© Elinor Carucci

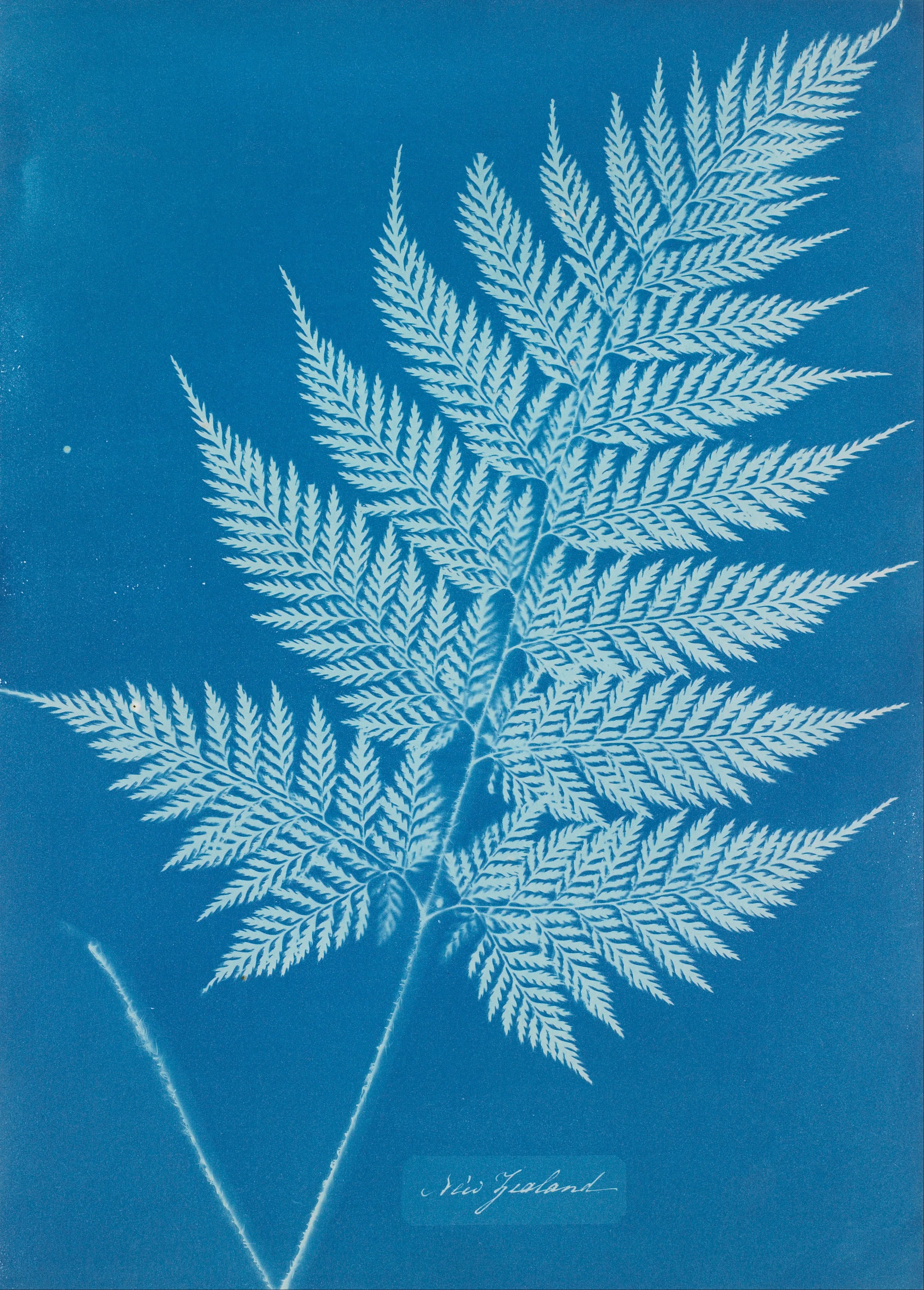

Color photography can trace its earliest roots to Anna Atkins' mid-nineteenth century botanical cyanotypes. While camera-less, her adoption of the process has led many to consider her to be the world's first female photographer.

Curator, historian and artist Ellen Carey's latest exhibition "Women in Colour," on display through September at New York City's Rubber Factory gallery, uses Atkins' legacy to trace the lineage of women working with color photography through present day. Hinging on the recent discovery of tetrachromacy, the hypothesis that women are genetically prone to better discern color than men, Carey uses this exhibition to ask how that might impact female photographers' decision to work in color and hopes to gain recognition for their often under-exposed work. I spoke with Ellen Carey to learn more about the ideas behind her research and exhibition.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

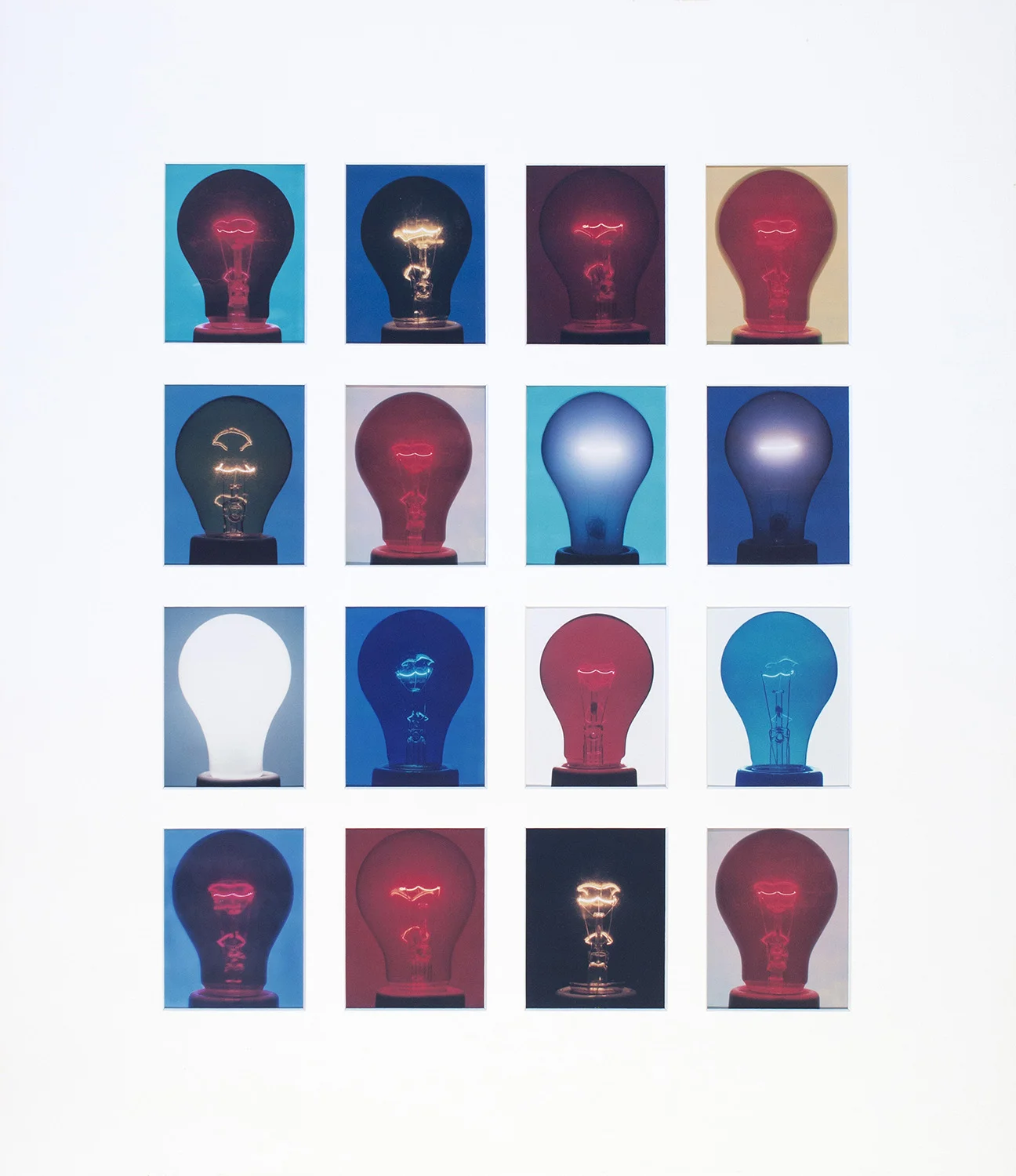

© Amanda Means

Jon Feinstein: I'll start with a question I was asked on a panel re: the biennial exhibition "31 Women in Art Photography" that I co-curated from 2008-2012: "Why are gender-specific exhibitions important today?"

Ellen Carey: Since women practitioners in the visual arts have been excluded from the hierarchy of public exhibitions for centuries, I think it is always important to add to that discourse in herstory. Photography is uniquely positioned in many ways. Originally an “empty” field, not considered “serious art” as it was considered invention, science, technology, process, camera, machine, chemistry and film, women “camera operators” were witnesses to its discovery and development at the dawn of the medium, through the twentieth century into all of its advances today. Photography’s history is short, compared to the other visual areas of expression — painting, sculpture — in politics the women’s suffragette movement begins in England in 1906.

Photography is not gender-coded the way other disciplines have been. This fact allows women creative freedom, forging their visions in new territories, pioneers on their own terms, without the cultural and historical freight of bias, male or otherwise, in art.

Feinstein: How did this exhibition and your initial research come about?

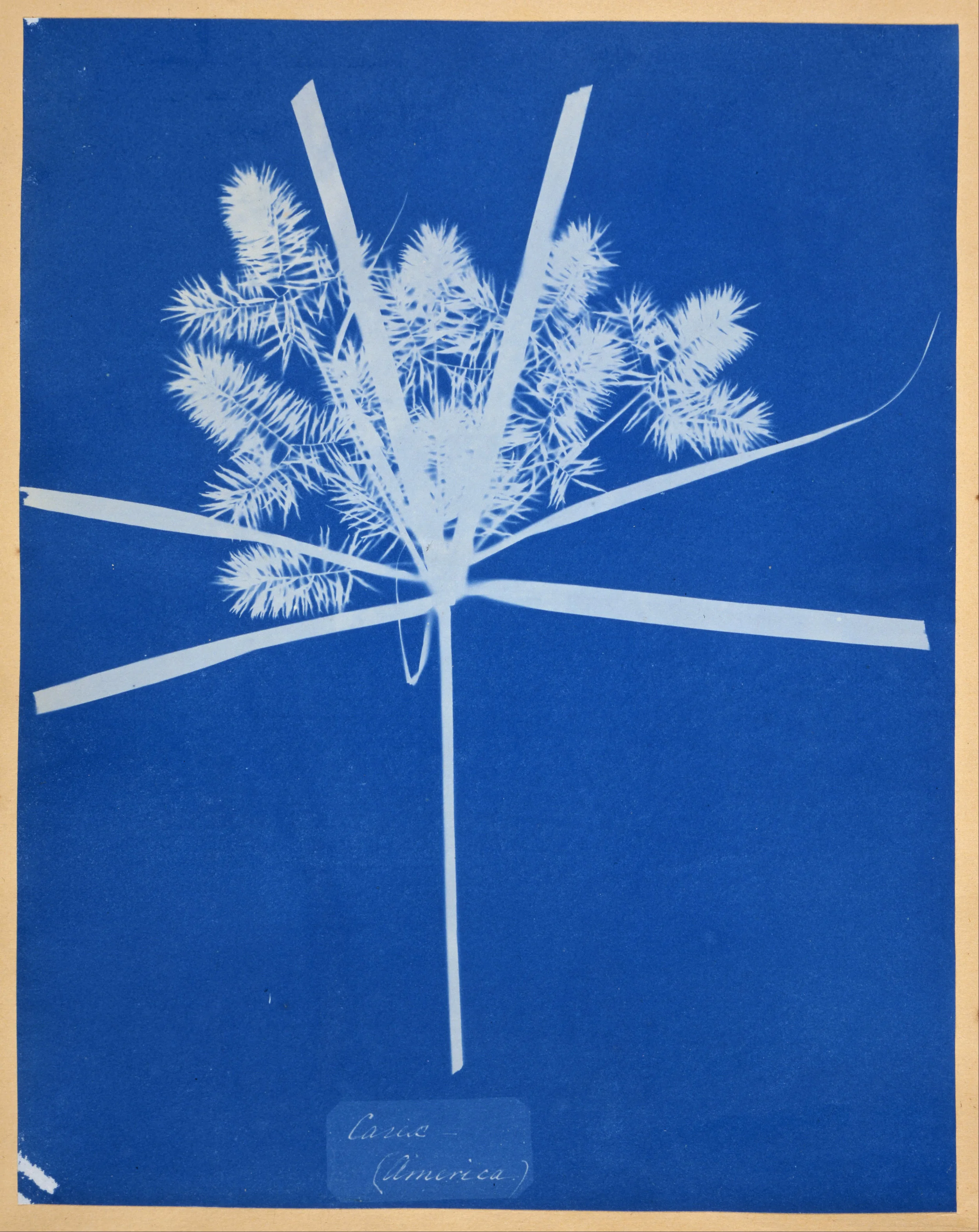

Carey: My research on the history of color photography noted an absence that prompted a question: “Where would color photography and women practitioners be without Anna Atkins?" The British Victorian, Anna Atkins (1799-1871), was the first woman photographer, the first working in color, found in her blue cyanotypes, which she partnered with Henry Fox Talbot’s photogram. Gender codes of Atkins’ blue/feminine versus Talbot’s brown/masculine (italics mine) underscore divisions in content, context and concept, adding to the discourse around male and female sight, found in the biology of seeing. Color is light, seen in a rainbow; light is photography’s indexical. Photograms and cyanotypes are transformed in her “sun pictures” as drawing with light, a nineteenth century phrase that describes the word "photography" - its Greek roots mean light drawing from phōs and graphé.

Ellen, my Catholic girl’s birth name, traces its roots to Irish/Gaelic/Celtic; it means "light" or "bringer of light." Anna Atkins is a "Woman in Colour," struck by light — inspiration — that begins the discourse around color and photography as object and form, technical and visual advancement. What is absent? My hypothesis supports the recognition of women practitioners, whose historical and collective contributions in color photography remain “under-exposed” to borrow a photographic term.

© Anna Atkins circa 1849-1858

Feinstein: When did you begin to focus your research on women working in color specifically?

Carey: In 2000, I began a concentrated focus on color, learning its cultural history from leading authorities such as Michel Pastoureau, as well as its meaning in the visual arts from other scholars over the centuries. I began a deeper commitment to my discipline, a lot of printing in the color darkroom (2000-2017), a ‘light-tight’ environment; all experimental, all light, all color; the final results documented the perfomative aspect in both practices as well as my ideas. Then I noticed something in my research. It was puzzling at first, a bit like detective work, my independent scholarship and writing, it falls under Pictus & Writ (2008-2017). It was the same curiosity and intuition that led me to Man Ray's photographic discovery, his “hidden” signature in his 1935 self-portrait "Space Writing."

I noticed a lot of women using color in photography. This led to my project, which led to the current exhibition at Rubber Factory. Mike Tan, the gallery owner, wanted to work with me and asked what would I like to do. This was my first choice, we discussed it, he said “yes,” and I began contacting the photographers, all whom agreed and found my research fascinating.

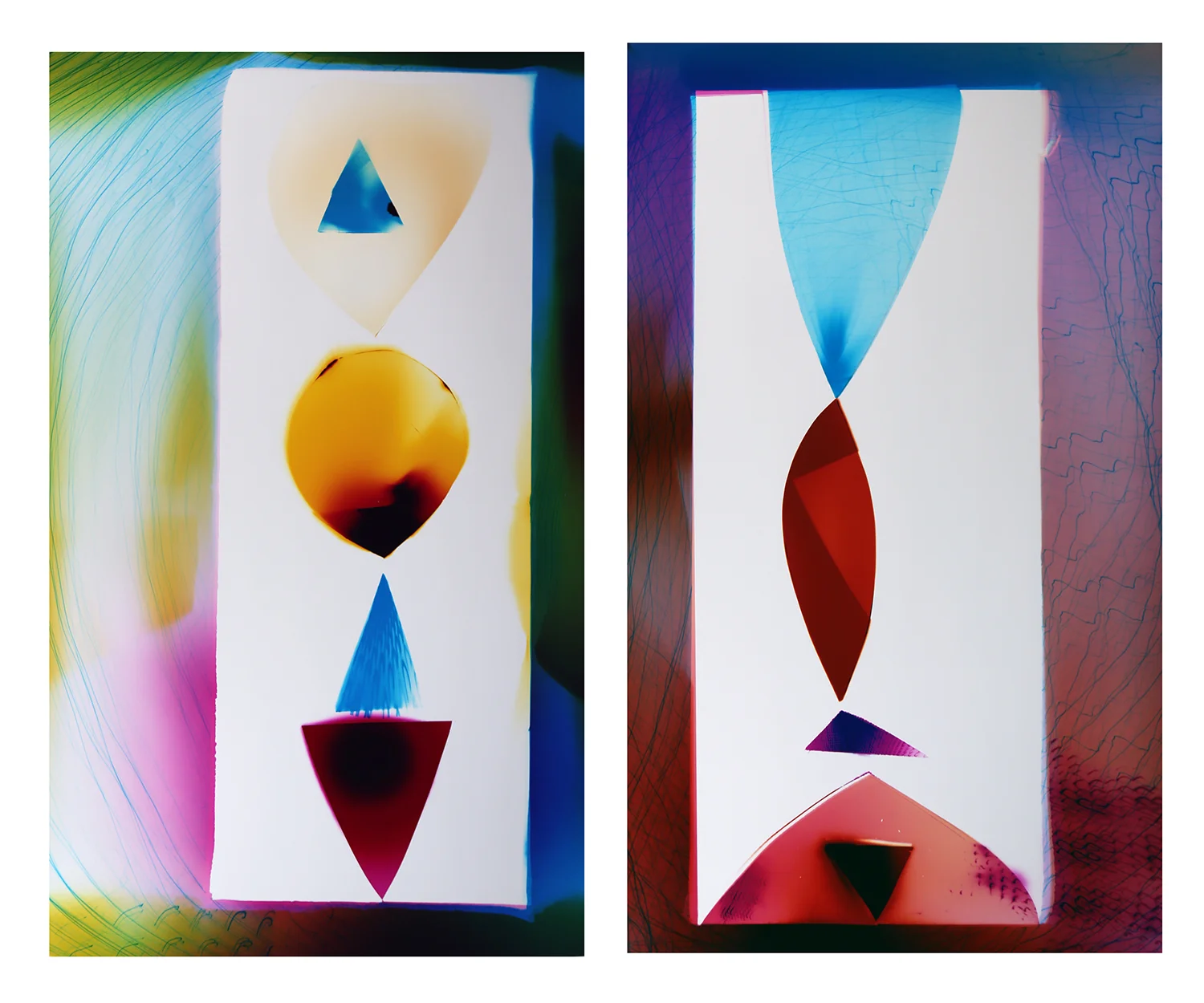

© Liz Nielson

Feinstein: You use the British spelling "Colour" in the exhibition title, tied to Anna Atkins being a British artist. Can you elaborate on the intention behind this?

Carey: "Women in Colour" advances fresh, new scholarship, a distinct category, tracing its origins to gender-specificity and female colour in photography, time: in nineteenth century, and place: England. In doing so, it challenges and reframes the big question posed by Linda Nochlin in 1971: “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Today, the answer to Nochlin’s question has improved, but still exists. My femme brut(e), a phrase I developed, brings it up for (re)examination; my research finds color blindness co-exists with gender blindness. Photography has many great women practitioners, many use color: “Why?”

Color is technically challenging, requires different skill sets than black and white, and is expensive. Does this highlight female power, financial autonomy; breaking taboos of “woman artist” in art, science and chemistry? Why do women choose color? More “attractive,” or since photography began as an “empty” field, women were free from the tyranny of art history allowing herstory, and in this context, does color paradoxically offer more freedom? The late Victorian, Lady Sarah Angelina Acland follows Atkins, locating colour photography as female and British; colour, the British-English spelling, highlights its UK origins. "Women in Colour: Anna Atkins, Color Photography, and Those Struck by Light" provides a scholarly context, emphasizing my hypothesis; this exhibit re-frames this political phrase, shifting the “of” and replacing it with “in” photography; it highlights women’s contribution to colour/color photography, an area of unacknowledged scholarship is now added to our discourse.

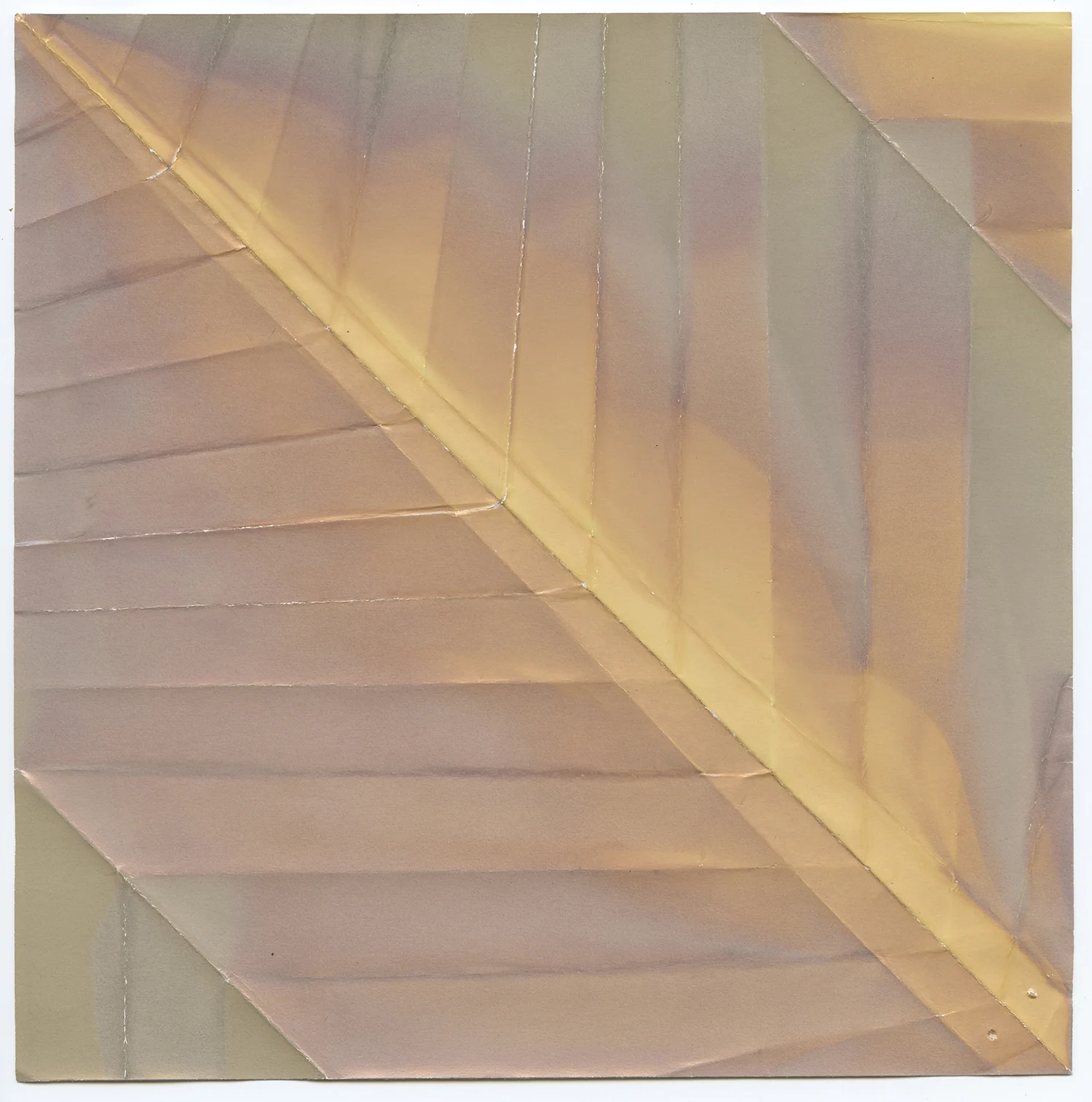

© Moira McDonald

Feinstein: Thinking about the use of the word “color/colour,” does race and/or cultural identity play into the exhibition thesis and your curatorial process?

Carey: The phrase "women of color" was coined in 1977 from within the minority report to the National Women's Conference organized by Eleanor Smeal, then president of NOW and Congresswoman Bella Abzug (NY) at the behest of President Carter in Houston where black women presented their Black Women's Agenda. Minority women other than African-American women wanted to be included in the Black Women's Agenda plank and the women of color phrase originated to include them.

Loretta Ross explains this in this YouTube video. In 1980, Audre Lorde and Barbara Smith founded Kitchen Table Press: Women of Color Press. Poet Audre Lorde who had a hand in founding The Combahee River Collective in 1974, was influenced by these collective women of color. It was from there that she and another woman founded Kitchen Table Press: Women of Color Press.

What a rich and complex politico-cultural herstory belongs to this simple phrase that marks a time when minority women consciously experienced themselves collectively for the first time as women of color. My phrase "women in color" echoes this in my project "Women in Colour: Anna Atkins, Color Photography and Those Struck by Light."

© Mariah Robertson

Feinstein: Does transgender identity fit into your thoughts on the legacy of "Women in Colour?"

Carey: As stated above, this is a new field, I welcome all inquiries, and there are enough art historians, gender-studies scholars, photography curators and visual practitioners to expand on my research. It could easily translate to other areas in the visual arts such as "Women in Color: Fire and Ice," for ceramics/clay and glass/sculpture, so I do have ideas. I think a panel would be great, a book of course, and a museum exhibition would be wonderful. In this context, I am currently in dialogue with a museum that could do all three, and I would like to include scientists, scholars, and other experts who specialize in color.

© Anna Atkins circa mid 19th century

Feinstein: How would you answer the question you pose in the exhibition statement: "Where would color photography and women practitioners be without the work of Anna Atkins?"

Carey: My research on the origins and history of color photography noticed an absence that prompted this question. A pioneer in color photography, Atkins has, in my research, many “firsts.” Her legacy casts a long “shadow”, a characteristic specific to photography. In my hypothesis, color photography has a separate and unacknowledged history located in gender, a beginning found in the fateful, twin aspects of the female Anna Atkins and her blue cyanotypes. Blue is often the color gender-coded for boys, yet her botanical studies say water, feminine, soft. Her degree of sophistication and keen, visual intelligence prefigures a focus on the shift towards color as the primary “container” of artistic expression.

“Would her cyanotypes have the same meaning if done in Talbot’s non-colors?” My answer: “No!” Anna Atkins is very significant as is her work in cyanotype. For me, it is extremely important to know your history, and in this case, it is female and color, process in photography. The whole experience is richer for me, as practitioner and scholar, as curator and picture maker. I understand the efforts behind making a picture and am indebted to her and her work, which she gave as gifts to others and her work keeps giving, even today. Anna Atkins is central to this exhibition because she was not only the first photographer, but also the first photographer working in color.

© Anna Atkins circa mid 19th century

Feinstein: Why else is she important to you?

Carey: First, all of Atkins' work is significant to the scholarship of my project titled "Women in Color: Anna Atkins, Color Photography" and "Those Struck by Light." It is here that the object is free to “speak” under art’s rainbow, in the language of color, finding expression by the colorful (or full of color) hand/imagination of Atkins; the history of color photography begins with her; the first woman practitioner, albeit camera-less and the first in color vis-à-vis the cyanotype; the first to explore abstract and minimalism in composition, adding her own handwriting/text ‘word art’ again another first; her book, another first, pre-dates Talbot’s.

However, of particular interest to me is the transformative power of her keen, visual intelligence, in color and photography, as tools for artistic expression to render an image in crisp detail or soft, out-of-focus, whereby she layers her botanical studies in clusters or alone, within her sophisticated compositions that render high visual impact surrounded by her delicate, filigreed handwriting, simultaneously autobiographic and word, visual and descriptive, process and object; all using light.

Her blue image transforms the physical object, the contrast can be seen her drawings of similar objects in her studies, using the photogram-as-cyanotype, an experience and experiment that takes place in: colour and color; size and scale; off-frame space and line-as-open form; symmetry and asymmetry; chaos and order; in: minimal and abstract compositions, in: variations of shade and hue, a single colour/color palette of blue, her final images are no bigger than a page in a book. To date, my research has these multiple links as an area that is under-researched and without context, now new.

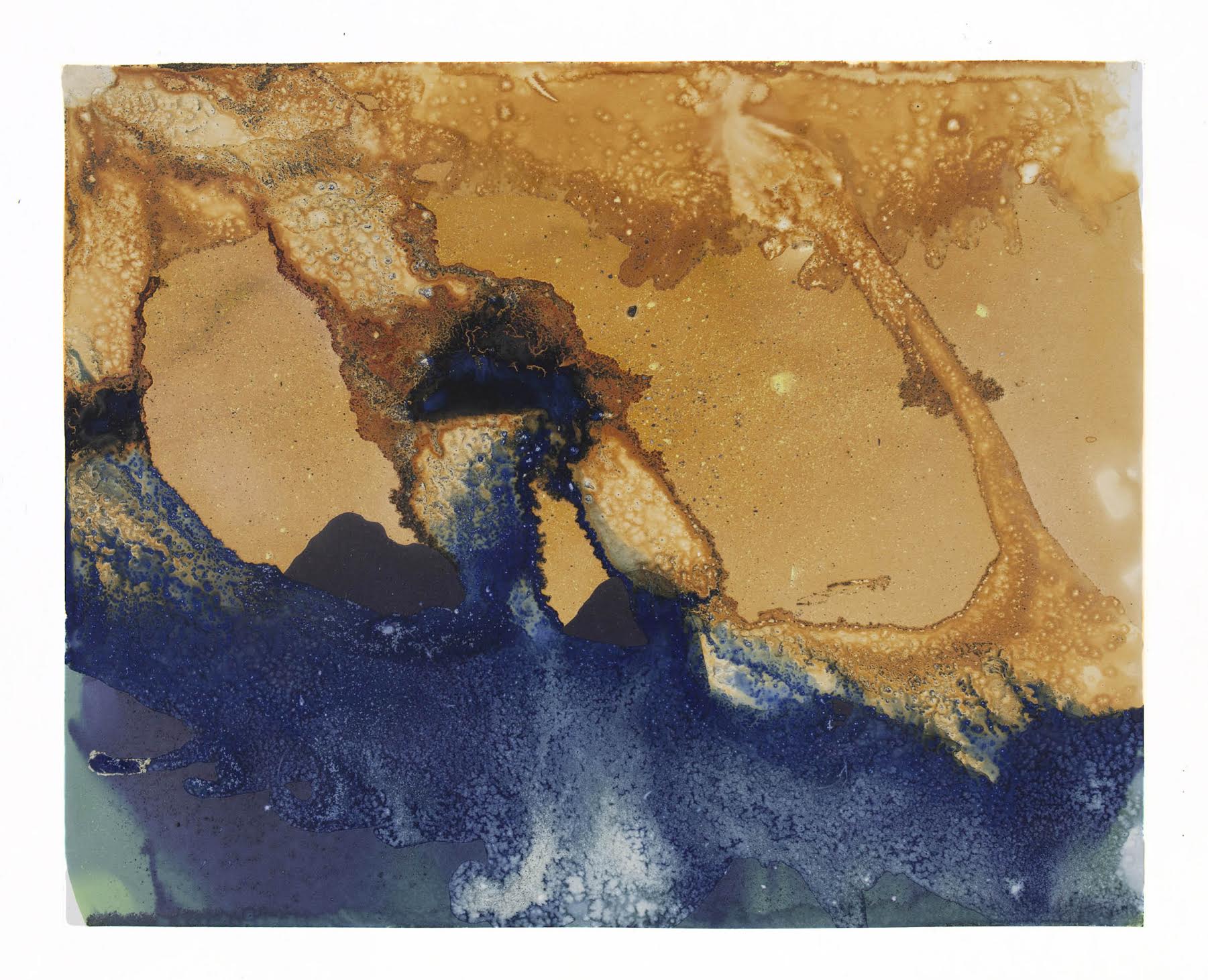

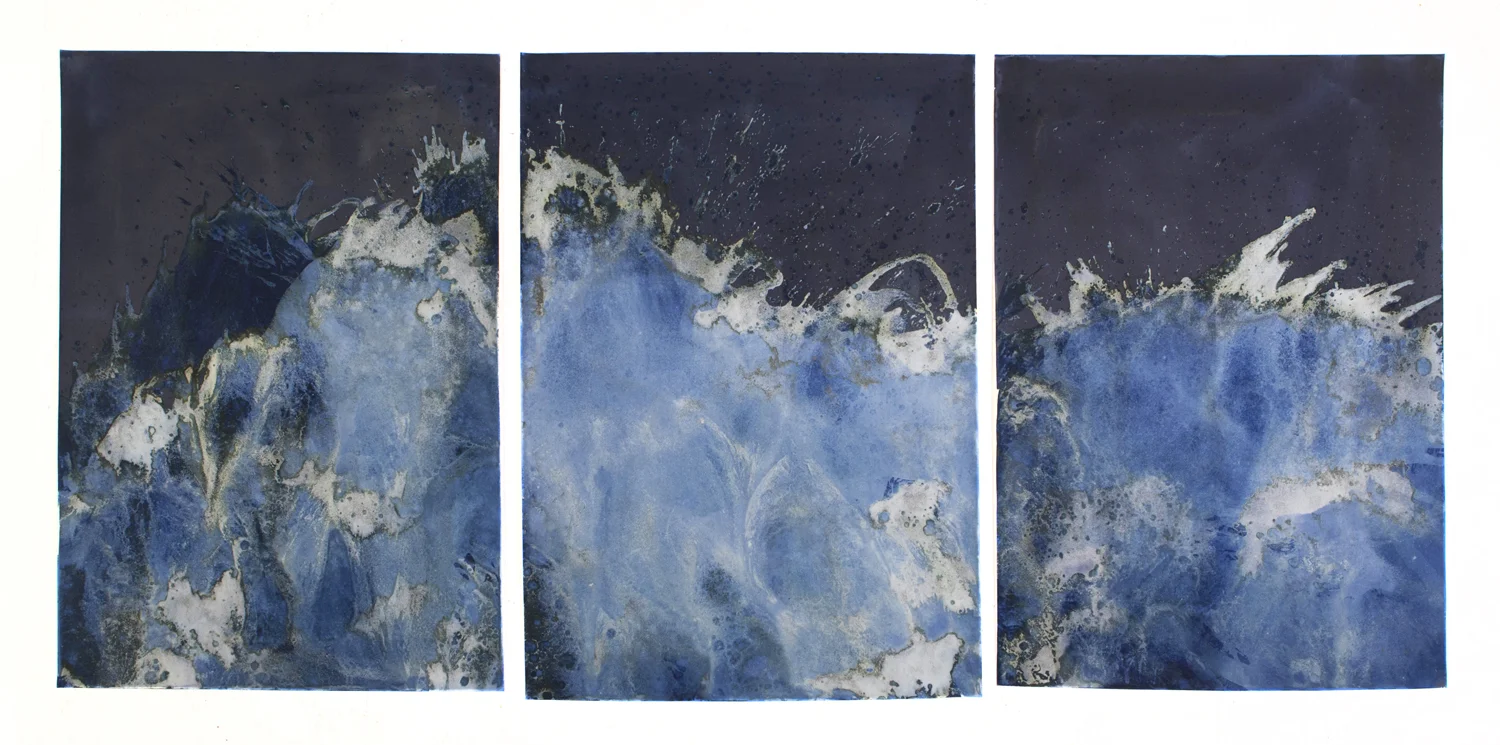

© Meghann Riepenhoff

© Meghann Riepenhoff

Feinstein: I think your inclusion of Meghann Riepenhoff's work is particularly interesting with regard to use of the cyanotype. Why do you think she was important to include in this exhibition?

Carey: She and her work are direct links to Anna Atkins in the nineteenth century to our present twenty-first century. Her work is fresh and invigorating, introducing size and scale in unimaginable ways and formats yet shares affinities with Atkins’ work through her use of sun, water, process, and chemistry. As Robert Smithson states: “Size can be a crack in the wall or the Grand Canyon.” She places the photographer in an active role, taking time to make these labor-intensive cyanotypes, exquisite in their technical acumen and artistic intent.

She merges the ‘real’ in nature and light with randomness and chance, allowing the process to participate in the making her large-scale abstract, unique work. Bold and complicated, seemly simple yet altogether striking, these images contain high visual impact where the subject matter is transformed, literally and figuratively, through process and photography, the blue of water and blue of sky, majestic and monumental cyanotypes. I admire her work greatly, having failed miserably at making cyanotypes myself, I can appreciate the effort and conviction, patience and knowledge, and all that goes into it.

© Patty Carroll

© Cindy Sherman

Feinstein: There's a mix of portraiture and abstraction - photographers using a range of methods, all applying a seemingly radical approach to how they use color. Can you talk a bit about your curatorial process?

Carey: I wanted to represent a range of ideas in "picture signs" but have them be a departure from the traditional notions of the images as in a portrait, a landscape, and a still life, so forth in tandem with the colors equal to this departure. Sherman was the first person I asked to participate and I wanted one of her clown images. She loved the curatorial idea and was intrigued with my research, in the context which it was presented. Then I went down my list, everyone agreed to participate, although some photographers like Sandy Skoglund, did not have the exact photograph I love -- "Radioactive Cats."

Feinstein: I'm particularly drawn to Laurie Simmons' How We See portrait -- it's much different than the work I normally associate with her, and comments on many of the ideas you discuss in your thesis -- vision, color theory, etc. What moves you most about this image?

Carey: The illusion is very clever, it comments on sight and non-sight simultaneously, while the photograph also presents race and gender. A metaphor for four cones instead of three, illusion versus reality is a large theme in photography.

© Laurie Simmons

© Carrie Mae Weems

Feinstein: I'm also drawn to Carrie Mae Weems' image Color Real and Imagined. Like Simmons', it feels a bit different aesthetically from the images I commonly associate with her practice. There's a tension between the layers.

Carey: She is using color to highlight color, commenting on race and gender. It is a powerful image and has a high visual impact, underscoring my concepts around female sight and gender bias, a perception in our medium that had a long herstory.

Feinstein: Much of the curatorial bend on this exhibition centers on the lack of recognition for female artists. I see a connection to the Guerilla Girls' research on gender imbalance in the mainstream art world of the 80s, and more recently, the Brainstormers' work as well. Do you see the same sense of urgency today?

Carey: Where is the 1-800-Art-World hotline when you need it? Of course, the problem still exists! It has improved but it is still very much alive and doing quite well! It is called institutional sexism and global misogyny. I see it every day, at work, in the art world; it is everywhere, first announcing itself to me when I arrived at Kansas City Art Institute as a student in 1971. There were no female professors, most of the female students were in painting, and certainly Janson’s History of Art, a book the size of an old-fashioned telephone book or huge dictionary included no women artists. So welcome to the planet, girls.

Why it still exists is beyond me, the history of its damage to our female population is extensive and well documented in all fields. Gender imbalance is too soft, too academic. I prefer the reality of the situation, which is brutal and unpredictable, with many factors along the way in a woman’s life, and for a woman artist, my phrase femme brut(e) is more accurate.

I plan on starting a foundation with that phrase and starting it soon to support women artists and photographers who break with boundaries and advance visual thinking. I am forever grateful to my parents for raising me outside of society’s gender-codes, allowing me to fulfill my dreams and ambitions, destiny and fate, believing as they did in education, hard work and being the person I wanted to be and have become. My Catholic birth name Ellen means “light” or “bringer of light” in Gaelic/Celtic/Irish, a prescient gift. I am also grateful to all that have mentored me along the way, on my life’s journey, the list is long of teachers, fellow photographers, art historians, artists, museums, galleries, alternative spaces, collectors, curators, scholars, granting agencies and so forth.

© Marion Belanger

© Susan Derges

Feinstein: You've discussed an interest in the parallels between gender blindness and color blindness (Tetrachromacy). Why is this crucial to "Women in Colour?"

Carey: New scientific data shows that a DNA gene called tetrachromacy allows some women an ability to see more color if they test positive for the gene and only women carry it. Having four cones instead of three multiplies the color one can discern; color blindness is twenty times more frequent in men. Is this groundbreaking news the first from the dawn of photography, undiscovered from then until now, beginning with Atkins and linking photographers through the generations? My research suggests that this is the case; men and women, different genders, see colors differently.

© Ellen Carey

Feinstein: How does your own work fit into all of this?

Carey: The 20th century art movements — Abstract Expressionism, Minimal, Conceptual Art — give my experimental photogram work a context in the 21st century, from this camera-less method at the dawn of the medium in the 19th century to fresh interpretations in the present. My color series "Dings & Shadows" (2010-2017) re-configures the term "blow up" to highlight visual impact in both form and hue in my abstract compositions. The ding, once a lonely and loathsome error, sat forever in the taboo margins of photographic printing, now it gains a new purpose.

When looking at my work, people often ask: “How is this picture made?” And the question is often followed by: “What is this a picture of?” The first question addresses photography as process. The photographic object often involves an intersection of process and invention, as does the practice of photography itself, and in traditional photography both the process and the invention are “transparent,” in that they are understood to be a means to an end, namely, to produce a picture as a representational object. The process is subordinated to the product. The second question addresses the apparent conundrum of photographic abstraction: the photographic image without a representational “picture” to read. Our culturally and historically prescribed expectations for this medium are that a photograph should narrate and document, and that it should reveal no trace of the “work” of its production.

Feinstein: What do you hope viewers will glean from this exhibition?

Carey: A greater understanding of color in photography and the historical role and collective contributions of the women practitioners in it. I aim to free the picture from the tyranny of photography’s historical imperative to record and reveal “things.” My work intentionally upends traditional methods of “rendering” a photographic image with unusual approaches and combinations. This forces a break from the past, freeing a picture from a hierarchy of things to be captured to a picture that is made. I hope this exhibition as "Women in Colour: Anna Atkins, Color Photography and Those Struck by Light" begins to address this oversight, bringing fresh, new research to an amazing group of women photographers, who, through color and their images, have greatly advanced our historical and now global picture culture.

---

Women in Colour is on display at NYC's Rubber Factory gallery August 19th through September 27th, 2017, with an opening reception on August 19th at 6pm.