The critic and photo historian’s critical volume Latinx Photography in the United States: A Visual History fills in knowledge gaps and cuts news paths in researching, collecting, and exhibiting Latinx photography.

“The impetus for this book is derived from a basic fact: by and large, Latinx photographers are excluded from the documented record of the history of American photography.” From the prologue’s first sentence, readers are alerted to the content and critical framework of Elizabeth Ferrer’s extraordinary first full-length book. In its form, Latinx Photography in the United States, published by University of Washington Press resembles familiar titles such as Naomi Rosenblum’s A World History of Photography, but the scope is decidedly more focused.

Over ten exhaustively researched and written chapters, Ferrer identifies primary themes - representations of self, family, and community, geographical influences, archives, and the fight for social justice - that motivate Latinx artists, and form a narrative that parallels the canonical story of American photography from which they’ve been excluded. It’s an absorbing read, and a must for students and teachers of photography.

Elizabeth Ferrer graciously agreed to speak with me about the origins of this book, the joyful work of contacting the artists whose work is included in the book, and laying to rest any notion that Latinx photographers are simply absent from the medium’s complicated history.

Roula Seikaly in conversation with Elizabeth Ferrer

Louis Carlos Bernal. Dos Mujeres, Familia Lopez. Douglas, Arizona. 1979. © 2019 Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal

Roula Seikaly: Hi Elizabeth! It’s great to see you. I don't want to take up too much of your time today, so I’ll get to it. How did this project begin? What did the research reveal about Latinx photography over the last 180 years?

Elizabeth Ferrer: Thank you, Roula, for inviting me to chat. I want to back up a bit to say that prior to working on this book, I had been very involved in the world of Mexican photography. I was curating exhibitions, writing books and essays, and was traveling to Mexico City regularly. One project I was invited to do was relatively small, to edit an edition of Nueva Luz, the magazine published by the photo organization En Foco. They asked me to work on a special mentor issue dedicated to Mariana Yampolsky (1925-2002), who was born in the United States, but spent her entire career in Mexico where she became a leading photographer. That project led to a sustained relationship with En Foco. I began to meet photographers based much closer to home in New York and as much as I love Mexican photography, the organization became a catalyst for me to begin to explore the work of Latinx photographers. That was a while back; we didn’t use that term Latinx.

In 1994, I was invited by FotoFest, which organizes a major photo festival held every two years in Houston, to write an essay for a catalogue for what was the first major exhibition of Latino photography in the United States, American Voices. My work on this gave me even more opportunities to research Latinx photography, both historic and contemporary. Although that catalogue was never published, it motivated me to continue the research – I was finding a lot of remarkable work that had had little exposure. I became so invested in the work I was discovering that I eventually decided to work on my own book. So, in one sense the project started in the mid-1990s although it was in the last seven years or so that I was really working on the book.

I was intrigued by the possibility of finding historic figures and one of my sources was Peter Palmquist’s Pioneer Photographers of the Far West (Stanford University Press, 2000), which is a remarkable work of scholarship. It was in that book that I discovered a Latina working with daguerreotypes only a few years after photography was invented. I also discovered a few names through historical societies in Western states and with various threads of information, began to build a history. Of course, there is much more information on photographers from the Civil Rights era onward. For me, the book is like this beginning; there is a lot more work to be done. I hope the book is something I can build on, and also, that younger scholars will continue the research.

Nueva Luz Magazine. Vol-11. Issue-3 #1. Edited By Elizabeth Ferrer

Seikaly: That’s a great lead in for the next question. Do you treat this as a textbook, perhaps a title that educators in this country or anywhere photo history is taught can use?

Ferrer: It's an interesting question because for me a big question was how to construct the book. I didn't conceive of it as a textbook per se because I wanted as broad an audience as possible. But in the back of my mind, especially as the writing was coming to completion, my hope was that it would be read by students. One of the main points I make from the outset is that this history just didn't exist until the book was written.

There are no museum collections of Latinx photography, it's not taught in college courses, and it is excluded from survey exhibitions of American photography. Apart from a handful of exceptions, Latinx photographers have been largely invisible. So yes, I saw it very much as filling a gap, and my hope has been that it will be used in the classroom. And in fact, academics, especially those teaching Latinx art or cultural studies, have already reached out to me and told me that they are using it.

© Ricky Flores. Carlos and Boogie on the 6 Train. 1984

Seikaly: Oh, that's great! Can you talk a little about the structure of the book?

Ferrer: I spent a lot of time thinking about how to narrate multiple histories and how to structure an overall history. I discuss Puerto Rican photographers both in Puerto Rico and in the continental United States, primarily in the northeast; Chicanx photographers, traditionally centered in the Southwest; Cuban Americans, traditionally in Florida, as well as photographers descending from other regions of Latin America.

A big question is how to unite these groups – we share many elements but we also represent our own histories. I didn’t want to write separate narratives; this is Chicanx photographic history, this is Puerto Rican photographic history, etc. Although in many ways that would be instructive, it would also silo communities and I wanted to emphasize the qualities and challenges we share.

The text is roughly chronological, especially at the beginning, but then I began to move thematically, looking at how photographs express such realms as staging the self, family, geographies, and the archive. There are also chapters devoted to conceptual work and to photography in Puerto Rico. Overall I address civil rights, border issues, and cultural legacies, while also presenting a history of Latinx people working with the photographic medium.

Luis Medina, Gang Member, Sons of the Devil, 1978. Silver dye-bleach print. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago/ Art Resource, New York.

Seikaly: How did you settle on the 88 artists represented in the book? Did that number stem from the work that you did with FotoFest and En Foco very early on in this process?

Ferrer: Honestly, it grew pretty organically, based on the research I undertook. Many but not all of the photographers in the FotoFest exhibition are included. Working through Nueva Luz and the En Foco archives was a big part of my research. I'm Chicanx and from Los Angeles, so Chicanx art history is something I’m very familiar with. The research reflected in some major shows of Chicanx art over the last decade was also invaluable. I also looked at academic archives like Hunter College’s Center for Puerto Rican Studies, UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, and Wayne State University Labor Studies Center.

Early on I did research at UC Santa Barbara which contains a strong archive of the early Chicano period. Fortunately, a good amount of this material is now online; for example, photographs documenting the farmworkers movement in California has been extensively digitized. I spent a lot of late nights just looking through these archives and finding valuable information.

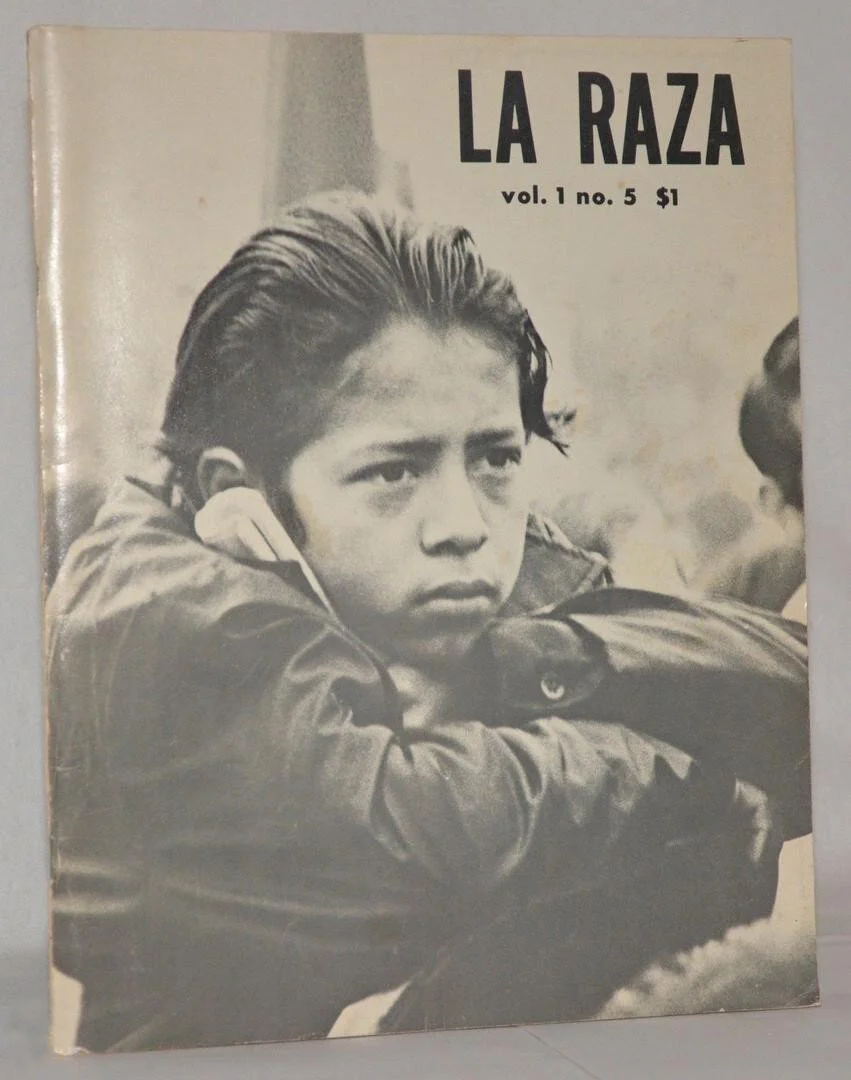

I wanted to give voice to photographers who never achieved renown, but were active early, in the civil rights era when this history really begins. Many Chicanx photographers documented Cesar Chavez and the farm workers’ movement but their names are hardly known. When you look at the visual history of that movement, it tends to be the big Magnum photographers or newspaper photographers from the LA Times and the like. They're not Latinx, but Latinx photographers were there. They worked for publications like La Raza and their participation needs to be better documented and exposed.

Justo A. Martí, A protest against Dictator Trujillo outside Rockefeller Center, 1948. Courtesy of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library & Archives, Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection, Hunter College, CUNY.

Seikaly: You mentioned the photographers who were working, but not attached to a major publication like the Los Angeles Times, or associated with an agency such as Magnum. Did those images go into family or smaller publication archives? Did you contact either the artists or their family, their heirs or their archive managers?

Ferrer: That was a huge part of it, just finding people, and it's really all of the above. I'll talk a bit about West Coast and then the East Coast. In the 1960s, a young generation of photographers in California were drawn to the Farmworkers’ Movement. This decade also saw the first substantial generation of Latinx people receiving higher education. And some of them go on to get MFAs and training in photography. Also in this decade, photography is becoming very popular, and is being broadly validated as an art form. Photo galleries and museums are beginning to open. All this is happening as civil rights protests are intensifying. So in California, young Latinx photographers are drawn to the United Farm Workers Movement, and they work essentially as volunteers; they're literally paid something like $5 a week and, I think, room and board.

One important archive is La Raza, which was a Los Angeles-based activist newspaper and later magazine that covered the civil rights movement and acted as an organizing platform for students and other Chicanx people. Another is the Farmworker Movement Documentary Project founded by LeRoy Chatfield. He kept a one-man DIY archive for many years before it was taken over by UC San Diego. It contains an immense amount of photographic work. It is not by photographers who saw themselves as artists. Rather, they were documenting in the heat of the moment and often disseminating their images on flyers and in local newspapers or student newspapers.

In New York, there were parallel political movements. Puerto Ricans that lived primarily in El Barrio in upper Manhattan were also pressing for city services, better schools and housing, and civil rights. This era was when the city was at its nadir; these poor neighborhoods were not getting services and landlords were torching decaying buildings to collect insurance money. A lot of this activism coalesced around the Young Lords, a political party and activist group. Their main photographer, Hiram Maristany, still lives in El Barrio and maintains his own archive.

And then there were the photographers involved early on with En Foco. En Foco maintains a large and again, little known photo collection. But finding photographers who worked independently has been more challenging; some of these photographers have now passed. For example, Rene Gelpi wasn’t really a political photographer, but an early street photographer in Brooklyn. I had heard of him and found a few images online but my attempts to find him always led to dead ends. And then strangely, I got an email from a photographer with whom I was acquainted, Jim Moore. He thought I might be interested in this photographer, Rene Gelpi… That came totally out of the blue!

La Raza Magazine Vol 1. circa 1969

Seikaly: Just out of the blue!

Ferrer: Exactly! He introduced me to Gelpi’s widow, who maintains the archive and allowed us to include his work in the book. And that's always sort of daunting, because when you're dealing with families, there can be so much emotion involved. I think Rene Gelpi's archive is well maintained, but not all families have the wherewithal to maintain the archives in the way that a university library would. I recently heard about one that was tossed in the trash – a real loss.

So, in some ways, yes, the research happened in a lot of ways. Some of it was traditional, but there was also detective work, and in some cases just repeatedly reaching out to people until we made contact.

Seikaly: Absolutely. I was thinking about what it would mean to do this work, all the detective work of tracking down the artists or their families, before internet ubiquity. That would have been so much more difficult. But, this project spans the pre- and rise of the internet. That’s a huge communication and information divide.

Ferrer: Very true. One example is Frieda Medin, who is based in Puerto Rico. She no longer photographs but made some important experimental work in the 1970s and ‘80s. I found her through a fellow curator who gave me the email address of a friend of hers. I was eventually able to secure her work for the book through phone calls and texts. It turns out she doesn't use email or the internet. So yes, the work can be arduous, especially when dealing with more historic or older figures.

Seikaly: When you tracked down these artists and found out that they're still alive and interested in talking with you, what kind of feedback did you get from them? When you told them what the book was about, what did they say, if anything?

Ferrer: Gratitude, enthusiasm, excitement about the idea, because they're just as aware as I was that such a book did not exist. And as I said, they've achieved various levels of success with their work, but they were just excited to think about being part of the book. There's a great sense of community, not always nationally, but certainly in New York with the En Foco photographers and among the Chicano generation in LA.

But the west coast photographers don’t necessarily know those on the east coast and vice versa. But, they were all intrigued by the idea of seeing their work in a broader context, and trying to thread this cohesive history; that was really appealing to them. They were always willing to help, provide me with what I needed, whether it was permission to reproduce work or fill gaps in information that I didn’t have. That was one of the driving things that helped me, the photographers’ enthusiasm.

© Hiram Maristany, Procession, 1969. Courtesy of the artist.

Seikaly: You talked about newspapers, personal archives of artists who were working but not institutionally affiliated, flyers, posters, and protest ephemera as visualizing 20th century Latinx culture. In the 21st century, do you think that social media functions as efficiently as those analog platforms did in capturing Latinx life?

Ferrer: Social media has become very important. Many photographers use it as a key platform, especially as a more immediate and up-to-date platform as opposed to websites which tend to get old and stale. I end the book with Veteranas and Rucas, an incredibly important example of an Instagram feed established by Guadalupe Rosales that acts as a crowd-sourced archive of images by and about Latinx youth cultures. And there's no filter with social media, no gatekeeper. You can put up the content relevant to you and your community. Veteranas and Rucas has over a quarter million followers, a clear indication that there is a thirst for photographic images that reflect communities and cultures that would otherwise be marginalized.

The big difference between an academic archive and a site like Veteranas and Rucas is the ways the two are organized. An academic archive gets catalogued and preserved, and it's searchable. It’s really difficult to search an Instagram feed. At one point I went through literally every post on Veteranas and Rucas and looked at every single image. Scrolling through took hours but I wanted to see everything that was there.

Eventually, it will be almost impossible to go through all of Veteranas and Rucas for the sheer amount of content there, and I'm not sure what the solution is to archiving important social media sites like that. Sites like this can be transitive in their own way, you know what I mean? It is unclear what will happen to these feeds in the distant future. .

Veteranas And Rucas Instagram archive. Archive para las mujeres de SoCal. Reframing our past for better futures by sharing our stories.

Seikaly: Do you look at institutions like that are focused either exclusively, or include significant holdings by Latinx artists? I’m thinking of the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach. Do institutions have a role to play, or a responsibility, in collecting, in archiving, in further embracing the Latinx artists broadly, and the artists who you’ve helped bring more attention to through the book?

Ferrer: Yes, they do. There are a few institutions that specifically focus on Latinx art, and many of these have been evolving in recent years. MOLAA, for example, was founded as a collection of Latin American art, although in recent years their mission has expanded to present Latinx artists which is crucial given its location. And then there have been institutions like Galeria de la Raza in San Francisco, or El Museo del Barrio, which have long been dedicated to their local Latinx communities. El Museo has gone through a lot of change as El Barrio changes and the Latinx community in New York becomes more diverse.

The museum also has a much higher profile than it has had in its early history. I don't know how much photography they have in their permanent collection but they presented many photography exhibitions in their early history. They maintained a space that they called the F-Stop Gallery. It was really more of a hallway but they showed a lot of work, including by many women photographers. El Museo will soon exhibit work from En Foco’s early days, so it is good to see more photography at that institution.

More broadly, major mainstream institutions are finally paying greater attention to Latinx art – this is a very recent phenomenon. Latinx curators are being hired by major institutions. Marcela Guerrero is at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Carmen Ramos had been at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art and was just named Chief Curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. LACMA has also had Latinx curators.

The curators in those positions can have a major impact on what is seen and how the story is told. Marcella curated the first Latinx exhibition at the Whitney. My hope is that Latinx Photography in the United States will encourage curators nationally to see what could and should be collected. There is just so much potential to broaden how these major museums present the history of photography.

Meet Elizabeth Ferrer

Seikaly: Is there any concern that that is what Latinx photographers are supposed to focus on? I mean strictly defined, social justice-oriented work. Is there any concern that that's the expectation, and that Latinx photographers might be pigeonholed because of it?

Ferrer: Yes, I think that happens with Latinx artists in general. For that pioneering generation of photographers that emerged during the civil rights movement, that was the motivation itself, whether it was to document United Farm Workers or all the inequities experienced by Latinx people in New York. As Latinx communities in the US evolved, and as photography evolved, a new generation emerged that moved away from this kind of direct documentation of protests and political events. But the ethos that these earlier photographers expressed, the sense of ethnic pride and the desire for self-representation, remained. Particularly in the 1980s, man Latinx photographers were focusing on identity-based work, a tendency that was actually broadly seen among art in general in that and the next decade.

I certainly discuss photographers whose work cannot be easily categorized as “Latinx.” One is Chuck Ramirez, who was based in San Antonio and died prematurely in 2010. He made large-scale, color-saturated images of oddball inanimate objects – stuffed garbage bags, plastic soda containers, the insides of handbags, and pieces of meat. Some of his work references Latinx culture, but overall, he was interested in expressing the banality of consumer culture; it could be funny and serious at the same time. I wrote an essay about Ramirez for the catalogue of his 2018 exhibition at McNay Museum, Chuck Ramirez: All This and Heaven Too. And it was interesting to think about his work in the context of Latinx culture, Pop Art, and more broadly in terms of contemporary art.

And then there's Martine Gutierrez, one of the youngest figures in the book who is receiving a great deal of critical attention. A trans artist, she has expressed intersectional identities. In earlier staged portraits, Martine has depicted models in high-fashion poses wearing traditional Indígena dress. For the series I include in the book, she staged mannequins dressed in sex play costumes. So, Martine may touch on issues of Mexican-American identity, or they may not. And I think she feels very free to go in and out, to be very fluid about her subject matter and the way she expresses identity.

As an aside, I curated an exhibition at BRIC earlier this year, Latinx Abstract. It included the work of ten artists and it was very multi-generational; the artists ranged in age from late 30s to 80s. All working with various forms of abstraction. I curated that show specifically to address this issue: the expectation that Latinx artists make a certain kind of art. And also because I don't see these artists in the art historical canon.

If you look at any kind of survey on the history of American abstract art, whether a book or an exhibition, you won't see these names, and some of these artists have been around for five or six decades. Latinx artists don’t feel restricted by these kinds of expectations but the art world certainly still reflects them in the way it operates. And that’s changing, but slowly.

Latinx Abstract. Curated by Elizabeth Ferrer at BRIC

Seikaly: I read your book and Arlene Davila’s book Latinx Art: Artists, Markets, and Politics almost simultaneously, and both exposed huge gaps in my knowledge. They drive home how white, how cis male, how heterosexual western art history and photo history are. These two books expand the art historical canon, and yours particularly chips away at this monolithic idea of who makes photography, how it's consumed, where it's produced and published. And that resonates with makers and audiences alike. I don't think it's hyperbolic at all to say that your book introduces readers to generations of artists and their work that were previously unknown. It's a huge accomplishment.

Thinking of how much you packed into such a slender title, I’m wondering if you would produce a volume on the scale of Naomi Rosenblum’s A World History of Photography?

Ferrer: Economics is always an issue. The University of Washington Press, which is wonderful to work with, took a risk with this project, and I understand the realities of publishing today - a big coffee table type book would not have been feasible. But as I said, this book represents a start and hopefully it will expand into other projects, whether my own or those of other scholars or curators. But you just remind me of one other thing. I don't really delve into this too much in the book, but another big economic issue – one that directly impacts a photographer’s success - is the photo market. Who becomes important or “famous”? How is the work valued

Several years ago when I was in the early stages of my research, I gave a talk at the Society for Photographic Education that dealt broadly with the invisibility of Latinx photography. Of course there is a lot of racism implicit in what work, what artists, get attention. Tied to that is gallery representation. For that talk I looked at the director of AIPAD, the Association of International Photography Art Dealers, and among the thousand-plus photographers that these prestigious dealers represent, I found maybe a half a dozen names that were Latinx.

Seikaly: Yeah, that doesn't surprise me.

Ferrer: So, if these photographers aren't represented by galleries (though more are now), it becomes very difficult to sell their work, especially to institutions. If you have a good gallerist, they’ll work hard to place your work in museums or in important private collections. But, if you don't have that relationship, you're not getting the benefit of that kind of effort and networking and your work probably isn't going to end up in the museum collections. So that has been a big impediment from the get-go for Latinx photographers.

Seikaly: That's huge, yeah. Absolutely. I'm thinking about William Camargo, how he’s so strategic about where he wants his work to be located in terms of exhibitions and private collections, and who represents his work. He’s of the generation of artists who are thinking about the ways in which the capital A art market has predictably failed artists of color. They are leveraging social media and all of the available tools available in a way that might force galleries to come to them.

Ferrer: They do it on their own terms.

Seikaly: Exactly. They're less likely to land in the doldrum where their work is represented, but their gallerist doesn't do anything with it.

Ferrer: Yes, and younger artists, and there are older artists. Artists who may be, say, in their 70s and may still be active and who have this big body of work. Maybe they're not so comfortable with social media, maybe they have a website, but they don't have social media presence and those photographers, I worry about how their work will be preserved and will their work be remembered.

Seikaly: Yes! That's one of the reasons that this book is so important. This single volume effectively defeats any argument about a lack of extant scholarship on Latinx photography as an entry to further study.

Ferrer: I get a lot of notes from students who thank me. That's also very gratifying.

Seikaly: That's not surprising at all. It’s a remarkable book, and I hope that after reading this interview, Humble Arts Foundation readers will make the purchase and spend some time with it. Thanks very much for speaking with me!