© Nathaniel Ward

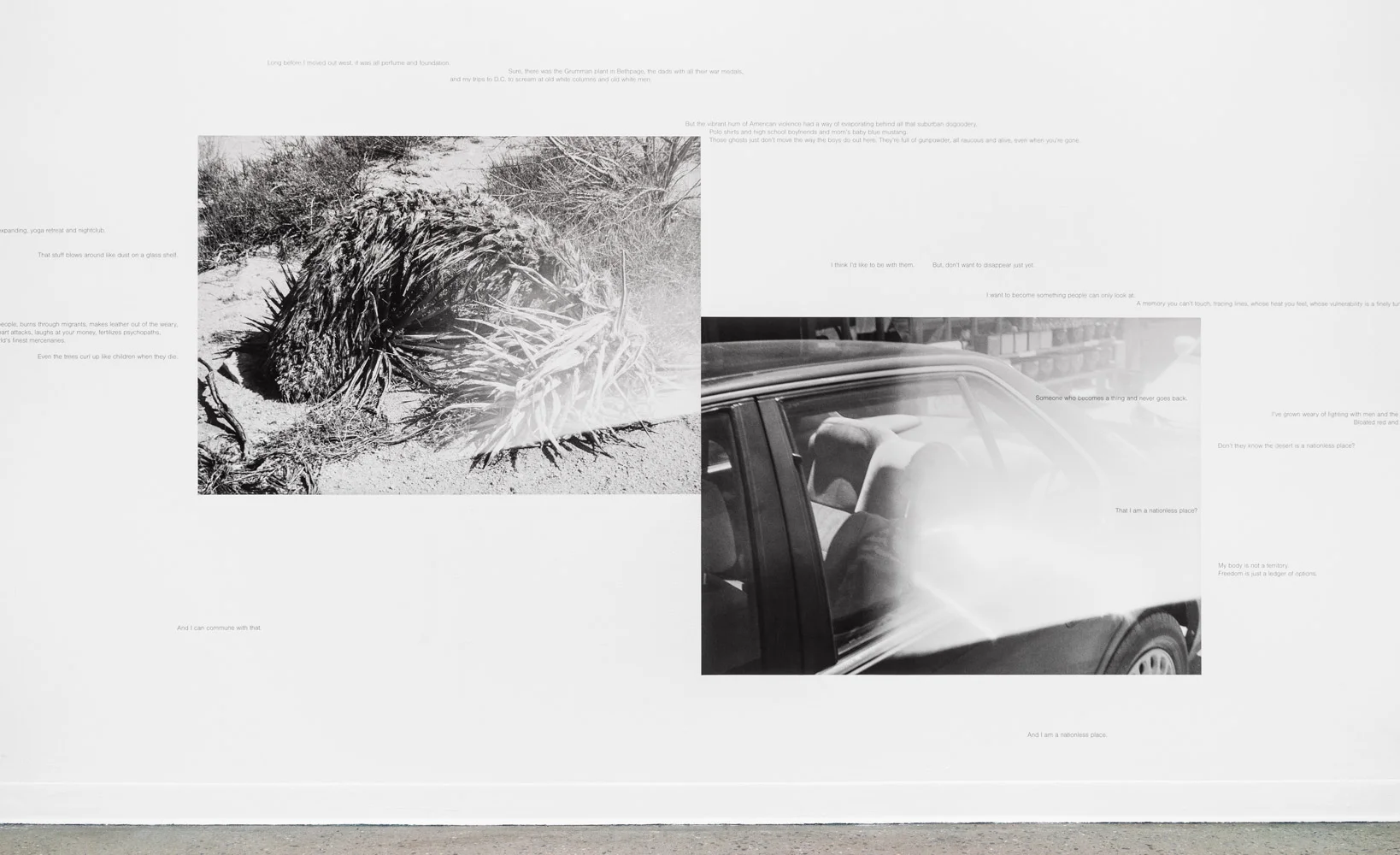

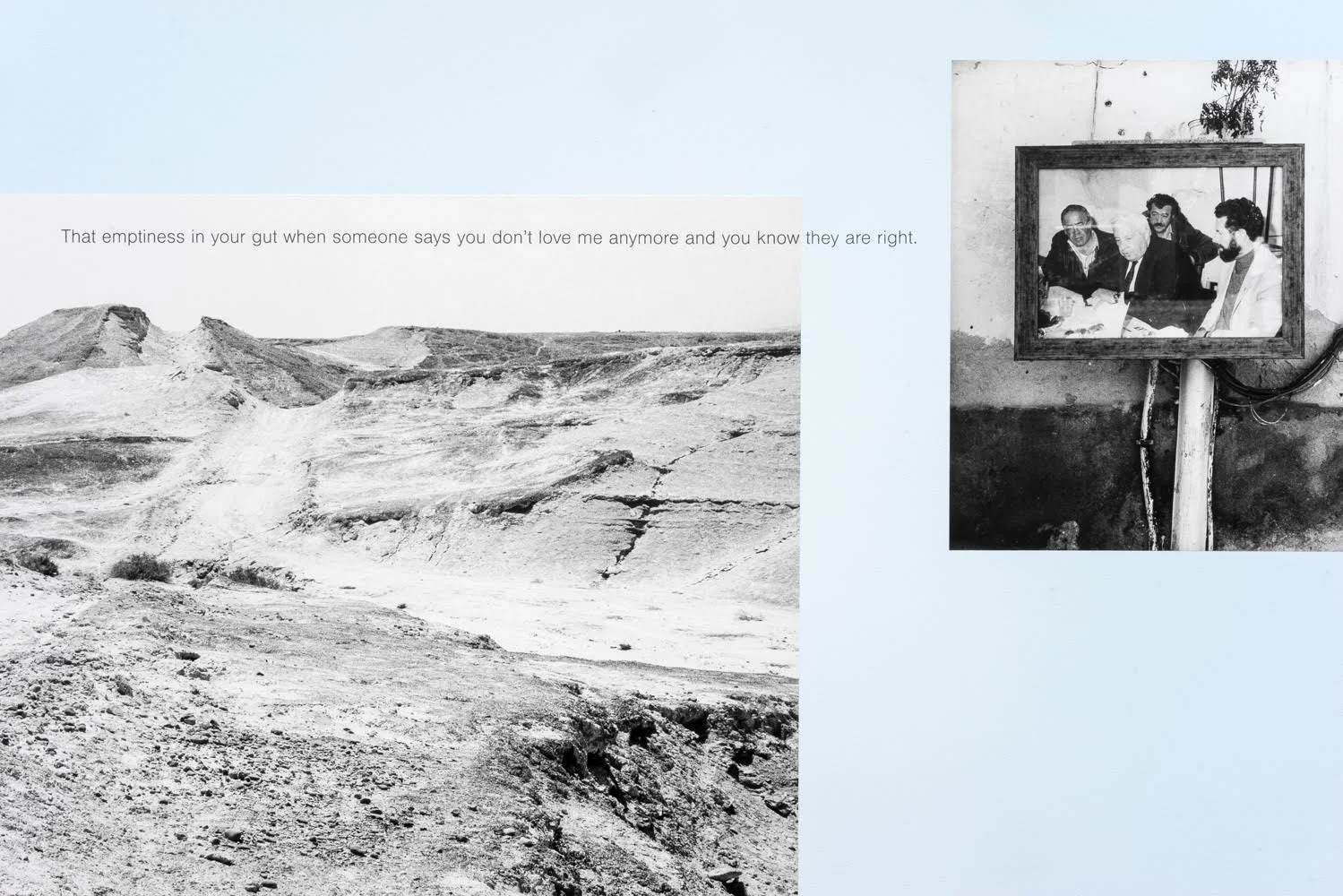

He may not tell you this directly, but Nathaniel Ward's photographs are about the subtlety of defeat. They are brimming with quiet, often painful metaphors, buried as footnotes in photos of people and the land. From the ghostly large format color photographs of hallways, classrooms and bathrooms in American schools Ward made a decade ago, to To Turn the Mountains into Glass, politically agnostic black and white pictures made while traversing Israel's charged landscape, his work is riddled with introspective pause. And it's consistently quite beautiful. Ward's latest exhibition, A Nationless Place, on view through March, 2018 at the Ford Foundation Gallery at New York Live Arts adds a new layer to his methodologies by integrating sweeping swatches of text beside his photos of sometimes-confusing slices of landscape and human experience. Unlike explanatory "exhibition text" you might expect in a themed group-show retrospective, it functions as a piece of the art unto itself. I spoke with Ward to learn more.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

© Nathaniel Ward

Jon Feinstein: This is the first time I've seen you weaving text so organically into your work. It really transcends the traditional artist statement we've come to expect.

Nathaniel Ward: I've always been a bit afraid to write. I used to have terrible anxiety about it in school. Writing artist statements kind of changed that for me. It's a form of writing bound by so many rules and limitations that it started to feel safe. Once you get it, you can just churn them out. I mean it's so rote that there are more than a few artist statement generators out there (see http://artybollocks.com/ for example).

The pleasure of that safety sucks. It's all tell and no show. I got increasingly bored with the style, the repetitive formalism, and the reductive academic signaling. I wanted writing that complicated and intensified the experience of my photographs.

I started playing with my artist statements; trying more lyrical approaches, thinking about allegory and fictive potential, about not giving it all away in three paragraphs, using simple language, and about building mystery. They were bad artist statements but they became something else.

© Nathaniel Ward

Feinstein: Have you secretly written prose poetry before?

Ward: About two years ago, I was experimenting with a small artist book. I took one of these mutant artist statements, which at that point had evolved into a sparse, first-person, character-driven, short story, and wove it through the images in the book. The pictures became the stage and the characters. The text became a kind of script. I got really interested in what the photographs could reveal about the text and what the text could augment in the photographs. That book evolved into another installation I recently opened as a part of the Brooklyn Rail's Occupy Mana at Mana Contemporary

The photographs in A Nationless Place are already kind of mysterious. They beg for more information. Given that context is abstracted and obscured by various photographic phenomena and content is unified by signs of a particular place but not a particular person, I constructed the written narrative around the kind of person that might see that landscape, and those things, in that way.

I think the default desire of most people looking at these kinds of photographs would be to ask "where am I, why should I look at this thing, and what made all these bright squiggles and hazy bits?" The text shifts the photographic question towards something more along the lines of "What could happen here next?"

© Nathaniel Ward

Feinstein: You describe this work as a fictional narrative. How much of it plays on your own story or internal monologue?

Ward: Actually a great deal. Just not so directly. I guess when your write a certain kind of realist fiction it's especially true that you make work out of what you know. You can take your own lived experience and change just enough so the work becomes a new thing.

There is a lot of lore in my family about the Mojave desert. A lot of momentous, failing, fracture located there and a deep longing for people who lost themselves in that place. I felt like the photographs just scratched the absolute surface of making that desert specific.

We're humans. So, we need something human to make a place matter; to make a place meaningful. I drew directly on some highly specific family history with an aim to make that inhospitable and monumental space a bit more habitable and a bit more human in scale.

© Nathaniel Ward

Feinstein: Is this about escapism?

Ward: Yes. And self-sovereignty. And geo-political dislocation. And conflict fatigue. And unbridgeable interpersonal distance. And recognizing disappearance as a personal and political weapon. (Maybe delete your Facebook account?) And abject satisfaction (I mean, can you imagine if you deleted your Facebook account?). And the global history of the desert as a refuge from the prying, thieving, advertising, dictating, seducing, manipulating, momentarily satisfying, or otherwise invasive tendencies of a dominant culture (political or otherwise). A refuge for better or worse. Sometimes better. Often worse. And violence on a minute and monumental scale.

Feinstein: Does our current political climate play into how you're thinking about this work?

Ward: I'm less drawn to ideas about our current political climate and much more curious about how un-current and un-new this whole political era feels. Are the politics an anachronism or are we just playing ourselves? Whether the character in this piece found the desert in 1974 or 2017, do you think her core motivations would change?

Feinstein: What's the significance of the Mojave desert?

Ward: Allegorical or otherwise? I mean, it's a place in America where you can play-act at escapism and it's also a place where people actually, and fully, disappear. It's rich with all sorts of intertwined and fully-visible American histories. The ruins of people and places take a long time to decay in that arid climate.

Screenshot of A New Nothing

Feinstein: You also run the artist-conversation site A New Nothing with Ben Alper. Has the drive to foster collaboration between artists had an impact on your own practice?

Ward: Absolutely. The practice of fostering collaboration, either in my own conversation with Ben Alper or in the pairing of other artists together, has always been about a curiosity to see what photography can do. How am I going to continue to be surprised by pictures and what people do with them? I think A New Nothing and my broader practice in general are both motivated by this strange and ever-seeking optimism about photography.

Feinstein: Do you see it having an influence on A Nationless Place?

Ward: Integrating text directly with photographs and thinking more responsively about the specific space of the exhibition for A Nationless Place was just another way to try to work that central question more broadly. What can this space do? What can the physical movement of people through viewing images and reading text do? What can photography do when the accompanying text provides more questions than answers?

© Nathaniel Ward

Feinstein: NY Live Arts uses the following language to discuss this work. Can you speak more about this sense of rhythm and integration they're referring to?

"a way to choreograph the movement of viewers through formal constructions of visual rhythm and narrative flow in order to expressly connect with the performance based mission of New York Live Arts"

Ward: There are lines that flow from one image to another and an installation that draws you up and down and across the room from left to right. There is a bit of call and response rhythm between the scale of the text and the much larger scale of the images that, if you are trying to fully see both, requires you to move back and forth from the wall. There is an alternation of primarily dark images with primarily light images. And, the text itself is insistently rhythmic; punctuated with pauses and driven by a cadence that moves at it's own pace.

The work is installed in a space filled with some of the most talented contemporary dance professionals in the world. I am not a choreographer. But, I felt it would have been a mistake not to consider the physical, embodied, engagement these large images and sprawling text allow.

There is a performance in looking at art on a wall. I want to make that performance more palpable and more self-reflexive.

Feinstein: Tell me about the line "The desert did try to kill me."

Ward: In 2012, I was in a plane that was on fire above Palm Springs. Not much is scarier than a rapidly descending airplane filled with more than 100 people traveling in total silence towards tarmac. But, I didn't want the specificity of that story. I wanted to establish a sensibility and create a psychological space upon which I could build the broader narrative of the piece. Besides, there are plenty of more interesting ways to die in the desert than courtesy of American Airlines.

© Nathaniel Ward

Feinstein: You take a very non-linear approach to how the exhibition is installed, and similarly how the text is displayed. How/why is this important to the narrative you're building?

I think people need space to breathe. In addition to what I was thinking about in terms of choreography, the wall is really important as negative space. It's something like the way a blank page in a photo book gives you the sense that you are entering a new section or chapter or a slightly different organization of ideas. There is physical space you have to cross in order to get to the next line. I like that I can build in more space for internal reflection.

Feinstein: NY Live Arts isn't your typical gallery/museum exhibition space, at least to my knowledge. can you talk about why it's suited particularly well for this work?

Ward: The thing I really like best about the space, aside from the aforementioned relationship to performance, is that it is a fully public space that, in and of itself, is intended as a refuge for a kind of escape from the rigors of rational existence in New York City. New York Live Arts and The Ford Foundation Live Gallery are a place to expand your critical and compassionate understandings of human experience. If I can participate in that, even in some small way, I feel like my work is doing its job.

© Nathaniel Ward