Yellow Bird in Banana Tree, 2021. © Tiffany Smith

Curated by Amanda Coulson at TERN Gallery in The Bahamas, “The Other Side of the Pentaprism: Six Photographers in Conversation” shows Caribbean photographers grappling with – and pushing against cultural and historical stereotypes.

Caribbean culture is often envisioned with an outsider gaze. Tropes of the cultural exotic and a land ripe for vacationing illustrate the place without acknowledging its history of entanglement with colonialism and enslavement. The Other Side of the Pentaprism is a beautifully curated photographic counter narrative featuring work from Melissa Alcena, Tamika Galanis, Jodi Minnis, Lynn Parotti, Leanne Russell, and Tiffany Smith.

The exhibition takes inspiration from the pentaprism, the five-sided reflective prism found in a single-lens reflex camera that re-inverts an image, delivering a version of “reality” back to the viewer. The six women artists in the exhibition represent this filter between the Caribbean narratives presented in popular media and history books, and the experiences of those living inside it.

Through a range of approaches, the women in this exhibition question the line between constructed narrative and reality, and the shades of gray in between. I spoke with exhibition curator and TERN founding director Amanda Coulson to learn more about her ideas behind the show (on view through November 13, 2021), and the work within.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Amanda Coulson

A Feeling of Relief, 2019 . © Leanne Russell

Jon Feinstein: The title is a reference to refraction and the physics of manipulating reality — a metaphor for the deceptive way Caribbean culture has been presented by outside imagery. Can you talk a bit about how you conceived of this in relation to the concept behind the show?

Amanda Coulson: As a person from the Caribbean, it’s always been very evident that outsiders view my country, The Bahamas, and region very differently to how we see and experience it from within. Our homes are seen as exotic, fanciful playgrounds that allow visitors to behave in a way they would not in their home country. Meanwhile, we have to live here and deal with stressors of surviving in countries that have been colonised, stripped of their resources and wealth, and are on the frontline of ecological weather events in addition to the usual amount of everyday stress.

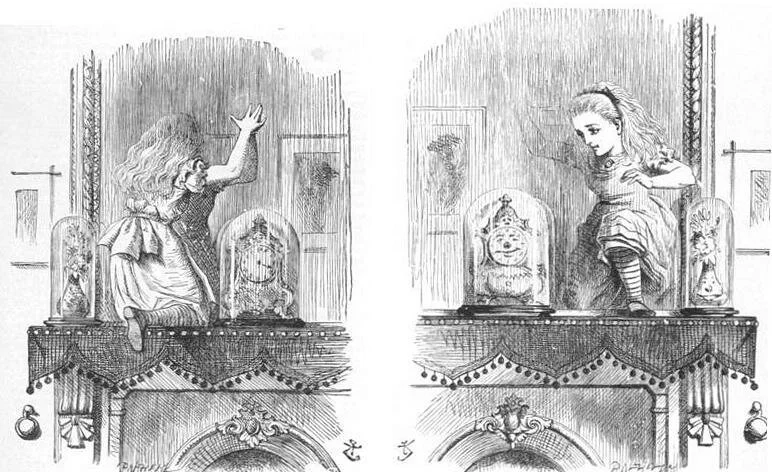

Alice Stepping Through The Looking-Glass by John Tenniel. Mid 1800’s.

And then, one day, you find yourself standing at the bank in your business suit, trying to get a mortgage, and there are people next to you in wet bathing suits holding foot-long pink cocktails—it can be very surreal. This made me think of “Through the Looking Glass,” where there is another world, familiar but different, where the “normal” rules do not apply. The “topsy-turviness” is also a reflection of the dissociation we feel, as locals, from the advertising images reflected back at us which are not at all familiar and are, in fact, very strange.

Pigs are not flying here but they are swimming and that has very little to do with our everyday experience. Mirrors and cameras both pretend to reflect and mimic reality but they actually do not, so that was what I was considering: how we can be fooled, tricked, manipulated, while we believe we are seeing what’s “real.”

I Name Charlotte II, 2019 © Tamika Galanis

Feinstein: I'd love to learn more about your curatorial process. The work focuses on Caribbean artists working around issues of diaspora and much more....what guided your curation/selection of artists?

Amanda Coulson: It all came together quite organically. When I first came back home to The Bahamas a little more than 10 years ago, I was, interestingly, seeing some video but mostly a lot of painting and installation, and not as much photography beyond the quiet traditional landscape or portrait work. I’ve always been interested in the medium since photography was actually my introduction to contemporary art. At grad school, I’d specialized in 16th-century Venetian painting, but later I got interested in early photography and started to collect it, which led me to the contemporary field. It was also in the era of the rise of people like Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Cindy Sherman, Elger Esser, et. al.

After grad school, I went to work at a gallery in Milan that specialized in photography, so perhaps I was looking out for it without consciously doing so. Recently I just started noticing a group of strong women artists, who were using photography in different ways, to unpack these tropes around Caribbean-ness, womanhood, personhood and to question the (generally British) textbook representation of our history. I saw that the work these women were making also spoke to each other, which is why the show is conceived as three conversions between the six artists.

Ellie. © Melissa Alcena

Feinstein: Who was the first artist you curated into the show?

Amanda Coulson: All the work speaks to me, of course, but it was the piece Ellie by Melissa Alcena that started my brain ticking. I was writing something about it and for some reason, I felt like she was a Black Caribbean Alice. Her big bow and her puffy dress contrasted against the dark, lush foliage just instantly made me think of a tea party in the Caribbean forest. She is the yin to the yang of Disney’s blonde, white Alice, as she walks through the rather sinister Tulgey Wood, a Wonderland forest with no end, where people get lost to eternity and which is populated by bizarre creatures, like the Mome Raths.

Ellie is dwarfed by what we would here call “bush” and many of our folktales speak to “sperrits” or “duppies” (in Jamaica) or, in our context, beasts like the Chickcharnee. I love that Alcena celebrates our landscape and people but in a way that is the polar opposite of tourism’s images. That made me think of both Alice’s journey through the looking glass and also of Tamika Galanis’ work, where the central female figure is reclaiming her place in the bush, literally wrapped in love vine, standing in the ruins of the former “great house” whose inhabitants enslaved her forebears. They are both using portraiture but in entirely different and unique ways.

Bird of Paradise, c. 2020 © Melissa Alcena

Feinstein: In the press release you describe the work as "revealing a different universe." How are these artists doing that and what do you think is being revealed?

Coulson: The artists are themselves the looking glass, or the pentaprism, and they are filtering the world that surrounds us, magnifying it, flipping it, re-presenting it to us in new ways. They are showing us what is there if we choose to see it, a little like waking up from the matrix. So they are forcing us to see what is real, to not accept what we have been told is the truth.

The figure in Galanis’ work, for example, is the re-creation of an actual historical figure, a woman named Charlotte who was part of a famous uprising of the enslaved in 1831. We have been told in school that a man named “Black Dick” was the leader, but Galanis’ delving into the archives tells another story. Her work speaks to how often women have been left out of the narrative.

Top: I Name Charlotte III, 2019 © Tamika Galanis

Bottom: I Name Charlotte IV, 2019 © Tamika Galanis

When we’re presented with another truth, it might look strange, comic or unusual to us at first. So the universe these artists are presenting us with is one where women are reinserted into historical narratives from where they have been excised—where people of color are seen as beautiful, soft, triumphant; where the Mammy ain’t gonna serve you food but will take care of her own needs first; where we see and accept the damage to ourselves, both as human beings emotionally and to our countries and homes physically, and realize that there is work to be done to heal before we can expect society to rebuild and thrive sustainably.

From a very simplistic standpoint: for centuries we have had hurricane after hurricane wipe out our settlements and we build on the rubble. This is evoked in Leanne Russell’s work, in which she overlays negatives from the great Abaco Hurricane of 1932 with contemporary images from Hurricane Dorian, underscoring this continual cycle.

We’ve done this over and over again and the world barely notices—only now that it is affecting them too—and yet we are expected to “be resilient.” Metaphorically we are building on the rubble of the colonial era, on bad foundations, but we are chastised and belittled for not being more “first world.” Yet while our economies and infrastructures are laughed at, we’re also consistently told that we are “living in paradise.”

Enslaved House. © Lynn Parotti

Feinstein: How does this work bring sense and balance to previous conceptions/illusions of "the real"?

Amanda Coulson: I’m not sure it brings sense, necessarily, but it certainly brings balance to an image that has been skewed by history and tourism. At a very basic level, the Caribbean is a real place, not a fantasy land, with amazingly diverse people and complex histories that have been simplified, dumbed down or erased. Lynn Parotti’s The Enslaved’s House series, for example, shows images of a crumbling, humble domicile on the island of Exuma overlaid with a sumptuous manor house in the UK formerly owned by the de Rothschilds, the family who loaned the British government 20 million pounds to “reimburse” the landowners for their loss of their “property” when slavery was abolished.

It appears, in some of the images, as if the palace is rotting from the inside and it speaks to the decadence inherent in the period and the unsustainability of such a lifestyle. The series also comments on issues of land ownership: the Exuma property was key in a landmark case which set up what we refer to in The Bahamas as “Generation Properties,” where descendants of the formerly enslaved have a right to retain and maintain the land. It’s interesting to think that those descendants are still tending the same patches that their forefathers were forced to nurture, whereas the manor house must now be sustained by the UK’s National Trust and paying tourists. Of course, it also speaks to what we choose to care for and venerate and what we try to forget or erase.

Left: Enslaved's House IX, 2016. © Lynn Parotti

Right: Enslaved's House XXIX, 2016. © Lynn Parotti

Feinstein: One thing that stands out about this exhibition is the discussion of people and cultural references as "props." In the statement for the show, you describe a longstanding colonial tourist gaze — one that dehumanizes and aestheticizes culture. What's fascinating about so much of the work you selected is that it works as a kind of subversion of these props. Flowers and other ephemera are reimagined with a riff and nod of reclamation. Can you talk about this?

Coulson: Like any stereotype, there is a grain of truth behind the imagery. Yes, The Bahamas is a lush space with flame trees and shrubs that flower all year; yes, we have fruits like mangoes, dillys, soursops, breadfruit and avocados (or pears, as we call them) and, yes, we do make local fabrics that are colorful with floral prints. So I think the difference is not so much the prop itself, but the agency in using the props and in positioning oneself.

You really see this in the works by Jodi Minnis and Tiffany Smith who both use sell-portraiture, installation and sculpture to mock the categories that they would normally be relegated to. Minnis plays with the expectations that she is fully aware people have of her: to be nurturing, to be able to cook, to be available to hold one’s secrets and sorrows.

The dehumanization and desexualization of Black women by the “Mammy” figure, whose sole purpose is to make us feel safe, cook, clean and care for us, is challenged by dressing herself as this archetype, and she takes back her own power, especially in the work entitled “No!” where the “Bahama Mama” literally hits back.

Salt Lime and Pepper | Salt Lime and Pepper 2, 2021. © Jodi Minnis

In the attendant sculpture, the eponymous salt shaker, cast in black resin, stands atop a truncated rolling pin and proclaims “I can’t make pepper jelly.” Smith meanwhile, who is lighter skinned and speaks with an American accent, is caught between tropes: in The Bahamas, she is perceived as a tourist and treated as such (“Miss, you want your hair braided?”) and so she casts herself as “the traditional tourist,” wearing the ubiquitous straw hat and raw pink with sunburn. Smith almost longs to be this character, enjoying “paradise” as only a tourist can because we’re too busy on the service end. In the US, however, she is seen as “exotic” and constantly misidentified, often as Latinx.

In her series For Tropical Girls who have considered Ethnogenesis when the native sun is remote, she plays with those personas, presenting herself as a super-hyped up Carmen Miranda, taking the usually signifiers of our Caribbean identity but presenting herself as regal and empowered, not unlike an 18th-century portrait of monarchy. Smith is challenging the viewer to know who she really is, which is all of these women, combined, as our identities are manifold and complex.

Study 6, 2014 © TIffany Smith

Feinstein: How do you hope this exhibition/the work within it will change perceptions and representations of the Caribbean?

I always think of George Clooney’s monologue at the opening of the film The Descendants: “My friends think just because we live in Hawaii, we live in paradise. We’re all just out here sipping Mai Tais and shaking our hips and catching waves. Are they insane? Do they think we are immune to life? How can they possibly think our families are less screwed up, our heartaches less painful?”

I believe that with our creative output we articulate our heartaches, as well as our joy and our pride. So with any artistic or creative output, my hope is always that it will chip away at the prevalent image of our country as one where Bahamians are limited to “characters,” such as bartender, jet-ski operator, croupier or shady banker, who we are all whooping it up under a palm tree drinking Sky Juice and allow the world to see us in our true skins.

Unbelievably, I am often asked, “Is there art in The Bahamas?” which is so condescending and should actually be translated into, “Is there the kind of art that we consider art in the Bahamas,” so I hope this show—and others we are staging—would bring an end to that kind of question and show that we are indeed able to conceptualise, articulate, envision and create on a world-class level.