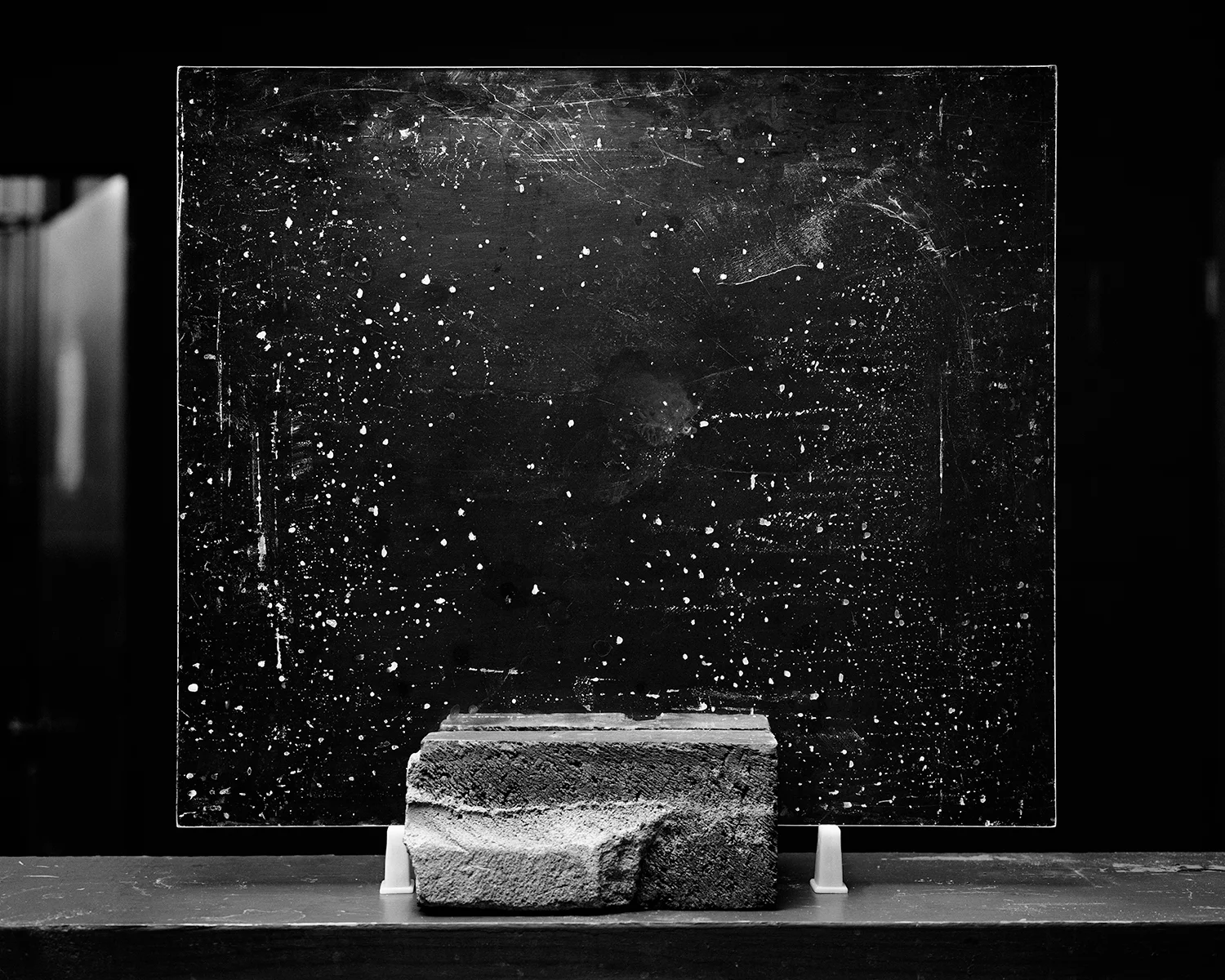

© Drew Nikonowicz. From the series Notes From Anywhere

Just one year since receiving his BFA in photography from the University of Missouri, Drew Nikonowicz has produced a prolific body of work that many would consider an accomplishment for photographers ten years his senior. In 2015, still an undergrad, the photographer snagged the coveted Aperture Prize for his series This World and Others Like It, and recently completed a one-year residency at Fabrica Research Centre in Italy.

Nikonowicz' mysterious, yet clearly defined practice explores aspects of fiction, reality and the history of photography. He shoots mostly large format black and white film, something unheard of for many photographers born after the creation of Photoshop. He imbues them with a current twist, often combining them with computer generated photographs to unite historic and contemporary technologies. At first glance, his pictures evoke early photographers like Ansel Adams and Edward Curtis in their monochromatic attention to the vastness of the American landscape. But while Adams and Curtis presented an optimistic, often idealized picture of promise and opportunity, Nikonowicz paints something a bit darker, layered with science fiction. I spoke with the photographer about his recent series This World and Others Like It, and its subchapter Notes From Anywhere.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

© Drew Nikonowicz. From the series Notes From Anywhere

Jon Feinstein: Your series Notes from Anywhere and This World and Others Like It feel like extensions of one another -- almost like a call and response.

Drew Nikonowicz: I completely agree. I definitely see them as living together. My approach while making TWAOLI was very different from my approach for Notes From Anywhere, but this was mostly influenced by where and when I made each project. I made TWAOLI as an undergraduate at the University of Missouri with limited opportunities to travel, but a lot of technological resources within my reach. So I worked on finding ways to combine analog and digital techniques to explore worlds that were out of my reach. Notes from Anywhere was made during a one year residency at Fabrica in Italy. While I was there I only had access to my 4x5, a bathroom for processing and a scanner, but I had frequent opportunities to explore and travel in Italy. So while I see them as being pieces of the same project, there are clear differences between the two approaches and by extension the two results.

Feinstein: How did the Fabrica residency impact your work?

Nikonowicz: When I accepted the invitation to work at Fabrica for a year I had never left the United States. I immediately found myself in a country where I didn’t speak the language and the general approach to most things is very different. I had to completely rework my approach as a photographer. I also no longer had the assignment-based structure of a university to force me to make work. I had to learn to keep myself motivated and give myself assignments. The experience definitely made me a much better photographer, both practically and intellectually.

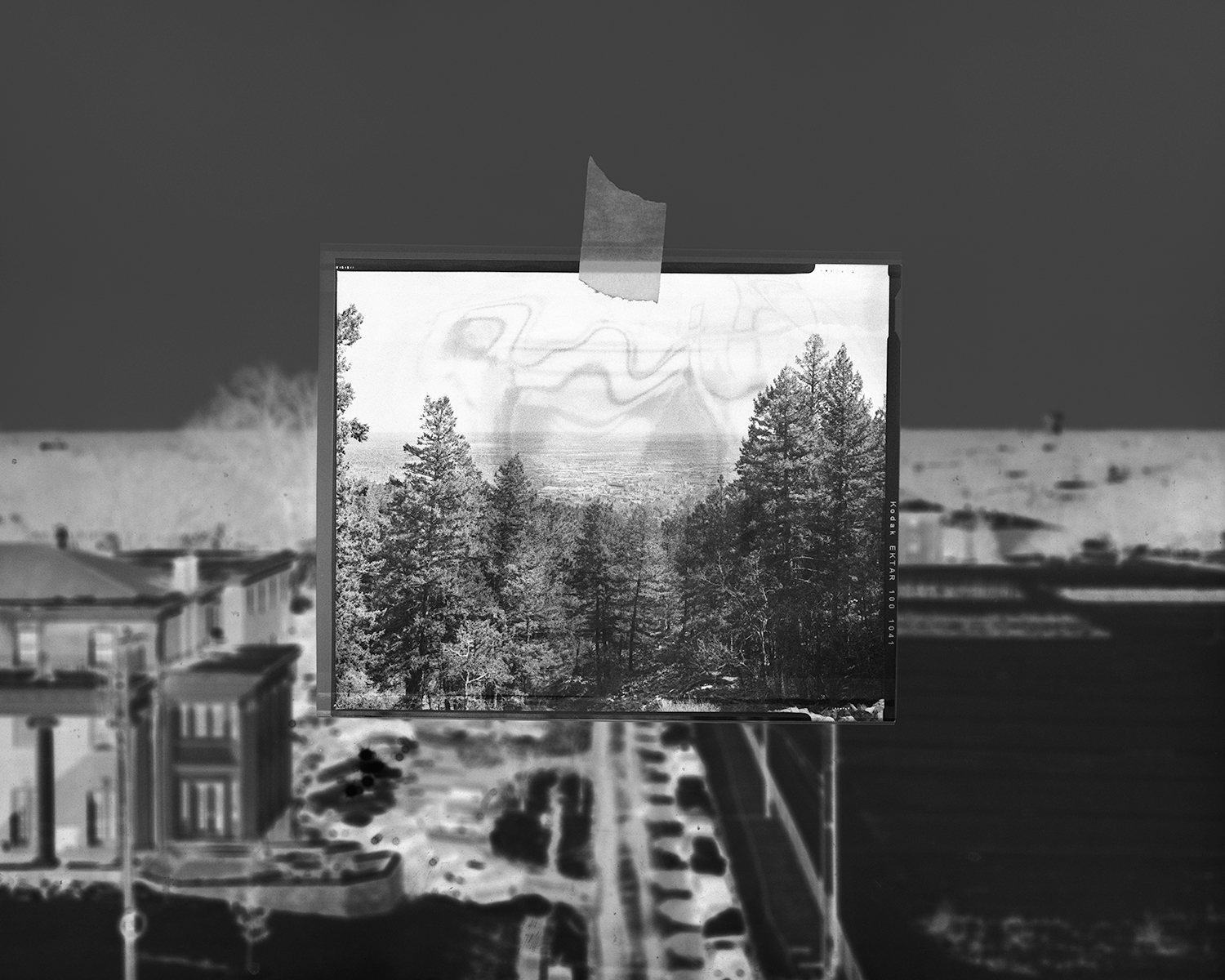

© Drew Nikonowicz. From the series The World and Others Like It

Feinstein: In your statement for Notes from Anywhere, you describe the work as documenting "moments of both direct and indirect experience....to search for places where the imaginary and real coalesce." What's the significance of the specific moments you are selecting?

Nikonowicz: While in the Fabrica Residency, I had the opportunity to travel regularly, so most of the photographs in Notes From Anywhere were found more than they were fabricated; the opposite of TWAOLI. I saw each image as a note or journal entry as I moved around the country. I tried to find scenes that were distinctly unique while also maintaining a level of anonymity to each location. In one of my notebooks I wrote a prompt to myself that said, “How do I photograph a highly unique place like Italy in a way that makes it look like it could be anywhere?” A window reflection, a small rock in my shoe, a screen in a cave. This was around the same time that I came up with the title for the sequence.

One point of departure while I was at Fabrica was reading Joan Fontcuberta’s book Pandora’s Camera. In the statement I am directly referencing a quote from Fontcuberta where he says, “and the spirit of Borges whispered to me that the boundary between the real and the imaginary is more imaginary than real.” Rather than separate these two worlds, I tried to reinforce the fact that there is no difference between the worlds I imagine and the worlds I physically occupy. In the end, my mind is constructing both.

© Drew Nikonowicz. From the series Notes From Anywhere

Feinstein: You were born after Photoshop, as "digitally native" as it gets, yet I understand that you shoot 4x5, use many analog and traditional means. Can you talk a bit about your relationship to photography and technology and how it informs your work?

Nikonowicz: As a child, I was exploring new worlds through video games and my computer on the same days that I went outside and created my own adventures in the woods. These two kinds of experiences operate side by side in my life. Our lives online and offline have become completely inseparable. The only difference for people born after the internet, like myself, is that this feels more natural. To that effect, I have always enjoyed the ability to interchange the way I build and experience things. Photography is the same way for me - each image is a complex construction that I have to try and control and manipulate. I prefer to use a 4x5 because it helps me slow down and shoot more deliberately, but for TWAOLI I also spent time creating computer generated images. In this way, how I approach my work very much reflects my actual relationship to technology.

© Drew Nikonowiz. From the series Notes From Anywhere

Feinstein: Do you see age-old notions of Manifest Destiny fitting into your current conversations?

Nikonowicz: For now, we are positioned between the last human-led expedition and one to happen in the future. Conceivably it will be a journey to Mars, or to the moon. I hope if someone swings back by the moon they pick up the Hasselblad cameras we left there during the Apollo missions.

In the meantime, I believe the frontier we have to explore exists through advancements in technology. Everything from the infinite and procedurally generated worlds of Minecraft, to the rise and use of gene-editing and everything in between. The frontiers we have today are hidden away right in front of us in the things we don’t yet understand. Regardless of what we choose to explore, I don’t think we do it out of divine right. However I do believe that the continued exploration and pursuit of everything within space and time is unstoppable, even if it’s not always justified.

© Drew Nikonowicz. From the series This World and Others Like It

Feinstein: What draws you to shoot exclusively in black and white? Could these projects function as color photographs?

Nikonowicz: With TWAOLI I chose to use b&w so I could create a level playing field between the analog photographs and the computer generated photographs. If the two kinds of images were immediately recognizably different, there would be no space for the viewer to actively consider their relationship. I also see the computer generated photographs as images of an alternate frontier, so I felt it was a nice way to reference back to 19th century frontier photographers such as Timothy O’Sullivan. When I arrived in Italy I considered shooting the new series in color, but when I decided to keep working on the same project I wanted to maintain that visual consistency. It also allowed me to continue to process the film myself (now in a bathroom rather than a proper darkroom) and keep the project financially feasible. Another version of this work with a different visual style could absolutely exist through color photographs. I do not think this specific iteration of the project would function effectively in color however.

© Drew Nikonowicz. From the series This World and Others Like It

Feinstein: I sense a tangential relationship to Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle with some of this work. Do you agree?

Nikonowicz: Yes. Although I would make a slightly different argument. Your question, and thinking about Debord’s ideas reminds me of this quote from Luigi Ghirri.

“The distinction between true and false is increasingly difficult to make, and it seems

progressively impossible to get beyond the immediately visible.”

Ghirri wrote this in 1979, but I think the idea is even more true now than it might have been then. Debord suggests that our “direct” experiences have been replaced by representations, but I disagree. Instead I would say that we create representations (typically photographs) as a way to validate our experiences. We have delegated our memory and our capacity to verify our existence to the camera.

© Drew Nikonowicz. From the series Notes From Anywhere

Feinstein: Who else are you looking at right now? What outside of photography inspiring how you think about your practice?

Nikonowicz: Right now I have begun research and work on a brand new project so the things I’m looking at are quite specific, and still under wraps. A few months ago I had the opportunity to go to the Netherlands for a few days. While I was there I saw Chrystel Lebas’ wonderful project Field Studies at the Huis Marseille that has stayed with me since I saw it. I also managed to see Ren Hang and Hiroshi Sugimoto prints over at FOAM, which was like a religious experience for me. Outside of photography, I try to always have a book I’m reading that’s not photo related.

The most recent book I finished was Chuck Klosterman’s But What if We’re Wrong and it blew me away. I think the books I read that aren’t photo related influence my practice much more than the ones that are.

© Drew Nikonowicz from This World and Others Like It

Feinstein: Can you tell me a bit about your overall process in making + editing your work?

Nikonowicz: All the photographs I make are a combination of places I have been and things that excited or interested me. I try to do my best to make every image that comes to my mind, or at the very least write the idea down for later. Usually I refine my ideas and process at the editing table. I make a large number of photographs, spend time with them and think about how they’re working, then repeat. I had a professor in college tell me that you cannot create and curate at the same time. It’s integral to my practice that I don’t talk myself out of ideas, and I prevent that by shooting my ideas before I can stop myself. At a certain point photography is a numbers game, and the more players you have to choose from, the better your starting lineup will be.

Where are you personally in both of these projects?

I think every photograph that isn’t a straight landscape has a piece of me in it. Like every photographer, I have an anecdote I could tell about every image - the memory of making that photograph. Most of the images are studio constructions in one way or another. So in a way I am present through the objects and scenes I build. In Notes, there are also images where I am literally showing my hand. I try to reveal my presence wherever I can.

© Drew Nikonowicz from This World and Others Like It

© Drew Nikonowicz from This World and Others Like It

©Drew Nikonowicz from Notes From Anywhere

Bio: Drew Nikonowicz (born in St. Louis Missouri, 1993) earned a BFA degree from the University of Missouri - Columbia in 2016. His work employs analog photographic processes as well as computer simulations to deal with exploration and experience in contemporary culture. He has exhibited both nationally and internationally. In 2015 he received the Aperture Portfolio Prize and the Lenscratch Student Prize. Nikonowicz recently completed a one-year residency at Fabrica Research Centre in Italy, and now lives and works in the United States.