© Anthony Gerace

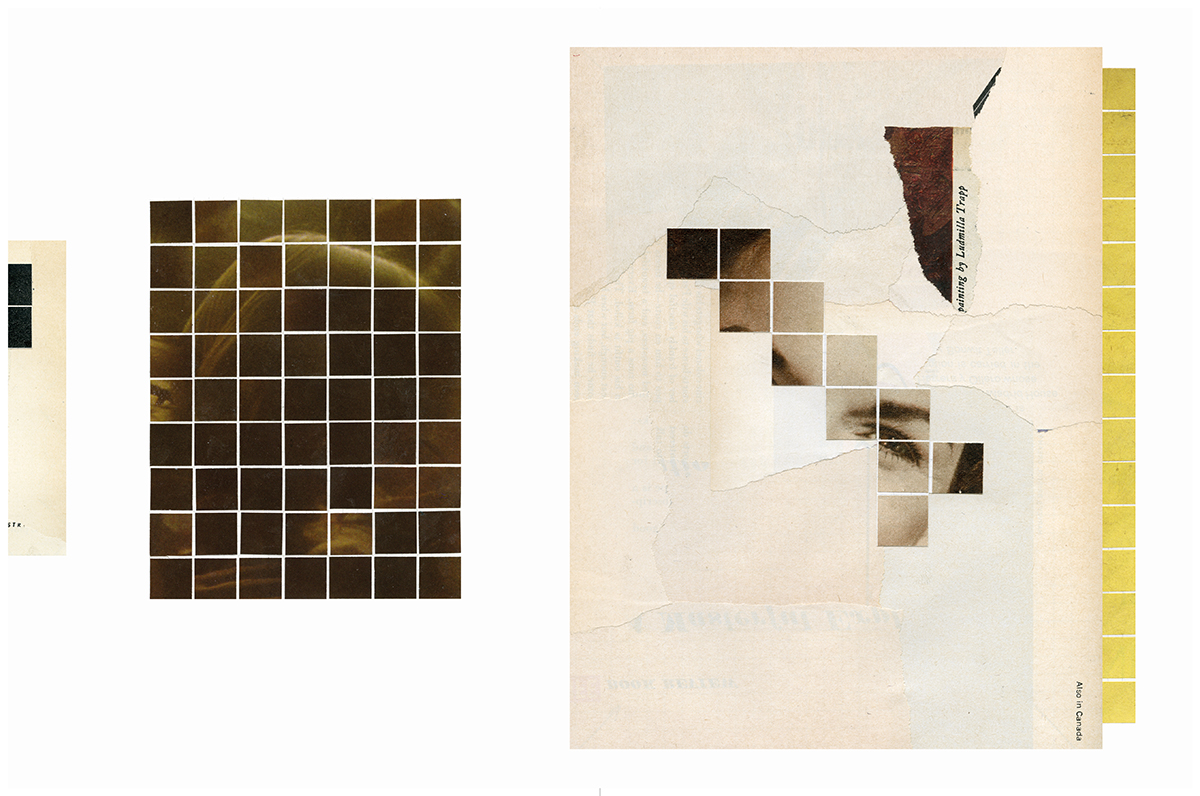

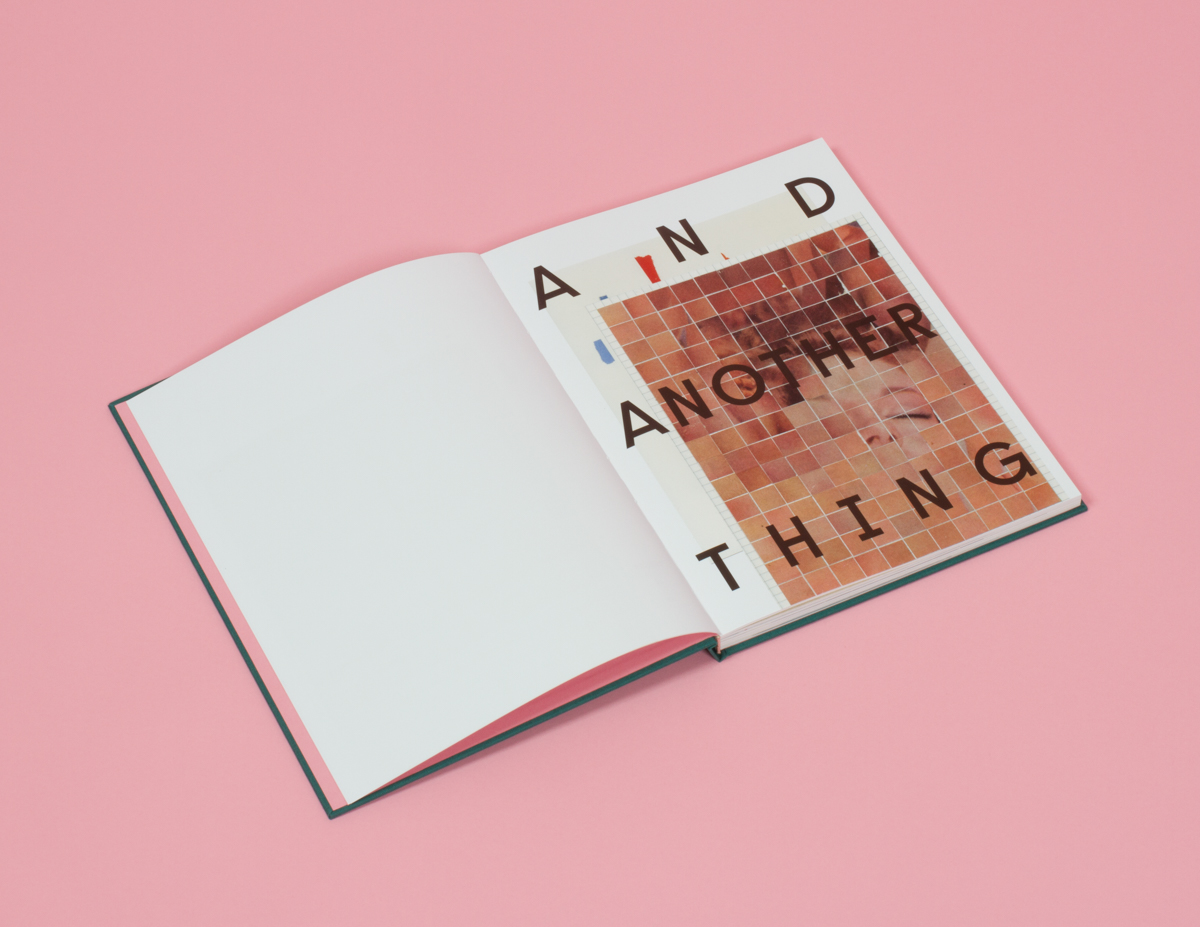

For nearly a decade, London-based artist Anthony Gerace has been making inspired collages with ultimate precision. Pulling material from the 1920s through the 1950s, Gerace cuts, pulls apart, and reassembles past remnants into sometimes humorous, sometimes disconcerting compositions, often using a grid as a psychological and organizational tool. He recently worked with Aint-Bad to publish And Another Thing, a collection of this work from the past seven years, which he describes as being less of an anthology, and more of "meditation on the nature and physicality of the medium as well as an individual piece of work in its own right." I contacted Gerace to learn more.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

© Anthony Gerace

Jon Feinstein: Your title "And Another Thing" is both cryptic and playful. Tell me a bit about the ideas behind it...

Anthony Gerace: And Another Thing was originally going to be the title of my first solo show in Italy, and I started hovering around those three words in the lead up to that show because they seemed perfect: it’s simultaneously a declaration, a rejoinder and a lament. Because what’s the point of having "another thing"? Why do we feel the need for things? But then of course my work is entirely about things, about the object-ness of history and about the power of objects to break free from their historical context and comment on the present and the past simultaneously. As much as my work is representational it’s also about the physicality of paper, and the way that history becomes evident not from what the image represents but for what the surface of the image says about where it’s been and what it is. So, in that sense the book is just another thing, another thing to be consigned to a very quickly moving history but also another thing to add to the body of work that I’ve been cultivating for the last ten years. It’s a physical object full of images ruminating on the aesthetic, temporal, and cultural consequences of physical objects.

Feinstein: Where are you getting your source material?

Gerace: All over the place—typically magazines from the 30s-60s, but also my own photos and portraits, and then onward to the ephemera and garbage that I encounter and collect. The book has been important for me because it’s shown where the work can go, now that this stage of the work is, effectively, done. It’s shown me that a receipt for a Jeff Nichols movie that hung around in my pocket for weeks is as artistically viable as pieces that I’ve laboured over, physically and conceptually, for years.

© Anthony Gerace

Feinstein: Who is inspiring you now, art, photo or otherwise?

Gerace: So many people. It’s an ever-growing list. When I was in New York promoting the book I was lucky enough to stumble across Sam Contis’ Deep Springs show at Klaus Von Nichtssagend gallery—it was one of the most moving photography shows I’ve seen, all the more so because I totally missed the artists’ statement and saw these otherworldly, beautiful views of the high desert and these men without context, which made me endlessly curious about her work. I was then even luckier to see her in conversation in London when I returned, and it gave me two very different impressions of that work. I think Deep Springs is a template for everything photography can and should be: humane, engaging, beautiful and strange, all at once. And then people like Thomas Albdorf and Chrystel Lebas, who are both really pushing what photography can be through experiments in form. And my studio mate John Gribben, because I love his work and enjoy getting a glimpse into his process. And then all of the other people and artists who deeply influence me, too many of whom to name…

Feinstein: Much of this work seems to be about obstructing or destroying the human form. Would you agree?

Gerace: Yes, definitely, although I think it’s less about “destroying the human form” as it is about making clear the effects of time on people and their image representations. That obstruction is just the clearest way to put that idea forward.

© Anthony Gerace

Feinstein: What's the significance of the grid within your collages?

Gerace: I’m not sure if it’s significant as a thing; it was a form I settled on after a lot of experimentation and have worked into the ground since, and I think that it’s modulations into different forms (Stakes, There Must Be More to Life Than This, etc) are a product of wanting to push what I found successful about that rigorous form to new places. It’s become sort of central to my work, and so in that respect is significant, I guess? All I know is that I introduce myself to people as “someone who cuts out tiny squares of paper”, and it’s not not true…

Feinstein: Your use of text feels pretty intentioned as well...

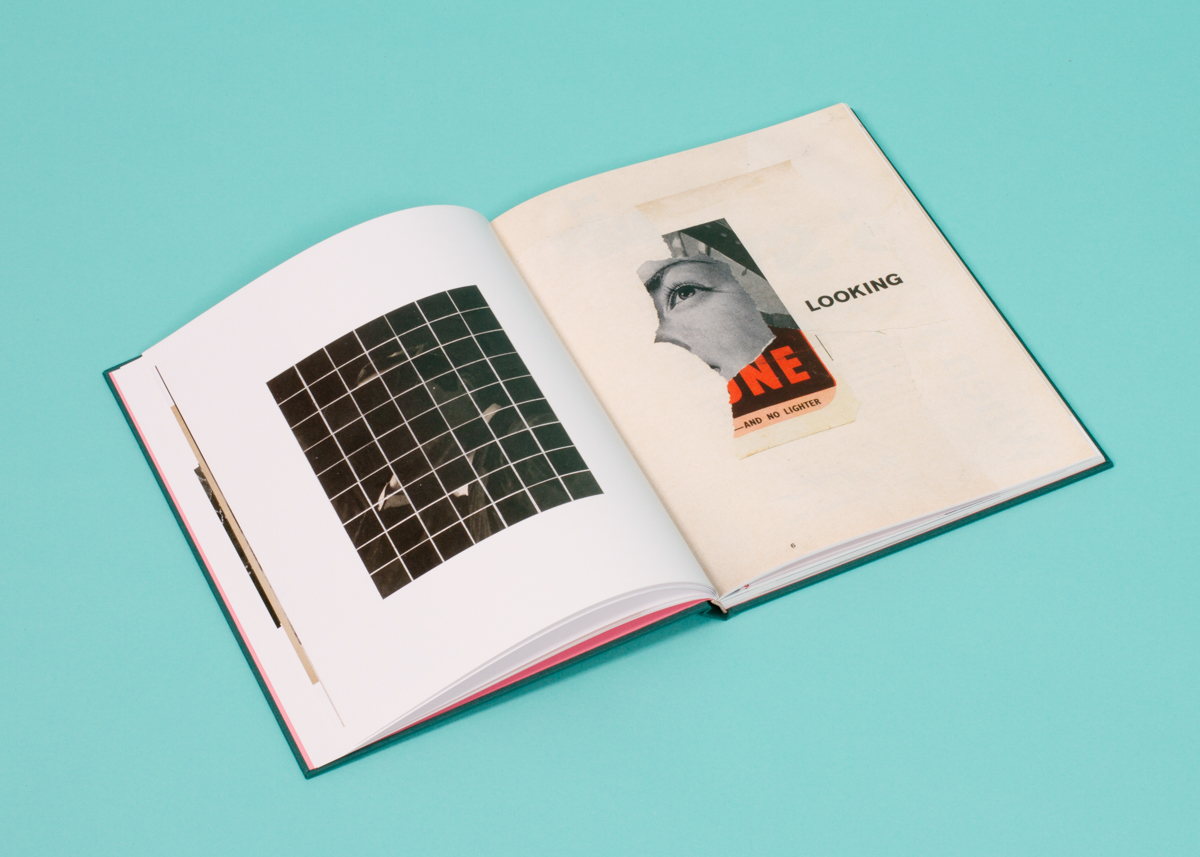

Gerace: Text has become a bigger and bigger element in my work since I began my People Living series six years ago: I really liked the way that randomness started intersecting this highly regulated, almost OCD way of working and I liked that for whatever reason, that text began to comment on the work itself and what the work was trying to do. That’s not always the case, of course, but I think a lot of the pieces in the book that incorporate text tend to act as guideposts for what the work is trying to say. “This says it all”, “Don’t ask for, insist on”, “the execution is the strategy”—all of these declarative bits of ad speak taken from their original context become commentary but also have this disembodied voice that’s relatively consistent in tone, yet comes from nowhere…

© Anthony Gerace

Feinstein: In her essay at the end of the book, Laura Todd references a destruction of the linear narrative -- the idea that the book is its own piece, or art object with no beginning, middle, or end. Can you elaborate on this?

Gerace: One thing I didn’t want with And Another Thing was for it to simply be a catalog of my work from the past six or seven years, or to be a staid thing with an image per page or two images per page or a very standardised layout. I wanted the work to be seen as a totality rather than a continuum, because I think it speaks to a lot of the themes in my work and in collage in general, and allowed me to bring out certain elements that might be missed in a typical display. I wanted to subvert the idea of temporality within the book, both from page to page and overall; even though there’s a direct course through it, each repetition of compositions makes you consider the one before it, so that, ideally, the viewer moves forward and backward through the book, constantly revisiting previous pieces to see how they relate to the ones that come after.

© Anthony Gerace

© Anthony Gerace

Feinstein: It's interesting for me to see you integrating some of your commercial work and album covers into this book, repurposing it and removing its commercial context.

Gerace: Yeah, I mean I’m lucky enough to be able to fold my art practice into commercial work, so it only made sense to take that work and reapply it to the setting from which it came. The piece I think you’re talking about is the cover for Julia Kent’s Asperities, which was a really interesting project to work on, both because Julia and Tony were very open with the art direction, but also because Julia’s music operates in a similar way to how I work. Then, a lot of other commercial work will come out of various series’ and ideas that I’m constantly thinking about, so to me it’d feel disingenuous not to include that sort of work, both because I think that recontextualisation comments on a lot of the themes that I’m exploring and also because it’s important to my practice overall.

© Anthony Gerace

Feinstein: You work with both collage and straight photography. Which came first for you in your artistic practice?

Gerace: It would depend where and how you defined my practice beginning. I bought a Nikon FM2 when I was in the 10th grade, and my parents were kind enough to buy me film and MoMA photo survey books, and then I moved on to collage through zine making, but whether this was an actual beginning to an art practice, I’m not sure. I stopped making art for a long time. I only picked it back up again when I began to promote bands and needed someone to make the posters, and then I went to photography and collage equally, only as a basis for those actions. I didn’t really see the potential for the work as it’s own thing until seven or eight years ago and at that point both practices were pretty entwined. I don’t know how anything starts. But I know they can’t exist without each other now.

Feinstein: So much of this work is about making sense of form and representation, which are largely external forces. Where do you personally fit into this work?

Gerace: For me, the work is primarily about what it means to make the work, to literally destroy bits of history (albeit a somewhat useless history) in order to create something new. So I hesitate to put myself into my work at all, because these pieces, and my art practice in general, is so often about the eradication of the person in the face of history (through time but also through objects), and history’s conditional anonymity, that to say the work is about me at all feels somewhat wrong. That said, there are instances: I included the dual self-portrait at the end to firmly place myself in the same context as the subjects I’m dealing with, and to sort of assert my own eventual abstraction as well. Likewise, I think the place I’m present in the work is in the typography; whereas so many of these pieces (and so many of my photographs) are about seizing visual opportunities and operating within a set of modalities, the typography that’s there is something that I’ve inserted, either to make a point about the work, to add humour, or to comment on the act of creating. I wouldn’t have known to say that even a year ago; it’s only been with time and the broader context of my own body of work that I’ve been able to see how important those elements are in charting a path through the work.

© Anthony Gerace

© Anthony Gerace

© Anthony Gerace

BIO: Anthony Gerace lives and works in London, working primarily in collage, portraiture and landscape. His work has been featured in Elephant, It’s Nice That, Dezeen, and AnOther, among others. His commissioned work has appeared in the New York Times, the Criterion Collection, the Atlantic, and PORT, among others. He is originally from Toronto, Ontario.