© Borjana Ventzislavova, I dreamed we were alive, 2012 / Bildrecht, Vienna 2017. Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

I Dreamed We Were Alive, curated by Sophie Haslinger and Verena Kaspar-Eisert, on view at Vienna's Kunst Haus Wien through June 18th collects five artists described as “[exploring] intimate moments and personal experiences through the medium of photography.” The curators give each of the four of the artists a gallery wall, while placing the fifth among the others in a “meta-level” exhibition. There is a wide variety of photography on display from artists Yulia Tikhomirova, Lena Rosa Händle, Hanna Putz, Ekaterina Anohkina, and Borjana Ventzislavova: black and white, color, digital, film, snapshot-style, candids, portraits, landscapes. Despite some truly eye-catching and satisfying motifs and rhythms created by clever juxtapositions, the displays, taken on the whole, are a bit uneven. Some of the artists’ contributions stand out more than others, creating an experience that is unfortunately not more than the sum of its parts.

Exhibition Review by Deborah Krieger

© Ekaterina Anokhina, aus 25 weeks of winter 1, 2013. Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

© Yulia Tikhomirova Baltica 2003 / 2016. Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

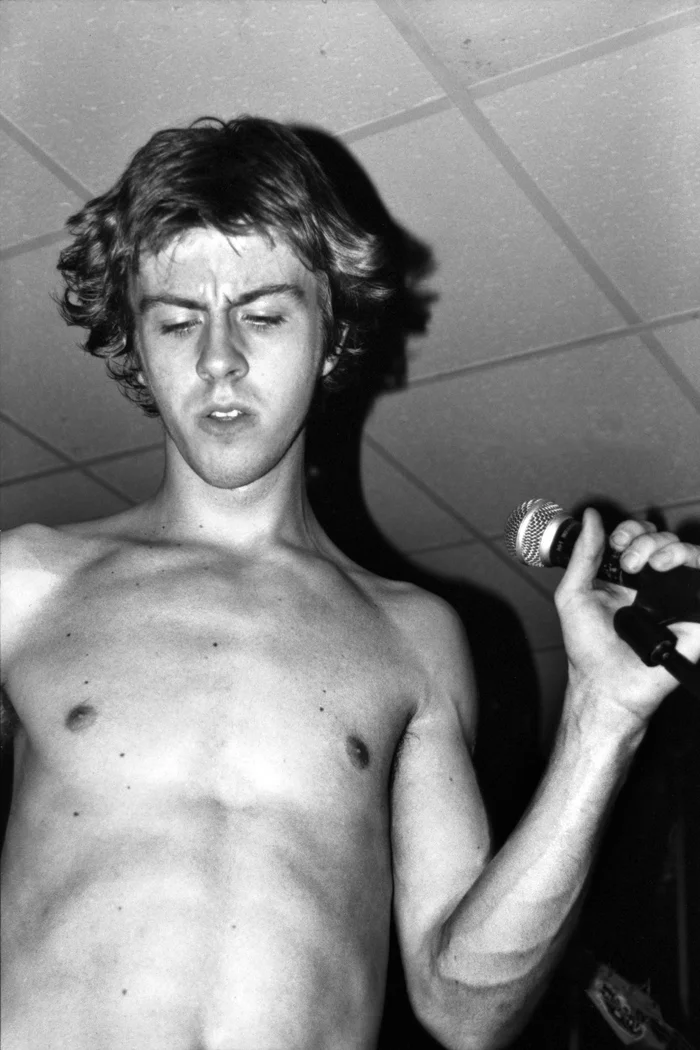

Lena Rosa Händle’s series Laughing Inverts is the most immediately arresting collection of photographs, as the works are dramatic, large-scale color images that face the entrance to the gallery. A combination of “intimate moments,” portraits, and candids depicting the subject caught in a moment of laughter, this series references Händle’s experiences in queer communities in a filmic, artfully composed way. On the adjacent wall to the right is Yulia Tikhomirova’s series Baltica, a mix of medium-scale black-and-white candids and smaller color landscapes that detail the artist’s experience upon her return to her hometown of Saint Petersburg. The black-and-white images capture moments from the artist’s history in the St. Petersburg punk scene with a Rolling-Stone-esque flair, divided into two diptychs separated by a smaller portrait. Considering the diptychs reveals a slight formal continuity between (and matching divide within) the two sets: the left photograph of each pair depicts a solitary figure completely absorbed in their relationship to the music we cannot hear, while the corresponding right take the opposite track, swarming the composition with overlapping hands and connecting motions.

Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

© Lena Rosa Händle, Su am Meer, Aus Laughing Inverts, 2008. Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

Hanna Putz’s large color analog photos on the wall to the right curiously comprise one of the more cohesive displays, despite not being specifically united under a series title. Using the format of the diptych more successfully than Tikhomirova, Putz’s pairings of grainy, slightly blurred images not only make sense but delight the eye with their uniting continuity of formal elements: the images on the outside depict chaotic motion and action, while the the photographs on the inside of each diptych focus on a single subject. Furthermore, the diptych on the right is particularly formally satisfying: the way the figures’ arms and legs are posed echo and rhyme with one another. The underlying conceit of juxtaposing two diptychs is similar to Tikhomirova’s own twinned images, but the latter’s work is diluted by the portrait and the smaller landscapes that compete for attention on her wall, while Putz smartly allows the two diptychs to command all of the viewer’s attention.

© Hanna_Putz_Untitled_Dyptich_04_2017. Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

© Ekaterina Anokhina, from 25 Weeks of Winter 2, 2013. Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

Anokhina’s display 25 Weeks of Winter has a mysterious narrative quality; her works actually take up one smaller wall and the remaining wall of the gallery, linking the two through one photograph laid on the ground in the corner to tell a melancholy, “heartsick” story from left to right. The bedroom interior of the stark color photograph in the corner is repeated in a black-and-white image on the first, smaller wall, allowing the viewer to ponder on the theme of heartsickness and loneliness: the black-and-white image has two subjects in bed, while the color photograph depicts a naked single figure bent over in clear discomfort. Once this room held life and connection and love, but no longer. The remaining works on the larger wall further this motif of loneliness, even dipping into images of desolation: the most rightward of the photographs are snapshots of a room in apparent disarray, with a broken chair, torn color tape, and broken bottles of liquor: once again, the place that held joy and happiness is empty.

Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

© Borjana_Ventzislavova. "It's just_me, 2012." Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

The most difficult aspect of I Dreamed We Were Alive is the so-called “meta-level” collection of color photographs by Borjana Ventzislavova that gives this exhibition its title. There are three works by Ventzislavova in total: one in the antechamber leading to the gallery, one on Anokhina’s wall, and one on Händle’s wall, functioning like interventions or punctuation in the statement that is I Dreamed We Were Alive. The works themselves are striking—the artist took photographs of harsh American desert landscapes, then edited in luminous neon text—but seem to function a bit like non sequiturs. The photograph with the text reading “It’s just me in there and I’m naked” is placed beside a work of Händle’s that contains a partially-exposed breast, but that connection just seems too on the nose. Overall, having an exhibition within and exhibition is a gamble, but it could have been more successful had more than three works been included.

Courtesy of Kunst Haus Wien.

Deborah Krieger is a freelance arts writer and future curator. She has written for Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art, Hyperallergic, and Title Magazine, and maintains her own arts and culture review blog i-on-the-arts.

I Dreamed We Were Alive is on view at Vienna's KUNSTHAUS WIEN through June 18th, 2017. Full details are available HERE.