“Las Sirenas” september 2020. In memory of Cristina who passed of covid-19 in May 2020, Cypress Atlas poses, recreating the 1984 Sleep It Off album cover by Jean-Paul Goude. set assistance by Morgan Landry.

© a.r. havel

New Orleans-based photographer and set-designer a.r. havel’s work is a kitsch and quarantine-soaked memoir to teenage dreams.

Havel’s references upon references upon references create theatrical transparency in photographic collaboration.

A portrait of a confident young woman poses with a guitar, looking like Liz Phair in a room of candles, chandeliers, and a green plastic almost rave-wear style visor. A re-creation of the cover of no-wave artist Cristina’s 1984 album Sleep It Off becomes a shrine to her after she was taken by Covid earlier this year. A nude male figure reclines across a table, “come-hither”-y gazing at the camera and viewers with a nod to high school painting class – a muse who’s in on the joke. Theatre sets drip with magenta hues.

I met a.r. havel in early December for PhotoNola’s annual portfolio reviews. In our 20-minute art-speed date lightning round, his work stood out for its playful sincerity. “Fascinated by the power of queer and radical community resilience,” his work shows the mechanics behind his process, his deep love for pop-culture and art history, and photography’s ability, during these uncertain times, to be both cathartic and fun.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with a.r. havel

© a.r. havel

Jon Feinstein: "The tassels have tassels!" This line was the (perfect) introduction to your work when I landed on your website. Get into it for me...

a.r. havel: The actual line “the tassels have tassels” was a recurring joke between my studio assistant Morgan Landry and I. While constructing the sets for the quarantine queens / las sirenas series, I had amassed an obscene amount of tassels of so many sizes from French Quarter estate sales; if we weren’t sure what a scene needed, we’d just add more tassels. “Damn! Those are some maxi-tassels!” another friend quipped. But like a lot of things in my work, the personal anecdote has its accompanying cultural reference.

In this case, it was the comfort I found in a scathing review Roger Ebert gave Ken Russell for his outlandish Tchaikovsky bio-pic, The Music Lovers. The film had always been one of my favorites, and all the things Ebert was tearing Russell to bits about—the “grotesque jungle of incense and candlesticks,” the “fringe that has fringe”— all that baroque absurdism was what I’ve always loved about Russell. Reading the review was a jolt of validation: yes to maximalism, yes to decadent trash, and as is said every carnival season ad nauseam: “more is more.”

“Pasha of Joy” august 2020. set collaboratively designed and adorned with Pasha. lighting assist by Phoebe Vlassis. © a.r. havel

Feinstein: One thing that fascinated me when looking at your work is your nostalgia for 90s ephemera + pop culture. We talked about Liz Phair and others, who were part of my own early adolescence/ I grew up thru their heyday, but I understand you were much younger during that time. How does this fit into your own identity? Was this music/ culture important for you during your childhood/ adolescence or did it come later? Why are they important to your work and identity now?

Richmond-Havel: You know, I always thought it was more “the 80s” I was fascinated by and attempting to evoke. As a kid, I fell asleep to the 80s radio station and listened to my mom’s favorite music so much. So, I was singing Duran Duran and Emerson, Lake & Palmer more than the Backstreet Boys or Britney Spears, or whatever my classmates were listening to. I mean, my first concert was Foreigner and Bad Company—not my choice, but still. So, I’m always going back in time; in some ways, it feels like I have to play catch-up.

Through music, I drift into intense streams of what feels like research, but it's really just trying to get a sense of a time and cultural landscape through popular music. Did you know the creator of Italo Disco was from the Caribbean island of Guadalupe, an asshole so despised that when he was shot dead in his home, most peoples’ reaction was “what took so long?” Or did you know Sophie Muller’s first video with the Eurythmics, “I Need a Man,” was her final for film school; can you imagine that college crit-room full of technically-skilled bros watching Annie Lennox in high-femme drag?

These are the kinds of curious pseudo-historio-cultural scenarios that fascinate me; imagining the meta-narratives behind all the cultural images is often more exciting to me than the person or thing being spot-lighted. So it could be alt-rock Liz Phair, lower-east-side Phoebe Legere, Courtney Love next to a billboard on fire, or Rick James on the corner of Street Songs—it’s all worth getting lost in.

“La Divinatrix” september 2020. this collaboration with Xiamara Chupaflor is a mirror image of an ExVoto painting found at Mercado de la Lagunilla, CDMX. make up and styling by Xiamara, set and lighting by a.r. havel. infinitas gracias to Lisa Giordano and Andrea Narno. © a.r. havel

Feinstein: Can you talk about this work's connection to contemporary punk culture? We touched a little on this in our conversation at PhotoNola.

a.r. havel: I’m hardly your first contact for contemporary punk information; I do have a lot of friends in punk scenes making great music and heading mutual aid projects. One thing about New Orleans I love is that so many music scenes and identity-spaces cross over because you can’t make it as an alternative venue if you only cater to one group or sound. The “Shadow Play” series features two heroines of punk New Orleans: Monet of Casual Burn, and Pasha of Joy. This wasn’t necessarily an intentional ode to the community, so much as they both happened to embody the spirit of the imagery at hand.

Proud or not, I think I have more roots in smokey industrial goth clubs; that was my high school experience: me and Mexican goth punk kids who loved Bauhaus and Morrissey. I think San Antonio was similar in terms of size and genre crossovers. But then, I’ve always been someone who has straddled the lines of spaces; I came to New Orleans initially working for non-profit theater groups and was looking longingly towards the queer punks making d.i.y. performance on-the-spot, which often felt so much more inspired and alive than the devised work I was rehearsing for months.

“Silly Straw Genet” september 2020. reimagining “un chant d'amour” as an ‘80s Vogue spread art directed by Almodóvar. Owen Ever and Jacob Ryan pose. set assist by Morgan Landry. © a.r. havel

Feinstein: Beyond pop music and subcultures, there is also so much art history in your work. I see Picasso, there are clear shoutouts to Monet, then the photo references stretch from Sandy Skokglund to David Hilliard. Maybe even a queering of DiCorcia... so much... what else?

Richmond-Havel: Transforming and coalescing disparate inspirations, stories, and eras is a kind of intimacy for me. It’s a love-letter and a puzzle, and it’s really more an intuitive process as opposed to understanding how every part comes together. Take the quarantined queens / las sirenas panoramas for instance: the image itself is a kind of autobiography of artistic influences and experiences. It’s the culmination of working with a bunch of radical performance artists in San Antonio, a group spearheaded by queer Black playwright Sterling Houston—a man bemoaned by Amiri Baraka for doing cross-race and gender casting (white men played “Mammies,” Black women played plantation owners). It’s being fourteen years old buying a tiny acrylic painting by Franco Mondini-Ruiz, and then working with him one summer in my 20s washing wiry brushes congealed in gold plate.

My original inspiration for the panoramas was a Gered Mankowitz photograph that wrapped around an ABC sleeve for The Lexicon of Love. I didn’t know that they would look like Annie Leibowitz vogue spreads, but I also had Pierre et Gilles in mind.

In the same way music history is a huge influence, I think studying art history and photography history is a rich, rewarding experience. We live in a disorienting hyper-saturated ocular-centric culture; in some ways, tracing the through-lines keeps you sane, understanding the nuanced history of a gesture, style, or technique, how it passed from cool to passé, and back again. I’ve been loving reading photography critics of the 20th century because so many of their concerns feel hyperbolic or overblown for their time — how could they possibly handle Instagram! I’ve found also that the more a critic chides a photographer for being too absurd or untruthful, the more intrigued and inspired I am by the images.

“Cake and Kerosene” september 2020. taken on my birthday. Grant Higginbotham poses, styling by them. © a.r. havel.

Feinstein: We also spoke about a kind of "New Orleans aesthetic” - I saw an immediate connection between your work and Kristina Knipe's, and your first response, I think, was something like "oh, that's just New Orleans." If you could describe that aesthetic, what is it?

Richmond-Havel: Some things that come to mind as a quintessential New Orleans aesthetic: a rainbow refracting off an arc of piss one carnival dawn; that one time Bourbon Street smelled extra bad because a mixture of rotting kitchen grease and mardi gras beads had congealed and stopped the sewage drains; an ambulance parting a huge mass of costumes, one of which is a very drunk pope who rushes to the gurney to give the jittering patient an outstretched papal hand; suddenly being okay with amoeba-infested water and having to fix your flooded-out engine (again) because goddamn that sunset really is magnificent; getting kicked out of an heiress’s house because you just met your new best friend by putting on a show of whipping her pussy with white carnations.

A lot of us would like to exist in that fleeting glittery high before you start to feel your jaw and wonder: oh no, is magic all just a mirage? Oh shit, all the -isms still exist! The house is on fire and I’m holding a match, but I was just trying to light the party candles.

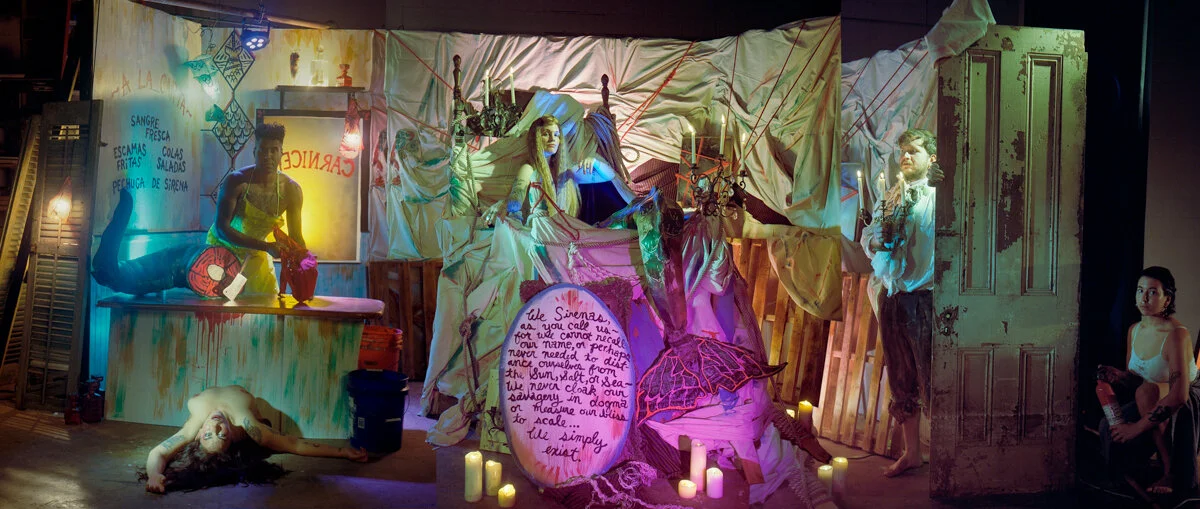

The Quarantine Queens Rehearse their Production of “The Butchers of Las Sirenas” in a Time of Plague

© a.r. havel

Feinstein: Your work also hinges on elaborately built sets, which I understand you do mostly yourself/ comes from your background as a set designer.

Richmond-Havel: Sometimes the first way you do something becomes the way you do it all the time. My first set design was for this play some friends put on advertised as “queer silent Shakespeare.” It was Romeo & Juliet, but it was a bait-and-switch. The whole point was that the production falls apart on purpose. The venue owner comes out after Mercurio gets hit for real and yells “fuck!” By the end, the set collapses in on itself, chickens wander around for no reason, and industrial-size fans send sheet-music everywhere. That set was gaudy, gold, shellacked with old bits of metal, and found objects. It was also very simple, in fact its simplicity was kind of a joke. And that’s so often how my ideas take root, “wouldn’t it be funny if...”

My mentor in scenography is a devised theater genius named Jeff Becker. He can create space out of anything. Jeff had a workshop once where all the participants could use were yarn and paper-plates. He taught me how to find the landscapes in any and everything. The thing about photography, as opposed to theater, is that it crops a landscape.

So, sometimes it's about embracing the given frame, as is the case with the “Shadow Play” series. Those sets were built to accommodate the shape of the negative, whereas the quarantine queens / las sirenas series wants to expose everything. If I had the means, I would have built a giant gold-frame to enclose the warehouse space around the set; I love layering space as though it’s all a two- dimensional collage. Of course, I love Robert Wilson’s work, even if his space is so vacant in comparison; it’s all those angular shapes in a world that exposes itself so seamlessly, harkening back to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari sets and Russian Futurist theater.

The Quarantine Queens Rehearse their Production of “The Butchers of Las Sirenas” in a Time of Plague

© a.r. havel

The Quarantine Queens Rehearse their Production of “The Butchers of Las Sirenas” in a Time of Plague

© a.r. havel

Feinstein: Digging deeper into that, what really struck me about this work and its connection to the theater is also its transparency of process -- thinking a lot about Brecht's making visible his stage directions - which you are kind of doing with photography.... can you talk a bit about this and where it fits in for you, your process and why you're drawn to do it?

Richmond-Havel: I had a good friend and collaborator once joke about my high tolerance for bad art. I mean just terrible stuff that he would have no qualms walking out of. It became a game: texting him, saying “hey, I’m in Croatia at this punk squat where this Zionist is dressed in a party-city Spiderman bodysuit and talking about squashing the enemy with his Spidey-silk.” “Girl, get OUT of there!” he’d always reply. But, on the edge of every bad performance are people like spiderman’s wife, the director, pantomiming and lip-syncing his every line with way too much pizzazz.

A woman who threatened to leave a punk squat because the accommodations were not up to par. All of that suddenly makes the god-awful performance worth it and one of the festival’s highlights. Some people have told me that my life is wild or over-the-top; “you need to write your memoir” is a nice way of saying “I’m glad it didn’t happen to me.”

But, the truth is, the absurd and entertaining part of things always lies on the edge of the “real” experience. So, adding these stories into a scene is a way of enlivening it, imbuing it with a world-making kind of quality. Hopefully, you are intrigued, bordering on confused, creating a whole made-up story from one gesture. And maybe you tell yourself that story enough times that it starts to become a memory, and then you have to wonder: was Spiderman’s wife in the front row? Because, now that I imagine it, I am just seeing Andrea Martin doing one of her classic bits.

The Quarantine Queens Rehearse their Production of “The Butchers of Las Sirenas” in a Time of Plague

© a.r. havel

The Quarantine Queens Rehearse their Production of “The Butchers of Las Sirenas” in a Time of Plague

© a.r. havel

Feinstein: You made all of this work during the pandemic. How much does quarantined life play into how you're thinking about this work? Has it helped and/or stood in the way of your process?

Richmond-Havel: I pulled my grandfather’s medium-format cameras out in February and took some photos with his Mamiya 645 during mardi gras. As he used the cameras to shoot weddings, I was devising a project to “culturally re-adjust” the lenses on his cameras by doing queer family portraits. It was only two weeks later that quarantine began. I realized that photography was a great artistic practice as opposed to theater or performance art.

Of course COVID-19 has created severe limitations on our work; but, I gotta say, I love creative constraints and creating workable containers within them. The most interesting thing about quarantine, especially the Springtime when the quarantine queens / las sirenas panoramas were made, was that people were starved to create and they were eager.

People were saying yes and trusting and it feels incredibly important for me to name some of the people whose work is on display here. Costume designers like Willow Shaughnessy, Darryn Johnson, and House of Calamity. Sage Franz created custom oil paintings, Ashely Hooper made a life-size mermaid mosaic, my lighting designing collaborator Alex Hennen Payne. My mentor Jeff Becker who graciously lent us his studio. My now dear friend Morgan Landry, who showed up one afternoon and came back every single day. All these people remind me that the spirit of truly fulfilling art is collaboration.