The Wall, 2018. © Griselda San Martin

“I Hear America Singing,” curated by Ashley Lumb at the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts in Amman, Jordan presents a wide and inclusive picture of contemporary American photography.

For 19th Century poet Walt Whitman, America was the sum of its people – an ambitious symbol of collective participation and responsibility. His 1860 poem “I Hear America Singing” celebrated democracy in its most ideal form - something the country has, for many, continuously fallen short. Taking its title from Whitman's poem, Ashley Lumb’s exhibition – the first exhibition of American photography to take place in Amman, Jordan – features the work of 16 contemporary American photographers showing the many experiences of America and American identity.

Lumb uses three themes: Landscape, Portraiture and American History to frame the exhibition.This ranges from Lucas Foglia's poetic images of rural America to Millee Tibbs folded abstractions that distort and push against the hyper-masculinity of early American Landscape photography. Highlights (but really, every image in the show eloquently articulates the puzzle of American identity) also include Wendell White's series "Schools for the Colored," which presents locations in Northeastern states that once functioned as segregated schools, digitally edited to "screen out" surrounding area, isolating them from white society.

I spoke with Lumb to learn more about this exciting and ambitious exhibition.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Ashley Lumb

Rocks and EaEagles, 2017-2019 © Matthew Brandt. Daguerreotype made from American Silver Eagle coins and glass.

Feinstein: To start - congrats on getting this show together! From your recent Instagram post, it sounds like it was a daunting endeavor, curating, producing, etc internationally. How do you feel about everything now that it's up? And what do you think was the biggest challenge curating from afar?

Ashley Lumb: Thank you! I’m very happy with how everything turned out. It all went to plan apart from one framing mishap, but there was a language barrier I couldn’t quite overcome. I don’t speak Arabic and couldn’t communicate with the framer in Jordan so we relied on a translator and obviously some of the nuances got lost in translation. A lot can go wrong in an exhibition and so I’m thankful there were no significant disasters.

Freedom from Want © Hank Willis Thomas in collaboration with Emily Shur and Eric Gottesman. From the 2018 series “Four Freedoms”

Feinstein: What do you think was the biggest challenge curating from afar?

Lumb: The logistics of international shows can be mind boggling. I’ve done a fair few and there are always so many moving parts. The main problem was getting the works to the museum because I couldn’t post them to Jordan, it’s basically impossible to get things into the country through their customs. The best option was to personally courier it over on a flight. Luckily I was able to pack the entire show - all 65 works by 16 photographers - into two large boxes. Additionally, organizing insurance in a country that doesn’t really insure art proved a bit of a quandry. In the end that wasn’t possible, so we just crossed our fingers and hoped for the best. Thankfully most of the photos were only exhibition prints.

Feinstein: Wow. I imagine COVID made things additionally challenging?

Lumb: As with most of the arts world, the outbreak of COVID put us in a rather tight spot. One of the featured artists was going to fly all the work to Jordan. It would have been his first time there too, but then the situation flared up in the country right before he was due to fly and the show had to be postponed. I dropped everything and drove up to San Francisco from LA, packed the whole exhibition into my temporary car, which had clocked-up almost 300,000 miles on it, and teetered back to LA along coastal Highway 1 just praying my car would make the trip. I didn’t mind though. I got to camp overnight by myself with all the artworks in Big Sur. And I should add that I physically hauled the art to Jordan in a whirlwind 4 day trip! Talk about adventures in independent curating!

Future City, IL. 2008 © Wendell White from the series “Schools for the Colored.”

Feinstein: It’s a broad question, I know, but how would you define “contemporary American photography?” Beyond geography, what does it mean to be an “American Photographer”?

Lumb: I thought of American photography here as photos simply taken in America. The photos could be taken by citizens, visiting artists or immigrants, and they didn’t have to only depict American citizens. In the documentary images from Michael Lundgren and Lucas Foglia, you see citizens from all walks of life, including Dutch tourists and cowboys from South America. The exhibition was fully supported by a grant from the American Embassy in Amman, and because of that my remit was to bring American culture to Jordan.

For the show I wanted to feature as diverse a selection of American photographers as possible. I’m a firm believer in the importance of inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility. My last exhibition in America was about Australian photography and it also included some incredible work by immigrant artists and often depicting marginalized communities. As someone who has lived in 10 countries and been an immigrant themselves, I think it’s important to give visibility to anyone living in the country.

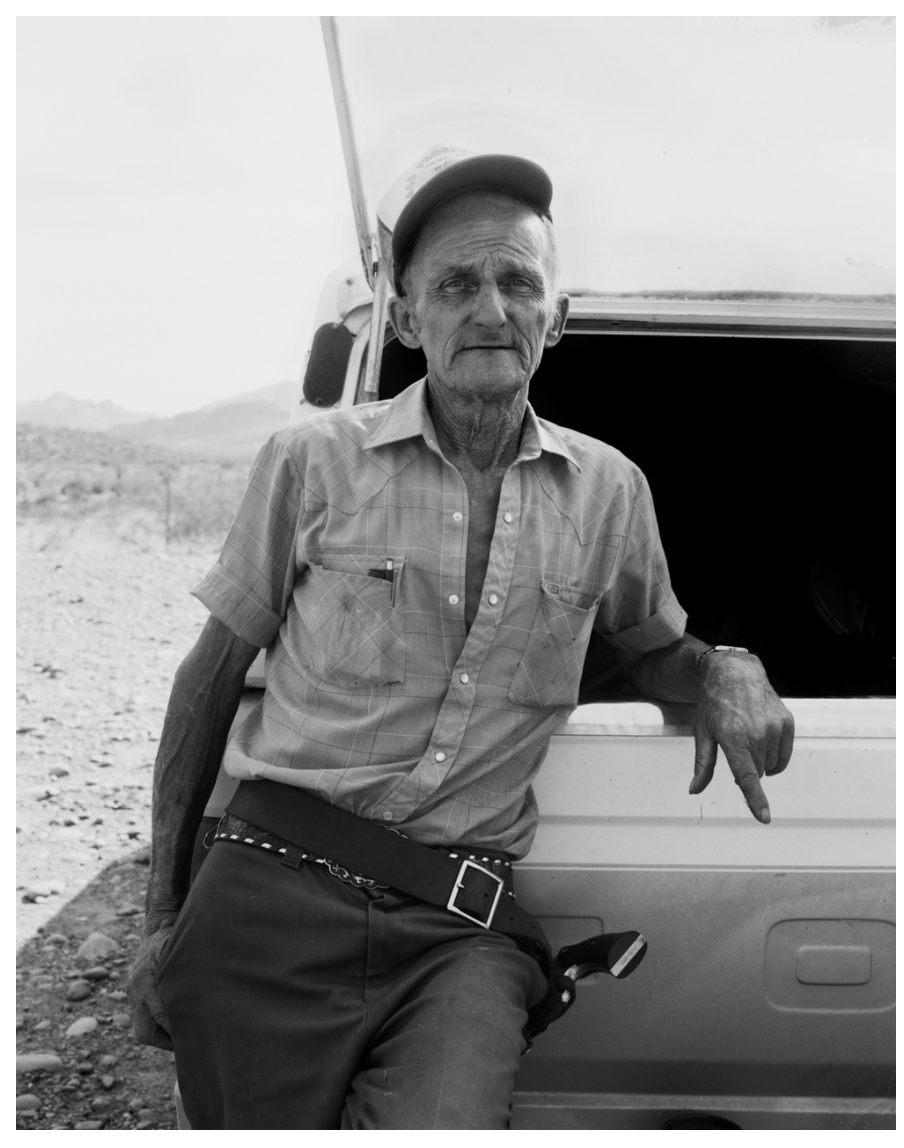

Don Hurd by the Salt River, 1998 © Michael Lundgren

Feinstein: What sparked the idea for this exhibition?

Lumb: I was living in Jordan and working at The American Center of Oriental Research and was looking for my next curatorial project, so I turned to the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, which is, admittedly, the only art museum in the country. In the 18 months I’d lived there, the National Gallery had hosted several region-specific exhibitions, one on Australian and one on African art. But I realized there hadn’t been an American exhibition for over 20 years.

It also felt appropriate because there are a lot of Americans in Amman. The U.S. Embassy there is the largest in the Middle East and there are quite a lot of American citizens in the country working for NGOs. Plus, I had to fully fund the exhibition and the Embassy was able to provide very generous support. That was invaluable during the pandemic as financial support became increasingly difficult to find.

© Griselda San Martin - The Wall, 2018

Feinstein: How did you go about selecting the artists and work?

Lumb: I held a brief post working at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson recently, but I’d spent most of my adult life outside of the US, so I didn’t really have a solid awareness of contemporary American photographers. It was really helpful to have a grant, giving me more time and freedom to spend on research. Often with my independent exhibitions, they’re a bit rushed because I’m doing them with little to no budget in addition to other work. In this case I was able to do an entire month of research when I left Jordan in December 2019, returning to the states and settling in Los Angeles.

To help me discover new and exciting artists, I researched as many museum exhibitions in America as I could, read online publications, and reached out to people I knew in the arts. I found a few excellent photographers while acting as a portfolio reviewer for Medium Festival in San Diego, and had actually worked with Griselda San Martin in London a few years back.

Sundown number five and fourteen, 2018. © Xaviera Simmons

Feinstein: I love Griselda’s work! The title of the exhibition is an homage to Walt Whitman - can you discuss how this relates to the work in the exhibition and your curatorial process?

Lumb: Walt Whitman’s poetry is seen as reflecting a quintessential American experience, embodying ideals that Americans tend to strongly identify with. In “I Hear America Singing” he acknowledges the vital role that every individual plays in the harmony of the nation, and I felt that the sentiment of his work echoed the country’s diversity and I wanted to highlight and celebrate that. I intended for the exhibition to reflect a broader sense of “Americanness” rather than a narrow and typically Anglo-Saxon view. So the exhibition features photographers from a range of backgrounds, and their practice represents the experience of Asian Americans, Native Americans, Black Americans, multiracial citizens...Put together it depicts the melting pot of ethnicities and identities in the U.S.

There is something of a dichotomy in Whitman though. Because, no matter how sincere his ideals, the reality in America at that time was one of slavery and racial oppression, with civil war breaking for example just months after “I Hear America Singing” was published. So, there’s Whitman’s dream of equality that we should keep fighting to realize, and the difficult realities we should continue to illuminate. I feel there’s a balance of work here that broadens representations, and work that visually deconstructs a monocultural myth of American history and white supremicist ideology. Either way, for me the title remains hopeful, rich with the possibility of national unity.

Desert Housing Block, Las Vegas, NV, 2009. © Alex Maclean from the series “Arid Lands.”

Feinstein: Did your selection and research confirm, expand, or shift any ideas you had about American photography and identity?

Lumb: The U.S. is so multifaceted it was hard to make so few selections, and the show inadvertently became skewed towards the American West, likely because I wanted to draw some comparisons between the landscapes of America and Jordan. Alex Maclean’s series Arid Lands, David Benjamin Sherry’s American Monuments, and Millee Tibbs work Mountains + Valleys both depict desert scenes that could easily be Jordan. I would have loved to include some urban grit in there too, but physically there just wasn’t the room.

In doing the research I was surprised at how many white male photographers there were, because I had just lived in Australia for a few years and the photography scene seemed to be skewed towards female practitioners. I was heartened to see just how many great artists there were in America though. Australia’s art scene is quite small, so you tend to see the same names. Now that I’m back in America for good, I’m excited to familiarize myself with all the new work that’s being produced. I’m keen to focus on American artists more, though mostly for the logistics - international shipping can be a nightmare!

Grand Plateau, Grand Staircase - Escalante National Mounument, Utah, 2017 © David Benjamin Sherry. Form the series “American Monuments”

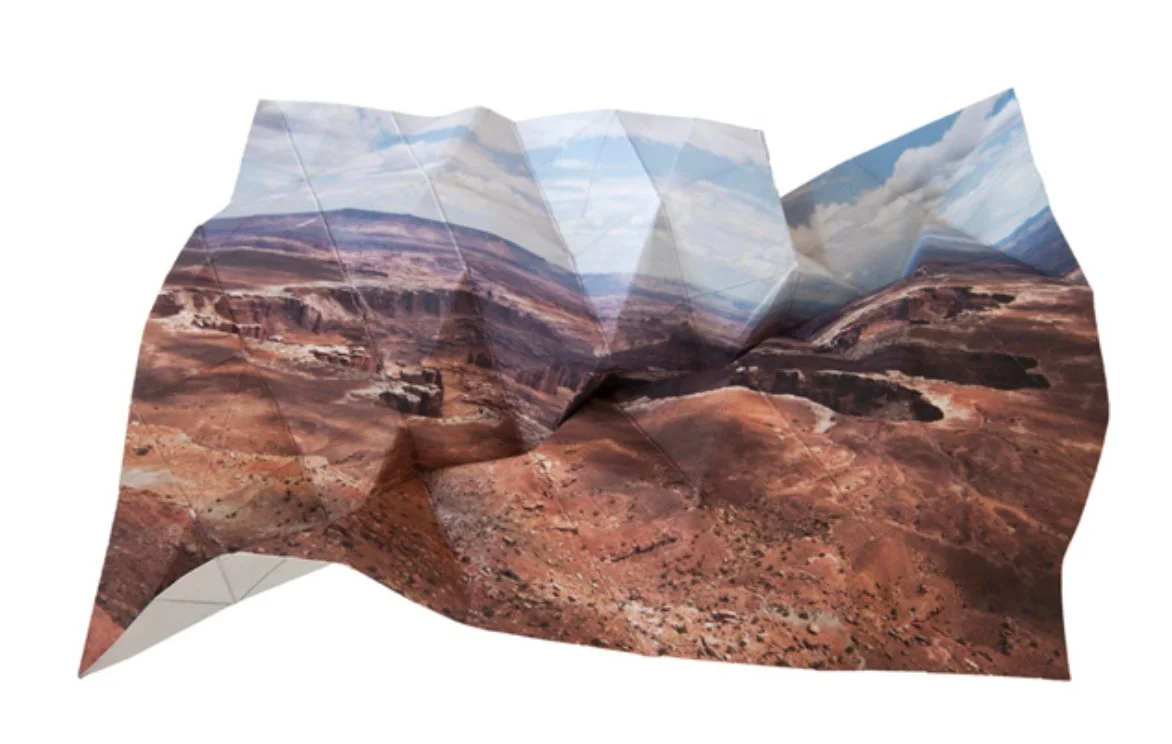

Canyonlands #1 © Milee Tibbs. from the series “Mountains and Valleys,” 2013

Feinstein: One thing I’ve been thinking about with this show –as it’s being exhibited in Jordan – is how it both centers and others American Photography. We are so used to seeing shows in the United States that showcase work outside the US with a kind of exoticized curatorial lens. And now you, as an American curator, have organized the first show of American photography being exhibited in Amman. This kind of flip feels powerful. What do you make of this?

Lumb: Well, although I’m technically American, I do feel more like a foreigner, because I’ve lived abroad most of my adult life and have a different perspective than a solely US-based curator would. It was all done with fresh eyes. I wasn’t aware of half the artists in the show before I started developing it.

In all the countries I’ve lived in, I can’t recall any exhibitions that were America-specific in the sense that they tried to tell a story about America. You tend to see shows curated around Western art movements or individual artists. The idea of America has kind of saturated the popular consciousness, thanks to films, TV, and the media, so that there doesn’t seem to be a need for a focussed show...except for in this one rare place in Jordan that hadn’t really shown much American art. Though I’m sure the logistics of shipping and funding play a large part in that.

Yellowstone #4 © Milee Tibbs. from the series “Mountains and Valleys,” 2013

Feinstein: In your statement, you mention how the work in the show pushes against male hegemony in the United States. With the show exhibiting in Jordan, where progress on women’s and LGBTQ+ rights has a distance to climb, how do you anticipate that important piece of the narrative coming through?

Lumb: There are a few works in the show that push boundaries. For example, women in Jordan do have high ranking jobs in government, medicine, academia, and so on, but there are some jobs that only men can do, like being a waiter or Uber driver. So it was great to include a work by Lucas Foglia of a woman miner driving a haul truck in Nevada, a lovely image that chips away at the notion of prescribed gender roles.

© Lucas Foglia

Feinstein: With so many conceptual and aesthetic approaches to the work, how else do you see this coming through?

Lumb: While the issue of women’s rights isn’t explicitly addressed, a number of artists interrogate and shed light on a pervasive, masculinist ideology. Millee Tibbs and David Benjamin Sherry in particular focus on the American landscape and the way it’s been represented in American photography. Tibbs notes that her work explores a “gendered gaze that heroicizes the photographic possession of the landscape.”

Often, we perceive photographs of the natural world as innately objective. So she photographs iconic sites and then physically scores the prints using origami folds, to illustrate the idea that visual representations are transformed by the attitudes and beliefs of their historical moment.

And history has, by and large, been shaped by men. We see it in America’s project of Manifest Destiny and the impulsion to dominate and master the landscape for our own profit.

Sherry’s monochromatic American Monuments prints brilliantly compliment Tibbs’s series too, and his bright, saturated prints bring out...not only a kind of ostentatious beauty and grandeur in the landscape, but an ‘otherness’ too, hinting at a world that’s a bit different to the one we repeatedly depicted in photographs, as rugged and unyielding. I also thought that his images worked so well in this context, because they elucidate the striking similarity between the American and Jordanian landscape. His photo of the Grand Plateau in Utah could quite easily be a mountain in Wadi Rum.

Bears Earts, Bears Earts National Monument, 2018 © David Benjamin Sherry. From the series “American Monuments.”

And I Wander, 2019 © Wen-Hang Lin

Feinstein: Where are you personally in this/ why is this exhibition important to you now, historically and moving forward?

Lumb: I find curating group exhibitions hugely satisfying, because when I find previously myriad unknown connections between artists and artworks or traditions, and can link them together into a meaningful whole, I find myself in the exciting position of someone who’s discovered a secret of cosmic harmony.

My curatorial practice is also highly entwined with cultural diplomacy, and I use it as a means to export culture to other countries. I’ve lived in 10 countries now, and the desire to reflect on this lived experience has inspired me to curate 23 exhibitions across the U.S., U.K., Europe, Australia, and the Middle East. The majority of these shows have involved me bringing artists to countries where their work has never been exhibited before. I genuinely love the challenge that curating presents: creating rich cultural exchanges, promoting dialogues, and introducing diverse viewpoints.

Talking Tintypes © William Wilson

Feinstein: What do you hope or anticipate viewers will come away with?

Lumb: There is a wonderful bliss that goes hand in hand with the act of taking an idea and turning it into something the world can enjoy. For this exhibition, there is the main audience in Jordan, and there’s the international audience who will see the online version.

For visiting Jordanians, I hope they come away having learnt a bit more about American history and the issues we currently face. But I also think they’ll see how experimental photography can be, from a process point of view. The museum in Amman tends to display painting and sculpture more than photography. We take its ubiquity for granted here, but things like 19th century photographic processes can’t be carried out in Jordan because certain chemicals aren’t available.

For that reason I was pleased to include some modern daguerreotypes (Matthew Brandt), tintypes combined with AR (William Wilson), and Greg Stimac’s photogram of the golden spike, in addition to more contemporary experimental processes like collaging (Pamela Pecchio) and origami (Millee Tibbs). There are no photography schools in Jordan, so the majority of the photography shown tends to be self taught straight documentary or landscape images. I think it’s important for viewers (both the general public and artists) to understand where photography has been and where it’s going.

George Washington’s Teeth, 2021 Madison #1, 2021 Adams #1, 2017 Father (Jefferson), 2017 From the series “Founder” © Pamela Pecchio

Feinstein: Do you see this exhibition as being specifically “for” Jordanians?

Lumb: There is also an international audience that can see the show online. On my worldly travels I’ve had the pleasure of meeting a large number of arts colleagues and I’ve received some great feedback on this exhibition. A number feel that the show is an interesting look at where the medium is currently, specifically in regards its engagement with analogue processes to highlight broader cultural concerns, plus interest for the show to tour in Australia or America.

The curator’s job is to connect, so I feel I’m connecting these artists with the wider world, but also connecting them together in the show to tell a coherent story about America.