Referee Module Interior © David Maisel. Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery

“Not now.”

That was the reply to photographer David Maisel’s 2004 request to document Dugway Proving Ground. Rather than interpret the response as a dodge or definitive “no,” Maisel was was heartened, and began a decade of carefully-phrased communication with contacts in and outside of the Department of Defense, intensive vetting and, finally, permission to photograph a military installation so closely guarded that all but a few both in and outside the state of Utah know what goes on there.

Proving Ground, Maisel’s latest installment in a career-long photographic examination of the landscape, up through Feb 24th, 2018 at Haines Gallery in San Francisco reaffirms that the answers we seek through access are often incomplete.

Exhibition review by Roula Seikaly

KYDOIMOS Video still © David Maisel. Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery

Located 85 miles southwest of Salt Lake City in the Great Salt Lake Desert, Dugway Proving Ground (DPG) was commissioned in 1942 and confirmed as a permanent military installation in 1954. Over the course of seven decades, it has been the nation’s primary site for chemical and biological weapons testing. For some Utah residents, it is a point of patriotic pride, a demonstration of all that is normal, red-blooded and American against the foil of oddity that Church of Latter Day Saints practices and beliefs suggest. For others, it is dreaded and represents the worst of contemporary non-nuclear warfare preparation. Somewhere between those extreme ideological points, an uneasy balance has been struck.

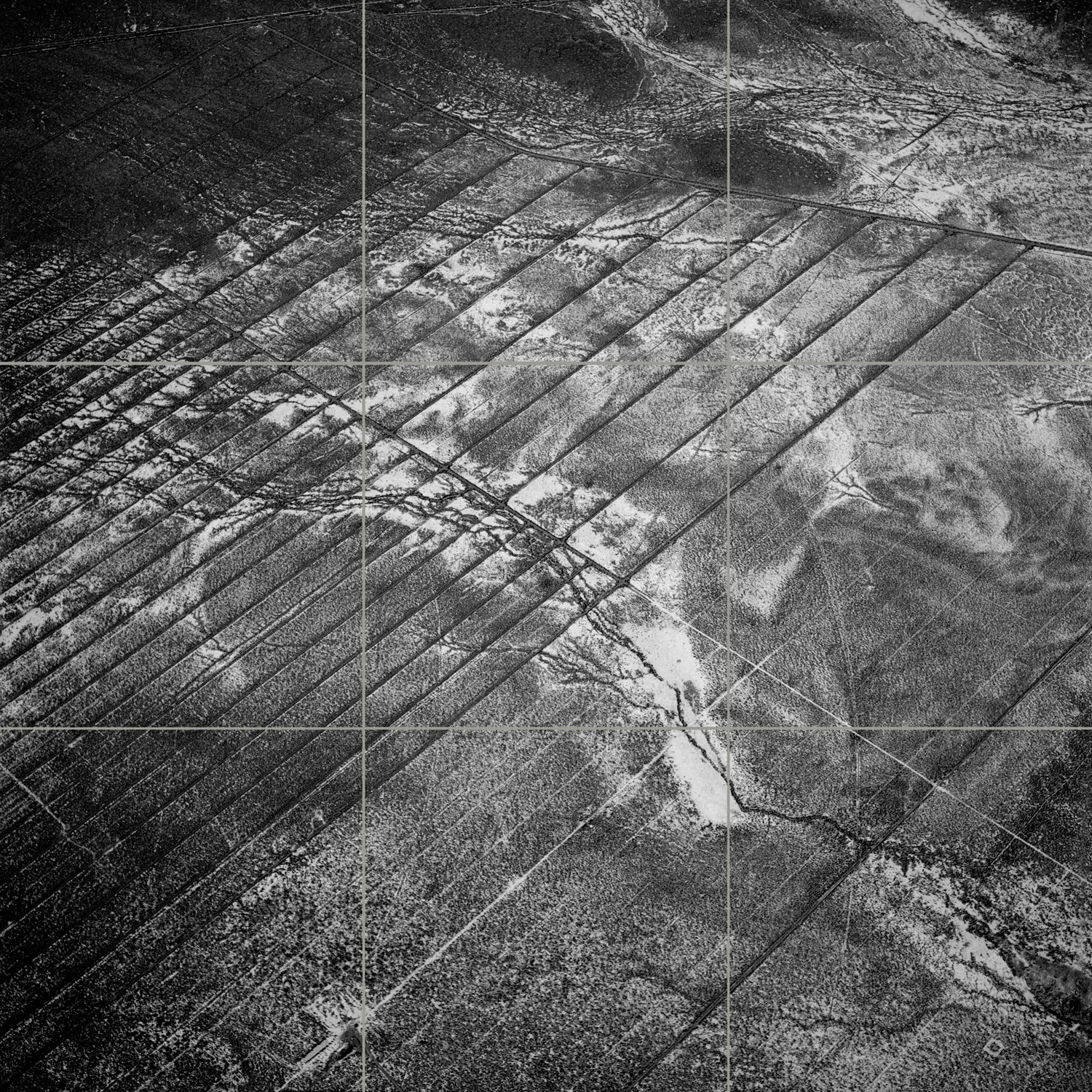

Air Force Target Grid Building © David Maisel. Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery

Access and denial are inextricably woven themes that inform Proving Ground. Presented in the gallery’s anterior space and media room, the installation reveals the locations in and around the site to which Maisel was permitted. The spartan presentation provides, at best, a tantalizing sample that stirs a desire to know more and mirrors Maisel’s own circumscribed experience at the base. On one wall, the six-image sequence Air Force Target Grid Building (2014) highlights an unremarkable structure conspicuously situated on the scrubby desert floor presented from different angles. Expertly composed and aesthetically pleasing as individual and grouped images, the sequence reveals little more than the building’s existence in the stark desert landscape. An open door, visible in five of the six images suggests permission, or liberties that neither the photographer nor we as viewers are allowed.

Proving Ground Installation photograph. Courtesy of Haines Gallery and David Maisel. Photo by Robert Divers Herrick.

The clip above (please allow a few seconds to load!) is from the 30-minute long video Kydoimos. Original score by Chris Kallmyer.

Though contemporary - and uncomfortably prescient given the recent social media spat between the United States and North Korea regarding nuclear supremacy - Maisel’s work bears direct links to nineteenth-century landscape projects produced by photographers including Timothy O’Sullivan and William Henry Jackson as westward expansion progressed. Maisel references that history by pairing West Vertical Grid_02 (2014) a single albumen print beside South Ballistics Grid_04, Dugway Proving Ground, Utah (2014), a massive, nine-part grid of images he captured from above, shot on film and printed digitally. This arresting juxtaposition holds up both antique and contemporary photographic technologies as possible means of deciphering the once-pristine scorched landscape, but comprehension is incomplete. The effort to understand the consequences of expansion, development and military-industrial infiltration is thwarted.

Airforce Target Grid Building installation photograph. Courtesy of Haines Gallery and David Maisel. Photo by Robert Divers Herrick.

The absence that pervades Proving Ground is intensified in the image "Referee Module Interior" (header image for this article). The people who work at DPG, those whose efforts form the bulwark between the best and worst outcomes one can envision in such a setting are nowhere to be seen, but are represented by the elegantly limp safety gloves. The unused safety wear, paired with marked-up colored masking tape affixed to metal components, remind us that it is human agency and not mechanistic or procedural redundancy that keeps wholescale disaster at bay… for now.

KYDOIMOS video still #2. © David Maisel. Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery

Proving Ground is the latest chapter in Black Maps, Maisel’s long-form visual meditation on radically-modified environments worldwide. Rather than offering commentary or passing judgment on what he photographs, the artist leaves interpretation and the choice to act to those who see and absorb the information he provides. While all of the sites he has photographed rightly merit conversations about land use, resource conservation, and stewardship, Proving Ground activates something closer to fear. The natural, all-too-human drive to assuage fear is to seek knowledge. But when that knowledge is denied, even if it’s for the good of the nation and we who inhabit it, that fear settles into a deeper place. The answer to our questions, as “not now” was to Maisel’s initial query, may ultimately be “not now… but when?”