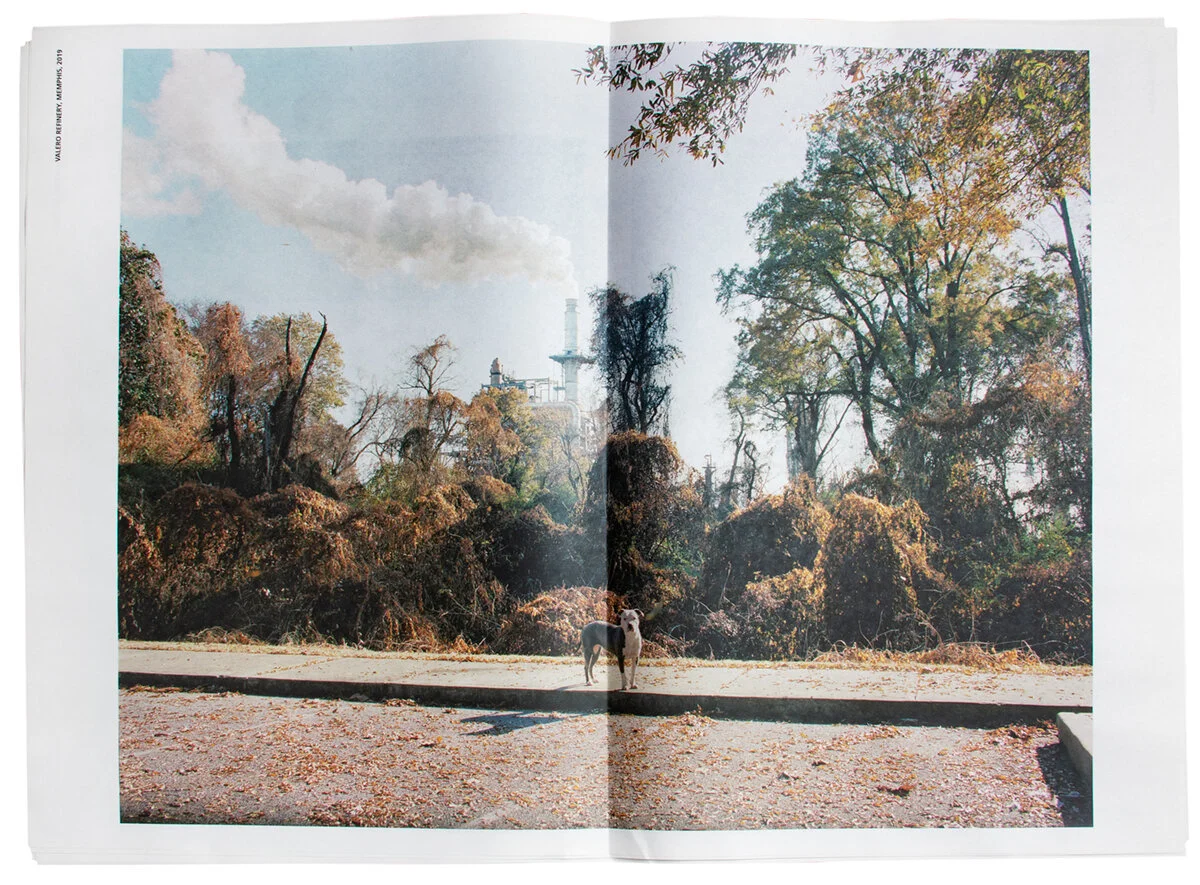

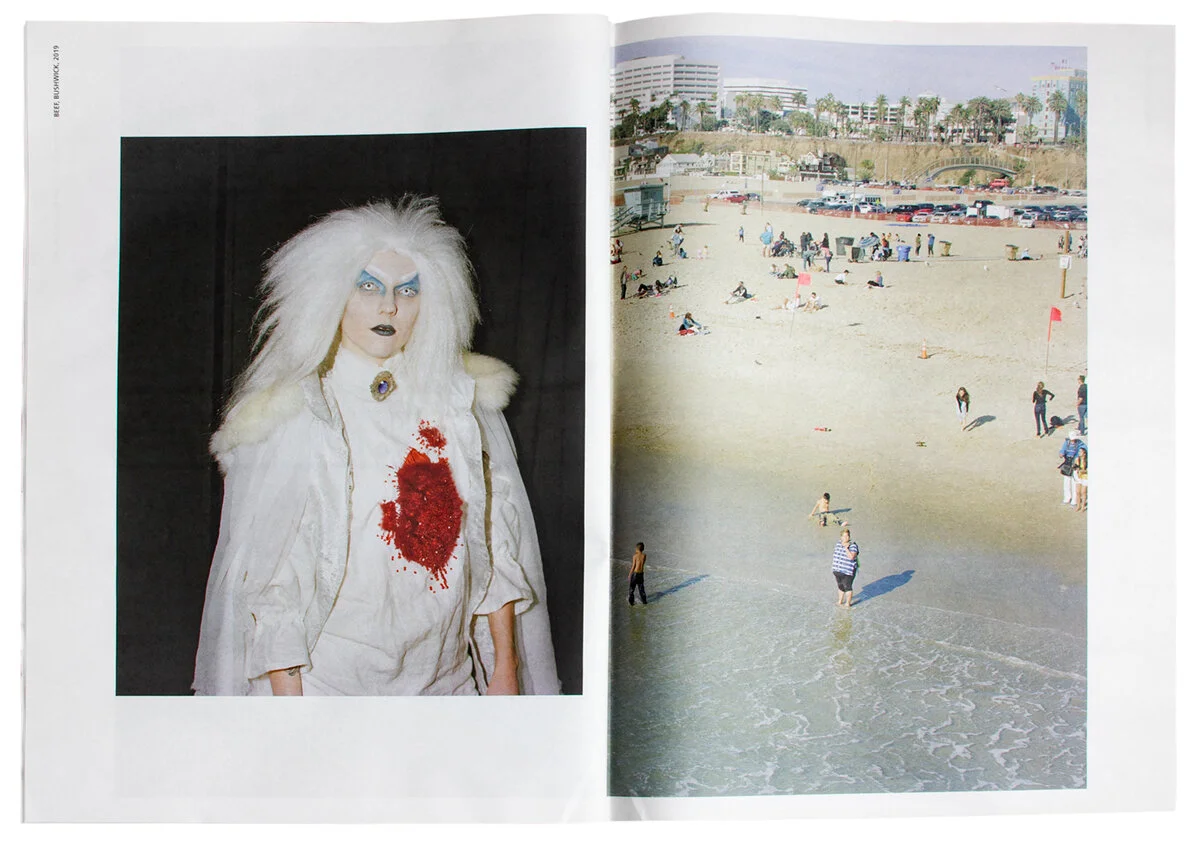

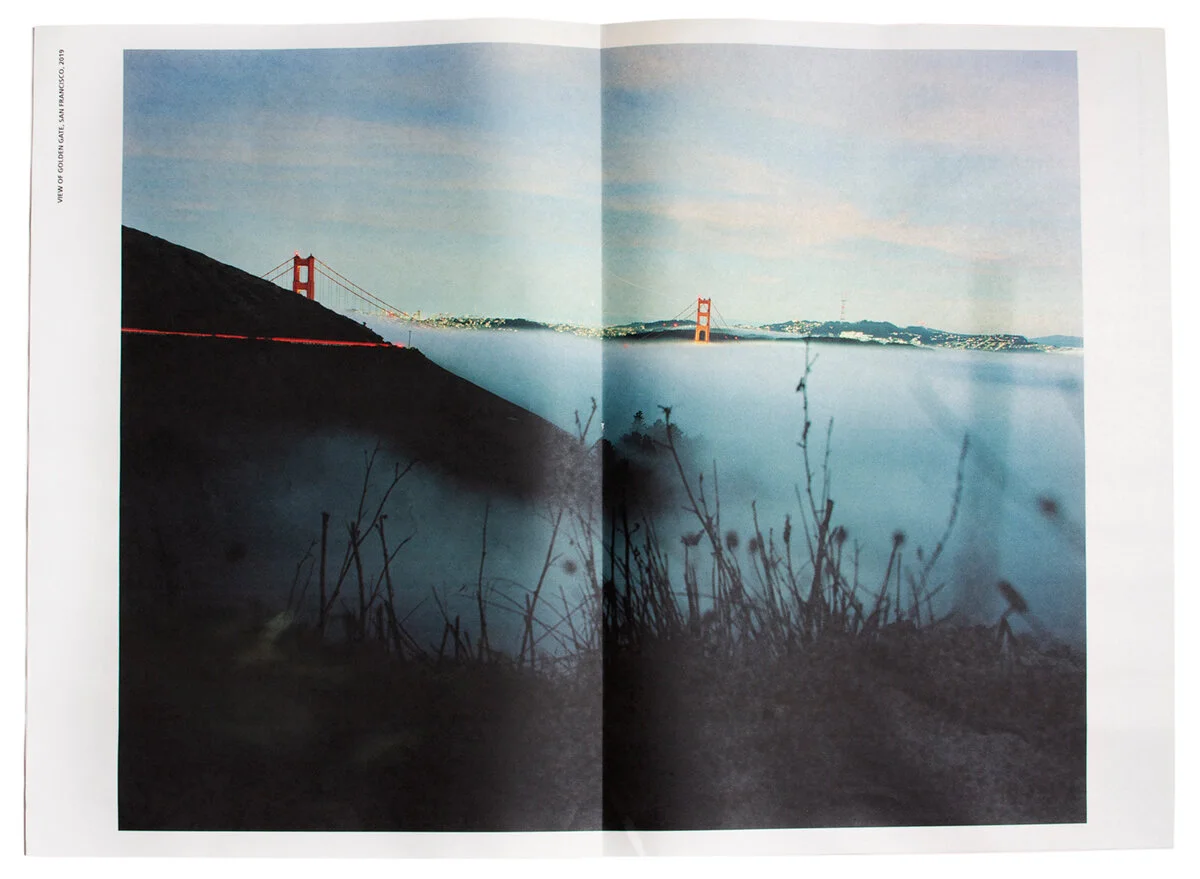

June T. Sanders speaks with Kelsey Sucena on Paralytic States: Sucena’s collection of essays and photographs about coming into themself as a trans*non-binary person in post-2016 America.

Kelsey Sucena is a trans*/nonbinary photographer, writer, and park ranger whose work rests at the intersection of photography and text. Their most recent work is a multi-disciplinary publication featuring writings and photographs made across the country in the wake of the 2016 election.

Kelsey’s work has an abject honesty and vulnerability to it. It is in some parts a nod and a contribution to auto theory and its champions like T Flesichmann & Mackenzie Wark. In others, a messy swim through the landscape of gender, transness, capitalism, and the American experience.

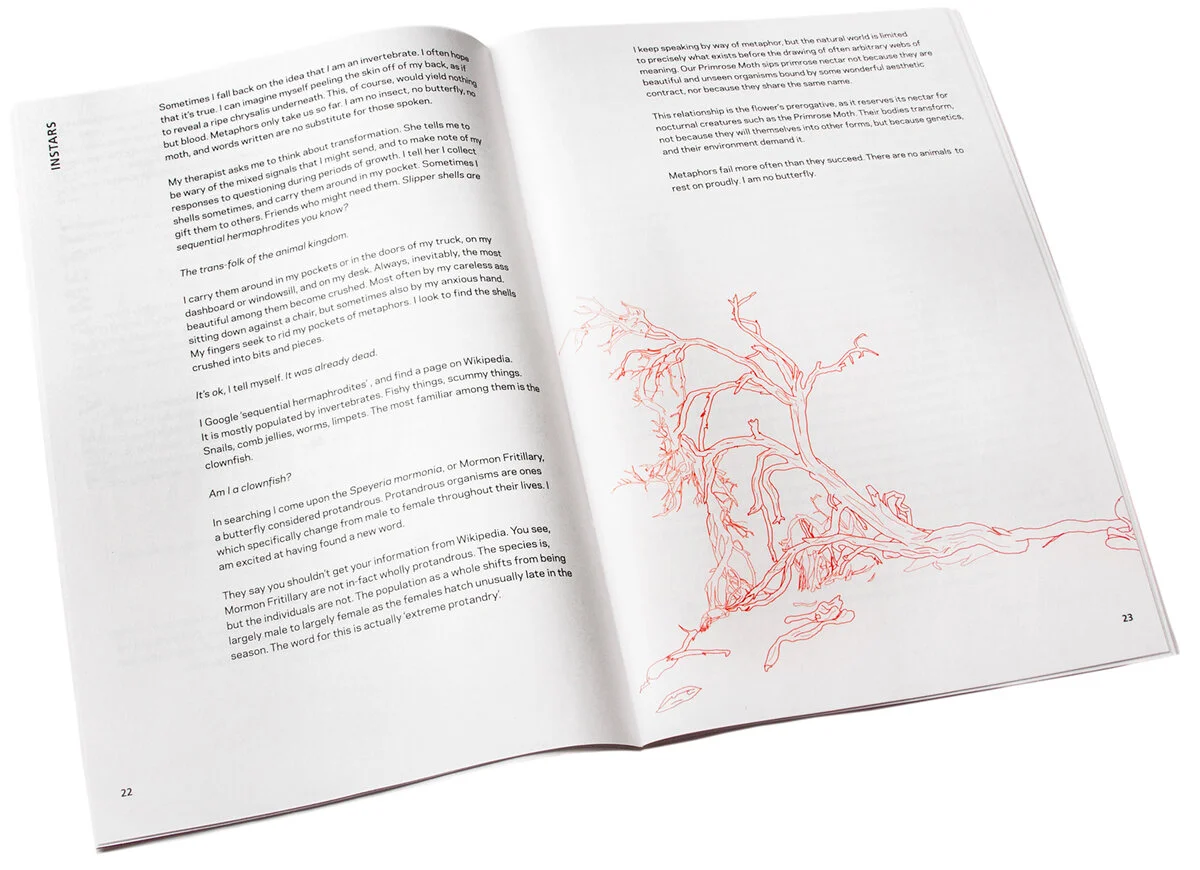

Paralytic States is far more than a housing for recent work. It is itself a force; a towering newspaper that stretches the possibility of image and text where the two mediums don’t just support each other but complicate each other’s narratives. Their process and insight puts them in the camp of artists who espouse the power of urgent, radical, and experimental publishing. And to me, mark a new lineage of poetics in image-making.

But beyond all that, it is a reminder. To witness - to hold - and to care. In their own words: “I am here to say that we are drowning because we have yet to read the waves.”

June T. Sanders in conversation with Kelsey Sucena

© Kelsey Sucena

June T. Sanders: Thank you for taking the time to talk to me Kelsey. Can we start by telling me how this project "Paralytic States" started for you?

Kelsey Sucena: In a literal sense “Paralytic States” began on a road trip I took in 2016. I was in Seattle when the election results came in, so what had felt like this fun/clichè right of passage was suddenly fucked. At the same time, I was wrestling with coming out as trans*/nonbinary. After that road trip, it felt urgent to resituate myself within the world and to reevaluate whether or not coming out was safe to do. My writing became a space to work through those feelings, while the photographs helped me to feel grounded.

But, I sometimes joke with folks that projects like this begin for me when I find a title to package them under. Before I had the name, “Paralytic States” was a loose assemblage of essays and poems, and photographs made over the course of four years. Even though it's still something of a loose assemblage, the title gave me something to rally around. It imbued the project with a sense of continuity and helped me to shape the final collection into something greater than the sum of its parts.

Sanders: Conveniently this leads me into something I was hoping to talk about — which is your writing process. You've done writing in collaboration with Paul Soulellis and the Queer Archive work, as well as during your time with Image Text Ithaca. And it's all so poignant and pithy and seems to resituate my own relationship & thoughts between words and images. Could you tell me what the relationship looks like for you?

Sucena: When I was young I used to write poetry often. It was something that I was both proud of because I thought I was pretty good at it, and ashamed of because it felt like either a feminine or pretentious pursuit. Around the same time, I began to make photographs, enamored by the way they rendered space and time.

As I studied photography with greater seriousness, I left writing behind. I think it takes a certain degree of internal validation to pursue either medium, but photography was conveniently buttressed by the world around me. Because the landscape seemed valuable, or because the people I photographed were valuable, photography echoed with value in a way that was not as readily apparent in my writing. Writing felt too internal. Too solipsistic to be worth anything to anyone else.

It took my time at Image Text Ithaca, studying with folks like Paul Soulellis and working with Queer.Archive.Work to learn that sometimes art, even at its most internal, can be valuable to other people. That I could present words to friends and see that they recognized parts of themselves within those words completely transformed the process for me. So now I practice both mediums with equal seriousness, and while there is a more theoretical and aesthetic framework for my combined use of image and text, I try to think about them in personal terms. Both are tools for communication, allowing me to make and express observations I might otherwise shy away from.

Kelsey Sucena’s Paralytic States. (Zine photographed by Dana Stirling)

Sanders: 'Paralytic States' seems to be a nice amalgamation of these things; a publication, a photo essay, and what I read as long-form autotheory. How did you come to these forms, including the large-format newsprint?

Sucena: I try to open myself up to the possibility of failure when I'm making work. This gives me room to experiment with forms, mediums, and concepts in a way that feels organic and validating. Through experimentation, I realized that I have difficulty choosing between intuitive and intentional frameworks for the production of art. The relationship between image and text within a publication is complex enough that it seems to open space up for a bit of both. I can key back and forth between them, making way for the emergence of new ideas. However, I quickly realized that I felt the rhythm at which we tend to read image and text is generally awkward, and so I decided early on that I wanted the images and the words to be tangibly separated into two related bodies, atomized but orbiting each other in a way that feels less didactic and more conversational.

As to the large format newsprint exhibition, there are a few reasons I chose to employ it as the vehicle for “Paralytic States.” For one, there is a wider tradition I wanted to access which is grounded within history, whether that is embodied within popular newspapers like the New York Times as a vehicle for current events, or within the radical/queer publishing tradition of projects like Steve Lawrence’s “Newspaper” and its later iterations, as well as projectd produced by Q.A.W.

At the end of the day, however, with a pandemic upon us, so many folks out of work, and protests in the streets, I resolved months ago that if I was going to ask people to spend time with my work I didn’t want to ask them to spend money on it as well. I decided to gift this edition of “Paralytic States” to others as an act of solidarity. The affordability of newsprint has allowed me to do that.

© Kelsey Sucena

Sanders: Right. Accessibility is huge; It's not radical if it's not accessible. In language, affordability, or any other aspect.

Sucena: Well yes. Exactly!

I believe that any barrier, whether it’s of language or it’s financial, would be counterproductive to us if we’re talking about building support for radical causes. That’s not to say that I believe radical artists shouldn’t feel empowered to monetize their work, nor do I feel like it’s my place to call my own work radical (though I certainly hope it is). What I mean in making this work “accessible” is that when I think of my work, and my philosophy, and the circumstances we’ve been thrust into by the rotting systems of late-capital, it makes sense to me to give this work to other people as much as I can afford to do so. The affordability of newsprint as a material enables that.

So accessibility has very much been a concern for me. I believe that concern is there in the language and the photography too. I’ve tried as much as possible to ground both of my processes’ within familiar languages, visual or written, and to try to explore complex issues around trans* identity, capitalism, and radical politics in ways that don’t feel too academic. I hope I’ve been successful, at least to a certain degree.

Paralytic States © Kelsey Sucena (zine photographed by Dana Stirling)

Sanders: I do see this messy relationship between transness, capital, politics & poetics, and the American condition — both in how you navigate the world and how you document and make. Can you talk about this? About — I suppose — moving through space and landscapes and emotional architectures?

Sucena: Ever since I came out I’ve had this fear of stagnancy. This discomfort with the prospect of paralysis that keeps me moving through landscapes, whether they are physical, emotional, or dialectical. So, when I write or when I photograph I often feel the need to move swiftly through all of these different spaces, in order to try to connect them and to make them feel poetic without letting myself get too caught up in any one idea. And yet I'm usually caught up in them. Totally entangled and often paralyzed.

So it is messy. Maybe in the way that identity is sometimes messy? We're all subjects to systems which we don't consent to. To capitalism. To gender. To race. To class. To national identity. And I think that making sense of the complex ways in which those systems intersect, and impact us is part of the work of finding out who we are. Of gaining a sense of agency over our identities and our lives. Do you ever feel that way?

© Kelsey Sucena

Sanders: I do. So much of the time. I also feel as though so much of what we do as artists and as 'deviant' bodies is to try and carve out space outside or beyond these systems. I'm wondering if, related to this, you see your work more as a kind of documentation or as an imagining or recontextualization?

Sucena: I’d say that my work is embedded within a documentary tradition, but I wouldn't exactly call it documentary. The word you’ve offered here, recontextualization, feels perfect to me. So thank you for it!

The last few years have been difficult to say the least. That’s true on a personal level and it’s true on a political and cultural level. Moments like this demand recontextualization. I’ve had to explore my relationships, with gender, with people, with the world, in ways I didn’t anticipate. So yes. Creating “Paralytic States” has been an act of recontextualization as I’ve struggled to carve out this space for myself.

Paralytic States © Kelsey Sucena (zine photographed by Dana Stirling)

Sanders: There's a small piece of your writing that goes: "My photograph feels grief-stricken. But then, all photographs feel grief-stricken to me." I was hoping you could elaborate on that for me.

Sucena: Lol. When I wrote that I thought that maybe I was being dramatic. And I’m not sure that everyone would agree with me on that point, or even that I always agree with myself. But of course, there is so much writing about photography as this melancholic thing. So much theory out there which attempts to essentialize it. Often theory points to the relationship between photography and death. I think of Roland Barthes for example.

But when I wrote that essay I was also in mourning. I still am. My father had recently passed away and so that essay is all about the end of our relationship, mediated as it was through these two photographs. When I look at photos my affect naturally drifts toward mourning, and while I try to avoid essentialism it's hard not to feel as though photographs are generally sad objects. Often they’re these sort of futile attempts at preservation which speak genuinely to our fears, desires, and hopes. And I know that’s not true for everyone but I can also be a bit of a sadgirl. I try to let myself be naive here and there.

Paralytic States © Kelsey Sucena (zine photographed by Dana Stirling)

Sanders: That leads me to something I always like to ask: What does photography, or images, do for you? Emotionally, Physically, or Socially?

Sucena: That’s a good question. And one I think about often. I'm realizing that photography actually plays a significant role in the maintenance of my mental health. Whether I've been out as Trans*, closeted, or unaware of that latent identity, dysphoria has always served to deeply alienate me from myself, other people, and the planet. I have this tendency to dissociate when I'm feeling shitty.

So then, photography comes along and becomes this thing that forces interaction, awareness, and presence. On one level it's meditative, returning me from that dissociative state to the environment surrounding me. On another level it's social, helping me to talk to other people and generally avoid feeling as atomized as I sometimes do. I've called it the “re-connective tissue between me and the material world", and I'm hopeful that for other people it can serve a similar function. Because we're all so alienated and atomized under capitalism. Maybe photography can help us connect and build solidarity? Or maybe I really am just naive.

Paralytic States © Kelsey Sucena (zine photographed by Dana Stirling)

Sanders: I’m curious to know how this year might have shifted your relationship to ‘work’ or making or productivity. Could you share some thoughts on that?

Sucena: This is something that’s been on my mind lately. From every standpoint it seems this year has done quite a bit to flesh out how truly dire things are for people. This has had me dwelling upon labor more generally, but also on the connection between labor and (art)work. I'm not sure that I've drawn any conclusions from this line of thought, but I am starting to feel more critical of the art world/market and the function it serves in the perpetuation of oppressive structures, and especially those which work against young or emerging artists. As artists we have this tendency to tie ourselves up into knots worrying about our productivity. I think that in doing so we often sell ourselves short.

Many photographers I know have responded to this pandemic in brilliantly creative ways, circumnavigating the need for proximity or shaking up their practice to keep the momentum going. I haven't been able to do that as much. I feel like I'm slowing down, and I'm trying to feel ok with that, validating my need for rest after finishing a big thesis project like “Paralytic States”. Artists don't need to run ourselves into the ground. The narratives we sell ourselves about hard work and productivity can be damaging, and counterproductive, especially if we think (as I do), that artists should model new ways of living with and thinking about the world that go beyond the dog-eat-dog of capitalism. Just because I call my work "work" doesn't mean I have to treat it like labor. And if I'm going to treat it like labor then I'm going to affirm it as a valuable, powerful and political thing.

Paralytic States © Kelsey Sucena (zine photographed by Dana Stirling)

Sanders: What’s next for you Kelsey?

Sucena: There are a few things I have coming up. Nothing monumental, as I mentioned I’m hoping to take things slowly, but I am excited about an Open Call which I’m curating with my friend John O’Toole over at Oranbeg Press. We’re asking artists to dwell a bit on the idea of “refusal”, especially as it relates to politics, economics, and culture. It’ll be a small online show, and I’m not sure yet exactly how we’ll display everything, but I’m looking forward to the conversations it’ll foster. The deadline to submit is December 21st.

Beyond that, I’m excited to share the afterword I wrote for a new group publication by Efrem Zelony-Mindell and the folks at Cumulus photo. You can order a copy of “Running to the Edge of the World” now. And keep an eye out for Queer.Archive.Work at this year’s online New York Art Bookfair. We’re working on an exciting project that’s still in its early stages of production, but we’ll be there and we’d love to have you visit.

Finally, I still have copies of “Paralytic States” available to folks who are interested. As the edition is relatively small I’m hoping to send these last ones out to folks who really want to read them. They’re welcome to DM me if they’d like a copy. I’m also looking for photographers to collaborate within 2021, so if anyone is hoping to work on an image/text project, and would like to experiment together please feel free to reach out.

Thank you again June! This has been one of the most exciting conversations I’ve had in 2020. I look forward to keeping in touch.

---

Kelsey Sucena (they/them) is a trans*/nonbinary photographer, writer, and park ranger currently residing on Long Island. Their work rests at the intersection of photography and text, often within the bodies of performative slideshows and photo-text-books. It is centered broadly upon the United States as a site for anti-capitalist, queer and critical reflection. Kelsey is a recent MFA graduate from Image Text Ithaca (2020), a former work scholar at Aperture Foundation, and a freelance writer with contributions to Float Photo Magazine, Rocket Science, and 10x10 Photobooks.

June T Sanders is a trans artist living in the fields of rural Washington State. She is currently an assistant professor with the digital technology and culture program at Washington State University.