In Honor of Syrian Refugees © Azin Seraj

Azin Seraj is an Iranian-Canadian artist currently based in northern California. Her research-based practice – driven by video, photography, and lush installations that combine visual and sonic elements – addresses socio-political concerns through a transnational lens.

In mid-2018, I collaborated with San Francisco-based curator and educator Dr. Kathy Zarur to include Seraj’s project Concurrency in the our exhibition Betweenscapes. Zarur and I spoke with Seraj about her work and social practice methodologies that help support communities and activist networks as they strive for concrete change.

Roula Seikaly and Dr. Kathy Zarur in conversation with Azin Seraj

Roula Seikaly: How do you describe your practice?

Azin Seraj: Versatile. I consider myself an interdisciplinary artist. More and more, I find that the work proceeds from an idea and not the form it will take. Though video is my primary format, photography has always been a part of my practice. I'm also working with social practice and installation as a means of conveying ideas.

Seikaly: Has social practice been a driving force throughout your work?

Seraj: It's a more recent approach. There are a lot of social practice projects that emerged in the last decade, and the term "social practice" has always been charged for me, particularly the way some artists use it. I want what I produce to have a tangible and positive outcome for the communities I work with.

Kathy Zarur: So often, social practice projects end up crediting the single artist or author, and not the community they work with. I think that what you're doing with Chroma Collective, a group of UC Berkeley alumni, at Artist Television Access and other spaces is a beautiful way to produce collaboratively. Could you speak to those projects as a part of your creative social practice?

Seraj: That's a great example. I see myself as an educator, artist, and activist, and I feel like all three inform my identity. Being a mentor, and working with mentees, is really important to what I do. I benefited from working with mentors, and I want to leverage my privileges and resources to benefit those I work with.

In Honor of Farkhunda Malikzada © Azin Seraj

Seikaly: I came to know you and your work through the Concurrency series. Could you describe that project?

Seraj: That project incubated for a long time before I started it. Growing up in Iran, I was an avid collector of banknotes. In our culture, there are many rituals involving legal tender, such as giving signed fresh bills as a sign of prosperity. Instead of spending them, I would keep them. I have notes that my mother and grandmother signed. So, I was interested in bank notes at an early age and as I got older, I was interested in what's depicted on the notes.

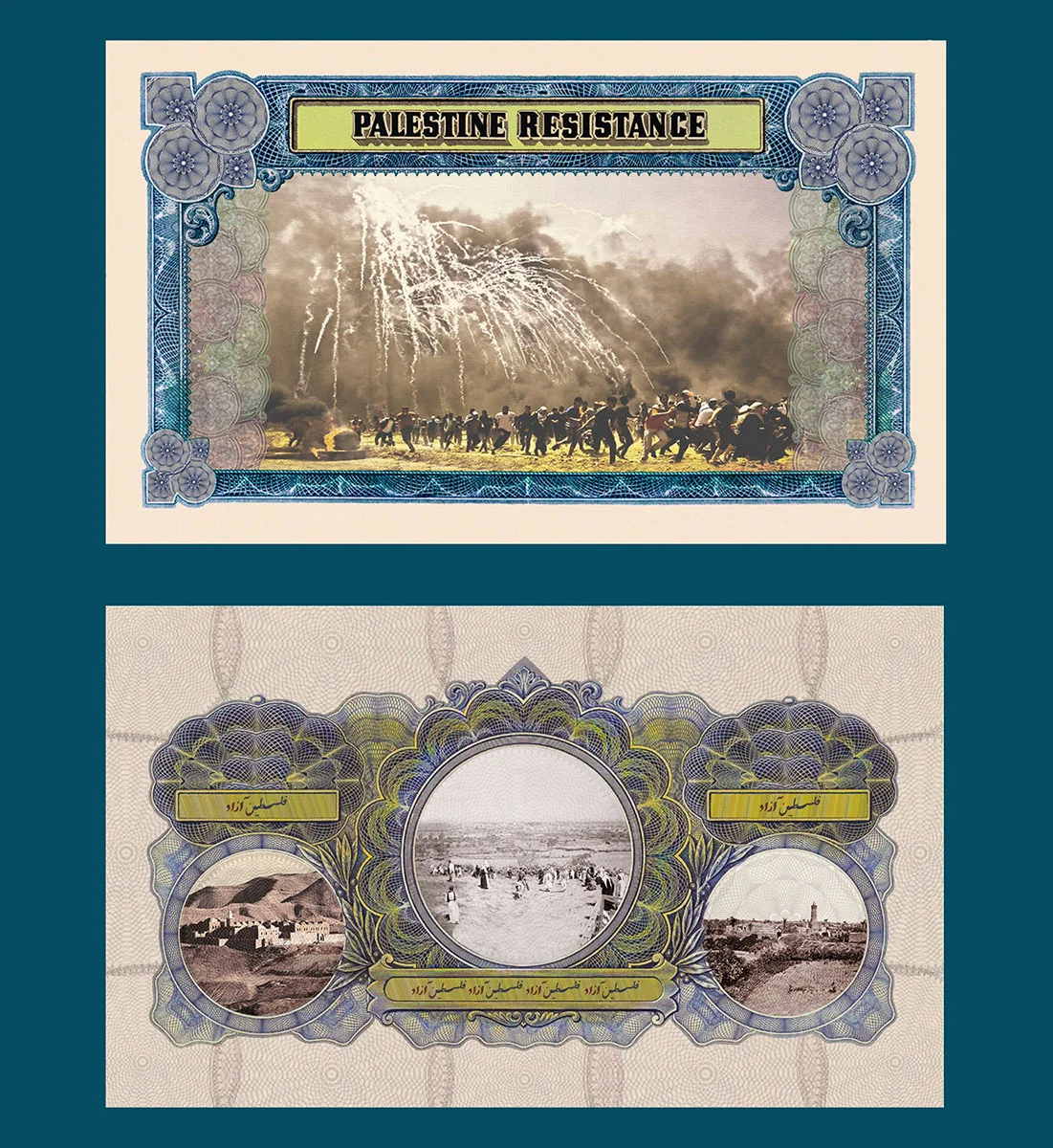

As I look at them more closely, through a critical and aesthetic lens, I think about the messages they convey symbolically and what these objects mean when an economy is completely devalued, as happened in Iran. I think about Iranian currency produced before and after the 1979 Revolution, and how the different regimes represent themselves through currency. National identity is wrapped up in patriarchy, commercialism, nationalism, history, religion, and the wider colonialist project in the Middle East.

Seikaly: Do you see these objects circulating, so to speak, as legal tender does? Is there a long term desire to see them transit through various collections, or enter the world?

Seraj: That's something I think about often. It depends on funds, as all creative projects do. I would love to expand their presentation. To me, one of the main draws is the tactile experience of legal tender; to touch and feel it and enjoy that intimacy is important. As the project stands now, they are preserved in such a way that they can't be touched. I love the idea of working with certain venues to create opportunities for active engagement with the bills.

Installation view from Betweenscapes exhibition

Zarur: On a conceptual level, they do have a different life. You donate one half of the sales to nonprofits that work with groups featured in the project. Can we talk about that?

Seraj: Absolutely. That idea emerged from a conversation with a friend of mine. I was thinking about notions of agency, and who I propose to speak for through this project. It's all good intentions, of course, to highlight voices of resistance or different ongoing events, but at the same time I want to be careful of my position as an artist. I want this work to benefit community, not simply highlight the artist's role exclusively. Beyond education, I want this work to benefit organizations that are helping those featured on the bills. That was an important learning experience for me.

Zarur: How did the project shift from depicting Iranian national identity to a focus on worldwide resistance?

Seraj: It emerged from sitting with overwhelming anxiety brought on by consuming media, and feeling powerless before world events. The countries reflected in the bills are, in one way or another, in conflict with US national interests. We don't hear the details, for example, about the war in Yemen or the consequences for those living through it. We don't hear about what's going on in Iraq; who is rebuilding and governing the country now? What's going on in Afghanistan regarding women's rights?

As an artist, I felt I need to channel that energy instead of absorbing all the negativity. I want to highlight the stories that don't get enough attention, and challenge the breakneck pace of media in reporting events. I want to create something contemplative, and learn more about these important stories. I want to go beyond reflecting the hardship and report on the larger cultural context. What does it mean to depict the world's oldest skyscraper, which was built in Yemen? From a western media perspective, we only see these countries under the worst circumstances. I want to go deeper than that, and resist the urge to otherize these cultures.

In Honor of Earthquake Victims And Survivors of Kermanshah Iran © Azin Seraj

In Honor of Ahed Tamimi © Azin Seraj

Seikaly: How do you source the images you use?

Seraj: They are a combination of existing banknotes from a given country and media images. I work with images of activists, often who died supporting resistance causes. I try to get in touch with the photographer who captured the image, and if I can't contact them, make sure to credit them. That's very important to me.

Seikaly: What do you do, in terms of self care, to make space for these ongoing traumas and not lose yourself in the process?

Seraj: The citizen activists I highlight have left a mark on history in some way. It's important to me artistically to embrace what they went through, as horrifying as the details are, and understand as much as I can what they sacrificed. I thought it would be disrespectful to make work about their lives, but not know fully the terms of their deaths.

Zarur: I'm thinking about the question of self care, and how trauma and loss play out all over the world and what resources and privileges we marshal to manage it all. It's all held alongside happiness and joy. I don't think it's an either/or situation. We don't make room for challenges, broadly speaking. In contrast, you doing this work is more holistic way of being in this world. Your practice, and the Concurrency series specifically, offers an example to artists and others who may be overwhelmed by what media transmits to keep things in perspective.

In Honor of Palestinian Resistance © Azin Seraj

Seraj: Definitely. This project is heavy, but it also allows me to learn and expand the love I feel for these communities. That's vitally important through all of this.

Zarur: What are you working on, and what’s on the horizon for you?

Seraj: My collaborator Lydia Greer and I founded a media company. Our first project is a documentary piece about artist Robin Frohardt and her project The Plastic Bag Store. I'm also producing a new video work entitled Synchronous, which explores the causal relationships of human consciousness on a subconscious level.

I was also recently chosen for Southern Exposure's (SoEx) Curatorial Council, which is a rotating group of eight artists and two staff members that select artists to develop and present new ideas at SoEx. It's a highly competitive process, and I'm honored to be a part of it.