Clear Perplexities from the series “ Aqueous” © Elina Ruka

Artist’s first Philadelphia solo show examines water’s power to both attract and push away.

On October 5th, Latvian artist Elina Ruka’s solo show “Immersion” opens at Philadelphia’s Gravy Studio and Gallery, marking her first solo show in the city. The recipient of an MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago, Ruka uses numerous media, including photography, installation, video, and sound, to create tranquil and curious works of art. Addressing themes ranging from her impressions of the United States, her memories of Latvian life, and the never-ending mystery and mutability of water, Ruka’s art is both highly emotive beneath the smooth surface, creating an irresistible tension between what we show off and what we choose to keep hidden. Deborah Krieger speaks with the artist in advance of her opening.

Deborah Krieger in conversation with Elina Ruka

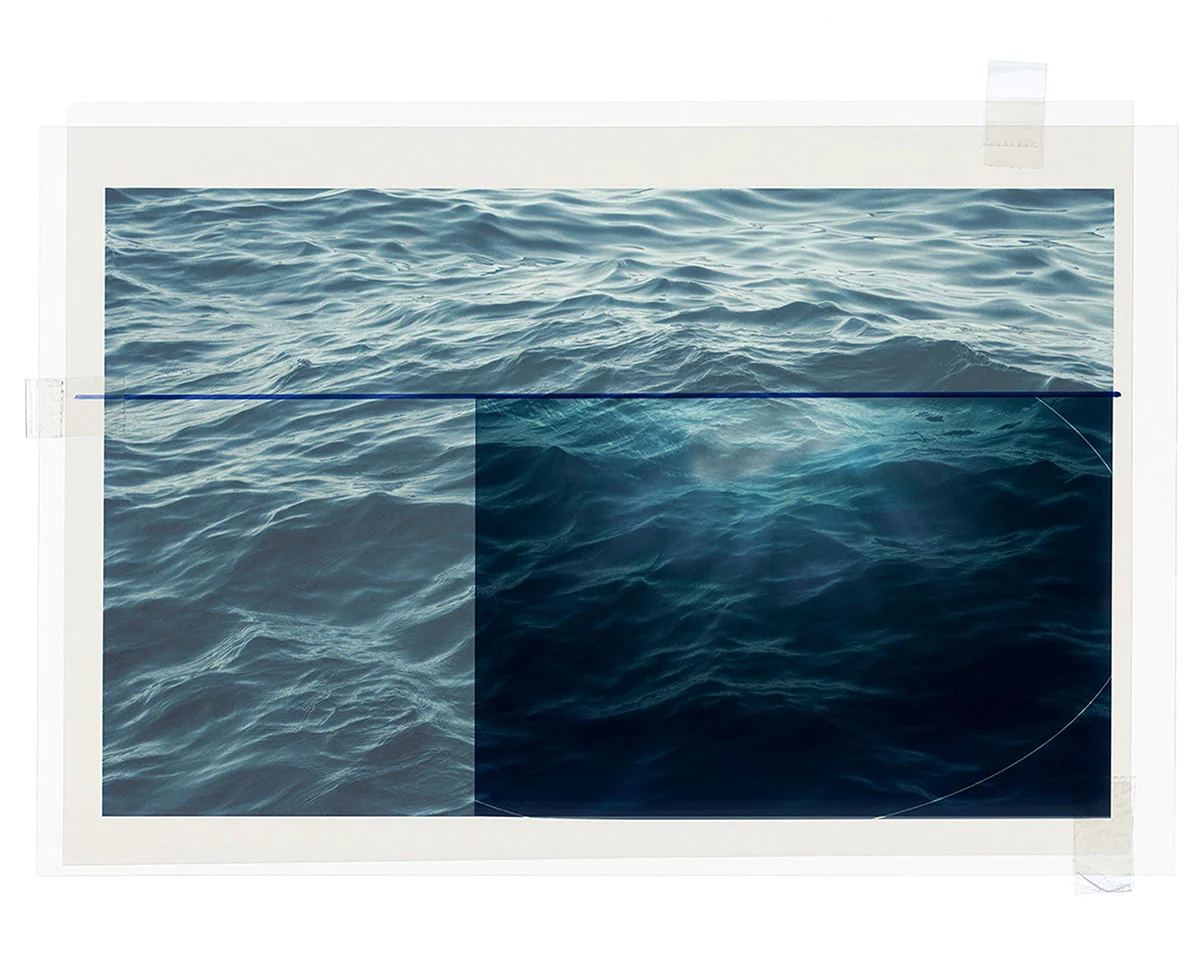

Underneath: Blue Line from the series “Aqueous” by © Elina Ruka

Deborah Krieger: How did you get involved in the upcoming Gravy show?

Elina Ruka: Krista Svalbonas, a Gravy member, invited me. We met at Columbia College Chicago, where she was a faculty member and I was studying in the MFA program. I respect her work a lot; Krista has always supported me and my art, so we kept in touch. She previously invited me to a group show at the Global Center for Latvian Art in Cesis, Latvia, that pairs one Latvian and one diaspora Latvian artist in an exhibition of 70 artists.

Krieger: What works will you be showing?

Ruka: For “Immersion,” [my show] at Gravy Studio, I am showing work from the series “Aqueous.” I like creating new work for every show, but sometimes I add a piece or a couple from the existing ones. There will be both [old and new work] at this show, but none of the pieces for “Immersion” have been shown in America before. It has been an effortless process to work with Gravy. I am excited, and I am looking forward seeing the show in their space.

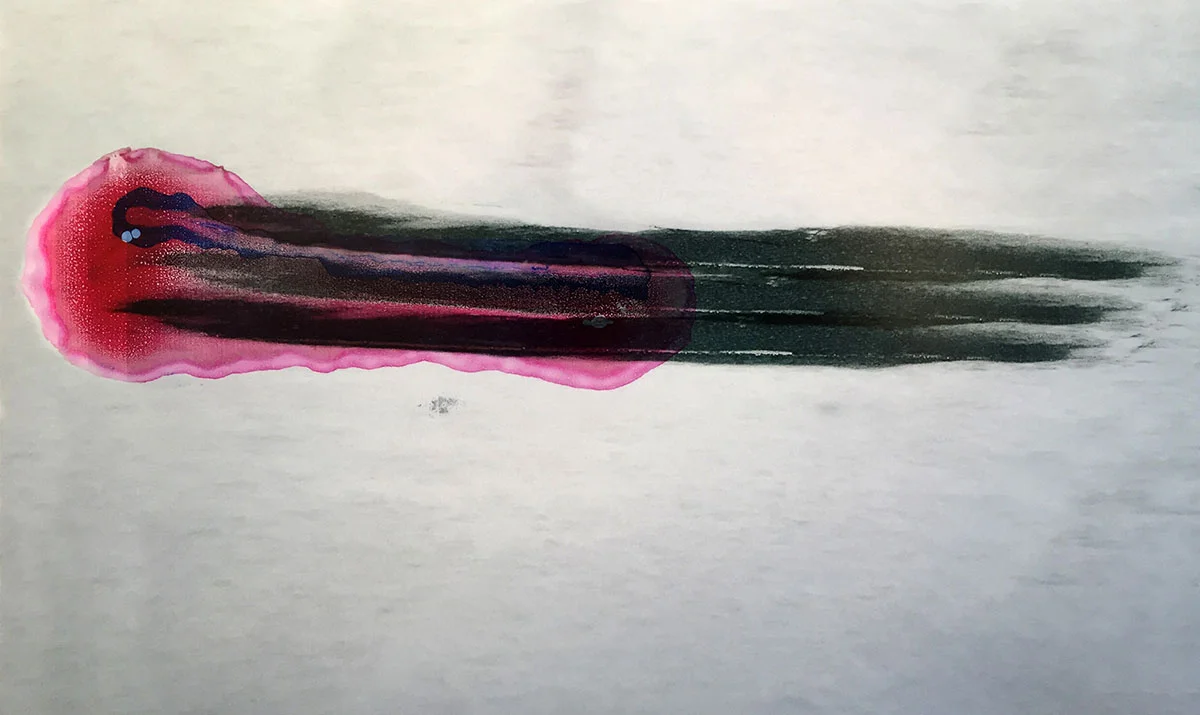

C4 from the series “Ambiguous Research at Seven Possible Seas” © Elina Ruka

Installation of Decalage Horraire from Elina Ruka’s exhibition Immersion at Gravy Gallery and Studio

Krieger: You began your Lessons in America sound pieces in 2014. How have you noticed your observations about the United States changing as you’ve continued to live and work here?

Ruka: The beginning of this sound work [came] during a class I took in the Interdisciplinary Arts department [at Columbia College Chicago]. It was a certain experimentation with a new discipline, and also a way to adjust to living in America, to a different culture and thinking, and to being in graduate school. Now, after almost five years in the US, I have moved back to Latvia. It will be interesting to continue working on these pieces because with the distance, I definitely have gained perspective. I hope this work will be exhibited in the US.

Krieger: What artists/teachers/mentors have inspired your work?

Ruka: There are a lot of artists that inspire me. I can only name a few of them. Sophie Calle, Rinko Kawauchi, Liz Deschenes, Mark Rothko, Broomberg & Chanarin, Starn Brothers, James Turrell, Richard Serra, and Ann Hamilton have been longtime inspirations. I also admire Chicago artists Barbara Kasten, Barbara Crane, and Aimee Beaubien.

Kelli Connell and Ross Sawyers were my advisors in graduate school. I always felt their support and nourishment, and it helped me to grow as an artist. During meetings with Kelli to discuss my work, [for example,] instead of giving me a review, she would give me questions that I had to answer for myself about my work. Now I always have a notebook with me, and I usually create first with writing.

Ross inspired me with his work ethic; he does something for his art every day--be it writing, thinking or making. That really impressed me, and I have adopted this practice. It’s not always about creating a masterpiece a day; it’s hard work, research, a never-ending applications process and accepting that rejection, as painful it might be, is part of it. I am grateful for having met great artists in Chicago who have been my mentors and friends. Colleen Plumb has helped me with her experience in the field, and has inspired me as a person and artist. Clarissa Bonet, Julie Weber, and Whit Forrester, also graduates from the Columbia College MFA program, have been wonderful peers. I was part of two artist collectives, feeling the trust and support when needed.

© Elina Ruka - installation view

Installation view from Immersion at Gravy Gallery and Studio

Krieger: You primarily studied photography, so what led to your decisions to branch out into working with video and sound?

Ruka: I came into my masters in photography with a traditional view on art and photography. After I started working on the series “Aqueous,” I understood how limiting this view and medium itself were, so I began experimenting with different media to find better expressions for my ideas.

I still feel the most at ease in photography, but I expanded my practice. I have some ideas I see fitting within sculpture/installation, some within video or sound. Taking a class in sound not only broadened my understanding of music in general and enriched my knowledge and experience, but also expanded my idea of what I would like to make. When I work with video, I can make my own sound for it. I like this freedom. Next, I want to make large-scale outdoor installations that will be accompanied with sound. Every challenge is an opportunity to learn something new.

Krieger: Your earlier photographic series, such as Domesticities and A La Recherche d’Elan[sic], are primarily figurative, yet your recent series like Ambiguous Research, and especially Aqueous, use much a more abstract visual language. Why the change?

Ruka: I don’t think an artist has to only work in one style or field. We are complicated as human beings are; we change and evolve all the time, so a certain transition is natural. My earlier work was made reflecting the mindset and worldviews I had at the time. The complexity and multi-layering is an important part of my work right now.

The subject of water is extensive. There are numerous aspects I am still discovering, and I cannot tell just yet what form and style they will take. If there is one thing I have learned from my themes, it’s to go with the flow and to trust my creative process. Layering in my work is both physical and conceptual. I work on water’s properties by using transparent material, layering images, cutting and organizing them in the space.

“Immersion” is also about the need to look closer, deeper, with more attention. We are presented with so much information that a lot of details escape our conscious processing.

B7 from the series “Ambiguous Research at Seven Impossible Seas” © Elina Ruka

B2 from the series “Ambiguous Research at Seven Impossible Seas” © Elina Ruka

Krieger: The color in your photography is beautiful. Have you ever considered working in black-and-white?

Ruka:I have worked in black-and-white, which every photographer starts with. Color in [my] work is an expression of my interest with water: it represents fear, longing, fascination. The color spectrum that is perceived through water changes with depth. I don’t think I could express any of these [ideas] in black-and-white imagery.

Krieger: Your work demonstrates an affinity for water and a sense of awe at the mystery of the oceans. What are some of your favorite works of art that deal with or are about bodies of water?

Ruka: Roni Horn[’s works about water]; ocean drawings by Vija Celmins; “Seascapes” by Hiroshi Sugimoto; works by Olafur Eliasson, particularly “Your waste of time” and “Deep ocean void;” “Littoral Drift” by Meghann Riepenhoff; “De Profundis” by Miguel Rothschild, and many more.

Boundless © Elina Ruka

Krieger: Your series Ambiguous Research at Seven Impossible Seas is explicitly about creating unreal, non-existent sea creatures. Can you talk about how you negotiate the idea of photography as “real” with using that medium to be fantastical and creative and imaginative?

Ruka: What is reality? In recent research about the human mind, scientists have concluded that reality is what our brain creates; it is real because we believe it is real.

For me, photography is a tool to create art. I take photographs to make images; it is not about depicting what is in front of me, it is giving a physical shell to what is within me. I created “Ambiguous Research at Seven Impossible Seas” as my response to the deep ocean still being a mysterious place. New species are being discovered and living things are found deeper and deeper in the ocean where they believed no life could exist, so this series is my interpretation of what else could be found within the depths of the oceans.

“Aqueous” also started off with my interest in water, so [those works] are an interpretation of my research and reality more than a reproduction of the real world. To me, even a documentary is not “real” because it is made by someone and is thus interpreted. Even an observation of a subject changes it.

Kristians from the series “Domesticities” © Elina Ruka

Grandfather’s Slides from the series “Domesticities” © Elina Ruka

Krieger: There are some images in your Domesticities series that are very specific to Latvia, and yet there are others, like the boy with the plastic dart gun, that seem like they could have been made in the United States. How do you work to make sure that you don’t risk essentializing a kind of finite, bounded idea of Latvia while also making images that seem universal and relatable?

Ruka: My main goal was to show how I feel about Latvia [and] our traditions and identity through a personal prism rather than to create an official, representational image of Latvia. When it comes to art, I think there is a certain sensibility that allows us to relate, even though we are not part of that particular community or familiar with specific history.

Love, grief, joy, attachment, [and] pride are emotions everyone can relate to, regardless of nationality and background. If I can transfer some emotion or have the viewer react when looking at my work, I have done my job.

Gravy Studio and Gallery is located at 910 N. 2nd Street, Philadelphia PA 19123. The opening for “Immersion” will be held on October 5 from 6-10pm.