© Pace/Wirtz

Beginning in the 1980s, theorists including Allan Sekula and Jon Tagg initiated critical work that analyzed the organization, purpose, and consumption of photographic archives. In doing so, they implicated the medium as a tool of state surveillance and control deployed against often vulnerable populations.

The points asserted by Sekula and Tagg about photographs within an archival setting encouraged numerous artists to utilize archives as the source or focus of substantive work. Those now-familiar lines of inquiry are widened, and the interpretation of archival material in photographic form expanded in Recollected: Photography and the Archive, a group installation that was on view at the Fine Arts Gallery at San Francisco State University through November 16.

Exhibition Review by Roula Seikaly

British Bomber 8-22-40 © Pace / Wirtz

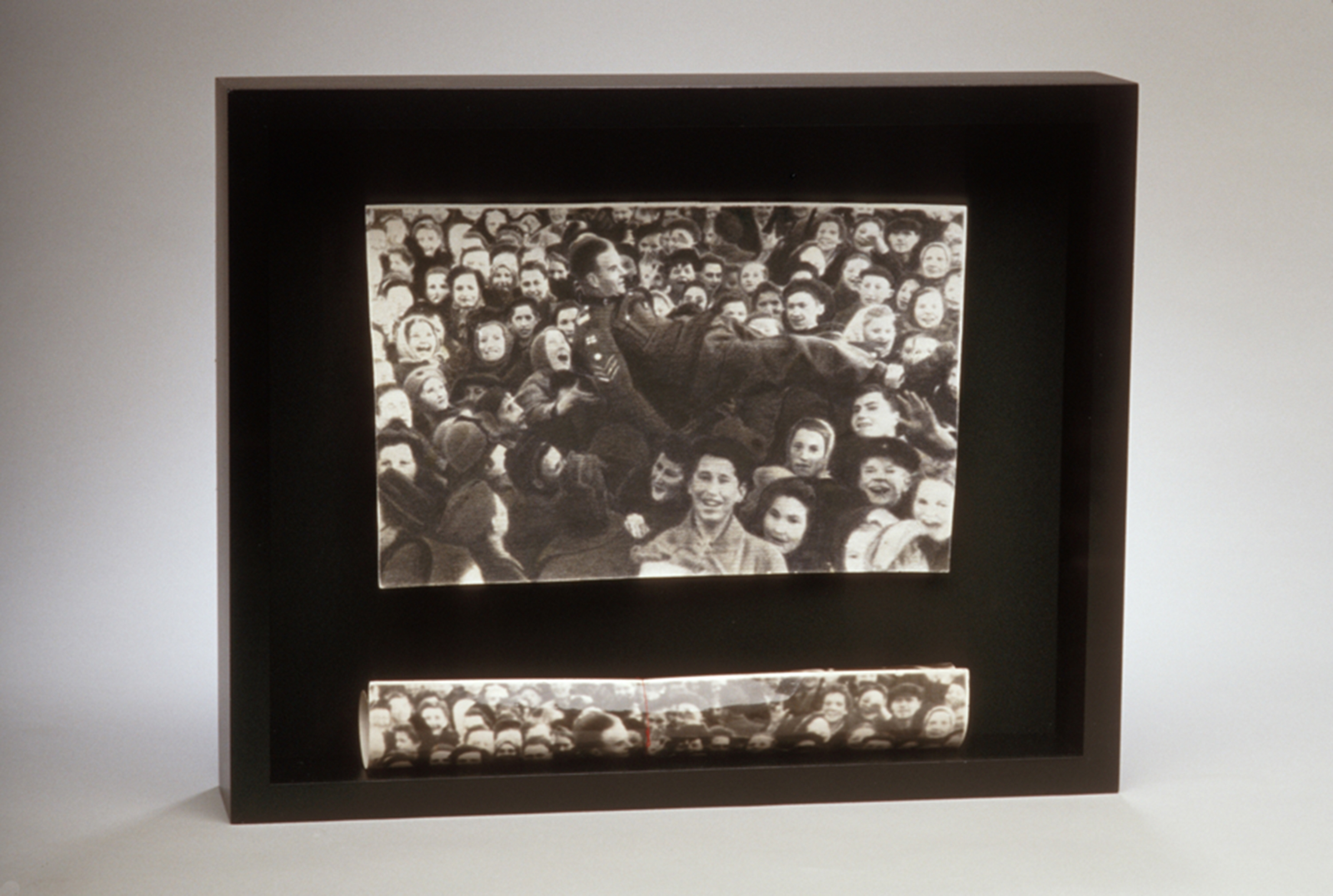

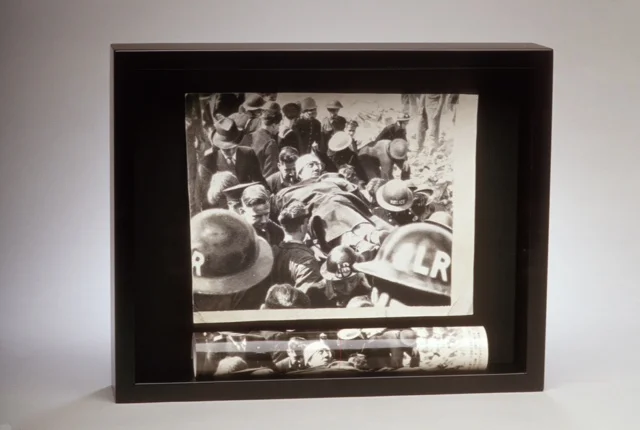

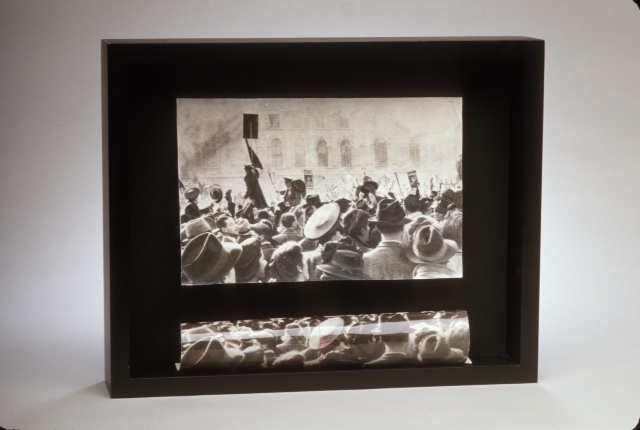

Individual pieces or long form projects that sharpen earlier critical analysis of archives as seemingly impenetrable, authoritative data sets include the work of collaborators David Pace and Stephen Wirtz, multimedia artist and educator Tina Takemoto, Nigel Poor, and Ian Everard. For WIRE/PHOTO, Pace/Wirtz work with World War II images that were originally transmitted by wire or radio waves for reproduction by mass media outlets. The duo scans vintage images and then enlarges the digital files to produce new compositions. This radical modification magnifies the physical imperfections of both the original and scanned images, and highlights the ideological flaws inherent to the conduct and portrayal of war via photographic means.

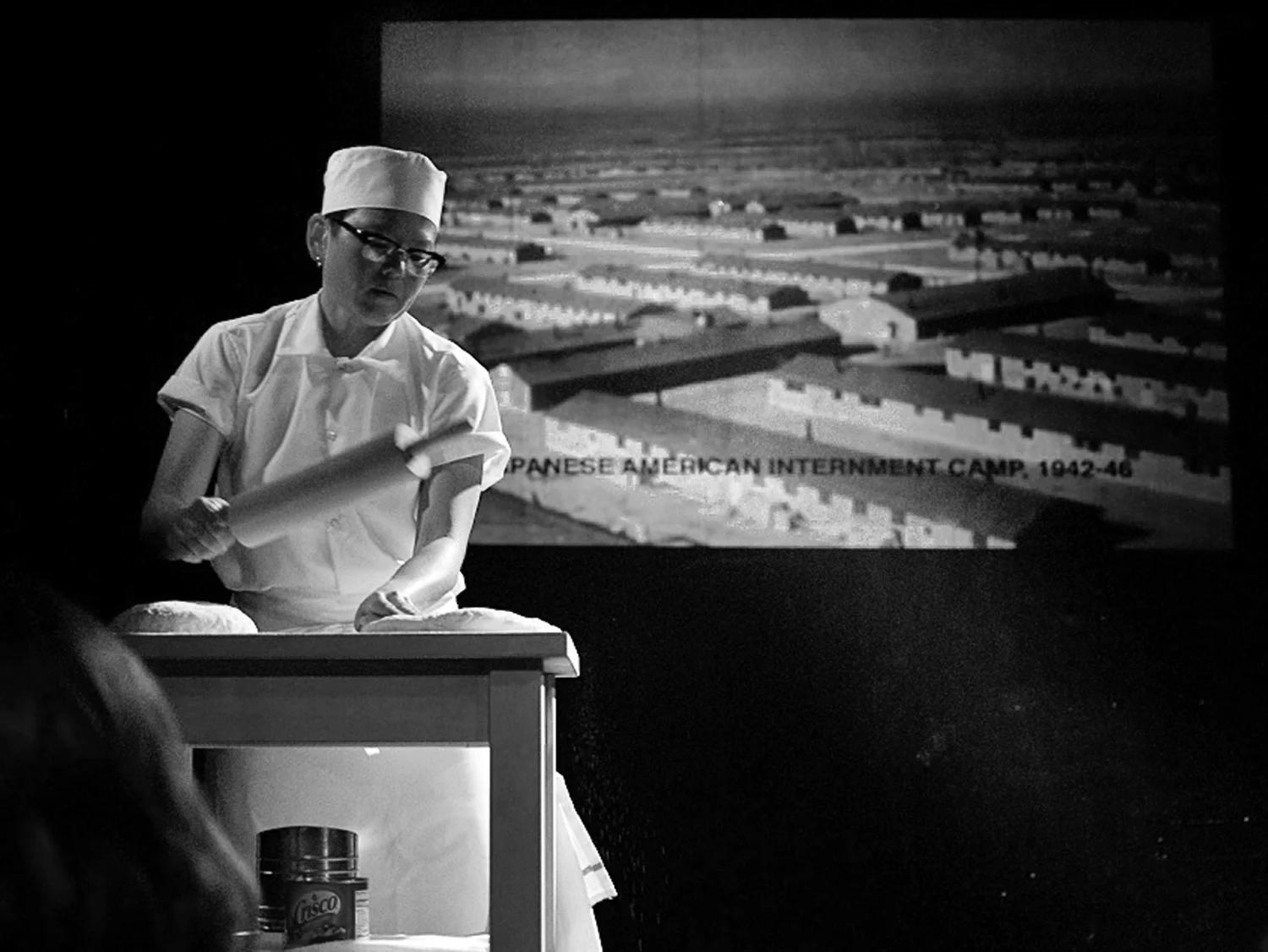

Takemoto’s experimental film Looking for Jiro (2011) liberates her subject - Jiro Onuma, a queer Japanese immigrant who arrived in the United States in the 1920s - from the context of internment that he and more than 110,000 Japanese Americans endured during World War II. Takemoto channels Jiro, envisioning his work as an industrial baker as as subversive act of personal and sexual liberation. Dressed in a baker’s hat and apron, Takemoto lovingly prepares and then fists the loaves of fresh bread, an action that honors Onuma’s public commitment to productivity in a surveillance-driven environment in which he had to prove his patriotism, and a private pleasure possibly shared with a partner. Takemoto’s work within San Francisco’s GLBT Archive addresses the question “how does one live a life that society forbids,” when that life is criminalized both for one’s ethnicity and sexual identity.

Tina Takemoto's Looking For Jiro. Photo courtesy of Maxwell Leung

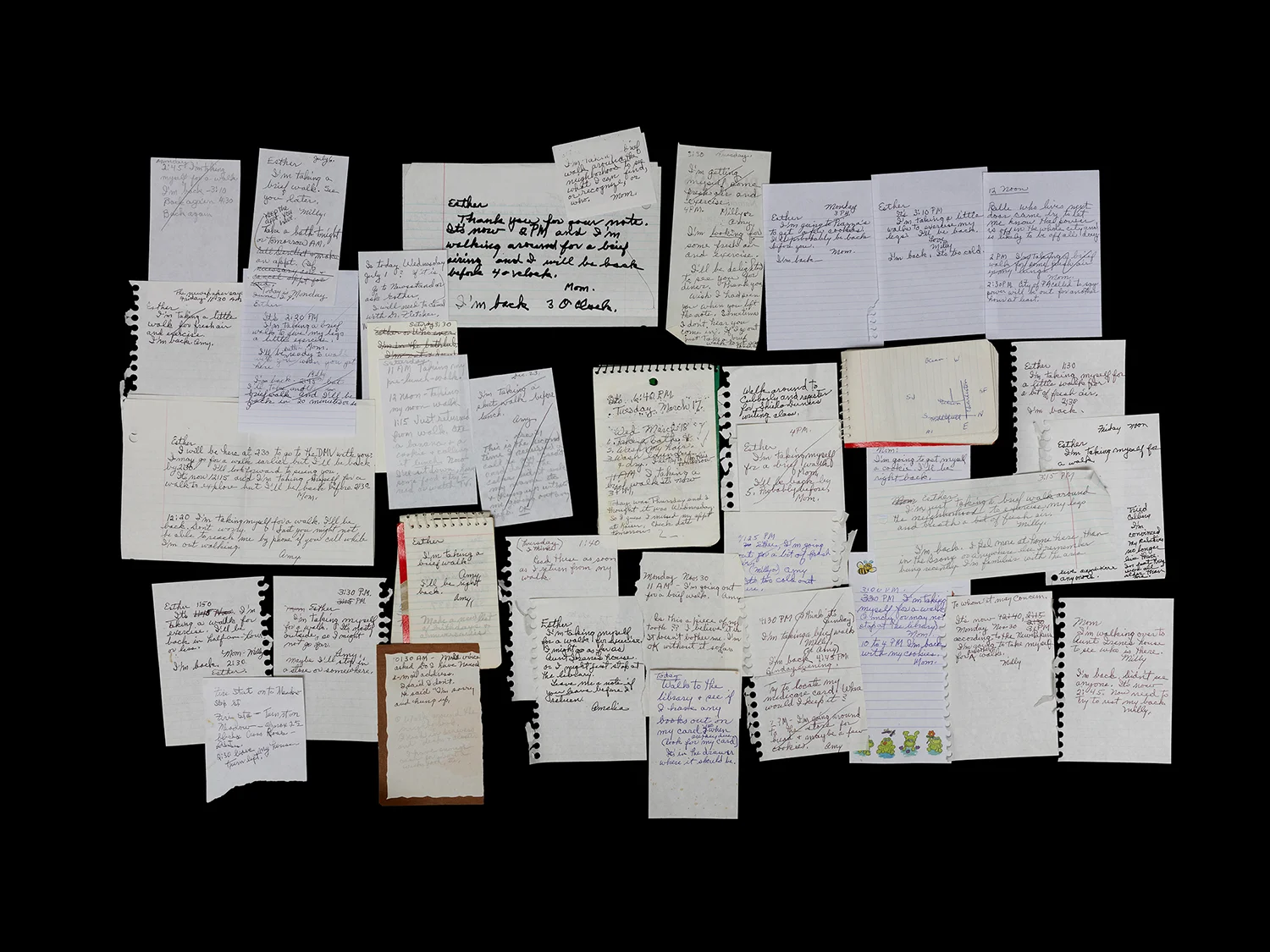

Taking a Walk © Kija Lucas

In the editorial essay that introduces a 2010 Photographies volume comprising current work on photography, archive, and memory, authors Karen Cross and Julie Peck note that while Sekula and Tagg’s work advanced our understanding of how photographs operate within archives, their analysis focuses only on archives as material manifestations of the state’s repressive powers. On an immediate level, archives may be understood as measures of personal experience and identity. Kija Lucas’s effort to capture her grandmother’s day-to-day life ahead of Alzheimer’s Disease thieving progress represents archiving as a loving act of resistance. For Collections from Sundown (2013-present), Lucas photographed the notes her grandmother made and the objects she collected over the course of several years as her illness advanced. The notes remind Lucas’s grandmother of what she has done, or will do, as an otherwise easy mental operation becomes increasingly difficult. Lucas’’s still lifes are observational, and read like field notes from a poignant and devastating research project.

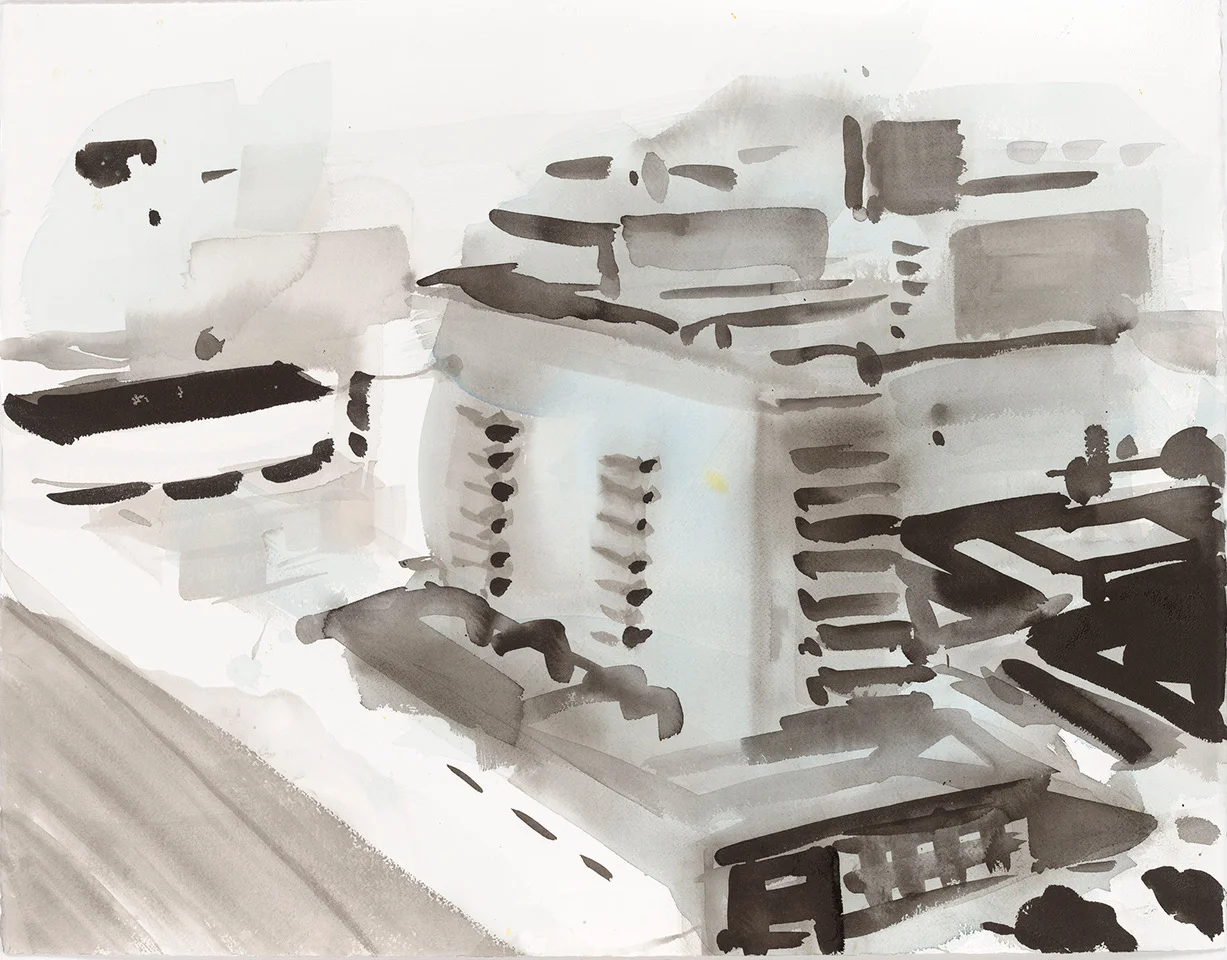

Karl Marx Allee Buildings © Pamela WIlsonn-Ryckman

Photographs functions as both materials within and means of interrogating archives. In their respective practices, Pamela Wilson-Ryckman, Hung Liu, and Chris Dorosz use photographs as primary sources, yet critique archives from a painterly perspective. Drawing from a cache of 1970s photographs that document architecture in Soviet-controlled East Germany, Wilson- Ryckman portrays totalitarian bureaucracy through minimal watercolor compositions. The austere and wholly intimidating structures recreated with simple, Chinese-landscape influenced brushstrokes read as wistful, memory-laden, and harmless. Hung Liu’s Migrant Mother (2015) draws from Dorothea Lange’s iconic image that bears the same name, and humanely relates her experience of war and famine in China to the degradations thousands of Americans faced during the Great Depression.

Migrant Mother, 2015 © Hung Liu. Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Chris Dorosz' Stasis series engages the internet - inarguably the largest and most unruly archive humans have constructed thus far - to measure a creeping numbness to worldwide misery. Three-dimensional objects that visually slip between paintings and sculptures are stripped of contextualizing references, so that at a distance viewers see a wailing adult holding an injured child and upon looking closer, layers of blended paint drops. As Dorosz blurs the terms of representational media, we may be left wondering to what degree the image glut we’re exposed to every day hobbles our responses to suffering at home and abroad.

Damascus © Chris Dorosz

While divergent in their subject matter and means of execution, the work of Wilson-Ryckman, Liu, and Dorosz demonstrate the potency of archival material to artists working outside of lens-based practices and bring diversity to an otherwise photo-driven installation.

Recollected: Photography and the Archive began as a class project assigned to graduate and undergraduate students enrolled in SF State’s Fine Arts Gallery now-emeritus director Mark Johnson’s Spring 2017 ART 619 course. Guided by curators Sharon Bliss and Kevin B. Chen, the students worked within specific guidelines - pieces produced by artists who live or have significant ties to the Bay Area - and suggested a range of objects reflecting diverse practices. The result is an economic and beautifully organized presentation of media forms that engage past and present discussions of what archives are and how they function, and what insights may be drawn from them moving forward.