Photo Editor Gabriel Sanchez and Photographer Steven Eichner at their Long Beach, NY studio, 2019

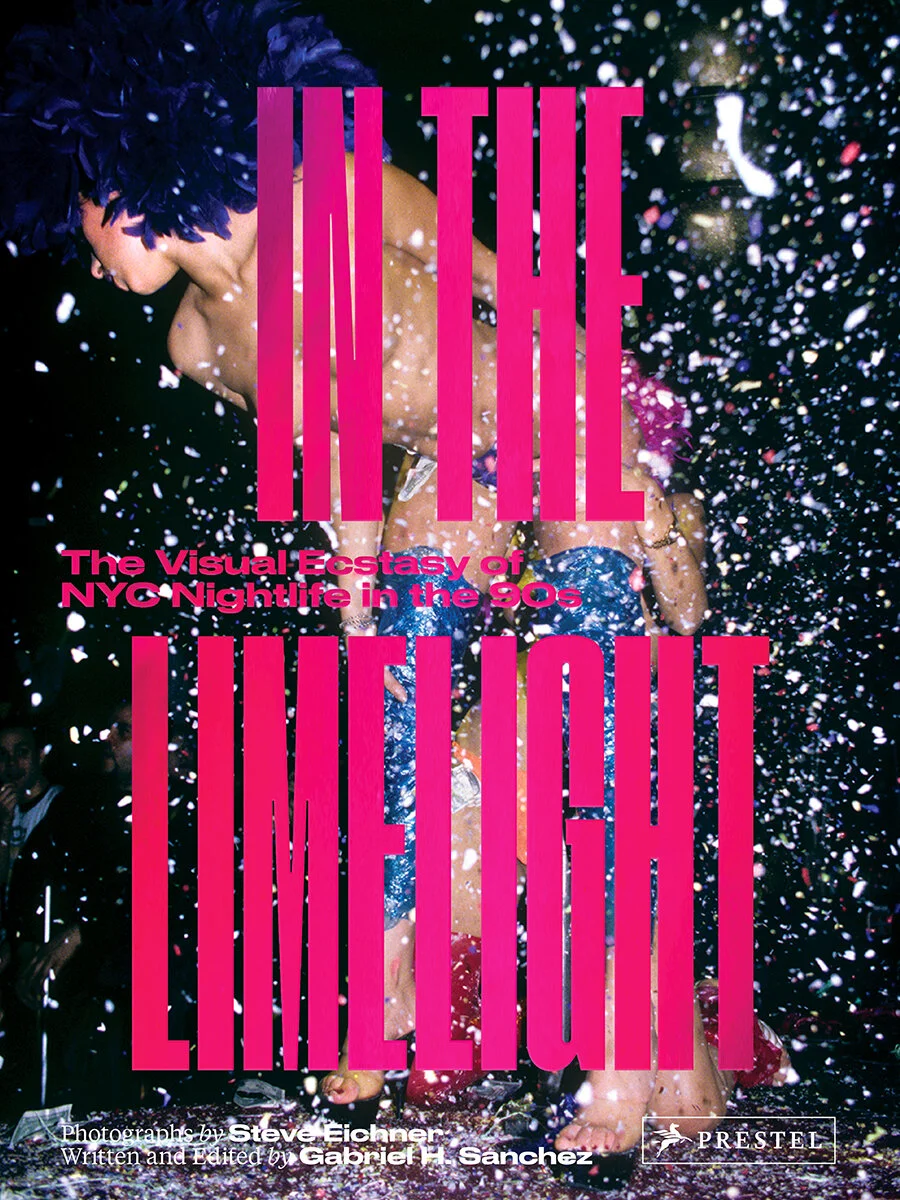

Humble speaks with Gabriel Sanchez about his inspiring career and the story behind editing legendary 1990s NYC nightlife photographer Steve Eichner's new book In The Limelight

Gabriel Sanchez is one of today’s most inspiring photo editors. After writing for Aperture and Artforum ( that’s is EARLY work!) he carved a following and niche developing thousands of stories as Buzzfeed’s Features photo editor. Sanchez recently took a job at the New York Times assigning a range of photo essays and stories, working closely with photographers he'd previously admired from afar.

Amidst a career change and the pandemic, Sanchez edited In the Limelight: The Visual Ecstasy of NYC Nightlife in the 90s, a new photobook published by Prestel that celebrates the work of Steve Eichner, one of few photographers with insider access to photograph the wild and crazy 90s club scene in NYC. Oh, and he also became a dad.

I spoke with Sanchez to learn more about the project, his advice for up and coming photographers, and what it’s like having hands in so many reaches of photography.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Gabriel Sanchez

Club USA, 1993 © 2020 Steve Eichner

Jon Feinstein: Congrats on In The Limelight. I want to get into that in a minute, but first, I'd like to talk a bit about your career. I've been following your writing from your days at Aperture and Artforum through your work at Buzzfeed where you built a massive following covering such a wide range of photography. What prompted your move to the New York Times?

Gabriel Sanchez: First — I really can’t tell you how much I appreciate you following my writing. During my time at BuzzFeed, what kept me inspired and motivated were those readers who continued to follow my photo essays and who would really bare it all in the comments to say how much they were affected by a particular image or that they finally felt visible because of a specific body of work we featured.

It wasn’t always like that of course — there was a bit of a curve in my early days there in gaining reader’s trust and getting the word out that I was someone who was taking photography seriously at BuzzFeed. This was a pre-Trump dossier era of the company, when many thought we were only about listicles and cat memes. It was probably very confusing for some readers to see the work of Manray or Joel Meyerowitz next to that. For others, I think it felt validating — and those were the people who I wrote my photo essays.

What prompted my move to the New York Times was an opportunity to apply my vision for photography in creating new and original art by working closely with photographers, not necessarily as a journalist or a critic, but as a co-producer and an advocate.

Gabriel Sanchez and the BuzzFeed News art dept. at the Society of Publication Designers awards ceremony, 2019

Feinstein: You've been at The New York Times for over a month now. How is your role different from what you were doing at Buzzfeed? What are you focusing on right now?

Sanchez: To your last question, our photo-coverage at BuzzFeed was incredibly wide-ranging and no two weeks ever looked the same. One week might have been a museum preview or an artist profile and the next would be reportage on wildfires or widespread protest.

The New York Times has allowed me to focus my vision on developing and assigning art to stories that only the Times has the breadth to take on. In my short time since beginning, I’ve worked closely and commissioned art from photographers that I’ve only been able to admire from afar — talent like Akasha Rabut, Andrea Morales, Ryan Lowry — on stories covering everything the racial inequality, the #Metoo movement, and even something wild coming up soon with rapper Action Bronson.

Sanchez’ table card at the Palms Springs Photo Festival portfolio review, 2017

Feinstein: I'm sure you get asked this question ridiculously often and I risk an eyeroll, but I know it will help our readers so I'm going to ask anyway. You've written about thousands of photographers, and have likely looked at more than 10X that in your career. What draws you to writing about someone's work?

Sanchez: This is a really great question and something I’m always happy to talk about. It might be different for all editors, but for me I’ve always taken note of sincerity and work ethic. There are some people who are just naturally gifted photographers, but the vast majority of photographers I’ve interviewed or hired have had to work very hard to get where they’re at today. Rarely will a photographer step out into the world, shoot 15 iconic images and close the door on the project. Good photography takes time and commitment. Those are traits that I’ve always been attracted to when looking through portfolios.

Feinstein: Any advice for how photographers should approach content editors?

Sanchez: I always tell people that kindness goes a very long way! Many editors have their work emails listed openly on the internet (BuzzFeed editors have their emails available on their author pages fyi!) — otherwise, Instagram, Twitter, and Linkedin are great ways to make a connection. It doesn’t hurt to reach out with a kind hello and a good picture to share.

Feinstein: Onto the book - I read in Vanity Fair that you first connected with Steve Eichner after seeing his name as a repeated byline for 90s club photography. When you reached out, did you have a book in mind? How did the relationship and book development transpire from there?

Sanchez: When I first came across Steve’s work, I was working on building a photo essay for BuzzFeed on New York City’s club scene in the 1990s. It was an evergreen idea I floated to my editors that was really only based on my own personal love for the art, music, and culture of the era. It was also an idea that I knew would be difficult to illustrate.

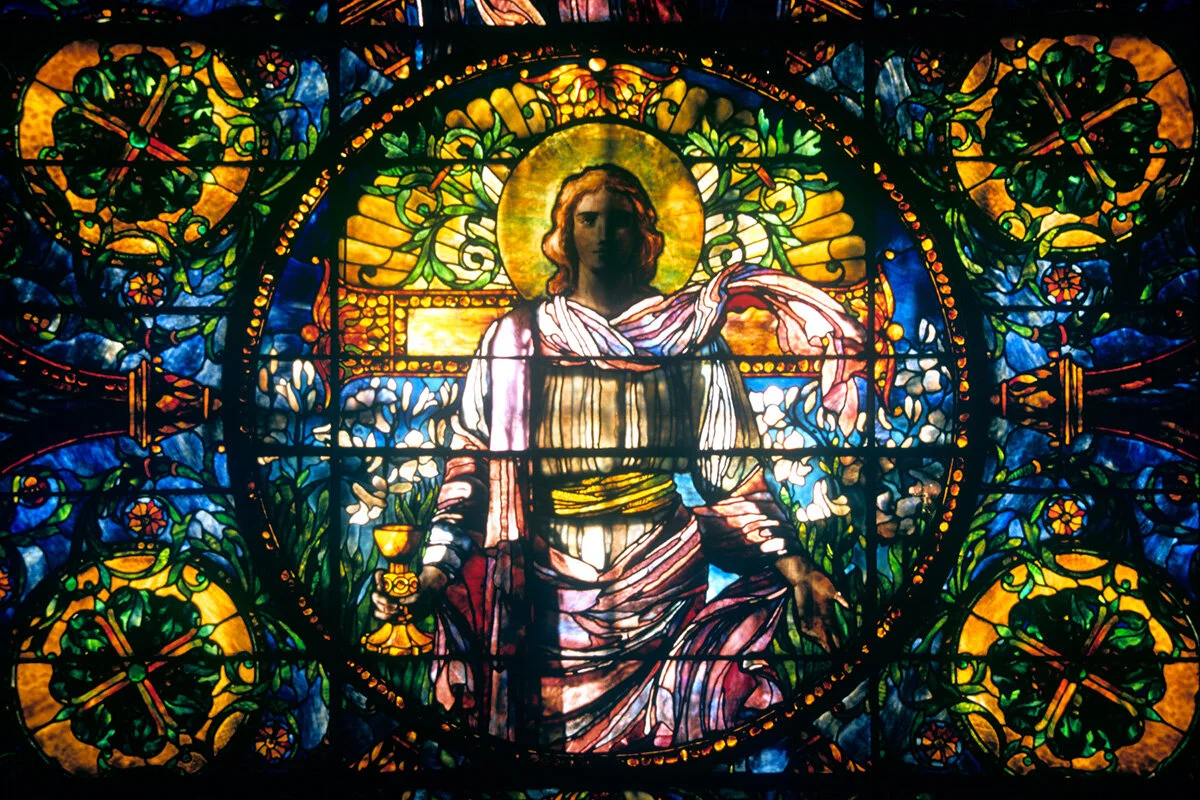

Simply put, the pictures of club kids and club goers in iconic NYC venues like the Limelight, Tunnel, and Palladium just don’t exist on a professional level. When I eventually discovered Steve’s work, I realized exactly why this was — club owner Peter Gatien kept a pretty tight lid on photographers in his club and had only allowed professional access to somebody he designated as his “house photographer.” That person was Steve.

Limelight, 1999. © Steve Eichner

Club USA, 1993 © 2020 Steve Eichner

Feinstein: How did the relationship and book development transpire from there?

Sanchez: I interviewed Steve for my story and we really hit it off. We connected on our mutual love of photography, music tastes, and even skateboarding — you might have caught us shredding the concrete bowl in Long Beach at some point! Steve shared with me his interest in compiling his best images into a book and I promised him that I would make it happen. It took many years to fulfil that promise, but we’re both remarkably grateful to see it become a reality.

Feinstein: Do you recall the first Eichner photo that caught your eye? What drew you to it?

Sanchez: The picture that really caught my eye was a 1993 portrait of Michael Alig, Richie Rich, Nina Hagen, Sophia Lamar and Genetalia, posing together at Tunnel. The shot is so raw and spontaneous — it’s one of those images that pulls you in and has you asking questions that really have no answers. Their expressions are sinister and their fashions otherworldly. For me, the question that I couldn’t let go of (and I’m grateful I found an answer to) was who on earth had this type of unadulterated access to these people?

Michael Alig, Richie Rich, Nina Hagen, Sophia Lamar, and Genetalia backstage after Hagen's New Year's Eve performance at the Tunnel, 1993. © Steve Eichner

Half pipe at the very back of the Tunnel, circa 1993 © 2020 Steve Eichner

Feinstein: Beyond this being great work and story, was there anything about it that you connected with on a more personal level?

Sanchez: Part of what Steve and I connected on was our mutual love for the era — images and tales of New York City in the 1990s were what inspired me to move to New York. Steve and I often joke that every generation of starry-eyed kids who move to NYC always tries to live up to a bygone era of the city. In the 1990s, people would often move to the Village to live something close to what Bob Dylan might have once experienced, whereas part of what inspired me to attend graduate school in New York was to get a first-hand taste of what I had read in Disco Bloodbath.

The Tunnel, 1994 © 2020 Steve Eichner

Club goers dressed as The Fabulous Wonder Twins at the Roxy, circa 1993 © 2020 Steve Eichner

Feinstein: On one level, I like to think about this work for where it sits in the history of subculture and nightlife photography... A spot between Studio 54 photographers like Meryl Meisler and Bill Yates, Glen E. Friedman's punk photos... and the weird early-social media era in the early 2000s of photographers like The Cobra Snake and LastNightsParty.... Do you look at this work within that line of photo history or is it its own thing?

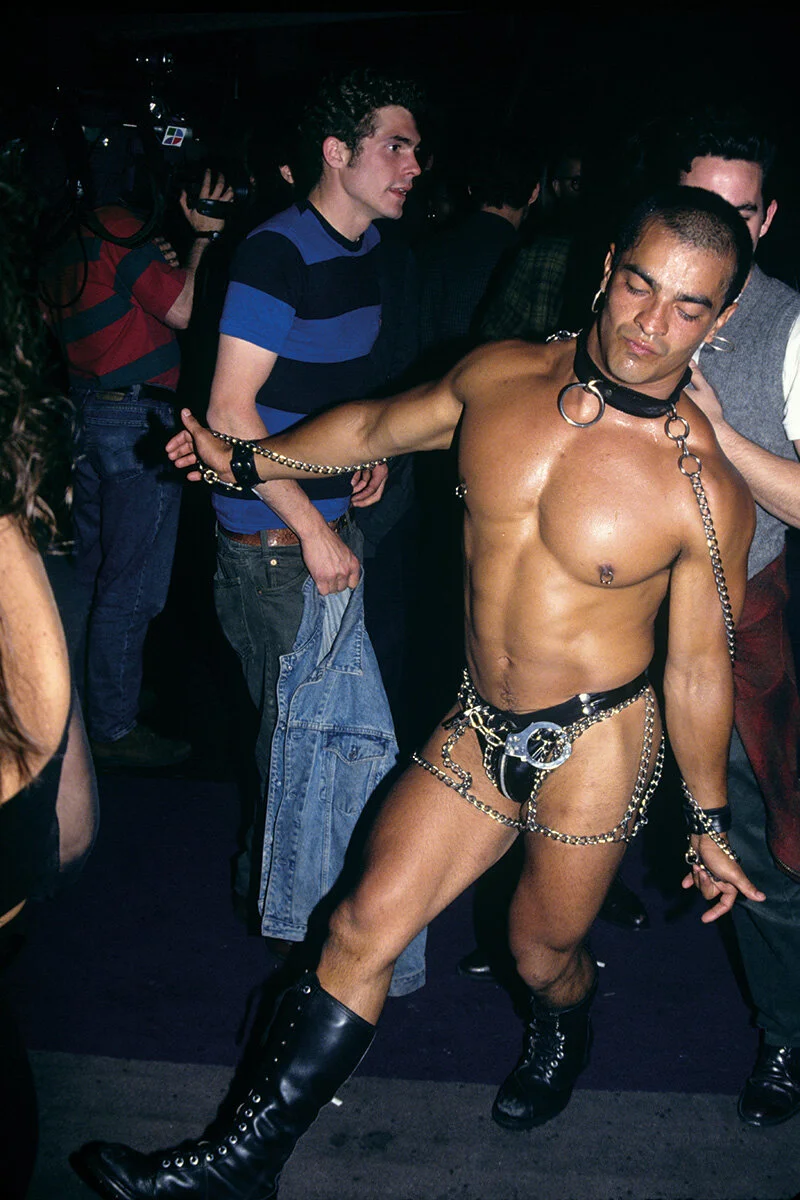

Sanchez: Steve’s pictures in many ways do offer a unique stepping stone between Meryl Meisler and something like LastNightsParty (which by the way, I haven’t thought of in some time — thanks for the rush of nostalgia!) But what I find most unique about Steve’s work was that it was never intended to function as a cultural record of any kind.

Steve was hired by Gatien to photograph celebrity guests for promotion in newspaper and tabloid spots, yet some of the most fascinating pictures in the book were the pictures that Steve shot to finish his roll or to test his lighting. These were pictures that were never intended to be sold or even shown, pictures he made in-between his money makers for his own pleasure. There were times when I was dusting off crates of slide film during the book’s production that had not seen the light of day in decades, it felt something akin to discovering Vivian Mayer in a chicago yard sale.

Shampoo Room at the Limelight, 1995 © 2020 Steve Eichner

The Palladium, 1995 © 2020 Steve Eichner

Feinstein: The release of this book comes at an interesting time - photos of people, partying freely. A sense of liberation, connectedness, community, and freedom in this work - a word you use to set up your introductory essay. Beyond the clear and important contrasts you make to today's influencer culture and social media, do you see a conversation or parallel between the notions of freedom in these photographs and today's political climate/ division (not overlooking the clear divisions, police brutality in NYC and other issues that existed then)?

Sanchez: Absolutely. It’s important to remember that most of today’s political divisions existed then as well and in some cases to a larger, more troubling degree. The era was overshadowed by the police beating Rodney King, the trail of the Central Park 5, the murder of Matthew Shepard, and the impeachment of Bill Clinton, to name only a few of the moments when severe cultural and political lines were defined across the nation. Still, the freedom witnessed in Steve’s pictures existed despite these differences, which I find tremendously unique to the era.

It was as if these spaces simply did not exist in the same plane of existence as the rest of the world. The baggage had to be left at the door — that was the rule and you were rewarded with the night of your life if you obliged. Tribalism existed, of course. Which is why you begin to take note of a spectrum of subcultures in Steve’s pictures — but you’ll never see any form of animosity between different factions. Today we see some of the individuals in these pictures and wonder how they could have possibly ended up in the same room together.

To be honest, I believe it’s something that would be tremendously difficult to exist in today’s social/political climate, which was a driving reason for me to work towards publishing this body of work. In some ways, it’s aspirational.