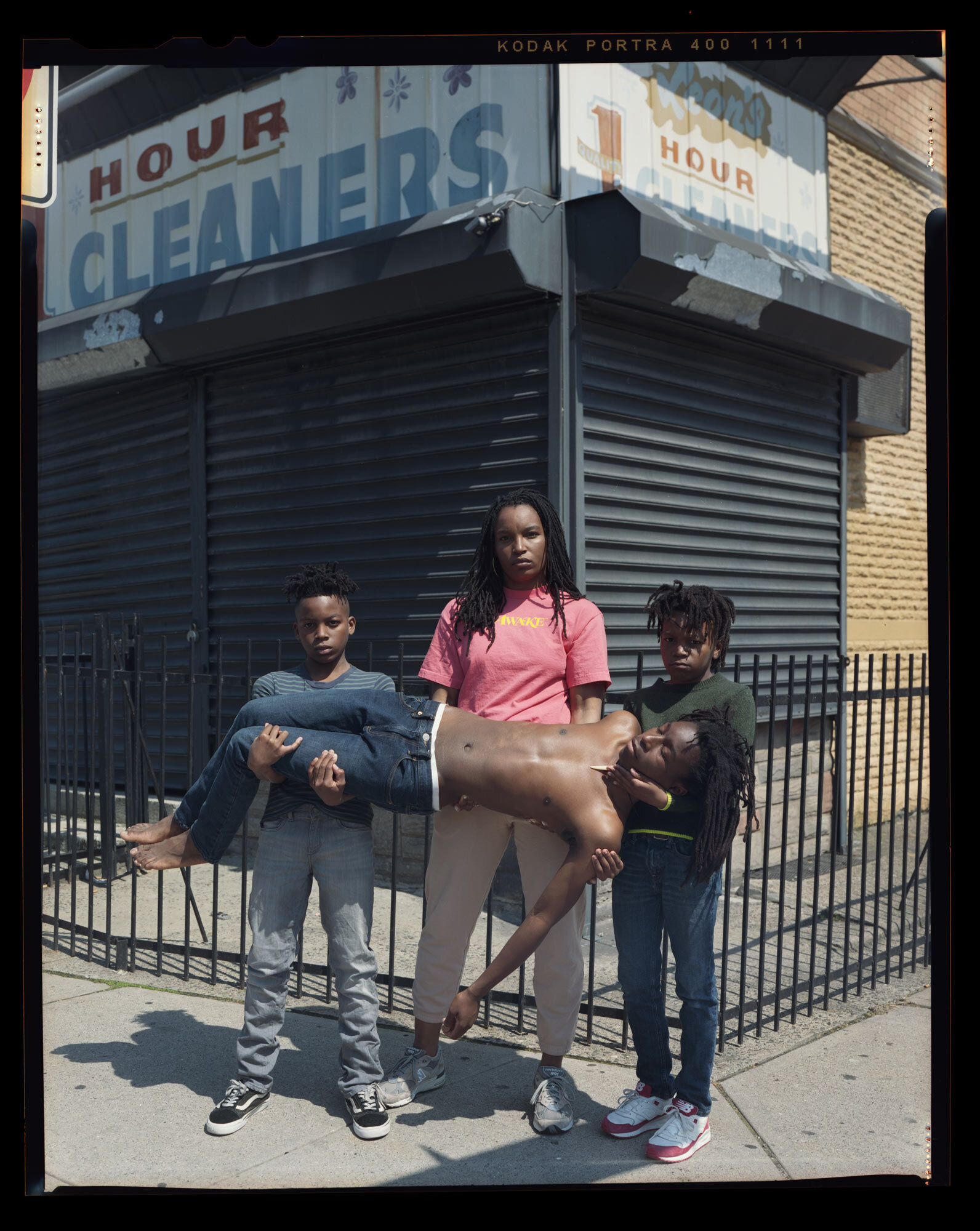

Untitled #33, Jersey City, NJ © Jon Henry

Jon Henry’s ongoing series, Stranger Fruit, uses the classical pietà – Michelangelo’s sculpture of Mary cradling Jesus – to illustrate the enduring pain of Black mothers who have lost their sons to police brutality.

New York City-based photographer Jon Henry stages portraits with various women around the United States cradling their sons on street corners, in parking lots, in front of government buildings; everyday spaces that symbolize the horrific commonplace-ness of racist, systemic murder. While Michelangelo’s Pieta casts Mary looking down at Jesus, many of the women in Henry’s portraits lock eyes with the lens, and us as viewers, returning our gaze with sadness, strength, and, depending on who’s looking, condemnation.

Henry paces these portraits with images of the women in bedrooms and other quiet, empty spaces, a signal of contemplating loss and endurance. “Lost in the furor of media coverage, lawsuits, and protests,” Henry writes, “is the plight of the mother. Who, regardless of the legal outcome, must carry on without her child.”

While the women in Henry’s photos have not actually lost their sons, these slow, reflective portrait sessions, made with a 4x5 camera represent living with a constant fear of police violence.

Henry occasionally intersperses text from a few of the mothers he photographs, often organized into poetic stanzas. For Henry, these passages speak to the experience of mothers across the country:

I feel sad,

sad that mothers actually

have to go through this…

My son was able to get up

and put back on his clothes

Others not so much.

They are still mentally frozen

in that position, that sadness,

that brokenness. I feel guilty

to be relieved that it’s just a

picture because for others

it’s a reality.

I feel scared, I feel next. I feel like Tyler could be the

next hashtag.”

Henry started the series in 2014 in response to the police murders of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice, and continues as they never seem to end. He recently won the Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture for this series which will be on display at The Griffin Museum through October 23rd and has several images in Photographic Center Northwest’s latest exhibition Examining The American Dream in Seattle, Washington, up through December 10, 2020.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Jon Henry

Untitled #55. Little Rock, AR. © Jon Henry

Jon Feinstein: Religious iconography is a major component of this work - not just Madonna and Child but also the influence of Dr. David Driskill's painting "Behold Thy Son." Can you tell me a bit about this?

Jon Henry: I used to work in a church, the church in Untitled #10, Flushing, NY (the first image in the series) so I was always glued to religious iconography, stained glass windows, and renaissance painting. It all had an impact on me, when thinking how I wanted the images to look and feel. Dr Driskell, along with Renee Cox and many other artists influenced the work. His influence was powerful because of his piece “Behold Thy Son” which he painted one year after the murder of Emmett Till. He was so impacted by that story that he had to create this pieta in response to Emmett’s murder. So, there were parallels in how he was affected by Till’s murder and me affected by Sean Bell’s murder.

Untitled #10. Flushing, NY. © Jon Henry

Feinstein: This project seems to mark a shift in how you photograph. Your past series felt more reportage-heavy while this seems to mark a visual/ aesthetic and conceptual shift, thick with art history, typology, and so much more.

Henry: I had been interested in more conceptual work for some time. While photographing sports on field, I was bored as the images were no different than the person next to me, so I began to look for different ways to represent athletes. This project accelerated that thinking and put a number of themes together.

Feinstein: Why is large-format/ the 4x5 camera important to this series?

Henry: I knew early on that I needed to photograph this series on large format. I wasn't satisfied with digital and I knew that to heighten the importance of the single image, that the pace needed to slow down. I needed to look closer. The 4x5 made it all possible, working just one image at a time. It raised the bar, I had to be more meticulous than with previous works, but I knew it was the right decision.

Untitled #19 Magnificent Mile, IL. © Jon Henry

Untitled #36. North-Minneapolis, MN. © Jon Henry

Feinstein: Can you talk about your decision to include text?

Henry: Once the image is final, I email the family a copy of the image. I send the mothers a copy of the image and a short questionnaire of about 5 or 6 questions, asking about their thoughts going into the project, describing the action of holding their son(s), and how they approach the topic with their son(s) if they have yet. The texts remain anonymous and they are laid out throughout the piece. Having the text from the mothers helps drive home the fact that this is a real issue, these are real families that worry about this issue daily. Their voice is as strong as any image in the series.

Feinstein: You made these photos all over the country. Is there a significance to the specific cities and locations?

Henry: The locations are important to give the viewer context as to where these atrocities have happened. They are random areas across the country, so big cities, rural areas, wherever I try to make images with as much variety in the backdrop as possible.

Untitled #11 Buffalo, NY. © Jon Henry

Feinstein: Your images are all untitled/ without names, and as viewers, we don't know who these women and their sons are, yet they don't feel anonymous (aside from their location) - they feel just as personally heartbreaking. Can you talk a bit about this?

Henry: It speaks to the fact that these tragedies could happen to any one of them. They have not lost their sons, but they understand the reality that this could happen, as it continues to happen routinely across this country. Their names aren't important, but speaking to the larger issue at hand is.

Untitled #02. Co-Op-City, NY. © Jon Henry

Feinstein: What is your relationship to the women and sons in these photos?

Henry: The families are friends of friends, some are my family, some folks reach out independently, but

we stay in contact and I send them info on the project as it moves forward.

Feinstein: What does your collaboration process look like when making these photos? How are they responding to the process/ to seeing their images?

Henry: I send them a detailed email before we meet that outlines what we will do and what the expectations are. They have seen previous images and know the pose and I figure it out when I arrive to their location. Everyone has been amazing, they know the importance of the work and are super helpful and open when we are together. I guess to know how they respond when first seeing the final image is another question for the questionnaire.

Untitled-13. Groveland-Park, IL, 2016. © Jon Henry

Feinstein: Can you talk about your decision to photograph the young men in these photos without their shirts?

Henry: I’m just thinking of vulnerability and protection. Aesthetically it helps the work flow together, but my focus is on the fragility of the body and how it can be harmed.

Feinstein: Has making this work and getting it out into the world helped you process the continued racist murders of Black men (and women) by law enforcement?

Henry: No, not at all. It’s still stressful and overwhelming that in 2020, in the middle of a global pandemic, we are still having these conversations. It’s a bit like enduring the trauma all over again with every new story.

Feinstein: Are you still making this work? What marks its continuation/ endpoint?

Henry: Yes, this project is ongoing. I’m working on the last few locations now. I’m just trying to photograph in St Louis, Utah, and Nebraska and I think the work will be complete.