© Ben Alper

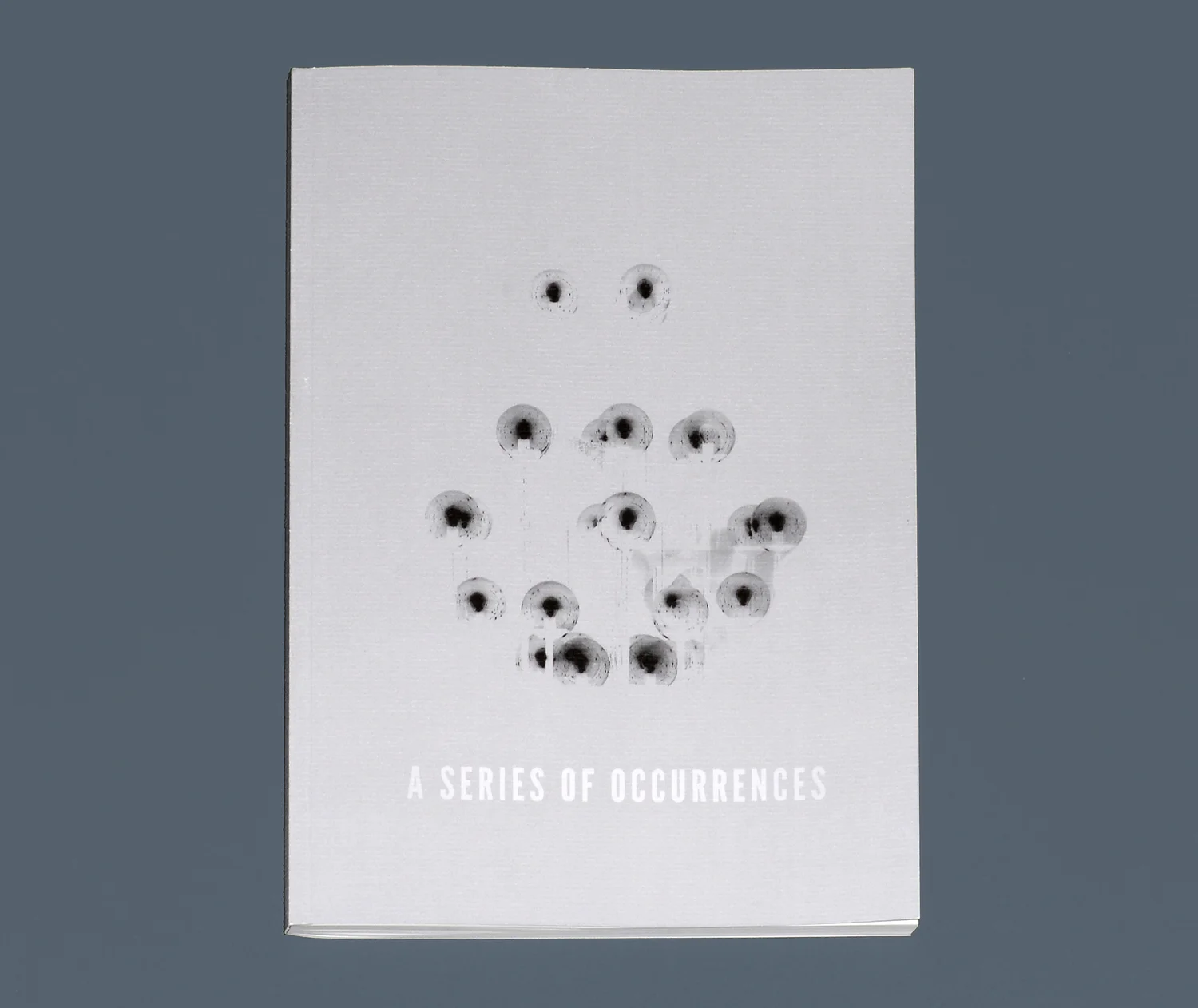

Photographing the everyday can be as trite as saying "A photograph is worth 1,000 words." In its worst form, the claim to "see" what others don't," or "elevate the ordinary," amounts to little more than plain, boring pictures. But when it works, it can be transcendent. Ben Alper has a unique way of transforming the banal into funny, poetic and utterly unsettling pictures. Whether it's digitally disassembling found photos or wandering through condemned houses and uncharted landscapes armed with only a really bright flash, Alper helps viewers see the world as a fragmented, noir-ish crime scene waiting to happen. His recent photobook (which you, dear readers, should buy, especially, this limited edition), A Series of Occurrences, published by his imprint Flat Space Books, follows this sense of discomfort, subjecting the landscape to intense visual scrutiny while pairing and ultimately forcing relationships between seemingly unrelated images. Think Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel's 1970's Evidence collection, but shot by a single photographer. We spoke with Ben to learn more.

Jon Feinstein In your statement, you reference the "anonymous American landscape" -- Would you say there’s something particularly “American” about these images?

Ben Alper I don't know if I'd say the images are particularly American. So many feel like they could have been made anywhere. But in a way, I think it could be argued that that does make them in some way quintessentially American. So much of the contemporary American landscape is oppressively homogenous, but I also tend to make photographs in a way that generally denies a certain amount of context. For me though, there are so many more narrative possibilities when anonymity and ambiguity are pushed to the forefront and ideas of "Americanness" are suppressed to some degree. Or, that was the case with this book at least.

JF: Where were these pictures actually made?

BA: These pictures were made in various places in the American East - from Massachusetts, to New York, to North Carolina, to Georgia, to Tennessee.

© Ben Alper

© Ben Alper

JF: I know so many photographers hate this question, but tell me a bit about your process

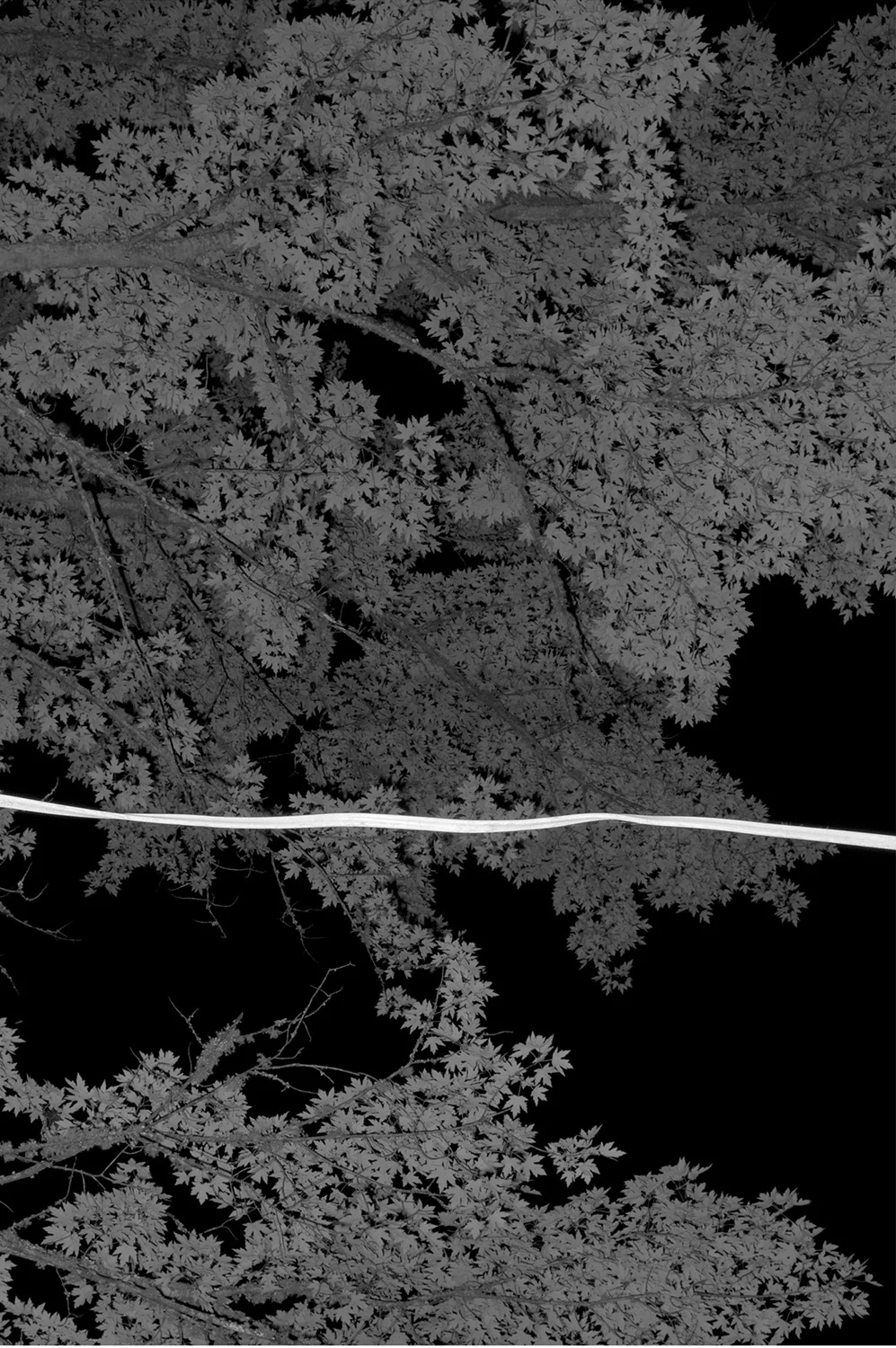

BA: All of these images were made on happenstance walks or drives in various locations. Often times I set out to make pictures, but would just wander aimlessly on foot for a few hours with a camera and a massive flash. Other times I would set out in a car in a similar fashion, looking for pictures, but never knowing where I'd find them or what exactly I was looking for. Sometimes I'd roam around neighborhoods; other times strip malls or parking lots; other times abandoned houses. It really depended on the day.

JF: Does shooting entirely in Black and White impact the narrative?

BA: The decision to make this work in black & white was less about narrative in a linear or noir sense and more a choice based on a move toward abstraction, or a move away from reality. The starkness of the contrast, the bluntness (and often crudeness) of the light, and the limited tonal range creates a dispassionate gaze. Color can be too emotionally-suggestive. I wanted the work to feel emotionally distant, or psychologically isolating in some way. The decision to utilize black and white was more in service of that. More about a kind of restraint than a kind of expressiveness.

© Ben Alper

© Ben Alper

JF: You imply an author-less, even scientific description of horror, but these images still have a very pointed gaze. Where is "Ben Alper" in all of this?

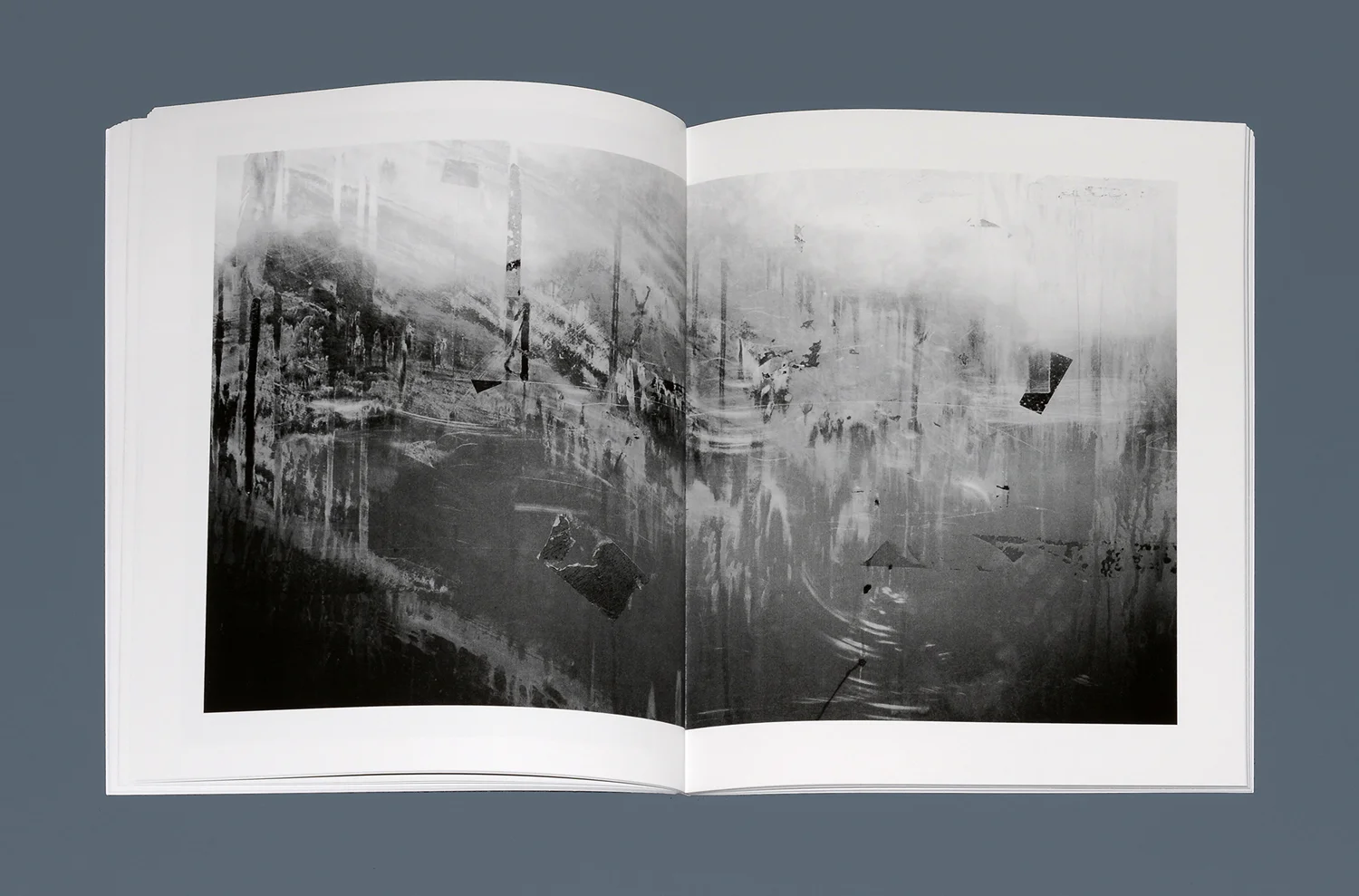

BA: This is an interesting question. I have definitely appropriated both a visual language, and to some degree a technique, consistent with more descriptive or evidentiary forms of image-making. However, where I have entered the work the most forcefully is by preventing the images from actually behaving as evidence. So many have been fragmented to such a degree that meaning breaks down, or should I say, opens up to multiplicity and uncertainty. I've used a coded visual language associated with evidence-gathering, but stripped away that part of the methodology through framing, cropping and spatial disorientation.

© Ben Alper

JF: Where does the title come from?

BA: The title comes from a quote in an essay called Terrain Vague, written by the Catalan architect and historian Ignasi de Sola Morales. It's a piece of writing that's been hugely influential for me. It has a bit of a double meaning. From a very literal perspective, it speaks to the fact that these images were photographed discretely, a part from another, that they were "a series of occurrences". But I also like that the word occurrence means both "an incident or event" and "the fact of something existing or being found". This for me speaks both to the photograph itself as an event and to the photograph as an evidentiary or indexical object. The work in this book is admittedly influenced by various forms of vernacular photography, in particular by the blunt scrutiny of crime scene photography in particular.

JF: You used Terrain Vague as the title for an earlier project as well. How does A Series of Occurrences speak to that previous work - specifically your interest in collecting and manipulating found photos?

BA: Like I mentioned above, the work in this book is certainly influenced by my relationship to vernacular photography. I was thinking about and looking at a lot of crime scene photography when I was putting this book together. I had been buying lots of 4 x 5 negatives on eBay from various dealers of these amazing crime scene negatives. They were so haunting, rarely graphic, often just beautifully cryptic. I was entranced by them. I also studied them from a formal and technical standpoint to understand exactly what the photographers were trying to achieve, from an evidence gathering perspective. My strategy was often to mimic the aesthetic or the visual language, but to undermine the conceptual strategy.

© Ben Alper

JF: As long as I've known you, you've also been drawn to the "everyday," "overlooked," "ephemera" etc. What draws you to this?

BA: For me it's always been about an attempt to shift perception, both in myself and in my viewer. And It's one the things that photography does so well, if approached with care and vision. I think fundamentally, it's been my way of dealing with habit, routine, repetition and tedium. Photography has proven to be an escape from the banalities of daily life, precisely by attempting to face them with clarity and directness. I know that sounds contradictory, but this medium for me has become more a coping mechanism or a philosophical exercise than anything else. Yes, I view it as an art. But that is almost secondary to a more essential purpose that it serves.

© Ben Alper

© Ben Alper

© Ben Alper

JF: What would be the soundtrack to this work?

BA: Brian Eno - "In Dark Trees" and “The Big Ship”(From Another Green World)

Trying to articulate the connection between the images in A Series of Occurrences and these two sequential Brian Eno songs from Another Green World is challenging, in part because there’s such a strong component in each that seems to exist beyond language. That being said, this music makes me feel I how I want the photographs to feel - unsettled but excited, a little apprehensive, energized, and left with a sensation of experiencing something both familiar and simultaneously new.

© Ben Alper

Bio: Ben Alper is an artist based in Durham, North Carolina. He received a BFA in photography from the Massachusetts College of Art & Design in Boston and an MFA in Studio Art from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Alper’s work has been shown widely, including group exhibitions at the NADA Art Fair in Miami, Higher Pictures in New York, Le Dictateur Gallery in Milan, Italy, Schneider Gallery in Chicago and S1 Gallery in Portland. Additionally, his work has been published in Time Magazine, The British Journal of Photography, Conveyor Magazine, The California Sunday Magazine SPOT Magazine and Dear, Dave. Ben has also published two books under his imprint Flat Space Books – Adrift and A Series of Occurrences. He is also the co-founder and co-facilitator of A New Nothing, an online project space dedicated to hosting visual conversations between artists.

Author: Jon Feinstein