Beach, 2015 © Charlie Kitchen

In the introductory essay to Charlotte Cotton’s 2015 anthology Photography is Magic, she argues that photography’s current “moment” has broken free from analog nostalgia in a move to use photographic tools – digital or otherwise – with a newfound sense of freedom. This “freedom,” embraced by photographers who came up under the spectre of digital-ness often rests on open and continuous experimentation. San Antonio-based photographer Charlie Kitchen’s – Standard View (2015) and Recent Work (2016) builds on this idea through a series of in-camera collages that weigh trial, errors, and tactility over highfalutin conceptualism. “After shooting my thesis with a 4x5 camera,” says Kitchen, “photography began to unravel itself and I began to dig deeper into the medium, rather than contemplating what I could shoot to convey any sort of feeling or concept.” While skeptics might see this as avoiding conceptual responsibility, it’s a practice that has allowed Kitchen, like many photographers today, to unearth photography’s many tools for expanding visual possibility.

Penrose, 2015. © Charlie Kitchen

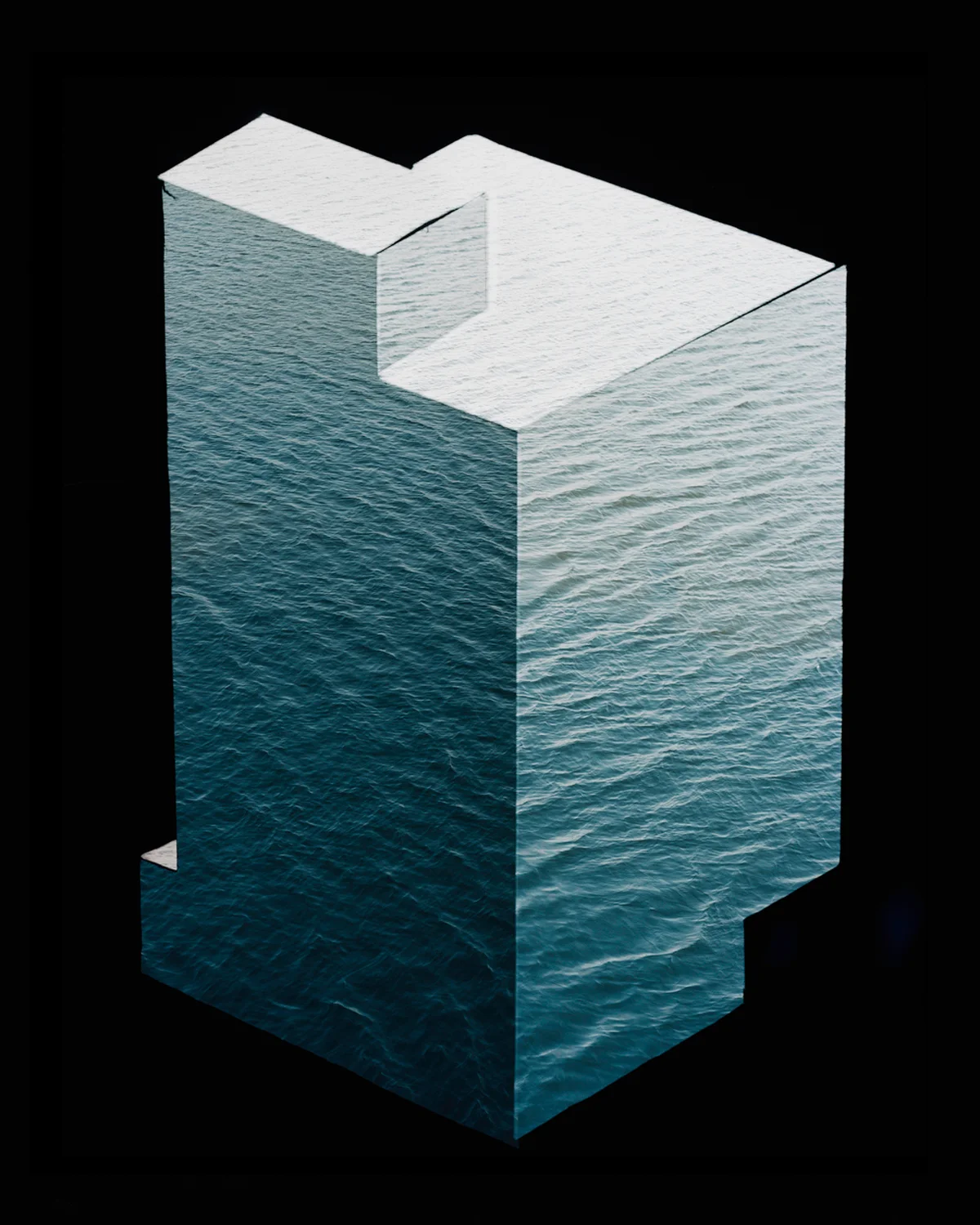

Aquahedron, 2015 © Charlie Kitchen

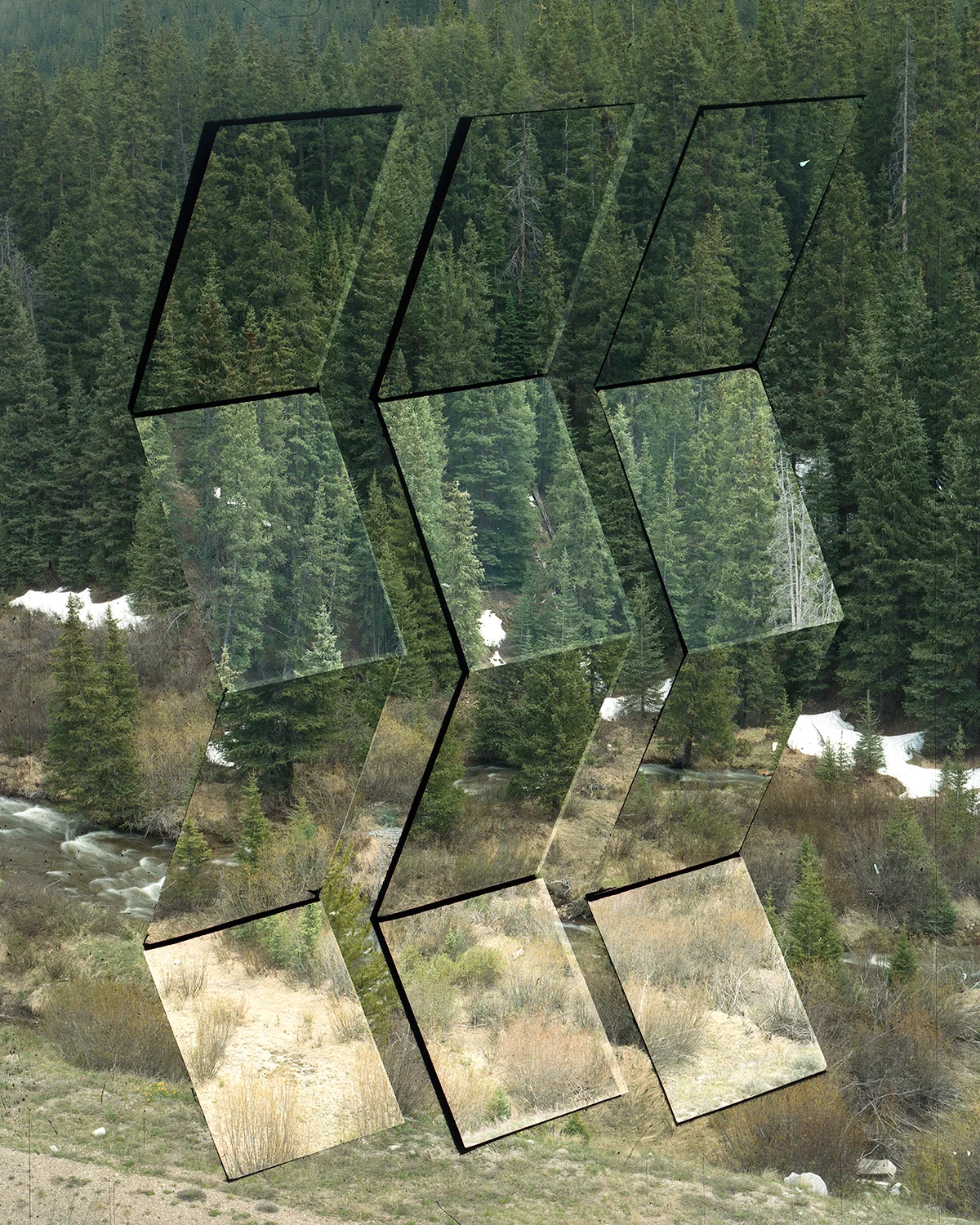

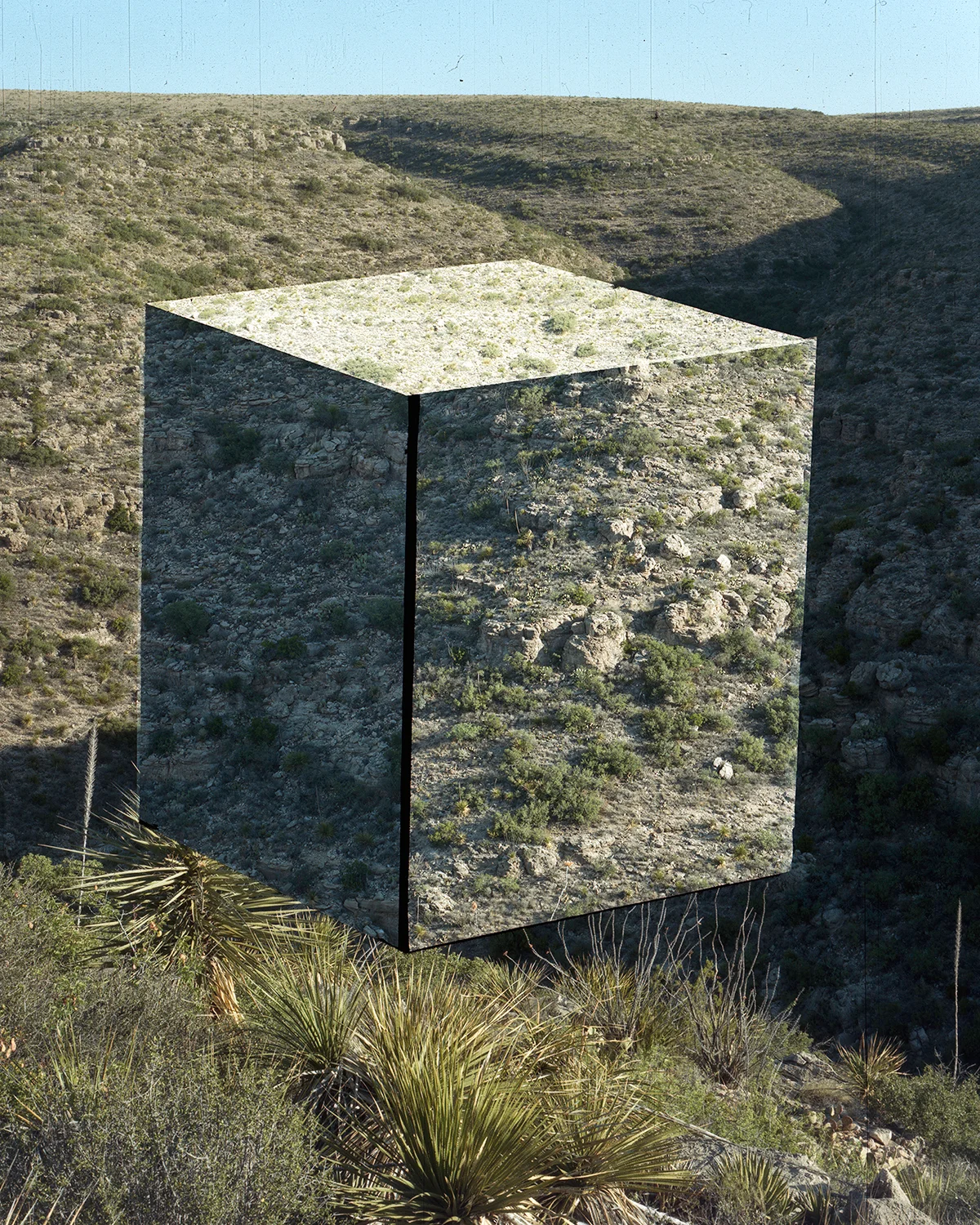

Kitchen’s 2015 series Standard View was a first step in what he describes as an “investigation into flatness.” At first glance, it appears to be a series of standard pieces of natural elements - water, sky, foliage- superimposed onto black backgrounds to bridge studio and landscape practice. Penrose, 2015, for example, initially looks like a random black and white swatch of sky was shoddily pasted into a triangular optical illusion. But the flaws in its edges are actually manual cuts, and while digital plays a role in balancing color and removing dust from the negative, the images are shot entirely in camera using masks cut from a black paper to selectively expose each piece of film. For most of 2015, Kitchen continued making images like these, but quickly branched out to create inverted masks with clear material, pulling these fragments from their voids and into more complex, colorful landscapes. Forest, 2015, which depicts a transparent cube floating among trees, creates a psychedelic void, not unlike scenes from John McTiernan's 1987 film Predator.

Forest, 2015. © Charlie Kitchen

Analog Matte #008, 2016 © Charlie Kitchen

Kitchen expanded his process during a recent road trip to Colorado in June, 2016, with multi-layered landscapes that combine and conflate the viewers sense of space and depth. For these images, Kitchen continued to use masks and 3-D printed templates to block out sections of exposed film in-camera, combining his penchant for experimentation with landscape photography’s exploratory roots, namely Ansel Adams and many of the early US Geological Survey photographers. Images from this series, uniquely printed on large scale fabric, are currently on view at San Antonio's Southwest School of Art.

Analog Matte # 012 (San Isabel), 2016. © Charlie Kitchen

Roso Frisco, 2016 © Charlie Kitchen

Kitchen is not the first to dabble in large format in-camera collage. Dan Boardman, for example, has employed a similar practice over the past few year with painstakingly constructed pictures that showcase photography’s psychological and emotional eccentricities. Additionally, Hannah Whitaker’s work, specifically her recent series Verbs, appears digitally collaged and also relies on masking sections of film and making multiple exposures on a single sheet. Kitchen acknowledges Boardman and Whitaker’s influence and sees his process as working in tandem to theirs. “I create work through the same process,” he says, “although I focus on different aspects of photographic imagery. Standard View experiments with this idea of the flatness of the photographic image. I like to think of what I’m doing as creating a seemingly three-dimensional image through a medium that is fundamentally two-dimensional….” His outlook on photography in general is one that allows for various iterations of trial, error, and the failures that occasionally come along with them. “It is incredibly liberating,” he says, “ to be able to make work for the sole purpose of seeing what will happen."

Analog Matte #005 (Rattlesnake Canyon), 2016 © Charlie Kitchen

Analog Matte #018 (moraine), 2016 © Charlie Kitchen

Bio: Charlie Kitchen received his Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography from Texas State University, San Marcos. He now resides and works in San Antonio, TX as the Building and Events Coordinator at Artpace.

Text by Jon Feinstein