© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

Amani Willett’s new book A Parallel Road challenges the glamorized narratives of the American road trip with experiences shaped by fear and violence.

The American road trip is a privileged photographic and literary rite of passage. Coming of age on the open road, it's largely a trope of carefree travel primarily enjoyed by white Americans. Photographers Robert Frank and Jacob Holdt, whose work pointed to racial, economic, and social inequality in the American landscape, did so with unfettered access – without fear of racist violence. And while Frank, who was Jewish, was likely in danger of antisemitic attacks, his ability to pass as white made his experience far less vulnerable.

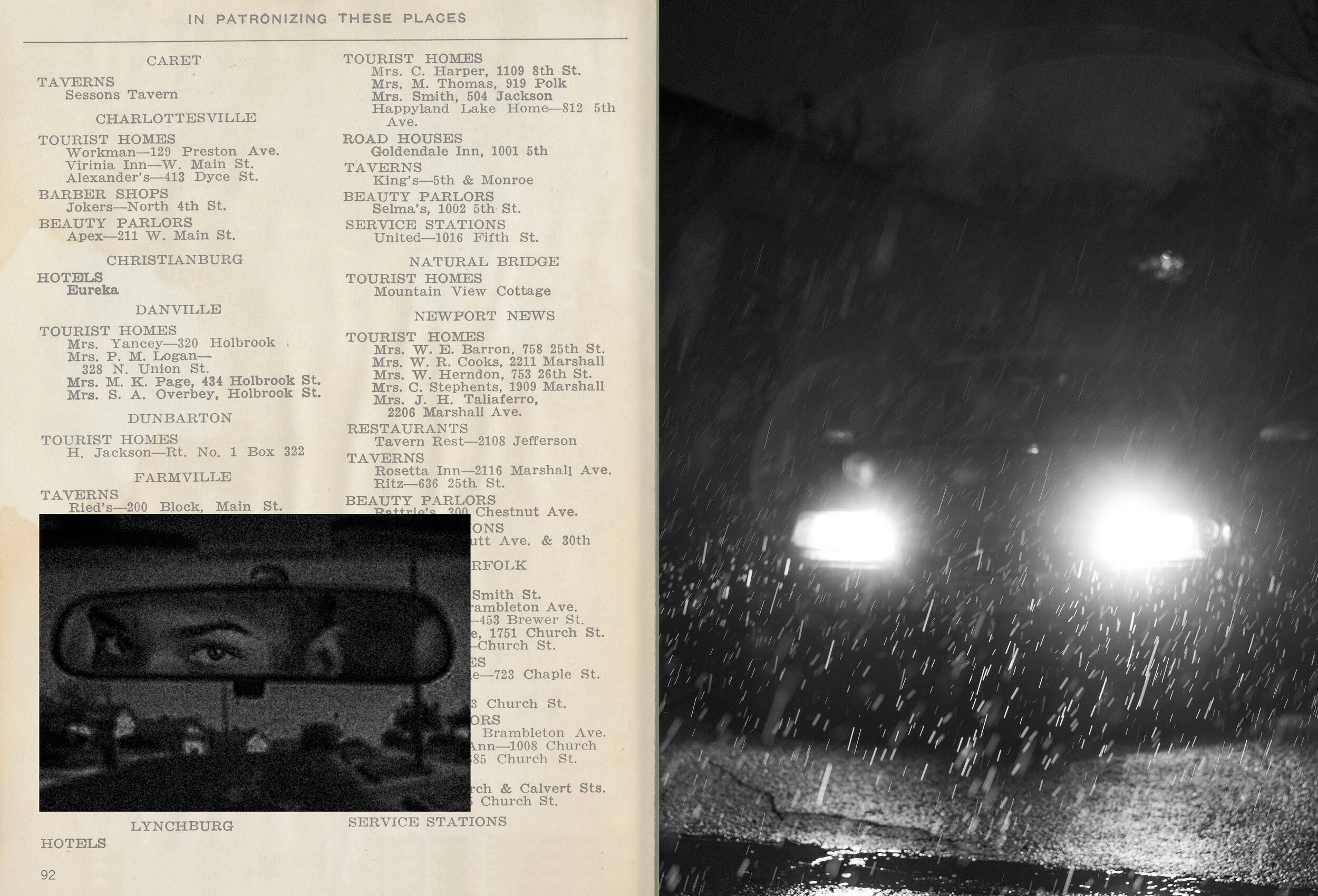

A Parallel Road, published by Overlapse Books, offers an alternate history, traversing many Black Americans' experiences driving on American roads for the past 85 years. Based on conversations with friends and family about their histories, he pairs archival illustrations, maps, and vernacular images with his own photographs to present a haunting picture that raises new questions with every page. As the United States continues to see state-sanctioned violence against people of color on the road, A Parallel Road asks how long it will remain an expanse of terror.

I spoke with Willett to learn more about his experience, and to dive deeper into the process behind making the book.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Amani Willett

Jon Feinstein: Let's talk about the title: my understanding is that it's a reference to the glamorization of the American road trip, the long winding rite of passage for white America and its sinister, violent parallel for Black Americans afraid to travel thru white America....can you talk a bit about how you came up with it?

Amani Willett: I’d like to preface my comments for all of these questions that this is my perspective based on my experience and research - I can in no way speak for the multitude of ways Black Americans have experienced the open road or American life.

Feinstein: Thank you.

Willett: With regard to your question, that description is a really great distillation of the idea. Most of us are familiar with the term “separate but equal” from American history. I was thinking about this phrase when I came up with the title. This falsehood is laid bare in the divergent experiences of white and Black Americans on the same roads. During the Jim Crow era, while both were traveling the same widely-celebrated new interstate highway system, their actual experience of that physical space could not have been more different.

In popular culture and literature, the American road has held a mythological position of freedom, exploration, and pursuit of the American Dream. Joining this pursuit has been complicated for Black people and represents just one of the many ways that Black Americans have been denied full participation in the American Dream. The reality is, for Black Americans, the road has been a site of fear, potential violence, and even death.

Adding to the idea of a parallel experience was the robust new economy opened up for Black America as a result of the segregation laws in Jim Crow America: There were hotels, restaurants, night clubs, salons, etc, that catered specifically to Black Americans and provided a completely separate experience while traveling. This parallel world wasn’t just for safety but also for leisure and entertainment.

So while Black Americans were traveling in the same America as their white counterparts, their experience of that space was experientially and psychologically divergent and one that was also potentially dangerous.

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

Feinstein: Most recently, Lovecraft Country comes to mind, though entirely different in presentation. Have you watched the show, and do you think of A Parallel Road in context/conversation?

Willett: I did watch Lovecraft Country. There have been a few shows, books, and movies that have come out in the past couple of years about the Green Book and so of course when I see anything that’s related I’m interested in learning more. Lovecraft is very interesting in how it uses the metaphor of the horror movie genre to represent the sense of terror and psychological trauma experienced by Black Americans. It’s a Jordan Peele production and it explores the same metaphors Peele used in his wonderful movie “Get Out” to look at the psychological scars of institutional racism.

I do think there is a direct connection between Lovecraft Country and “A Parallel Road.” Both try and find ways to express the intense psychological, emotional, and physical trauma that Black Americans have experienced as members of American society.

While both works deal with race and the American road, it’s important to remember that these issues go back to the founding of our country. It’s horrifying when you realize this suffering has been carried on for centuries. The question becomes how do you show the anguish, how do you symbolize those wounds, how do you convey the sense of fear of potential bodily harm that’s been inflicted upon relatives and ancestors for hundreds of years? In that way, there is a shared mission with both projects, although stylistically and in the way each uses imagery they couldn’t be more different.

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

Feinstein: Was A Parallel Road initially conceived of as a book? What did your thought process look like?

Willett: From the outset, I always knew “A Parallel Road” was going to be a book project. Conceptually, reproducing an original version of the Green Book and then layering an evolving history of race and the American road on top felt like an important gesture. Advertising images from the 1940s and 1950s were used to symbolize white Americans' experiences of the American Dream. These images at the beginning of the book illustrate the relative freedom, independence, and innocence they experienced while traveling during the Jim Crow era.

As the book progresses, the narrative begins to become more ominous with images of car accidents and signs warning Blacks not to be seen in town once the sun goes down. These signs are a reference to Sundown Towns - towns all across America where Blacks were forbidden to be at night. If found, they faced intimidation and violence. Deeper into the book, historical images of intimidation and violence against Black bodies are put into conversation with my contemporary images of Black motorists who have been the victims of police violence - emphasizing that the problems of the past are unfortunately still very much alive in the present. I find it quite sickening that this problem has persisted for a hundred years and by having contemporary images in direct conversation with images made a century ago, I hope that viewers of the book feel the same.

At the book’s end, I attempt to show that despite the history of violence experienced on the roads, Black Americans keep getting in cars and taking trips, refusing to give in to the history of violence and oppression meant to limit their ability to live in the same America that has been attainable for White Americans.

Ultimately, the American road trip is a microcosm for examining race relations in America and symbolizes the larger systemic, structural powers in place that have limited opportunities for Black Americans.

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

Feinstein: The volley of archival images with your own photography has been a big part of your process and practice over the years. Why was it so important and unique to this book?

Willett: You’re right, using archival images and other forms of media have been a strategy that’s become more prevalent in my work over the years. It started with “Disquiet,” became more prevalent in “The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer,” and has become even more important in this new body of work.

“A Parallel Road” spans about a century and also deals with very specific real-world events. I can’t go back and photograph things that happened 100 years ago but I can research archives to find images that are important to the story I want to tell. For example, by finding and using vernacular images of lynchings from 100 years ago and comparing them to current images captured by smartphones of police killings, the systemic violence against Black people can be seen across time.

Although mediated with different technology and oppressed through different means, both forms of images are addressing the same fundamental issues that have remained persistent over time. I find that juxtaposition quite shocking and revealing in its own right and so that sense of history is one of the areas I wanted to explore in this project. But then I can also make contemporary images of people who have suffered attacks or been victims of racial profiling which adds another dimension to the project and connects their experiences to a shameful legacy. When I first started sequencing the book I found it quite powerful to see the contemporary images in the context of the historical images.

On a really basic level, the world is a complicated place with complex histories and stories. So when telling stories that involve history or long expanses of time I’ve found working with just one form of imagery feels too limiting. My hope is that by using diverse forms of images and various strategies for sequencing, new and surprising ideas emerge.

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

Feinstein: What's your relationship to the people in the found photos?

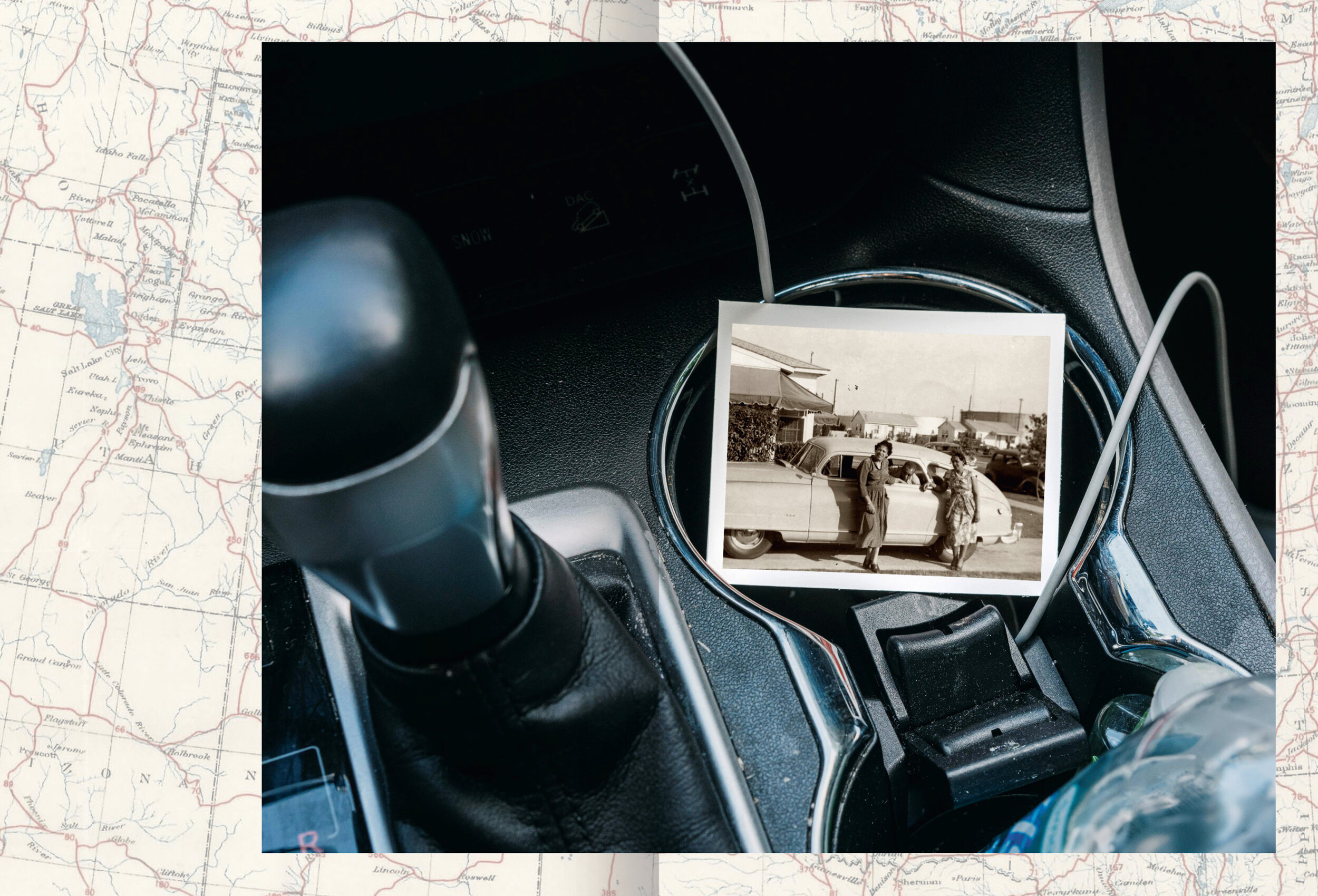

Willett: One of the main reasons this project came to be was a direct result of conversations I had with family members over a number of years. I was riveted and saddened to hear of their own experiences on the road as Black Americans. As a result, the project became very personal and I wanted to have my family help represent the injustices faced historically by Black Americans.

I have a large, close, and very supportive extended family. Once I began to understand how I wanted the project to take shape I reached out to my relatives and asked them to send me any images from their personal archives that contained images of cars. I spent months scouring the incredible images that they so generously shared. I was amazed to find images from the 1930s all the way to the present day. All of the historical vernacular images of Black Americans with cars or while driving are of family members. Bringing these familial images into the larger conversation about race and the American road felt quite profound.

Most of the contemporary images I made of people in cars are also family members - many of whom have experienced profiling or harassment - so there is also a strong, important family connection between the newer and archival images. The images span the arc of the book.

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

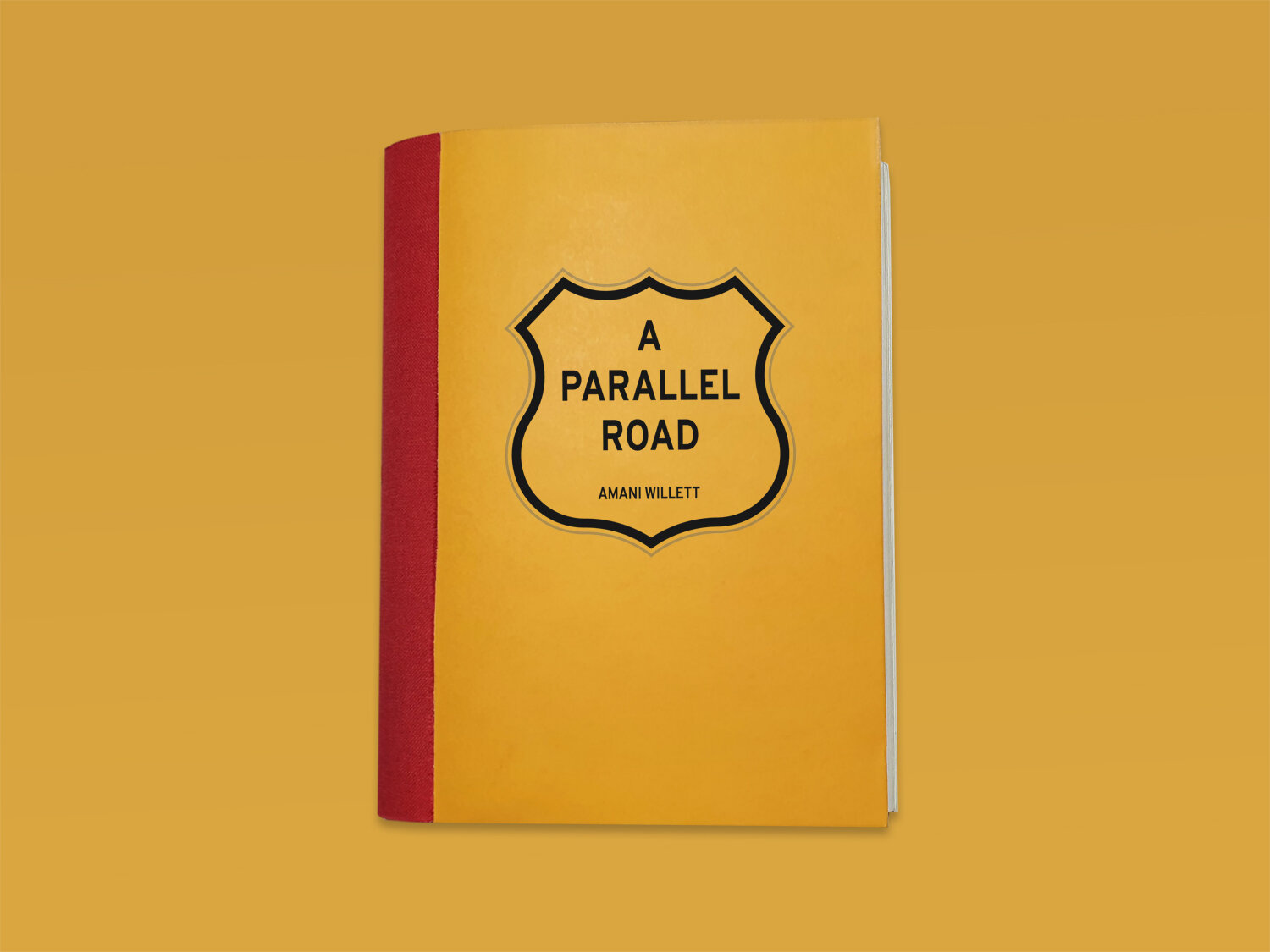

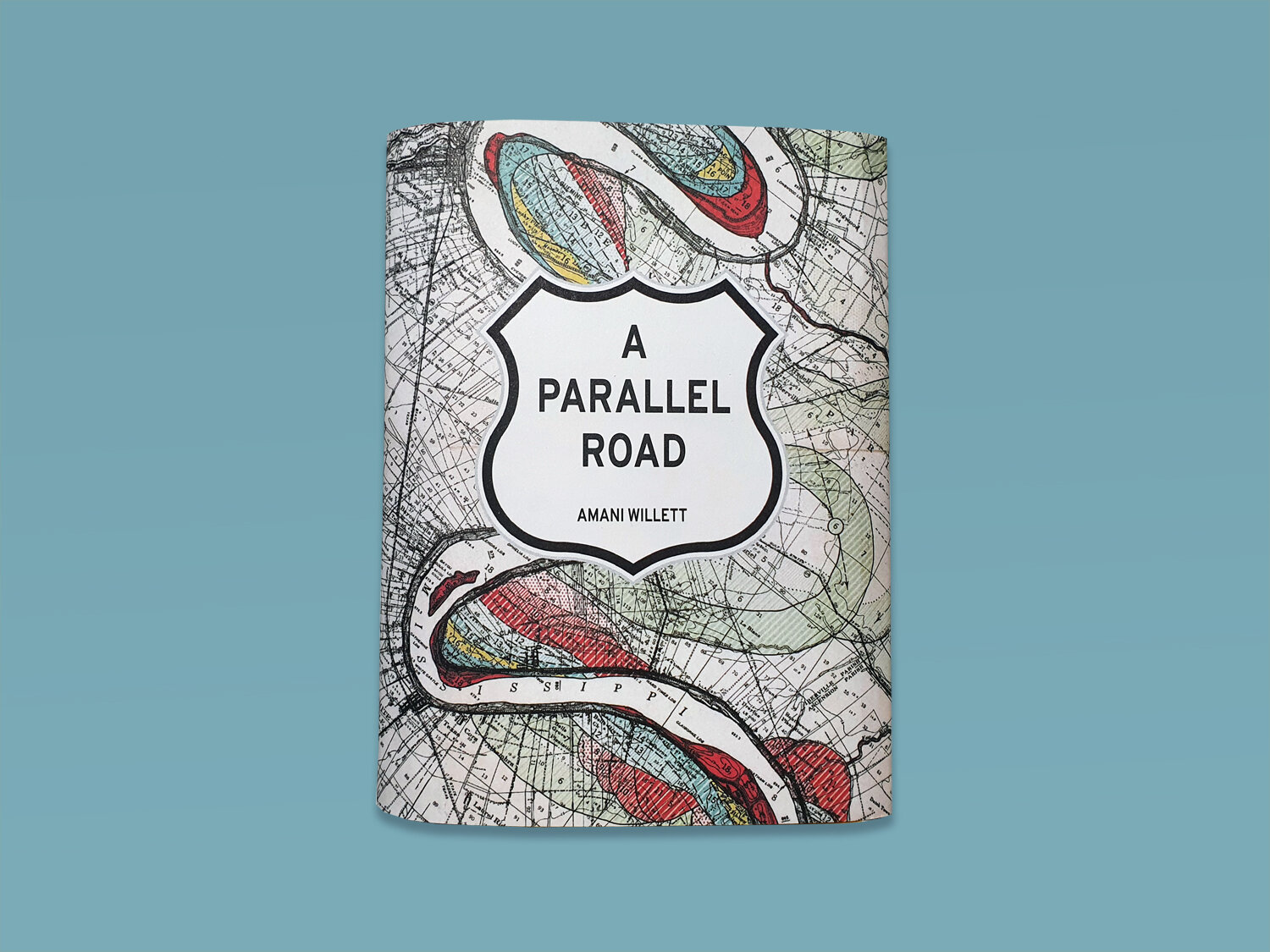

Feinstein: I'm interested in your decision to print the book small. Page-thick/ full of images and text but 5x7 - relatively intimate - just larger than pocket-sized. Was this decision in reference to the Negro Traveler's Greenbook?

Willett: Thank you for the observation. Yes, “A Parallel Road” is the same size as the 1940 edition of the Green Book and uses a similar hand-sewn saddle stitch as the original. I wanted “A Parallel Road” to have the historical connection to one of the original versions of the Green Book so that the sense of history and time was immediately perceptible. The paper is uncoated to give it a travel guide feel and the edges are uncut. My amazing publisher, Overlapse, and I wanted to make sure to create a book that didn’t feel slick or over-produced.

The subject matter is very raw and we wanted the physical book to embody that spirit. I’m glad you described the book as “page-think full of images” because we aimed to have that feeling of urgency. If you put the book down you will notice that it won’t stay closed. The book literally won’t let the viewer put these issues aside any longer.

Feinstein: I ask this of some photographers I interview from time to time, and while this question might sound on-the-nose, I think it makes sense with you and this work. If this book were to have a soundtrack, who would be on it to guide the journey?

Willett: Here you go!

Feinstein: That works so well. I need to spend some time with it alongside the book.

We haven’t yet talked much about the specific images. One of the most heart-punching pictures, for me, which I know is not actually in the book, is the image of clenched hands on the steering wheel you shared recently on Instagram. As much as I think the word "cathartic" can be overused when describing photography, especially in the past year, it feels apt to that image. It speaks to the fears and anxieties of driving while Black in the United States. But it's also quite beautiful. The hands disappear into what feels like a sea of blue fog. It's an incredibly anxious image, but there's also this weird haze of calm....

Can you talk about the process/ ideas behind making this image?

Willett: I made that picture after the book was sent to press. I’ve continued to make images for this project and will do so for the immediate future. One thing that was really hard to come to grips with while working on this project was the fact that really almost every day there was another unarmed Black person killed while driving that I could add to the project. That was quite staggering and overwhelming. I felt a responsibility to try and honor all the people who have encountered bodily harm or emotional trauma of some kind while Driving While Black.

One of the interesting things about driving is that being in a car is in some ways a very private experience. It’s your own space, often very personalized with the decor or music you listen to and it carries the experiences and memories you’ve had while in your car. At the same time, it’s also a very public experience. There's a lot that’s been written on how it was the automobile that really brought Black private lives out into direct contact with white people and especially law-enforcement in a way never imaginable before its invention. This resulted in efforts to limit the mobility of Black Americans and created frictions in a newly shared space.

But coming back to your main question - that image was made with the above in mind. I was thinking about stories I’d heard from family and friends about how the car can feel both freeing and frightening, private and public, and often with the weight of American history blanketing the whole experience. It’s so complicated because there’s often an awareness on the part of a Black person driving about what can happen to you when you’re seemingly having this private experience in a very public space. That awareness can make you feel even more alone.

It’s also so interesting how images can defy your expectations. I’d wanted to make that image for a while but hadn’t gotten around to it. I liked the image but I was surprised by the way it seemed to cut through the noise of social media when I posted it on Instagram. The image seemed to really connect with people in a way that was meaningful. It just goes to show you that as artists and photographers we never really know what our work is going to do until we put it out in the world.

© Amani Willett

Feinstein: The release of this book comes at a pivotal point in US history. Much of white America is "waking up" (or claiming to) to racism as a fluid, contemporary reality, not just something from the history books. Not something that was "resolved" during the 60s or with the election of a Black president (and now a Black VP). A movement is bubbling, but the progress feels slow.

I’d like to be mindful of the personal nature of this question and my voice as a white interviewer asking it, but if you’re comfortable responding: how are you feeling moving into 2021? How has making this book impacted how you think of history, the present, and the future forward?

Willett: Wow. Such a complicated question for such a complicated, distressing, and emotional year. Like most people, I’m looking forward to leaving 2020 in the rearview mirror. I’m hopeful for the future if for no other reason than because without that hope the world is a tough place to be right now. I think you’re right that the winds do feel like they’re blowing in the right direction.

There’s an awareness now that having a Black president or VP cannot make up for the hundreds of years of systemic oppression our country is founded on. A new generation of civil rights leaders, while fragmented, seems to be emerging. It would be impossible to fully answer your question in this forum - we would need a week to do it justice - but I do think that images have played a pivotal role in many of the civil rights advancements that have been made throughout history and this moment is no exception.

We haven’t talked about social media yet and it’s a double-edged sword. That being said, it has nonetheless played a big role in shaping our collective consciousness around systemic racism in the last number of years. We all knew there were serious issues around racial profiling and abuse of power from the police, but images, even as we trust them less and less, still have a power that is undeniable. Throughout history we have seen that images are powerful and they are power - Frederick Douglass understood this power as he posed for more images than any other man of the 19th century.

We have also seen that people need visual evidence to grow outraged over “injustice that is perpetrated all the time outside the camera’s eye (source unknown).” This is in part what’s happened today. We can no longer avert our eyes to the horrific violence and injustices that are playing out in our social media feeds and scrolls without tuning social media out entirely. And that’s something most people are unwilling to do.

Making “A Parallel Road” has reminded me that history seems to repeat itself - there are natural cycles that occur and recede. But I also now believe that instead of history and time being a simple circle, it’s actually more of a spiral that gets a bit larger every time it repeats. I think back to the Rodney King beating in the 1990s. I was in high school and it really shook the country. It was one of those moments where the injustices we knew were theoretically out there were shown to us in all of their raw violence and hatred. That created a shift in public perception - not enough in the end, but some.

Now, with similarly heinous acts being played out on social media, the spiral has gotten larger and more people are being exposed to these violent acts than ever before. I guess the spiral could also be a snowball - it’s slowly expanding and gathering more force.

With regards to social media’s impact, it’s also important to note that while some great changes are starting to happen from the content that has been posted, it has also made Black Americans endure the psychological trauma created by viewing violence against Black bodies on a constant loop, creating another entire set of issues.

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

Feinstein: Bringing this back into the history of photography, race, and the American road, a student of mine recently shared a quote from Roy DeCarava in this 1990 interview with Ivor Miller in Callaloo Magazine, which gave me pause and see obvious parallels to your work. Not to throw to much at you, and I realize there’s probably the potential for a whole book on the subject, but I’m interested in how you respond to it/ consider it:

Excerpt from Roy DeCarava’s interview with Ivar Miller in Callaloo Magazine. See link above to read via JSTOR

Willet: There certainly is a lot to unpack in this quote and DeCarava is bringing up some really hard truths about American society. That being said, each of us has a unique way we experience and view the world. The wonderful thing about photography is that if you put ten people on the same street corner for a week with a camera the result would be ten distinct interpretations. Nevertheless, there is no doubt most Black Americans have a vastly different vision of American society than their white counterparts.

To DeCarava’s point, for him, driving around the country would arouse 400 hundred years of hardships that have shaped how he interprets his environment - a vision Frank would have no access to because he’s looking from the outside. And this is where DeCarava’s quote is most relevant to “A Parallel Road.” One of my goals with the work was to communicate the feeling of vulnerability that Black Americans constantly face as a result of America’s history. In my experience, the psychological can often inspire more empathy than facts. My book is, as DeCarava said, “ . . . Critical of America’s social values and the interpersonal relationships that grow out of those social values,” and is aligned with DeCarava’s work philosophically by aiming to puncture the surface of the images and get at something deeper.

Unfortunately, the insurrection that unfolded in Washington D.C. this past week demonstrates this idea perfectly. There are so many tragic components to what the storming of the capital revealed. It made so many of us hurt for America as we saw our democracy strained to the limit. But one of the things that has stuck with me the most was the knowledge that if it had been Black Americans storming the capital, the outcome would have been completely different. The systems of oppression that have weighed on Black Americans would have brought an unthinkable and lightening quick wave of violence and death at the hands of the police and pro-Trump “vigilantes.” One only has to look at how Black Lives Matter protesters were treated this summer to know this is true.

© Amani Willett. From A Parallel Road

© Amani Willett

Feinstein: In closing, what do you hope readers/viewers will come away with?

Willett: We live in a country where the road historically, and currently, has proven to be lethal to Black people. Like many of our cultural symbols and collective history that have left out minority perspectives, my hope is to create a project that begins a dialogue around a more complex and inclusive history of an important American experience. One that exposes the ways that minority voices have traditionally been left out of conversations about photography of many forms of art.