Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

Photographing disaster is complicated. In her pivotal work, On Photography, Susan Sontag described it as ridden with shock value, numbing and almost touristic. Later in her career, in her final book Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag revisited these ideas, arguing that war photography, despite its problems, provided a necessary documentation for the world to see. Contemporary photography of natural disasters can be colored by similar problems, often with skepticism around the photographer’s gaze and intents. New York City based photographer Ruben Natal-San Miguel confronted these issues when he flew to Puerto Rico in early December to make pictures of the destruction of his hometown paradise at the hands of Hurricane Maria. He transcends the clichés of disaster photography with his direct connection to those impacted, and his unconventional approach to visualizing it all.

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

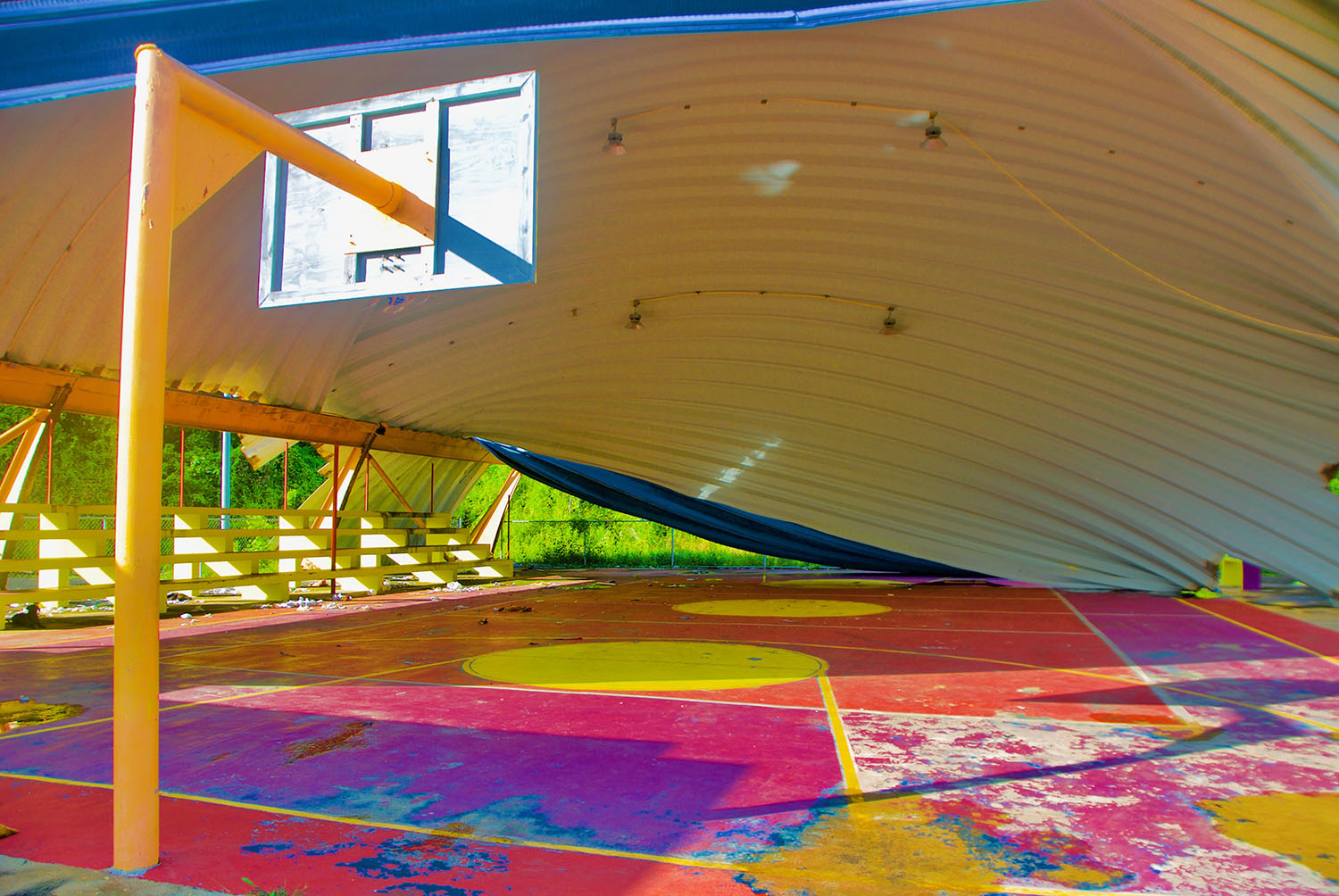

Natal-San Miguel, known for his bold documentary photographs of transitional communities across New York City, approached Puerto Rico with a similar eye. For the first leg of this project, he photographed in the interior rural parts of the territory, ground zero of the hurricane’s destruction path as well as the the poorest metropolitan areas of San Juan. In his words, his goal was to “document the revival of the island where I was born and where my family still lives, chronicle examples of community resolve to rise from the ruins, and record a people’s determination to restore strength and pride in culture.” His mother and sister’s homes were suffered severe home damage and flooding, and are still pending FEMA claims, and other relatives lost their homes.

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

While Natal-San Miguel communicates the pain and destruction, his photographs eclipse the disaster-photography trope with a strange, colorful electricity under nearly-pastel sunny skies. In one image, for example (the header image in this piece), the structure of a bathroom rises in the center of the frame, the only standing remnant of a wind-demolished house. Its aquatic teal tiles mirror a backdrop of ocean waves that descend infinitely. It looks almost staged, but is an unfortunate reality. In another ocean-viewed photograph, a refrigerator, houseplant and television sitting atop a tree-stump pedestal are the only remains. Everything else has been wiped out, and these household items exist somewhere between omen and talisman before more bright blue waves and sky.

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

“I think one of the things that learned from this experience,” says Natal-San Miguel, “is that the natural and manmade landscape are the best elements to start the narrative of a disaster of this level. The gorgeous days against totally decimated structures, homes and businesses are more relevant to convey a message, create visual impact and generate awareness.” At this stage, while Natal’s work includes a few portraits, it centers on the landscape to emphasize the desolation, emptiness and destruction more effectively than the human element. When he returns in the coming months, likely with the help of the Magnum Foundation Prince Claus Fund grant, he plans to focus on “the renewal stage” and include more images of people.

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

Throughout the process, Natal used (and will likely continue to use) Facebook as a public, yet personal for his experiences. On Christmas Eve he posted: “I saw and documented a lot of devastation today. “The photos are brutal, so brutal that, will not post any of them on Christmas Eve. But, this photo is one of resilience, perseverance, hope and I think is beautiful. Its beauty reminds me of when Mary and Joseph had baby Jesus in a very humble shack but, they were happy, there was a lot of joy around them, not because the abundance of possessions but, the spirit of joy, birth and Christmas.” He parallels this religious symbolism to the resilience of those impacted, and his mission to support their rebuild.

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

With any project of this nature, there’s a fine line between making opportunistic, visually exploitive imagery, and photographs that empathetic. Natal-San Miguel’s work falls into the latter, likely in part because he's photographing his home turf. “I resolve,” he says, “to chronicle those instances when people appear at a loss to inspire the sense of hope needed to spur renewal and to preserve their culture.”

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel

Photo © Ruben Natal-San Miguel