Self Portrait as Barron, 2017 © Jayson Bimber

In his ongoing series The Aristocrats, photo-based artist Jayson Bimber combines crude digital retouching with references to art-historical tableaus as a means to critique systems of wealth in the United States and abroad. He scans found images from fashion magazines and advertisements, creating montages that are as equally unsettling as they are seductive. Bimber's techniques highlight an umbrella of contemporary concerns ranging from political corruption to sinister puppeteering in the upper echelons of the commercial fine art market. Like the famous joke "The Aristocrats" from which this series' title is derived, it intentionally lacks a punchline or true narrative structure, bringing to light the absurdity of its content, in essence, a "joke about jokes."

I spoke with Bimber to learn more about his process and ideas.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

Lounge, 2016 © Jayson Bimber

Jon Feinstein: Before we get into the larger project, I need to know -- what's the story behind your self portrait as Barron Trump? It's funny in a way, but I find it incredibly unsettling.

Jayson Bimber: Shortly after the election, a colleague, Austin Brady sent me a gallery of those incredible Trump family photographs taken in their residence and said, “Isn’t this your art?” They are awesome and bad technically and totally look like what I try to make. I saw that portrait of stoic Barron sitting on the FAO Schwartz lion and just felt like I could relate to him, like neither of us asked for this or wanted to be in this situation and we aren’t happy about it, but here we are trying so hard to put our best face forward. I was able to find a ginormous version of that file online and it quickly became a therapeutic post-election creative outlet, coming to terms with President Trump.

Feinstein: I hear you. In so many ways, he's just an innocent bystander of this larger mess. How did this series begin?

Bimber: I had been looking for a line of narrative work that would allow me to get back to the working methods I was employing in graduate school. That is an appropriation of pictures, digital collage, and art historical references. I also vaguely wanted to satirize images of wealth in some way. The first image was going to be a rearing horse and its owner. That didn’t get very far, I was afraid it wasn’t actually critiquing anything.

Feinstein: You use a Talking Heads quote in your artist statement. It feels so keyed into this series -- the grotesque gloss that's entrenched in consumer culture and our day-to day lives. Can you elaborate on its significance to you and to the series?

Bimber: There are a few things that go into quoting that. First that song, [Nothing But] Flowers, is amazing, I love its irony. David Byrne is saying that a world without materialism would be paradise but doing so in such a satirical way. It is something I really strive for. It takes the hokeyness of, Joni Mitchell’s Big Yellow Taxi “They paved paradise and put up a parking lot” and makes it “If this is paradise / I wish I had a lawnmower.” I think that turn is really creative and powerful.

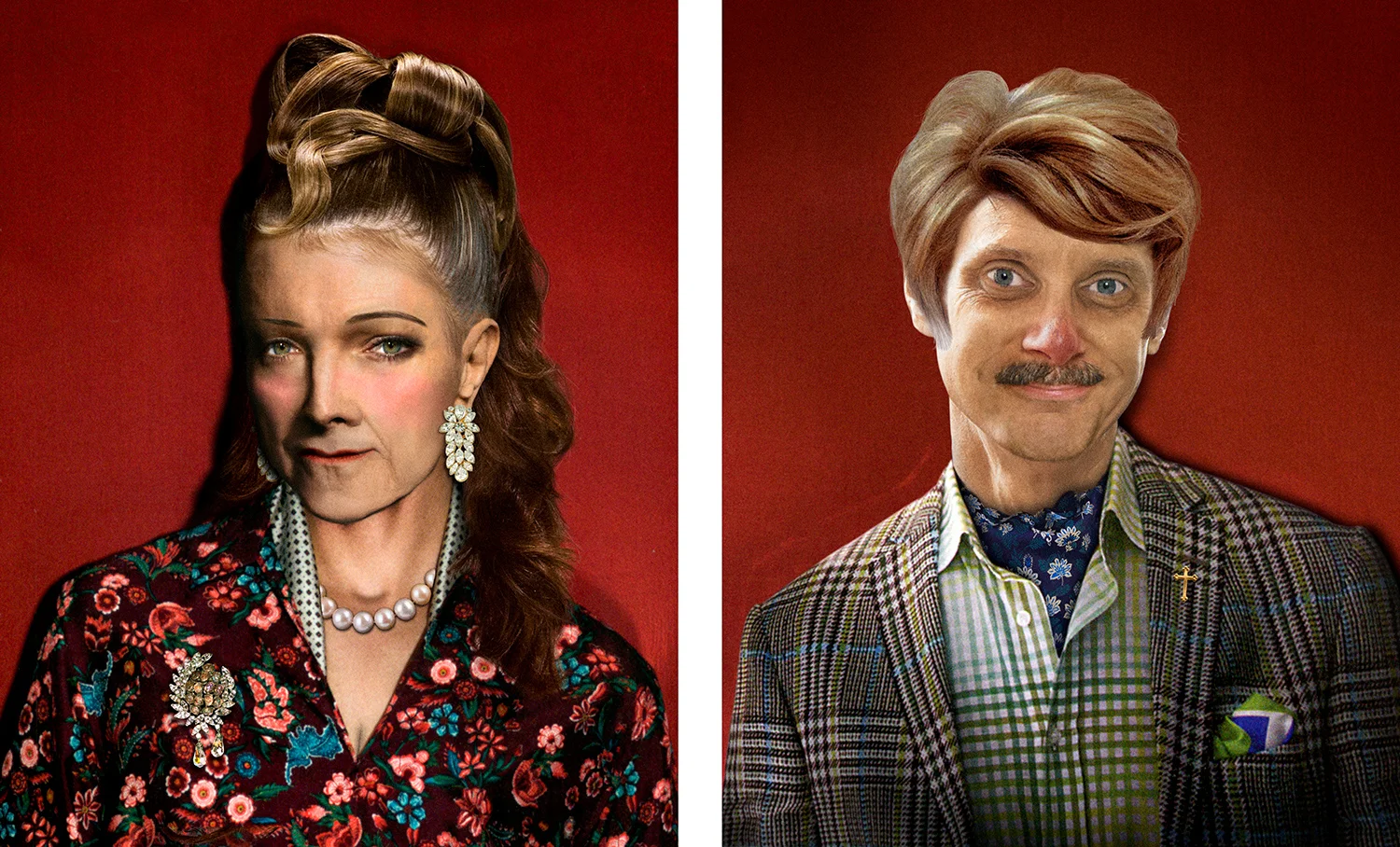

That specific line, “And as things fell apart / Nobody paid much attention” is used as an epigraph in Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho. I had read an interview with Bret Easton Ellis where he discussed using the descriptions of designer fashions in American Psycho as a way to both highlight our glossed over acceptance of consumerism and high fashion and to add an absurdity to the characters. Like if you were to composite the descriptions of Patrick Bateman’s attire he would look ridiculous. This is conceptually the jumping off point for my diptych Mrs. & Mr. Van Guilder. So using that line is a way for me to begin to introduce both those concepts to the viewer.

Paramour, 2015 © Jayson Bimber

Van Guilders, 2014 © Jayson Bimber

Feinstein: I first saw your work when you submitted to our online group show "Alternative Facts" earlier this year. So many of the images in this series address that idea -- each image functions as its own kind of alternative fact, they also function as a means of pulling these apart. Would you agree?

Bimber: Absolutely. I think at an underlying level my interest in photography derives itself from questioning the truth claim of the medium. As an artist I strive to give the viewer an opportunity to witness the pulling apart of an images authenticity.

This work plays pretty hard with the concepts of stereotype. I really have no idea at all what its like at all to be wealthy, so I imagine and stereotype and invite my viewer to play along. In the case of my pictures, these aren’t really people, and they certainly aren’t in any sense real. They are composites, highly posed and manipulated. The images are photographic but fall apart. I am showing you my hand because ideally, I want you to consider the larger implications of all this.

That whole “Alternative Facts” statement was such a remarkable moment, especially when you consider that, essentially, Kellyanne Conway and Chuck Todd were talking about photographs, specifically the ones taken from the Mall on inauguration day. She was saying that she could look at a photograph of something indisputable and dispute it, based solely on her political standing. The amplified effort into blurring fact and fiction through ones chosen media absorption is really alarming.

William Livingston, 2014 © Jayson Bimber

Feinstein: These are obviously political, but where are you personally in all of this? What's driving you to investigate, critique, and pull apart wealth and consumer culture?

Bimber: I investigate and critique wealth because I believe the greatest issue facing contemporary society is income inequality. I think that a lot of problems stem from the 1% owning so much incredible wealth and power that they are able to manipulate the lower 90%. If you look at something like global warming, deniers place their beliefs around a series of well funded lies created by a few purchased scientists. This same scenario can be seen across multiple industries, Big Pharma, the Housing Industry, etc. and is a system of our capitalist structure. Trickle down economics makes it worse and worse. Recently, as congress debates tax code, the Institute for Policy Studies found corporations that get big tax cuts actually will slash jobs in order to boost CEO salary.

I grew up in a middle class family in rural Pennsylvania. These lifestyles are pretty far away from my own personal experience. I am not Tina Barney, exploring her family and friend’s wealth, I am an outsider. I come to this work from a point of pretty extreme ambivalence, desire and a denial of that desire.

I like things. It would be nice to have fancy camping equipment, a nice outfitted stereo, an art collection. It’s the stuff I dream about when I allow myself the luxury of buying a Powerball ticket. However, I also grew up with punk rock, a subculture that revels in a rejection of capitalism and consumer culture. It’s pretty engrained in me at this point to question lifestyles of opulence and my own desires of want.

Rusticators, 2015. © Jayson Bimber

Brittany Livingstone, 2014 © Jayson Bimber

Dinner and Gossip, 2016. © Jayson Bimber

Feinstein: I see a ton of art-historical references here, from still life to portraiture, to tableaux -- can you tell me a bit about their significance to you and this work?

Bimber: My practice relies a lot on appropriation and not just the imagery used in its construction. I often pull from different texts as a way of creating a jumping off point, whether it be a joke or an article discussing wealth in someway. Along side this, as you mentioned, I pull from art history for compositional references or concepts I want to create work around. I find inspiration in historical artistic traditions and seek to critique those traditions. For instance, my portrait Brittany Livingston (above) was created in direct reference to Ingres’ painting Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière. I like Ingres, he realistically rendered clothing but idealized faces and bodies and painted wealthy patrons. I like pulling those concepts into conversation with my work while winking back at the original.

I also pull from art history as a way to elevate the conversation around the work. Creating humorous, satirical images with “bad Photoshop” I think it could be easy to write off these images. I think adding in the art historical references allows me to say, “no this is on purpose” in a sense.

I question authorship by using all of these sources. I think it’s a way of creating a conversation from quotations. Not unlike how an academic would cite sources in a paper. I’m not just taking compositional decisions from art history, I will put another images in mine or even take elements from my contemporary’s photographs and collage them into my own.

Getaway, 2014 © Jayson Bimber

Feinstein: In your statement, you talk about this work as being a critique of financial wealth, but I think it goes much deeper than that.

Bimber: As I stated earlier this work deals a lot with my own feelings of ambivalence towards wealth and I don’t think it is a coincidence I started this it not long after I began my current position an elite private academic institution. There is a lot of wealth at that school, from donors, to it’s dining hall, to the appearance of the campus, and it manifests itself in the privilege not all but a few of the student body enjoy. When I started teaching, it was kind of a shock. This work definitely come from a place of trying to investigate and understand the systems in place for the awarding of financial advantages and disadvantages to people at birth. Like trying to grasp the smugness one can have when they were born on third base.

I believe pretty strongly that Photography has a rich tradition of reportage and exploiting of the poor behind a facade of advancement of cause, while doing so for artistic personal gain. It very often seems disingenuous to me. So, I want to look at the opposite side of the spectrum and address wealth while using material and stereotype to address affluence.

We also live at a time when there is an obscene amount of money funneling into contemporary art for a select few. The wealthy use contemporary art as investment opportunities and to diversify their portfolios. So, I am also trying to address that culture in some of this work, using art to critique the practice of buying and selling art.

Exposition, 2015. © Jayson Bimber

Stereo, 2014. © Jayson Bimber

Feinstein: Most, if not all of the people in your images are white.

Bimber: I am keenly aware the series features a lot of white bodies, this is mostly to do with me being uncomfortable as a white male satirizing how people of color chose to display wealth. To speak about that experience as an outsider in a satirical way could easily be seen as incredibly insensitive or worse. However, as it grows I am now becoming uneasy with the amount of whiteness in the series. It’s really tricky and something currently I am spending a lot of time considering and trying to navigate.

Feinstein: How are you sourcing the images that you use to make this work? What's your process look like?

Bimber: My process mostly involves combining scanned images from magazines with pictures I find using Google. I have created images in the series entirely from scanned photographs, and I have created some entirely from Internet sources, but most typically it is a combination. I really like the way resolutions from different sources play off each other in the final print. I own a lot of magazines and save a ton of printed material and will look through these searching for certain gestures, clothing, or facial features.

Nimrod, 2014. © Jayson Bimber

Feinstein: I understand you've worked as a professional retoucher?

Bimber: I have worked as a retoucher professionally in the past and still do occasionally on a freelance basis. In my past work, even before I worked professionally, an analysis of the photographic practice of retouching played an important role, most specifically in regards to the body. I have been interested in the fabrication of photographs for a long time and very much enjoy critiquing photographic manipulation using its own procedural tools. I think there is plenty to discuss when you think about Photoshop as something more than just a compositing or enhancement tool and instead analyze how it changes our understanding of photographs.

Feinstein: These are mostly found images. How do your own photographs play into this?

Bimber: Sometimes I will need a hand in the correct gesture or a small element and its easiest to just photograph it myself. I photograph a lot of small architectural elements and furniture in other people’s houses and public spaces to use. Other times I will create an entire background, like in the images Cherry Hill or Gala. Cherry Hill I created as I walked through Central Park one day, pretty spontaneously; Gala I made in the bathroom of the contemporary wing at the Art Institute of Chicago and went there with the purpose of making that photograph.

An Evening at St. Regis, 2014. © Jayson Bimber

Feinstein: Most of what you've shared with me was made in 2014-2016. Are you still making work for this series?

Bimber: Yes. I currently have 3 separate pieces I’m working on simultaneously. I have begun thinking about the scope of the project, it’s at around 25 right now and I thought 100 seemed like a nice number. Who knows if it will be that much, I may get bored and run out of things to say long before that, but as of right now I think I have so much source material to pull ideas from that I don’t see an end.

Feinstein: Where does it go from here?

The work hasn’t yet been shown together, as a whole series, and that is something I am trying to do. I think they work best as printed objects and at scale (which varies piece to piece). That viewing gives the opportunity to observe how the pieces fall apart under scrutiny and let the viewer in on the joke. So that is something else I am working towards.