God and War (Inheritance). © Shane Rocheleau

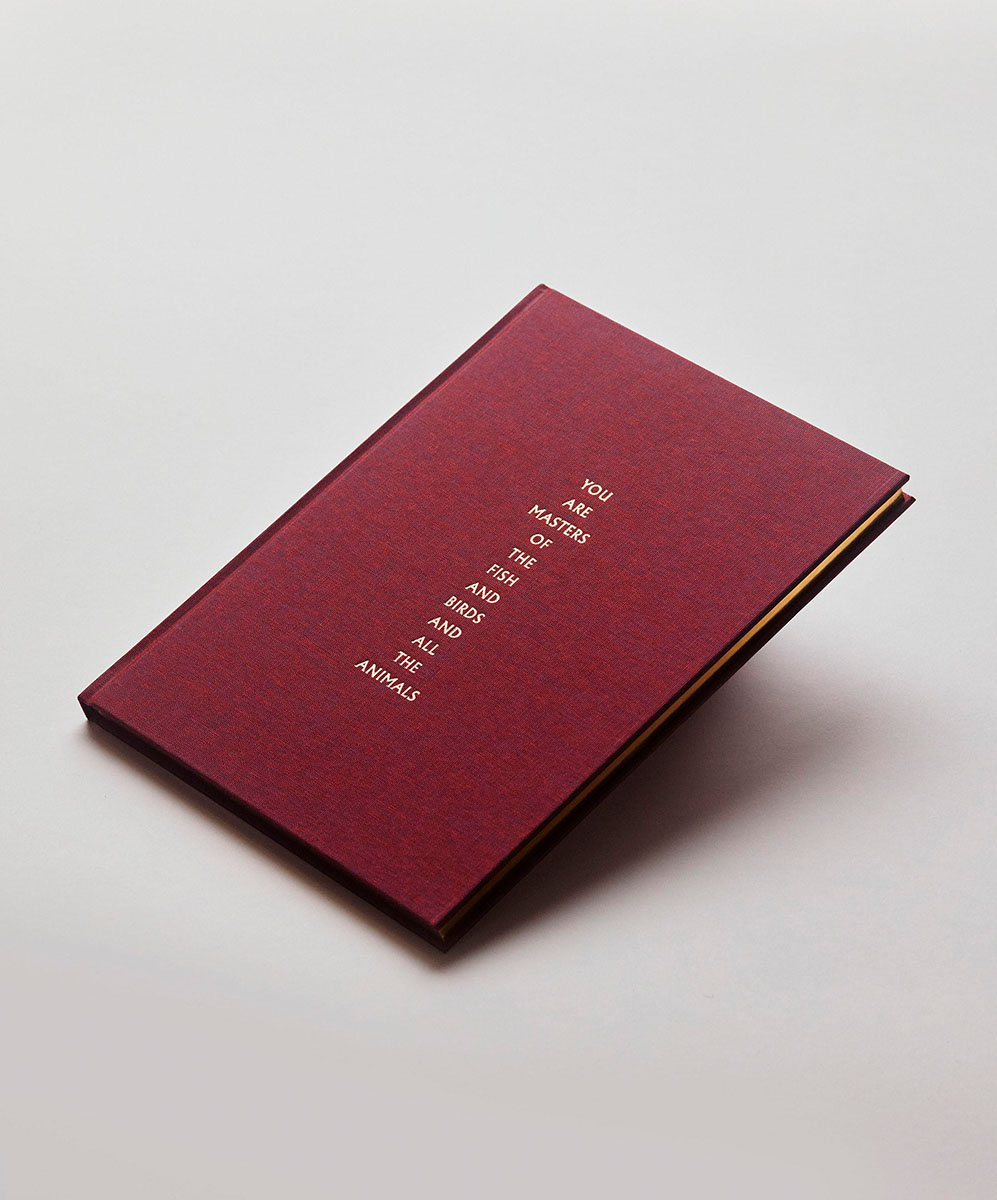

"White American masculinity is a construct," writes Shane Rocheleau about his latest book You Are Masters Of The Fish And Birds And All The Animals. "It is the subtext in detergent and power tool ads, crystallized at football games and in sermons...it undergirds our politics and religiosity, and permeates our homes. And it’s scary." Rocheleau's book, which was published by Gnomic Books earlier this year, is a collection of three years of photographs sewn into a somber, poetic meditation on the pitfalls of contemporary American male identity.

But it's not exactly what you might expect. There are no photos of fallen football heroes or fraternity bros flexing for the camera, and the photographer avoids the potential traps of incel-tinged misogyny. Instead, photographed in dim brown and red-heavy hues, YAMOTFABAATA alternates between down-trodden portraits and in between moments. Rocheleau paints an abstract portrait of weakness and uncertainty alongside countless blurry metaphors for not measuring up.

"When others look at me," he writes, "do they know that I am both the problem and the activist? I know what I’m fighting against. And I am it."

I spoke with Shane to learn more about his book and where he personally fits into it all.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Shane Rocheleau

Broken Stake. © Shane Rocheleau

Jon Feinstein: The title is a passage from Genesis in the Old Testament and ties to your disillusionment on religion. Can you elaborate on this and how it relates to the series as a whole?

Shane Rocheleau: As you know, narratives are sometimes used to justify power and supremacy, and those in the Bible are hardly exceptions. Passages such as “You are masters of the fish and birds and all the animals” have been used to justify everything from slavery and westward expansion – and the resulting slaughter – to segregation, Jim Crow, bigotry, and the maintenance of poverty. My disillusionment is with those in power and the ways they use the instruments at their disposal to maintain that power. The narrative of Christianity is just one such instrument – the American Dream is another. Those in power assuming the title of “Master” look just like me. It may sound counterintuitive, but the title signals that the work I’m trying to do is honest, inclusive, and self-aware.

Burned Cross. © Shane Rocheleau

Feinstein: This passage is also the only text that appears from the book, which gives the work a darker sense of foreboding and mystery. Why the decision to limit the text and to exclude your artist statement?

Rocheleau: One of my favorite essays is by Jacques Ranciere; it’s entitled, “The Emancipated Spectator”. He argues that a teacher should not tell a student ‘what needs to be known’; rather, a teacher should create conditions whereby a student can do what humans do quite naturally and well: explore and learn. I think the same goes for the artist/viewer relationship, so I wanted to point and tell less. I know I’m asking a lot by withholding text, but I hope this withholding creates just enough space for readers/viewers to explore and learn through their own associations and experiences. I consider the lack of text to be an invitation. And to your point, I find that sincerely facing my associations and experiences – myself – can be the most mysterious and foreboding work I ever have to do. With that said, the title list after the last picture is filled with textual breadcrumbs.

Feinstein: I love the printing of the book, especially the gold trim on the side of the pages extending from the book's spine. Is this a reference to hotel-room bibles?

Rocheleau: Thank you! That design element is Jason Koxvold’s (who did an amazing job designing YAMOTBABAATA), and I love it, too. And yes, you’re absolutely right: hotel bibles, but also missals, hymnals, and a very long history of religious texts.

Man Bending. © Shane Rocheleau

Server Wires. © Shane Rocheleau

Feinstein: I'm interested in your edit, your sense of pacing of the photos to create a blurry narrative that's somehow both understated and heavy. Photos of trees and forest landscapes volley with occasional portraits, cars, statues, photos of the sky and even tangled server wires set as chapter markers. Can you tell me a bit about the sequencing process?

Rocheleau: I think this is the part of YAMOT’s creation that is still most opaque to me. I didn’t have a set of rules. Sometimes I sequenced based on how it made me feel (My Dad followed by my chewed hand); other times, I based it on how it made me think (Musket Balls followed by a lone Homestead); sometimes I paired to create visual harmony or aesthetic contrast. Ultimately,

though, as book-printing-day drew closer, I made every final editing decision by ear, like placing

notes together. If the note grates, find a new note.

Beheaded Statue. © Shane Rocheleau

Martin. © Shane Rocheleau

Worms. © Shane Rocheleau

Feinstein: Also throughout the book are occasional images of men looking down, cracks in the sidewalk, dead worms scattered about, blank white skies and even an image of construction workers crouched in confusion over a hole – digging with no end in sight. Knowing the backstory to the larger body of work, I can't help but see these as allegories of castration and defeat.

Rocheleau: I agree with you, yes, and believe the liminal space that might result from castration and defeat to be necessary. If the narratives and symbols that preserve white male power were castrated of their power then disempowered white men might stop believing themselves entitled to power or supremacy; maybe the "Us against Them" mentality would begin to break down and more of us could work together to create a better, more inclusive country and culture. The defeat of these symbols and hierarchies would actually be a victory for most everyone, I think. But the slow cut is painful.

Untitled (Dig) © Shane Rocheleau

Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death. © Shane Rocheleau

Feinstein: You refer to "American masculinity" in your statement. What about this work makes it specifically "American"?

Rocheleau: A person could make work confronting men and their relationship to power and privilege in any culture, I’m sure. But while this is true, some of the specific symbols and contradictions I use to address male power and privilege are unique to America. Patrick Henry called for Liberty or Death in a patriarchal, revolutionary America that also enslaved millions of kidnapped persons.

Sea to Shining Sea, we sing of America the Beautiful’s Purple Mountains while in policy denying the warnings of science and putting friends of Big Oil in charge of the EPA. We celebrate the violence and bombast of American masculinity but refuse to collectively acknowledge that it’s generally dispossessed white men who commit acts of domestic mass terror. Tangibly and in the abstract, these and other very American symbols and contradictions are embedded in YAMOTFABAATA.

Fallen Tree. © Shane Rocheleau

My Dad. © Shane Rocheleau

Feinstein: Where do you fit into all of this personally? What was your experience like growing up? What compelled you to make work about the fragility of American masculinity?

Rocheleau: I grew up in a very nice middle-class home on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. I loved sports and was a smart but mediocre student. I came from a long line of military men and admired each and every one of them. I went to church; indeed, we were family of the year one year at our Catholic Church. But while I thought I should’ve, I never really felt like I fit in, anywhere. And I think that benefitted me. It gave me critical distance more difficult to attain had I fit in. I think I spent my time both wishing I fit in AND looking at the pitfalls of the construct into which I wished to fit.

Being a fairly athletic, smart, white boy from New England, certain things were expected of me –not least of which through the vague idea that I may make my male military lineage proud; but, I think I had the critical distance to appreciate that I didn’t want to be the cliché of a white American male. I still don’t always succeed, but I believe it to be a good and honest task to resist this expectation. This book embodies both my resistance and my failure to resist, yet more contradiction.

Site of the Death of Edward Jones. © Shane Rocheleau

Storm. © Shane Rocheleau

Feinstein: There's something musical about this book. One of my favorite questions to ask photographers is: if this work had a soundtrack or accompanying mixtape, who would be on it?

Rocheleau: I love this question. Okay, in no particular order: Sleight Of Hand by Pearl Jam; I Offered It Up To The Stars And Night Sky by Dirty Three; Paranoid Android by Radiohead; Tom Traubert’s Blues “Waltzing Matilda” (gotta be a live version!) by Tom Waits; Fade Into You by Mazzy Star; Comfortably Numb by Pink Floyd; Suzanne by Leonard Cohen; Enjoy The Silence by Depeche Mode; and, Go Your Own Way by Fleetwood Mac. These are all aspirational: if only I could make something as beautiful as any of ‘em!

Feinstein: Does this work feel complete at this point? Are you continuing to make pictures for it?

Rocheleau: So often ends feel more like arbitrary stopping points. And while I’m unlikely to add to

YAMOTFABAATA, my newest (and incomplete) work arises directly out of the lessons YAMOT

taught me about my own – and my culture’s – psychological inheritance. So I guess the answer

is yes and no. I could say this about all my work. I’ve finished many projects but the project

never seems done. There’s a rope holding all of it together.