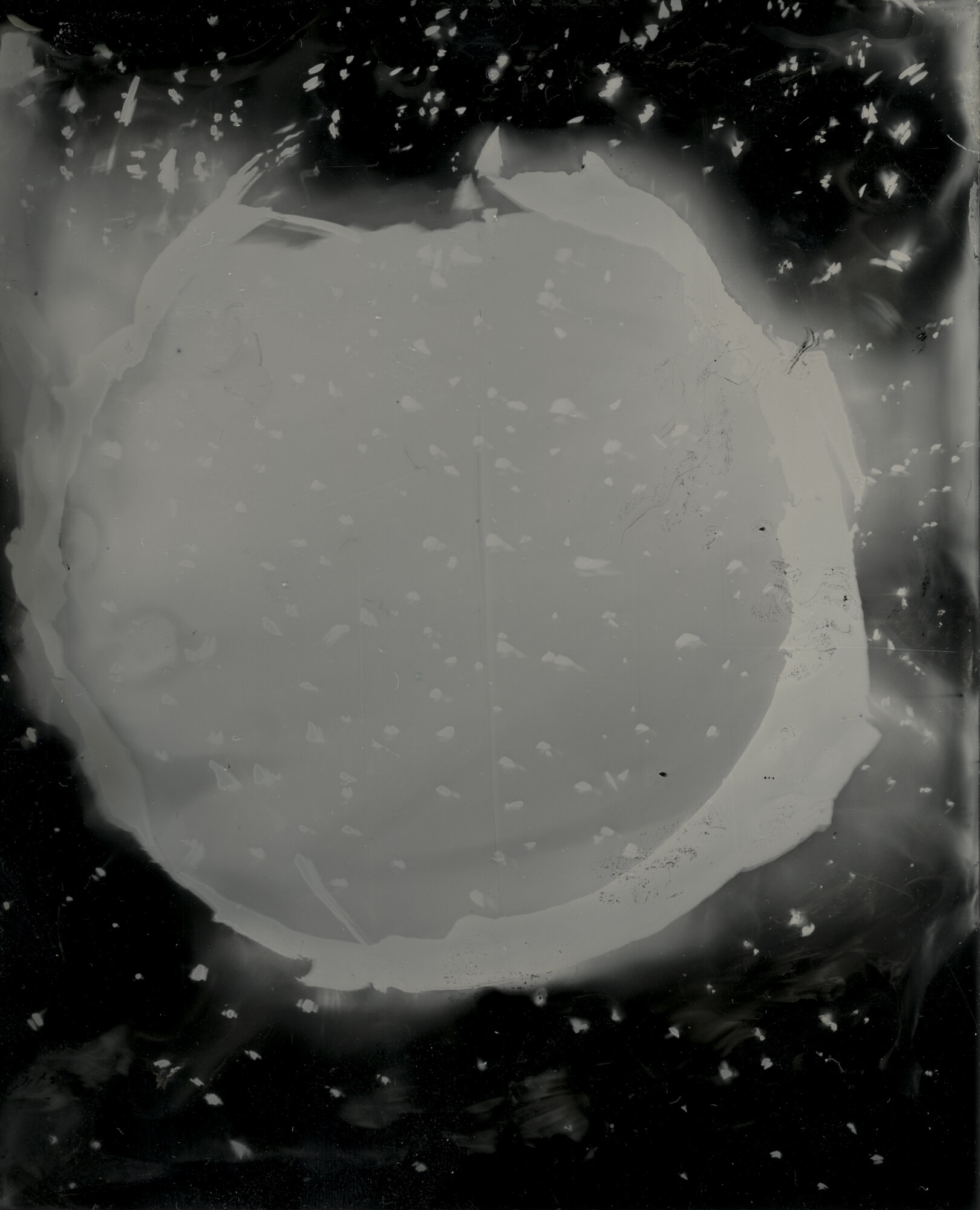

In his new series Cosmotypes, Granville Carroll uses a cameraless photographic process as a metaphor for "reclaiming power from nothingness."

As humans often do, Granville Carroll frequently ponders the origins of the universe. “I imagine the power needed,” he writes, “to make something out of nothing.”

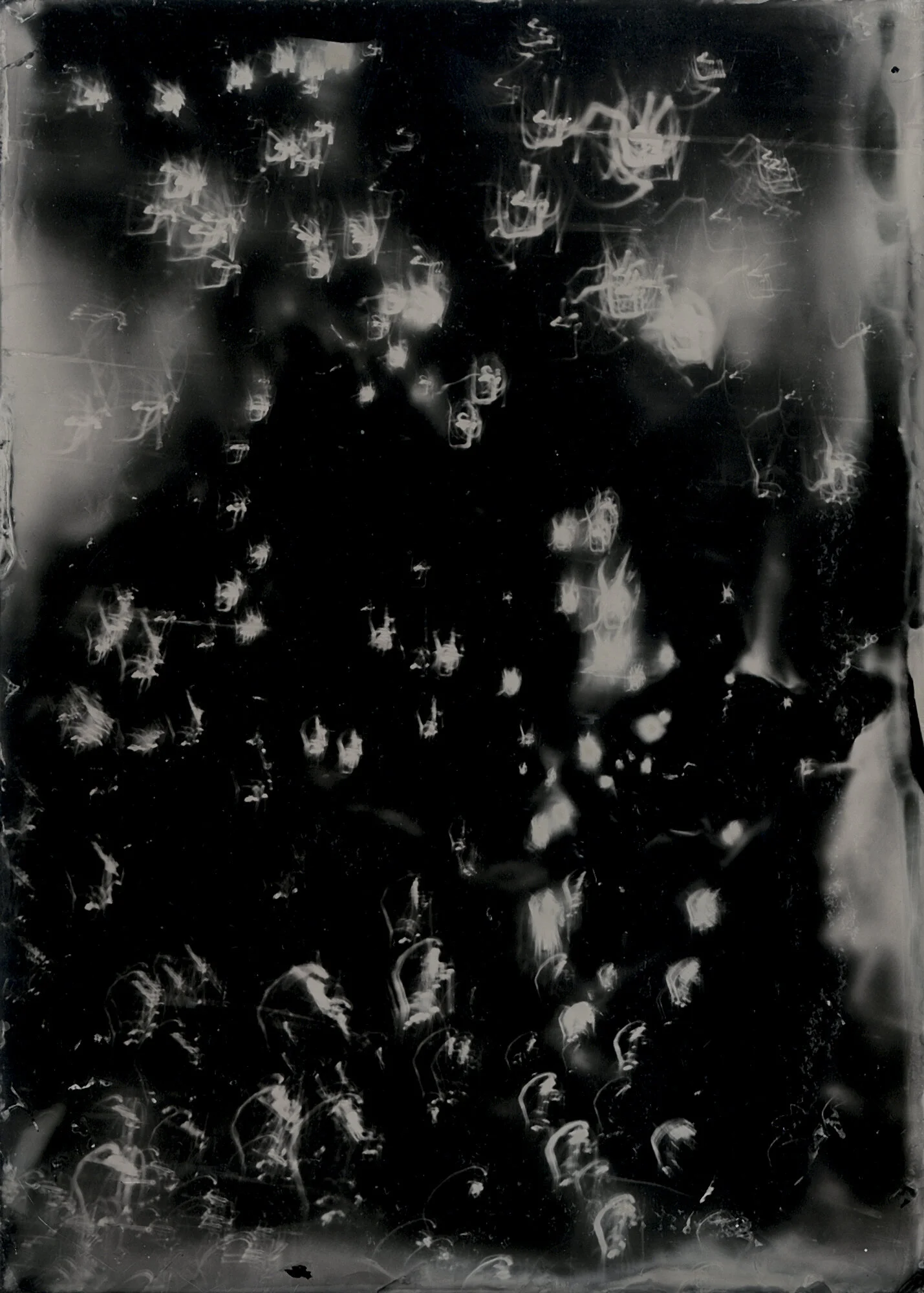

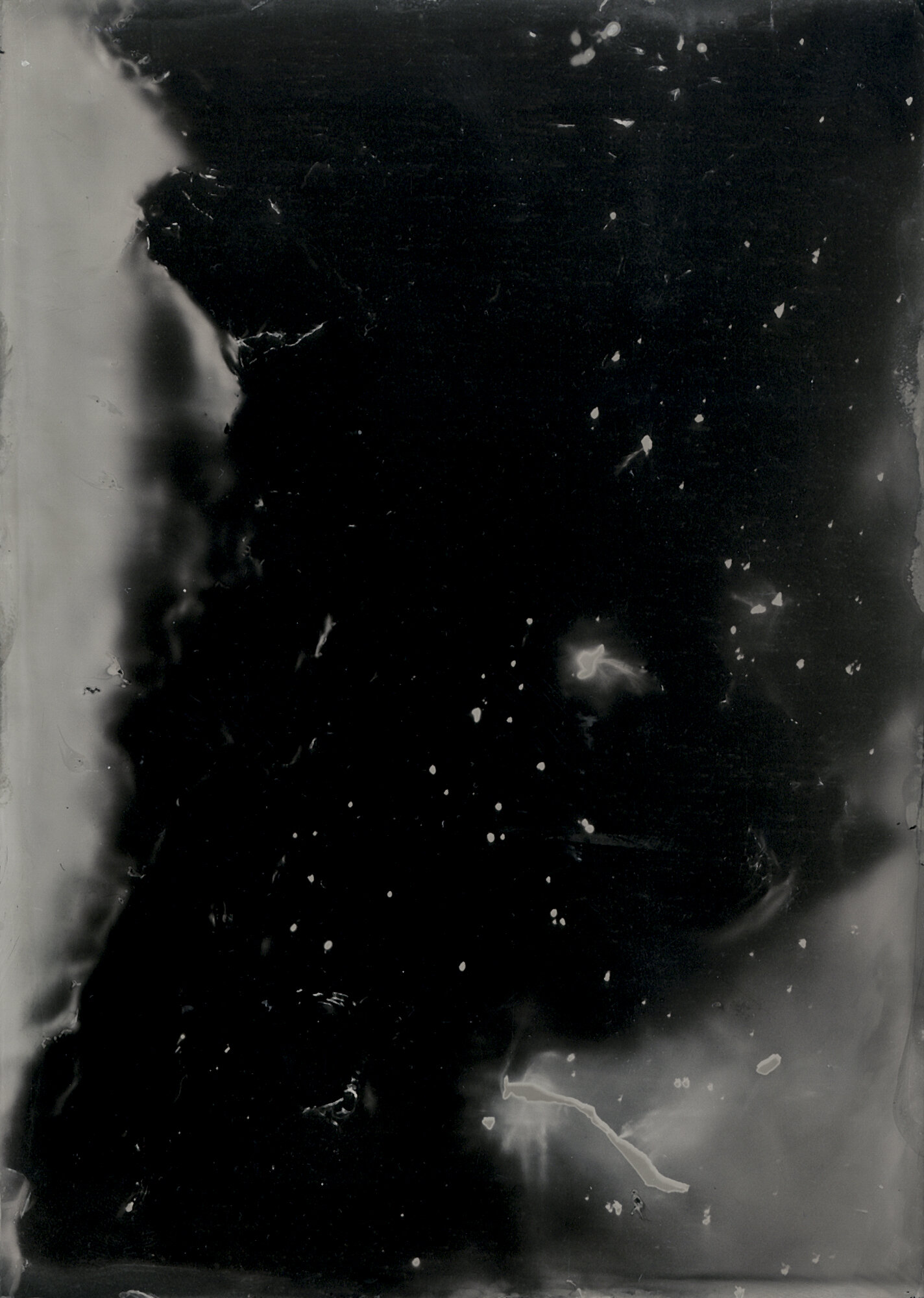

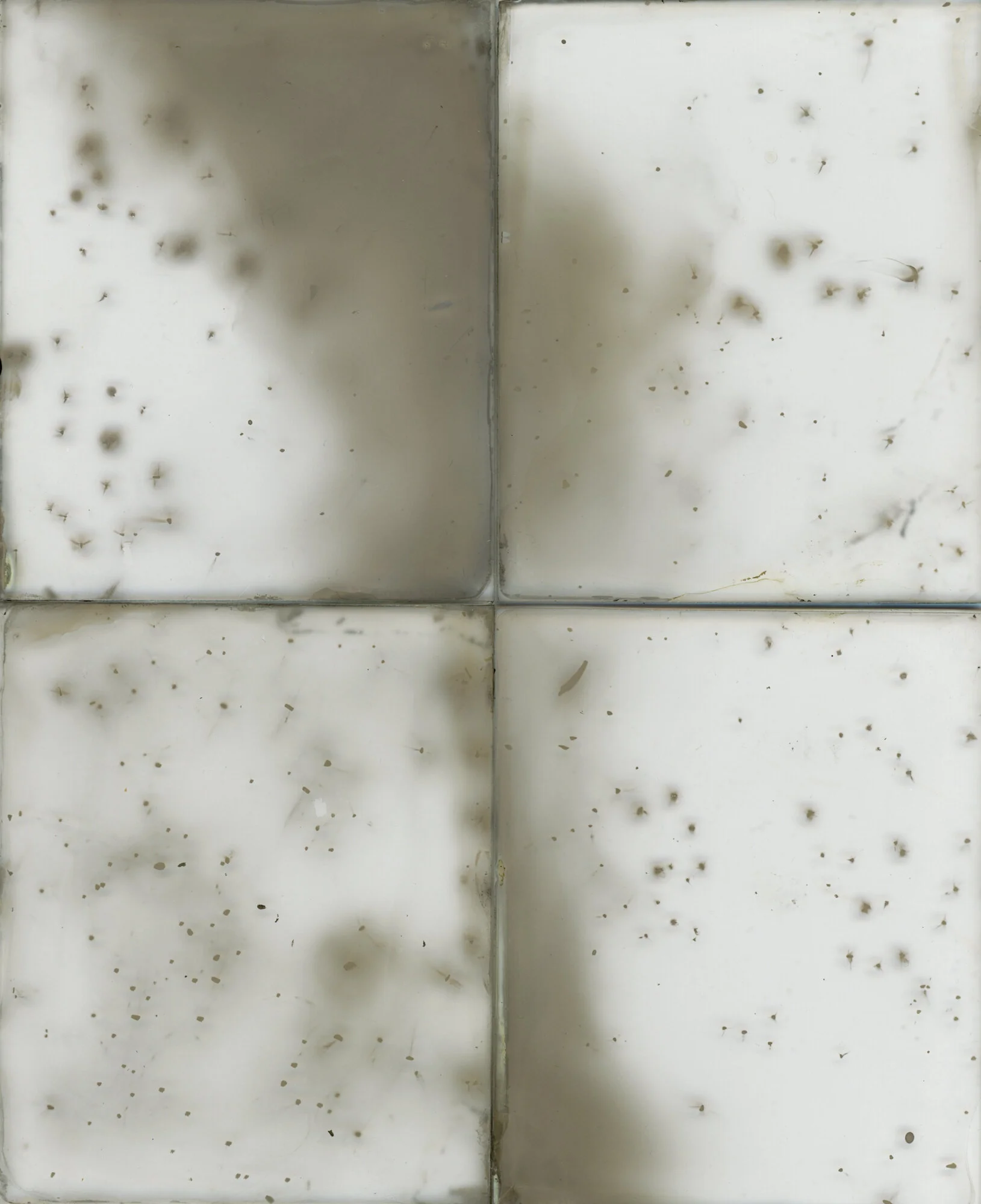

Carroll makes collodion plates on surfaces including glass, metal, and acrylic to mirror the creation of the cosmos. These "Cosmotypes" – dark, abstract, and prone to technical chance – reflect the mystery of what lies above and beyond and what might have come before it. For Carroll, these cameraless images are not just creation story meditations, but ruminations on control, oppositional forces, and his own cultural, spiritual, and personal journey. “I set my gaze,” writes Carroll, “on the expanse of space, marveling at the vibratory dance of light and darkness.”

A longtime fan of Carroll’s work, I caught wind of Cosmotypes in December 2020 when he shared an early image from the series on Instagram and had to learn more. A few months later, we connected to discuss its present and historic implications and the flourishing expanse of cosmological photography.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Granville Carroll

© Granville Carroll

Jon Feinstein: This is one of the most exciting projects for me over the past few months. I remember when you first shared one on Instagram, being familiar with your past work, I knew in my gut that I was going to continue to be intrigued by it, and that it was going to amount to a substantial, consistent, powerful series.

Granville Carroll: Thank you for the kind words, I am deeply humbled and grateful for such a response to the work! At the core of my practice is the existential questions we so often ask. Everything I make is influenced by these concepts and questions.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: I understand that when you first started making these images, it was for an assignment in a collodion class you were taking. At what point did you realize "wow - these aren't just cool alt-process experiments, they're existential "Cosmotypes..."?

Carroll: The first class I took was in grad school with Willie Osterman. He told us in the beginning of the course that he wanted us to push the process beyond the usual portraits and still life images. Immediately I started thinking of ways I can challenge the limitations of the wet-plate process and create images that are new and refreshing and about how process relates to concept.

Once I learned the process and was able to work more independently that’s when the magic erupted. I was making this work at the same time I was working on my thesis (Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me), so I was already inspired to work with the cosmos, light, and darkness. A lot of the influences of my thesis research informed my decisions in making these collodion plates.

When I began creating the Cosmotypes I was photographing projections of NASA’s Hubble Telescope images on the wall. I got a few good images but ultimately the exposures became too long, and my plates dried, which led to no image during development. If I couldn’t make reproductions of the actual cosmos, I wondered how I might create my own.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: What happened from there?

I am constantly asking, “what happens if…?” so, I experimented with using charcoal, chalk, and water on my coated plates to mimic the stars. I got some interesting results but what I saw in my mind still had not manifested. My failures lead me to the conclusion to just use directed light to create my own cosmic universes.

It was upon seeing my first Cosmotype that prompted me to think this had more meaning than I initially gave it. I felt I had achieved a unique image, but more importantly, I created a cosmic world that had never existed before. I had a thought that became reality. That power to create from nothingness inspired me to take the project even further.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: While the title “Cosmotypes” might seem relatively straightforward, I’m interested in learning a bit more about your thinking on it… are there personal origins?

The name for the project, Cosmotypes comes from my friend Hugo Teixeira. We shared a studio in grad school and often shared new work and ideas with each other. When I showed him these images, he mentioned the name Cosmotypes, which I absolutely loved. The name encapsulated what I wanted the images to represent.

After we graduated, Hugo taught a wet-plate course at a local arts center which I had the pleasure of taking. In this class, I was inspired and influenced by Hugo to continue making these starry plates and experiment with the process more. Being familiar with the process allowed me the freedom to explore more conceptually since I wasn’t as focused on learning the technical aspects. Overall, I don’t think there was a single point when the project was realized. As with most things, it grew organically over time through various influences.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: You also mention in your statement that this work ties into your lifelong interest in the cosmos. Were you thinking about this at all when you made that first image or did those ideas and connections develop as the work progressed?

Carroll: I was definitely thinking of this as I made the first images. My thoughts were set upon the unknown which prompted me to investigate the relationship between the observable universe and the inner mind (memory, emotion, consciousness). I am constantly looking at my past and its influence on my selfhood and art practice. Since I can remember I have been asking where this universe comes from and what or who sits at the apex of creation.

As I developed the image, I would wait in anticipation to see the birth of cosmic universes unfold; my mind transported to the scene where thought crystallized into matter. I imagined the excitement and profound joy that must have been present at the moment the universe saw itself for the first time. I was thinking about the origins of the universe, which is also the origins of my existence.

The thought that I could perhaps see myself reflected in the cosmos excited me. A deep sense of connection moves through me as I create these cosmic worlds. I am reminded of childhood visions seeing myself immersed in a sea of stars unfolding into the fabric of space.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: Has making this work changed or expanded upon how you think about cosmology?

Carroll: Cosmology can be viewed through a lens of science, philosophy, or spirituality. From a scientific perspective, cosmology is the study of the universe’s origins and where it is going. I find that study to also reflect the search for, and rediscovery of, self.

I am reminded of the energy present at the conception of this universe and how it has transformed into what we know as reality. Cosmology is a way of understanding our individual selves while also learning about the collective meaning of humanity.

It presents more questions than answers. How do we evolve and develop based off the functions of the universe? Do we know enough to definitively say where it all began and what’s next? As we learn about its mechanical nature what will that do to the ideas presented through religious and philosophical thought?

There is only so much we can know because of the limitations of our current technology and position in space. Spirituality is argued from a dogmatic perspective. Philosophy is essentially asking “why?” with no end in sight. There are faults in everything, and I think individually they can only tell us so much. The union between these schools of thought can form new understanding and create possibilities. This project allows me to explore the intersection of these points which definitely expands how I experience and think about cosmology.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: Do you see this work being in dialog with Mikael Owunna’s work?

Carroll: I had the pleasure of meeting Mikael and discussing the implications of making artwork that doesn’t fit the traditions of the medium. There is power in telling stories that are not at the forefront of American culture. I see his work expanding the way we perceive ourselves and our relationship to the natural world. There is power in being a vessel for the cosmos and he encapsulates that beautifully in his Infinite Essence portraits. I think we are both asking, what does it look like to be the creator of that vessel and transmute pain into healing

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: I was also thinking about a tie-in with Jamie Robertson’s work (more conceptually than aesthetically.) What do you think?

Carroll: Both of these artists explore issues of representation which leads them to reclaiming power. I see that being in conversation with the work.

The connection with Jamie’s work is definitely more conceptual than aesthetic. My work is a rebellion against the Eurocentric way of perceiving the world and I think she is working with a similar frame of mind. Jamie’s approach to decolonize the way Black bodies are seen is confrontational, yet soft and poetic. In Jamie’s statement for Making Reference, she states, “I explore my perceived identity and question how I see myself versus how others see me”, reading this deeply affected me. I share this same sentiment. It is a question I constantly meditate on. I find it quite profound that our thoughts are so entwined. It is refreshing to see others pushing against destructive labels and asking some of the hard and possibly unanswerable questions.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: I believe you've described your work as afro-futurist in the past, and I'm wondering if you now see wider associations into African Cosmology (fluid time, etc) with this work?

Carroll: Afrofuturism is just a starting point for me. Lately, I have been drawn to the symbolic, cosmic, and spiritual influence of circles. The Cosmotypes are made up of tiny dots of light and represent endless possibilities. They point to cycles of creation and destruction. I’m definitely thinking about time’s endless and malleable nature.

I see time as a circle, which contracts and expands as we dive into the past and project into the future. In Yoruba cosmology the Calabash of Existence is a circle or sphere acting as a cosmological model that sets the hierarchy of the universe. The top half of the calabash is the heavenly realm where Olódùmarè (the supreme head of the cosmos) and the Orishas (deities) reside. The bottom is represented by the material world of the living. This model is based on the movement of the stars and cardinal directions. It connects the sacred to the secular. I am interested in this relationship in addition to the intersection of science and spirituality.

Additionally, I am interested in the Dogon people of Mali. It is believed they had ancient knowledge that Sirius is a multi-star system before it was confirmed by scientists. I am deeply interested in the idea that knowledge and wisdom transcend temporal boundaries. They believe that there is no separation between the conscious mind and the physical world. A concept I am very much intrigued by and inspired to make work from as well. I am interested in the concept of quantum mechanics and the transfer of information between particles, atoms, and molecules.

I am no scientist, and there is much to learn and understand, but I find the concepts of science influencing how I perceive the world and informing my creativity.

Feinstein: Does making this work change how you think of your larger practice?

Carroll: This work expands how I think about my larger practice in terms of the various ways I can investigate the ideas of origin stories, cosmology, and identity through various schools of thought.

Feinstein: What drew you to experiment with the collodion process?

Carroll: I have always had a love for 19th-century processes. My practice mainly involves digital technologies so I always take advantage of the times I can work with a new process. I was drawn to the materiality of wet-plate collodion. The collodion process doesn’t require paper to produce an image. I love the ability to use materials like glass, acrylic, and metal to render a photograph.

Working with 19th-century processes brings me closer to the elements of nature since they usually involve various compounds of rock, salts, and metals to create an image. I’m drawn to the basic alchemical elements (earth, water, fire, and air) and their symbolic and literal functions in creating these images. The process lends itself to a transformative experience conceptually, chemically, and spiritually.

Feinstein: Can you dig into the physical-chemical process of making these images?

Carroll: Making this work is quite a process. There are many volatile chemical ingredients that need to be measured accurately and properly mixed. To simplify, the process involves taking a plate of material (usually a glass or metal plate) and then coat it with a collodion solution (derived from cotton and mixed with various chemicals). The coated plate is then dipped into a silver nitrate bath and the chemical reaction between the collodion and the silver creates a light-sensitive surface.

To make the Cosmotypes, I begin by poking random tiny holes in foil. I then pour the collodion onto a plate, drain the excess from the surface, and submerge the plate into the silver bath for about 2-4 minutes. All of this is done in safelight conditions (a low-light environment). Once sensitized, I lightly place the foil on top and then use my phone’s flashlight to expose the image for a couple of seconds. There is no camera and no lens involved in this process. After I expose the plate, I get the joy of developing the image and watch the light and darkness appear before my eyes.

Feinstein. What's it like to make these, to go through the process from an emotional or cosmic perspective? I feel some level of spirituality in it…

Carroll: Creating these Cosmotypes is a meditative and transformative experience. There are many steps in the process so making one image is quite time-consuming. I find that the anticipation to see the final result builds and I have to be mindful to slow down. I have to learn to be still and present in that moment. Making these images is a proper lesson in mindfulness. Zen meditation teaches one to act with intent and to be aware of intuition. While working I try to achieve a balance between intent and intuition which prompts me to act with purpose and allow the process to unfold as it may.

It teaches me humility, to accept imperfection, and to find meaning where it didn’t exist before. It is like a spark that ignites a fire that illuminates the interconnected strings of reality. I imagine being an architect of reality as I build new universes with light. It is a gift and profound experience to make alongside the forces of creation. I often think about the various origin stories that tell of a force that spoke the world into existence.

The process to make these is similar in that my thoughts become reality. I immerse myself in these ideas to empower me to imagine new worlds. I experience a sense of gratitude for being able to witness and take part of this amazing experience. It is a rich emotional experience that brings me closer to life.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: If you're comfortable responding, I want to dig a bit a little deeper into where you are in all of this, and what's pushing you to make work about these existential issues. In your statement, you use the words "I take hold of the power of creation to conceive of my own cosmic universes." Can you expand on what compels you to create work about this sense of control?

Carroll: I connect to my sovereignty when I exercise my power to create. Our society tries to dictate who we are. Sometimes we feel the need to live up to the expectations of others and disregard our uniqueness. Race, gender, sexuality, social and economic status, and a slew of other constructs obscure selfhood. We lose our sovereignty when we blindly adopt these values without question. We give up our power and sense of control when we don’t take hold of our gift of life.

I make work about this sense of control because I feel we, as a society, have lost our way. I believe we have constructed a false sense of control through monetary, material, and social means. Our identity is built on weak constructs that cannot pass the test of time. We think because we “know” so much that we have a hold on our lives. The American cultural identity is not sustainable.

My work presents an alternative to the usual ways we construct our identity. I want people to understand the power of their mind and its ability to change their reality. The power and control that exists within the universe is present within us. We are a reflection of that power manifesting in physical and conscious form. True power is seeing yourself reflected in the cosmos. Where am I in all of this is exactly the question I am constantly asking. My answer, I don’t know exactly. It’s in this space of not knowing that compels me to make work about it. I surrender to the unknown.

Paradoxically, when I surrender to not knowing I feel more in control. Surrendering to the unknown expands the awareness and knowledge of self. It creates space for new information and experiences to be gathered. The mind becomes fortified in this act and the self begins to unfold its truths.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: We're living amidst two pandemics - one that's lasted a little over a year, and one that's lasted since the beginning of American history but has reached a heightened boiling point in 2020. If you're comfortable talking about that, I'm curious if you see that being in conversation with this work, much of which was made during this past year, along with its existential metaphors.

Carroll: Such a poignant topic in both respects. The horrors afflicted upon the Black community since the conception of this country is deafening. It hurts and it is painful. We are constantly holding death and destruction in our eyes. Making this work is reclaiming that power to create from nothingness. I make this work to honor the sacrifices and suffering my ancestors experienced to advance us. When I meditate on these thoughts, I find that the true strength was in the power of their mind. The imagination wields the power of change. Looking at the origin of the universe is simultaneously looking at my personal and collective history.

In respect to the health pandemic, I was constantly reminded of the fragility of life. Covid brought us to our knees. It shook every part of the globe causing us to recede into the spaces of our homes and psyche. We no longer had the control we thought we did. This lack of control over our lives caused fear and panic in many people.

Personally, I embraced the lack of control over external circumstances. Surrender is an important aspect of my artistic practice. This balance between control and lack of control is precisely what enables me to create in the ways that I do. These issues you describe may not be visually apparent in the final images you see, but they do inform my thought process in terms of power and control.

Feinstein: The parallels to power and control make so much sense here…

Carroll: Making these Cosmotypes imbues a sense of power in me. My goal is to remind people where they come from. Knowledge of self is important. In that remembrance, it is my hope that they can find their humanity and reclaim their power to shift their mind’s eye. This is the power and control I speak about wielding.

© Granville Carroll

Feinstein: To my understanding, this is the first series of yours that does not include some literal manifestation of the human form.

Carroll: The body has so much connected to it. When we see a literal manifestation of the human form, we begin judging it based off shape, size, color, etc. I was already dealing with issues of representation in my thesis and felt this work needed a space of its own. There is one plate, however, that shows the human form. I wanted to see what the human form would look like completely made out of light. It is actually one of my favorites in the series. It represents the body as a vessel for light and darkness to coalesce. I made the remaining Cosmotypes to find liberation outside of the body.

I wanted the freedom to feel existence in its totality without the heaviness and confines of society and culture. I wanted to see the body dissolved into spaces of darkness and points of light. These images were made to experience the idea of being and what that may look like. What is existence without form? Is it energy, is it the divine? These images reflect this act of questioning.

I see these images functioning as planes exhibiting the interplay of light and darkness. Light interacts with us and yet we cannot hold it in our hands. Darkness is experienced only in the absence of light. These forces exist in a state of presence and absence. This project seeks to make tangible the ethereal qualities of consciousness through the construction of unique and individual cosmic universes that are a reflection of all of us.