© Lauren Silberman. From the series The Opposite of Salt

Lauren Silberman has been photographing communities and subcultures in New York City, its outer boroughs, and across the United States for nearly two decades. While technically “documentary,” her work is full of narrative and metaphor, and often is more enigmatic than the straightforward reportage one might expect. I recently had the opportunity to dig into her work when selecting her as a finalist for the juried exhibition American Splendour at New York City’s Iloni Art Gallery this past summer.

Her latest series, The Opposite of Salt is Water, which opens this Friday at Calico Brooklyn in Brooklyn, NY pushes this further, with a new sense of magical ambiguity. Photographing in Amboy, an unincorporated community in San Bernardino County, in California's Mojave Desert, Silberman uses images from the region to represent symbols of ideology and mythology associated with the evolution of the American dream.

In advance of her new exhibition, I emailed Silberman to learn more about her work.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Lauren Silberman

© Lauren Silberman. From the series Party Science.

Jon Feinstein: What first drew you to photography?

Lauren Silberman: Photography has always provided a way for me to participate in events that inspire me as well as a way for me to connect with other people. In the beginning of my career as a photographer in the early 2000s, I found myself going to events in warehouses in Brooklyn, photographing a community of new people who took an active role in creating their experiences for their own sake. I participated in these events and found myself running through the streets of Gowanus with life-size bull puppets and mariachi bands, giant food fights in the middle of Dumbo with 200 other people dressed in Tyvec suits, and all night parties in basements and lofts with art covering every inch of the space.

Much of it was ridiculous and indulgent, but it wasn’t happening anywhere else, every experience was completely different from the one before, and it was always thrilling. We were not subscribing to popular culture, but creating our own and photographing these events was my way of experiencing them. I guess you could say I was totally obsessed with the people I was surrounding myself with and I was enamored by the events we were going to -- photography was how I indulged that obsession.

© Lauren Silberman. From the series Afterparty.

Feinstein: Do you consider yourself to be a "documentary" photographer? Does that even matter?

Silberman: I am interested in how the human condition expresses itself. I have been lucky enough to find amazing communities wherever I go – all of them interwoven through people I’ve met in the place before. My work is an expression of my interest in how people create and find meaning in their lives – through their work, through their relationships, through their hobbies, and through the places they inhabit. I don’t think that title is really relevant to the work that I make, but I have always been interested in real people. Sometimes I throw a little twist on it so saying I’m a documentarian would be doing a disservice to my subjects.

© Lauren Silberman. From Portraits

Feinstein: Project to project, has your approach to photography changed over the years? If so, how, and what was the most dramatic/ remarkable / "a ha" moment of change for you?

Silberman: I don’t think my approach has changed drastically, but I have constantly had to remind myself to go back to the looking. I think if there was an “a ha” moment, it came during the switch from film to digital – I used to shoot a lot with a Mamiya 7, which is a rangefinder and forced me to work slowly. The slower process to focus plus the limits of film (limited exposures and budget) always worked to my advantage in that I had to be very intentional in how I made a photograph.

The freedom that opened up with digital was liberating. Finding the balance between feeling that freedom while also keeping an intention has been challenging but really important. I think it all just comes back to really looking and to the relationship with the subject. For that reason I have been going back to film more recently as it forces me to slow down.

© Lauren Silberman. From the series Afterparty

© Lauren Silberman. From the series Gold Dust/ NOLA

Feinstein: Especially with this kind of work, I’m consistently fascinated with how photographers are influenced my other photographers. Who are some of your photographic heroes, “then and now?”

Silberman: Then: Nan Goldin was my first photographic love. I saw a show of hers when I was visiting Amsterdam while still in college, before I ever seriously picked up a camera. I was floored by the immediacy and intimacy of her work and it stayed with me. I returned to her work often, especially in the first few years of photographing.

And I also fell in love with the work of William Eggleston. His mastery of color is undeniable and his ability to identify the extraordinary in the ordinary has always been an inspiration to me.

Now: I have followed the work of Autumn DeWilde for a few years now. I think she is one of the most talented commercial photographers working now. Her work is just beautiful. It’s intimate and real and I love the connection she has to her subjects. She also has a great talent for using photography in really different ways, whether she is shooting snapshots or working in a more staged and art directed way.

I have also been loving the work of Genevieve Gaignard, whose work I recently saw at the Flag Art Foundation in NYC. She uses self-portraiture, installation, and collage to express her ideas. Her work has a sense of humor and is also really technically strong. She’s addressing ideas of identity in her work, and that has always interested me.

© Lauren Silberman. From the series Gold Dust/ NOLA

Feinstein: I can definitely see that in a lot of your work. I wasn’t previously familiar with Gaignard’s work, but I plan on diving in! Back to your own work, so much of it is about community and identity – how subcultures and other aspects of culture influence identity….

Silberman: I am driven by curiosity, by fascination, and, at the risk of sounding earnest, by love for my subjects. Diane Arbus once said “for me the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture,” and I have to say I relate to this. I photograph the people, the places and the things that I love.

When I began my project on the Black Label Bicycle Club, I was totally obsessed but also intimidated by the members of the Club. I was nervous about them feeling comfortable with me, accepting me, and ultimately letting me photograph them. But I have always liked being out of my comfort zone, which is what drove me to pursue the project. Of course, everyone I met in the club ended up being wonderful and fun to work with. And I think it shows in the photographs. One of the best compliments/critiques I ever got about the work was when a fellow artist said that he felt like I really loved the people in the images, and that was amazing to hear; it meant that something was coming through in the work. I love my subjects and if that comes through, then the work is successful. I couldn’t make this work if I wasn’t a little obsessed or in love and I think that that sincerity is so important.

But to get back to the question, I guess part of my interest in some of the subcultures I have photographed is that they are part of something outside of myself, and photographing them was just a way for me to understand them and their connection to each other - my curiosity leads to the exploration which ideally leads to an inspired collaboration. When I photograph a person or a group of people, I am interested in how they identify themselves through the choices that they make and how they present themselves to the world. The aesthetic choices they make, through dress, through the spaces they inhabit, etc. are all choices that define one’s identity. So ultimately, I’m interested in how people express their identity.

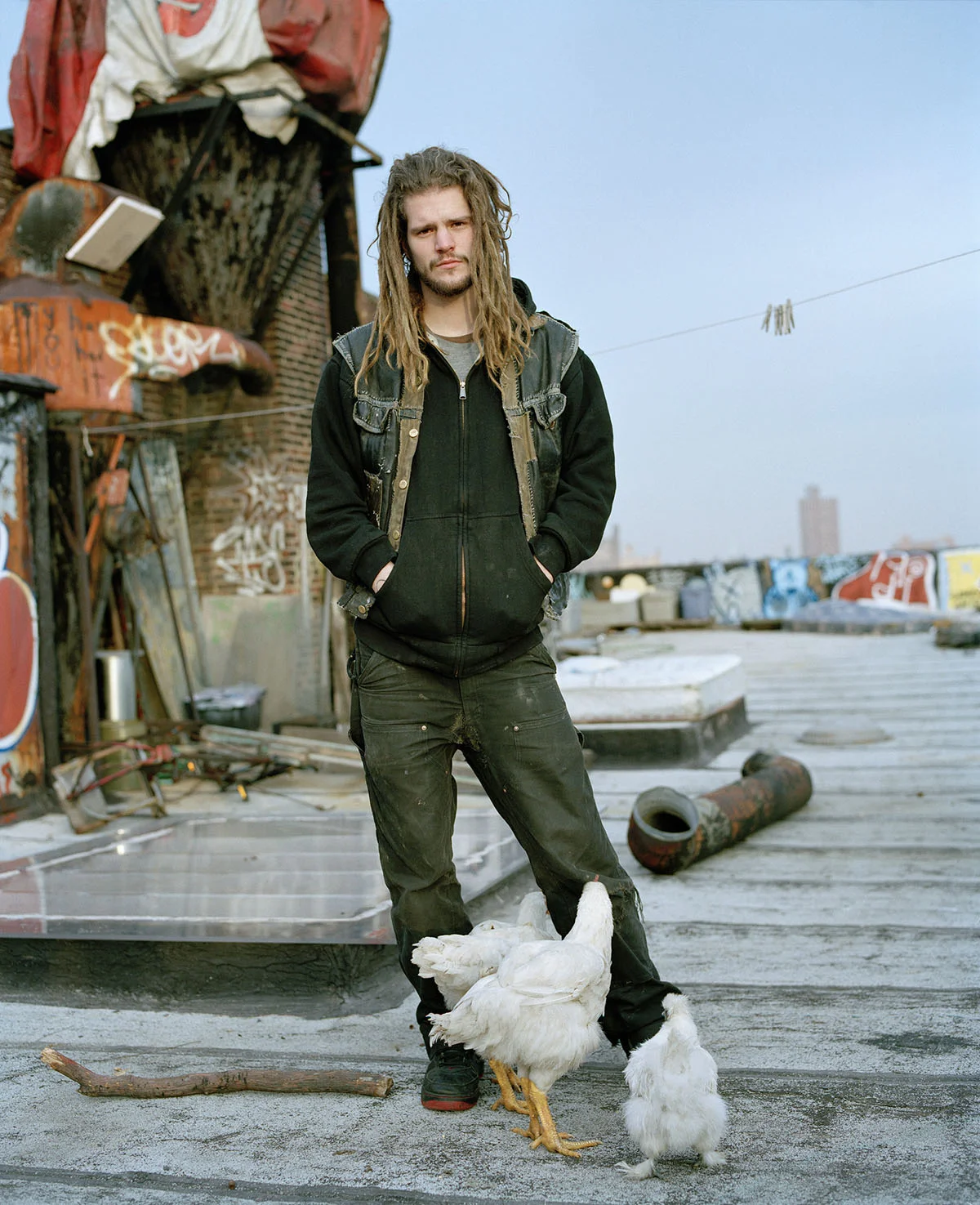

© Lauren Silberman. From the series The Black Label Bike Club

© Lauren Silberman. From the series The Black Label Bike Club

© Lauren Silberman. From the series The Black Label Bike Club

Feinstein: You mention "tension" and "disorder" throughout your written statements about your work.

I think there is something really interesting to be found in the in-between and left behind. My Afterparty series is very much about that. The series of images are of abandoned, makeshift party spaces in Brooklyn, taken between 2006 and 2013. I had a personal connection to the events and the parties that were held in these spaces, and I wanted to make something more than party photos. The spaces were always totally DIY and total labors of love and I wanted to look more closely at that, so photographing the interiors made sense.

I decided to make the photographs as soon as the parties were over, when they were empty and trashed. The final images are of these totally crazy interiors with wild decorations and bottles and cups everywhere; there’s evidence of a party, but no party to be seen. The final image is a collaboration between the organizers of the party, the attendees and myself. The viewer is, in a way, invited to the party…but they missed it. It’s here that there is tension - a lush, rich, and colorful photograph, but it’s of a dirty and abandoned space. There’s a contradiction in what you are looking at and I find that really interesting. I am trying to find that strange place in all my work - it’s not always there but I that’s why I keep doing it!

© Lauren Silberman. From the series Afterparty

© Lauren Silberman. From the series The Opposite of Salt

© Lauren Silberman. From the series The Opposite of Salt

Feinstein: Can you tell me about your upcoming exhibition The Opposite of Salt?

Silberman: Yes! I made the work while on residency in California. I fell in love with the town of Amboy, which is a small, mostly abandoned town (technically it’s an unincorporated community) on a less traveled stretch of Route 66 while exploring the area beyond Joshua Tree.

The show is an extension of my fascination with detritus but in a slightly more abstract way. It’s kind of about this detritus of a dream, specifically the American Dream. It’s about what the dream of America is and was and how it has failed in this specific place. There is no running fresh water in Amboy; only salt water comes out of the taps. Amboy is an absolutely beautiful and strange place that I couldn’t resist learning more about and photographing. There isn’t actually much there (kind of like in the Afterparty photos) but that’s probably why I was drawn to it…trying to find the beauty in this melancholy place.

© Lauren Silberman. From the series The Opposite of Salt

Jon Feinstein: Sadly, I won’t be able to make it to the exhibition, but it sounds exciting, and I’m hoping some of our readers check it out. Final question: If you could define your practice in a tweet, what would it be?

Seeking beauty in detritus.