Seeing Being Seen: A Personal History of Photography. Cover Photo © Will Wilson

Michelle Dunn Marsh, one of photography's foremost champions speaks with Humble's Jon Feinstein on her new book, her love for the medium and its makers, and why visual literacy is more important now than ever before.

I first met Michelle Dunn Marsh at a random Chelsea coffee shop in NYC around 2008 when she was Aperture Foundation’s deputy director, and co-publisher of Aperture magazine. Humble's co-founder Amani Olu and I, a year into launching our platform, were Wayne's World "we're not worthy"-ing our luck in landing a meeting with her to discuss a potential collaboration. Dunn Marsh was direct, immediately inspiring, and encouraging, and made a significant mark on many aspects of Humble's vision in the years that followed.

Fast forward to 2013 and a move to Seattle. I was lucky to collaborate on many projects with her at Photographic Center Northwest, where she served as Executive Director through 2019. Michelle brings a critical and empathetic eye to photography, and her multi-decade support of its practitioners is nearly unrivaled.

Michelle's soon-to-be-published memoir Seeing Being Seen (Minor Matters Books) chronicles her life and work as a book designer, cultural producer, and publisher. Warm personal anecdotes about her experiences in the industry and working with some of photography's late and living legends direct the narrative. Punctuated by portraits of her by Stephen Shore, Larry Fink, Sylvia Plachy, Will Wilson, and Adrain Chesser, and work from her covetable, personal photography (and vintage car!) collection, it's a glimpse of her life and career over the past 25+ years.

With a few weeks until the April 1st, 2021 deadline to achieve the book's presale goal, Dunn Marsh and I caught up to dive into the book, her life, our shared passion for photography, and kinship as fellow Bard College alums.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Michelle Dunn Marsh

1976, third birthday. Photographs likely by my mom, Joyce Dunn.

Jon Feinstein: You’re not, officially a “photographer,” yet your life is dedicated to the practice and love of the medium. What was the first picture that made you fall in love with the medium?

Michelle Dunn Marsh: The first photographs I fell in love with were snapshots from my third birthday. Mrs. Graybeal, the neighbor, made me a giant cake in the shape of Winnie The Pooh, and I was over the moon. I knew her well and really loved her. She died very young. So even as a kid I would go to the album where these photographs lived, to look at them, and think of her.

The first work of art that held me was an oil painting by Abby Bender, a dormmate (and still a dear friend) from my first year at Bard. She’d done an assignment, and it was hanging in her room in the Ravines. She needed to complete another assignment, and intended to gesso over the painting and re-use the canvas. I panicked—seeing that painting every day brought me such peace and calm. So I asked if I could buy it, though neither of us knew how to “value” art.

Abby started with, “just buy me a canvas, that’s what I really need.” That didn’t seem enough to me—it didn’t account for her time, her labor, her genius. So we tried again, with her suggesting an hourly calculation at minimum wage. That still didn’t feel right to me, though I was as broke as she was, and couldn’t even afford the $16.00 she was proposing. In the end I think we settled on $40. I made the first “payment” by buying her the canvas for her next assignment, and I think paid the balance in $5 increments. It needs to be re-stretched on a frame, but I still have, and still love, the painting, and have three more by her.

Once art pierced me, which photography already had, the melding of the two was practically inevitable.

Elinor Carucci, Two Eyes, 1993, C-print, courtesy of Elinor Carucci

Feinstein: At what point did you realize you wanted to dedicate your life to shaping, designing, publishing, and honoring photography?

Dunn Marsh: As Americans, I think we have an attachment to “falling in love and living happily ever after.” Of course, life teaches us it rarely works that way. So I would describe it more as a throughline of choices, rather than a point of realization.

In 1991 I went to Bard; you ask about that later. In 2001 there was an earthquake in Seattle, and then 9/11 in New York, and then Michael E. Hoffman (Aperture’s director of 35 years) died at the age of 59 after a brief illness. I managed to be in each city for each calamity. I’m still unpacking the shifts and losses of 2001. A lot of people turned inward. I jumped on many planes to preach the good word that, as my sister once wisely stated, “the continuation of this art form of photography is never guaranteed.” Why was that a responsibility I felt so deeply at that moment? I was recently married, a professor in a tenure-track position, a working book designer.

My home life was what I’d always wanted. But photography felt fragile and in need of support, and through it I felt connected to socio-political issues, climate, environment, humanity. It was a portal to “the surface of life,” a paraphrase of something Robert Adams once said to me and has written about. So I did all I could for the medium, and for the institution that had most firmly rooted me in it. Sometimes to the neglect of almost everything else.

Then in 2011 I was laid off from Aperture at the beginning of the year, and my marriage crumbled at the end of the year, and 2011-2012 was excruciating the whole way through. But so was 2001. So you gain some tools to navigate. My stepson was a huge part of my survival, as were my friends. And there was still photography. Bruce Davidson and Mary Ellen Mark called with tips about possible jobs in New York. Sylvia Plachy, refugee and immigrant and soulful eye, helped me process loss just by owning it.

I was working with Amelia Davis, Jim Marshall’s assistant, the beneficiary of his estate, and manager of his archive, and in 2012 the release of a Jim Marshall Rolling Stones book with Chronicle, a corresponding museum exhibition in Seattle, Steven Kasher’s gallery exhibition for Jim in New York, and the Jack Daniel’s-sponsored installation of Jim’s work in Austin, Texas, catapulted me forward with Jim’s tough-love voice in my head saying “I love you, f*ck everything else, keep going. “ And I did.

Michelle holding Lisa Leone’s Here I Am. 2014 Central Park, New York, photo by Brandon Remler

Feinstein: Why a memoir and why now?

Dunn Marsh: Well, COVID—I went from 2-3 trips a month to, as of March 1, a full year without being on a plane. It was like a time machine was cranking out hours, like bubbles, so I thought I’d catch a few to write, and see what happened.

As American culture is grappling with the mythologies and realities of its histories and its present, I am seeing binaries, dissonance, and scarcity. Specific to photography, there’s been a tearing down (sometimes valid, sometimes not) of the past, without acknowledging that it is difficult to succeed in a structure you aim to be a part of if, in fact, it no longer exists. I am at my very core polyvalent—both/and, not either/or. So I support the expansion of vision and voices, and I also hold respect for practitioners who have contributed to the brief and substantial histories of this medium in the United States.

I have learned a lot from straight, older white men, because they were the majority population in many of the spaces I began working in, and they were open to teaching me. I have also learned from the Black Panthers, radical faeries, Zionists, environmental conservationists, Bengali women—a plethora of other humans. Seeing Being Seen, through a professional chronology but also through twentieth- and twenty-first-century photography—holds the complexity I value in life and in visual art, together in one space.

I’ve spent my career in the fields of photography and publishing, which have been largely racially-homogenous, middle to upper class, well-educated spaces—and I largely perceived them as safe. Yet in the highest levels of leadership (in New York and in Seattle), I have had to fight misogyny and identity erasure because being smart and female and white and brown and first-generation American and a car-loving farm kid and a New Yorker is all just a little too much.

So I have had to pick and choose what parts of myself I will present, and what I will reduce, to sit at the tables of power. In 2013 I vowed to never again make myself smaller, or allow others to make me smaller, to appease people’s discomfort. In the fall of 2016, after that year’s presidential election, I had a frighteningly simpler goal: to physically and mentally survive.

I hope this book, now, will assist in inspiring the future, and engaging the present, to advance how we do the work we do—and expand who is doing it by embracing abundance, making space for more.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled, from "The Kitchen Table Series," 1990/print 2010. Light Work edition of 100; courtesy of Carrie Mae Weems

Feinstein: Tell me about the title “Seeing Being Seen”

Dunn Marsh: There is, of course, a bit of wordplay—I have made a living seeing, and have definitely served in very public roles. Has my being always been seen? Well, no. But in this third decade of the 21st century, there seems to be a bit more effort in some spaces to try and work on accepting people in their totality, regardless of the boxes we often, even in the creative sector, try to squish people within.

Eugene Richards, Firefighter sitting alone in the rubble, World Trade Center site, from "Stepping Through The Ashes," 2001/print 2016. Not editioned, courtesy of Eugene Richards

Feinstein: My understanding is that the photographs included in the book are not only ones you love, that are important to how you think about the medium, but are also images that you have a personal connection with… can you talk about the image selection for the book?

Dunn Marsh: In choosing images, I thought about both the photographs and the individuals who made them, and then their intersections with key points in my life. For instance, the first print I was given by Eugene Richards is Blind Elder from Ghana, which I love. But the print I chose for the book is Firefighter in the rubble from “Stepping Through The Ashes,” because that photograph holds the breathtaking chaos and quiet of what was for me a very difficult year.

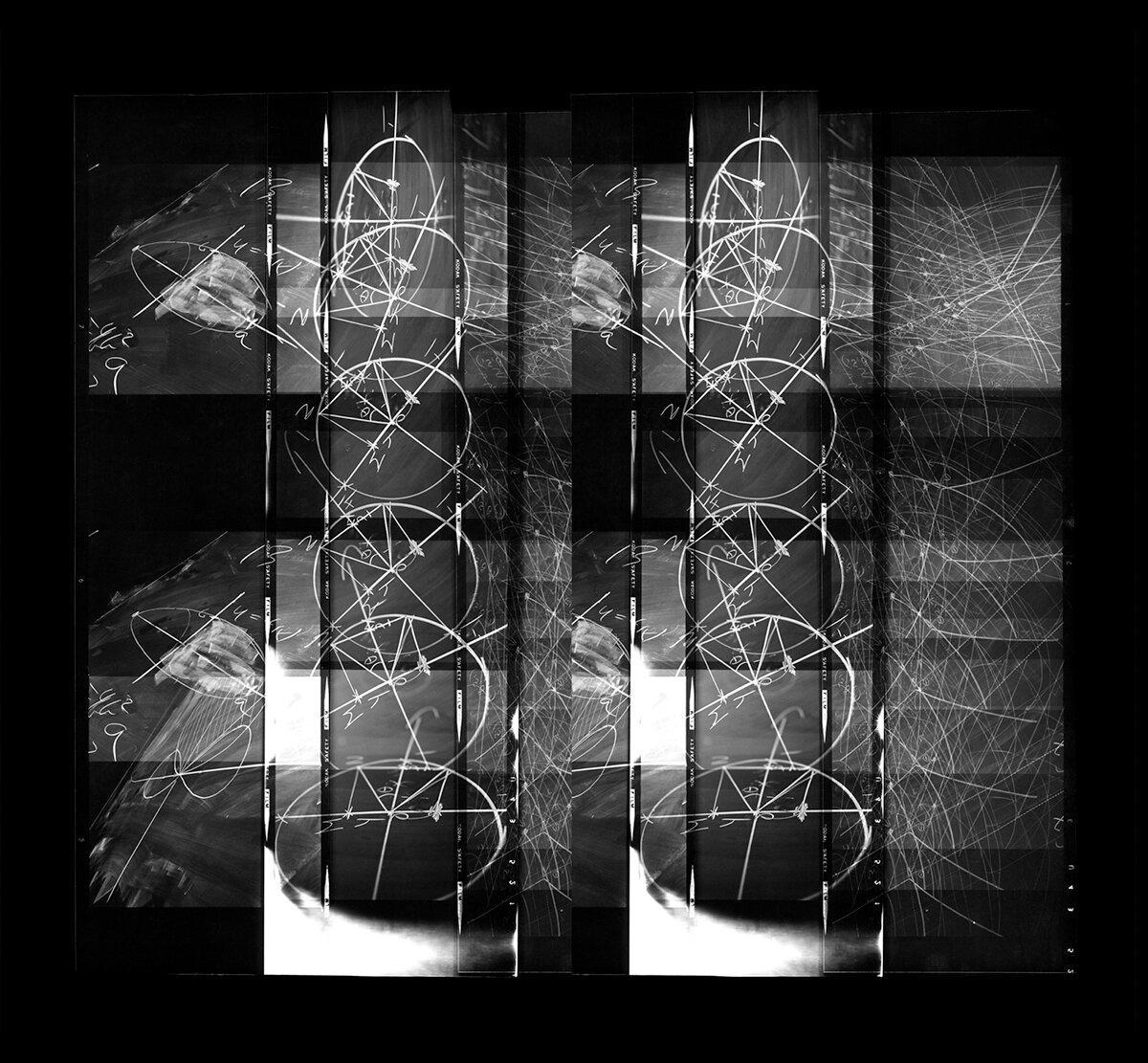

Paul Berger, Mathematics #55, 1977, vintage gelatin-silver print, not editioned, courtesy of Paul Berger and G. Gibson Gallery

Feinstein: Joan Liftin describes you as a “throwback to the days when publishers really gave a damn!”

As long as I’ve known you, working with photography and photographers has been so much about a true sense of and respect and care for the work, for the medium, for photographers and their practice.

Dunn Marsh: I take the process and completion of books seriously, and the work of creative practitioners seriously. I am transparent with the authors we work with that we are engaged with them in the bookmaking process. Sometimes that’s one or two small suggestions; at other times it’s a longer evolution with multiple directions explored to hone in on what feels right. If the book is going to outlive us all, which is the goal, then it has to be able to communicate on its own, and it can be a bit of a process to arrive at what it, and the author, and the work want to say together.

We’re committed to originating primarily hardcover books, printing them with the notion of art reproduction in mind, and carrying through an understanding of the craft of photography to the craft of bookmaking. Our books are expensive to make and the pre-sales process is a challenging one. We have, at the most, done six books in one year. When I was a designer at Aperture I worked on ten or so books at a time, plus other projects; as an editor at Chronicle it was more like twenty at a time in different stages. The emergence of the book from the work is my favorite part of the publishing process, so with Minor Matters, we’ve constructed a model that makes time and space for that. On the other hand, we can only keep doing it if books do, indeed, move into the marketplace and generate income. So the pre-sales process is equally important.

The amount of time that can be spent wrestling with a project is different for every imprint, just like the priorities of the books themselves might be a little different—some of my colleagues are fulfilling different visibility needs, or career needs, by getting books into the marketplace quickly, or at a lesser price point, or doing very specialized production at a much higher price point.

I think sometimes it is surprising to people from outside of publishing how collegial we are. But we all love the same thing and try to support each other. Everyone succeeding means more books to consider….

Feinstein: For early partners, the book comes with “Reading Photographs,” a workbook on visual literacy, published by PhotoIreland. Why is visual literacy so important to you?

Dunn Marsh: The Alice-tumble down the rabbit-hole of visual literacy started with a 1957 issue of Aperture I probably picked up at the Strand, or some other used bookstore, about ten years ago. Largely written in Minor White’s tongue-in-cheek voice, the editorial felt so appropriate to the 21st century and the glut of imagery that I was motivated to read further. Coming from a design/editorial eye and not as an image-maker, I really appreciated the articulation of ways to feel a photograph, and also to distinguish that from both how it was made, and what the viewer is literally seeing.

I loved studying history, and may have been diverted exclusively to that discipline if Fernando Gonzalez de Leon had stayed for more than a year at Bard—his influence is still with me. I am always inclined to share the history of graphic design or of photography when I am given the opportunity! So it began with a masterclass to share this process of seeing with high school students through the YoungArts program.

And their responses were amazing. The more I studied, the more intrigued and alarmed I became about how the brain’s processing of imagery and memory carried dangerous consequences when it came to matters of misogyny, systemic racism, and homophobia. At that point, a lightning bolt struck, and I’ve been incorporating it into almost everything I’ve done since—I feel so strongly that we have to own the subjectivities of our seeing if we’re going to become a country that can engage in dialogue, and respect differences of opinion (noting that they are opinion and not fact, and what the difference is).

Charlie Rubin, I Love You Rock, 2012, folded archival pigment print, AP, edition of three, each unique, courtesy of Charlie Rubin

Feinstein: What was the process behind developing this visual literacy workbook and why was it important for you to develop it?

Dunn Marsh: The workbook came out of a talk I did for educators through PhotoIreland in Dublin two years ago. Afterward, one of the attendees said something along the lines of, “ wait, what do we do now? Where’s the website, the workbook, the resources to process this further? You’re just going to reframe how humans should see, then jump on a plane?”

He was so right. Another lightning bolt! The summer sessions we did at PCNW which you attended, Jon, were the dry run of what is soon to be a publication released through, appropriately enough, The Critical Academy, a program of PhotoIreland. Co-publishers of Seeing Being Seen will get a complimentary copy. I’m so thrilled that Angel and Julia at PhotoIreland saw the significance of this methodology, and are committed to sharing it as a teaching tool.

My sister Anastasia Van Dyke and her 1968 Camaro, 2007.

Feinstein: I’m not sure if this is relevant for the conversation, but I recall you are also a car collector!

Do you see any relationship between these two passions?

Dunn Marsh: : ) I am not a car collector, but my father was—I grew up with twenty-six cars in various states of mobility and disrepair, about six of which were truly functional and driven on a regular basis. My 1950 Studebaker was one of the other twenty. I asked for it to be mine when I was about nine years old. It was finally restored and licensed as road-worthy in 2008.

My sister inherited our mom’s 1968 Camaro, but due to her space restrictions, that car lives at my house also, so I keep it fed and watered and running as best I can. My father enjoyed working on the cars, driving the cars, and preserving as well as sharing them as evidence of American history. That custodial but also functional notion very much carries through to how I think about the photographs I’ve been lucky enough to live with.

My 1950 Studebaker the year we completed restoration, 2008.

Feinstein: Back to Minor Matters: You founded the imprint as a practical approach to publishing - get funding upfront, but pivot on the rewards-driven Kickstarter approach, somewhat more directly….How has this business model worked over the past few years?

Dunn Marsh: We were less interested in the Kickstarter rewards model (and lawyers advised us to absolutely avoid the term “crowdfunding”) than in the Adams/Weston school of funding portfolios through pre-selling them, and intersecting that with the obvious social embracing of e-commerce. Naming people in the books really goes back to the early issues of Aperture, and to forming a historical record of individuals taking collective action.

Endia Beal’s Performance Review - recently published by Minor Matters Books. Book photograph by Joe Freeman Jr.

Feinstein: What have been some of your biggest learnings over the past 8 years?

Dunn Marsh: We’ve certainly learned a lot. We’ve seen that selling the first two hundred copies is the hardest, so we spend a little more time with the artists trying to gauge if we can secure bulk sales or support to move that along sooner. Either way, the process requires hustle, and a bit of thick skin, and repetition, so we have built out a toolkit to prepare our authors for the slog. Even with that, it’s challenging! But the reward of holding the book, and the true community engagement that all the co-publishers feel when receiving a book they’ve been a part of, is golden.

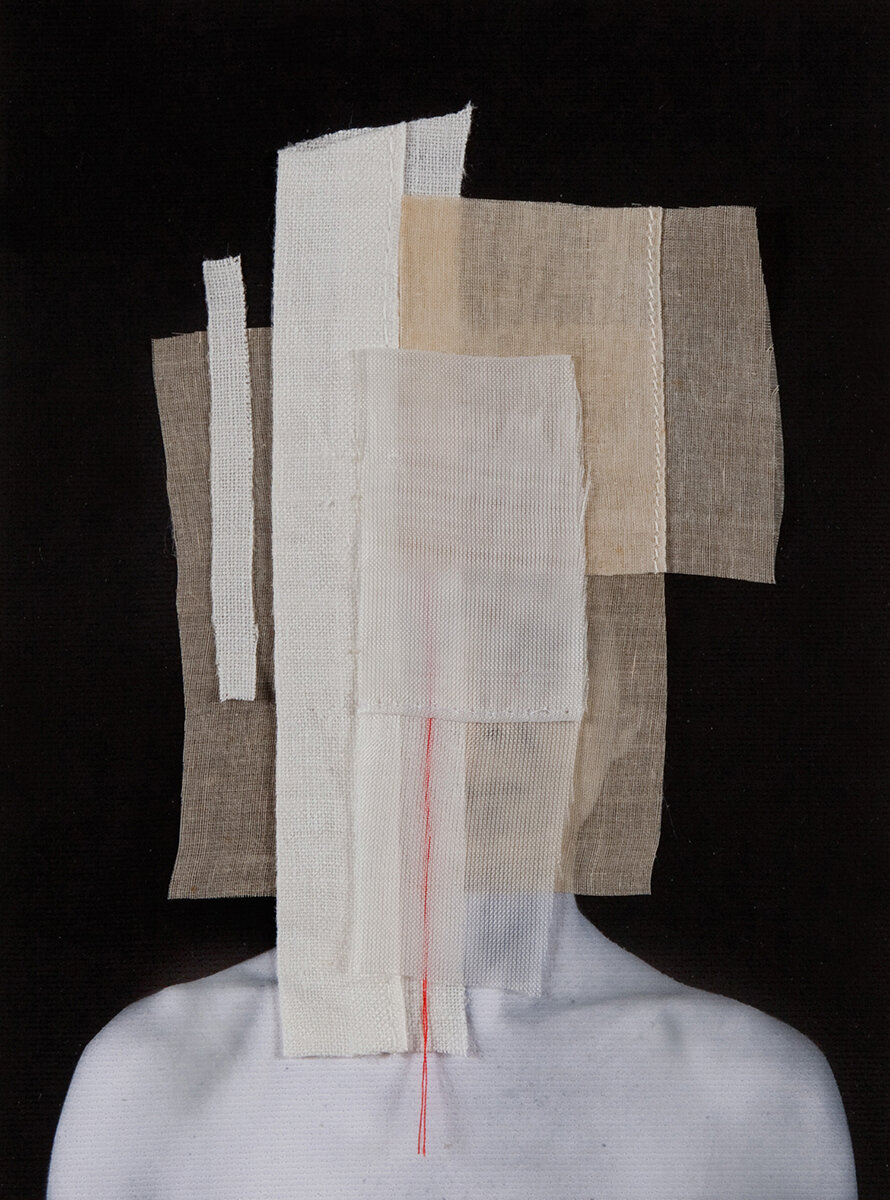

Marina Font, Untitled, from the series "Architecture of The Mind," 2017, each unique, courtesy of Marina Font and Dina Mitrani Gallery

Feinstein: The (digital) landscape has impacted so much over the past decade. Has this impacted your business model?

Dunn Marsh: One of the greatest shifts, since we started, is the changing scene of photography-focused media: no more Photo District News, American Photo, PopPhoto. That’s massive—we often had press coverage in at least the first two of those three, going out to tens of thousands of people who paid to get content. The paid part is significant—we’re now often trying to sell people a book through portals or publications they access for free. It still works, but sometimes it feels more challenging to build the case for why this is worth your $60. I believe there’s an up-and-coming generation who truly values books—what they are willing to pay for something that weighs upwards of 2 lbs, and that they may have to lug around for some foreseeable future, is another story.

Less of a lesson, but a saving grace of 2020, has been that after eight years we have a backlist. When you’ve been publishing for a while you have more book options for audiences to purchase, and so sales can be a little more consistent because there’s more to choose from. In addition to four new books, we reprinted three titles in 2020, the first time we’ve done that. We know that there’s interest in those books, so while it was a financial investment to do so, it felt less risky because we have clear data from our buying audience that those books will find homes over time.

Paul Strand, Wire Wheel, 1917, platinum print by Richard Benson, edition of 100. Courtesy of the Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Feinstein: You’ve been a huge mentor to many - did you, in turn, receive any helpful feedback re: Minor Matters along the way?

Dunn Marsh: Chris Pichler of Nazraeli Press gave me very important feedback a couple of years ago when I’d asked to have a conversation about the viability of what I was doing. He said, not exactly in these words, that I’d demonstrated my prowess as a visionary, and now I needed to do the same as a businessperson—because that was the only way I could continue, and it was imperative that I continue because nobody else was making the books I was making.

His clarity was so valuable, and something I’ve really taken to heart in the last two years. A lot of opportunities would be lost if Minor Matters did not survive—its health as a business serves not only the books and their authors but its, and my, continued existence. Coming from the non-profit sector where we sometimes put “mission over margin,” I’ve seen the dangers of that, as well as only putting margins first. So I have become more aware, as we mature as a business, that we have to hold both vision and continuation in alignment, and that is not a position of compromise, it’s an expansion of acumen and integrity.

The Cover of Jenny Riffle and Mille Landreth’s book It’s Raining… I love you" recently published by Minor Matters Books

1993 set up shot in my dorm room at Bard College, photograph © Don Hamerman

Feinstein: Your approach is highly curated, with a limited number of releases each year - how do you go about deciding to make a book/ work with an artist/ take on a project?

Dunn Marsh: Oh, a combination of months or years of observation, conversation, chemistry, astrology, world events…. : ) Increasing transparency around our decision-making process is one of my goals of 2021 because the mystery around that with any publisher is I think always a little frustrating for potential authors.

We kicked off with a solid decade of potential projects, some of which we’ve made, some of which have been made through other publishers. There’s just a few projects left from that initial wishlist, and in the last five years new projects have taken hold, as they should. Because of the flexibility of our model, I hope our list is always a combination of long-discussed projects and unexpected gifts of serendipity. As to who we work with, we look for craft, humanity, distinction (in many facets), and contemporary resonance.

Steve (McIntyre, my business partner in Minor Matters) and I also launched a consulting site called Book Pitch to give visual authors really specific, market-considered feedback on projects, precisely because I can take on so few, but I believe that there are more worthy of existence, in some form, that we’d like to assist in facilitating.

Stephen Shore, graduation, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, 1995. Unique; courtesy of Stephen Shore

Feinstein: As a fellow Bardian, I’ve always felt a kind of Bard-kinship with you. It was a place that dramatically impacted how I think about photography + the creative/curatorial process and I’m interested in how it shaped your career, thinking, and creative philosophy….

Dunn Marsh: Oh my gosh, in pretty much every way! Bard challenged my very being, my spiritual platform, my relationship to writing as a profession and/or vocation, and my introduction to art history, photography, architecture, and design.

From the “Language and Thinking” workshops at the beginning of freshman year, to classes and chapel and typesetting for Bruce Chilton, to every conversation with Chinua Achebe, to moderation with Nancy Leonard (who bravely accepted me as a moderation candidate though I was already invested not in the words alone but in their visualization), Bard impacted every level of who I was, and to a large extent who I am.

I feel grateful that I ended up in an amazing, challenging place—though I’d chosen it largely because of photographs of people sitting under trees reading books! I wish I could say it was deeper than that. It wasn’t. But when I settled into understanding that the best component of Bard was that it was asking me to make of it what I felt I needed, new universes opened up before me. I remain incredibly aware of the opportunities, the generosity, that was granted to me there. It was a rich beginning to the adult I have become. (Happy 80th birthday this week, Larry Fink. And indeed, you were not this body—you were so much more. RIP Barbara Ess.)

Barbara Ess’s I Am Not This Body - a book Michelle Dunn Marsh designed during her days at Aperture

Feinstein: The past 2+ decades that mark your dynamic career have seen dramatic shifts and evolutions in the medium and how we experience photography. What’s been most exciting to you about these shifts

Dunn Marsh: I can produce a hardcover book one at a time! That is seriously insane considering where I started, character counting on an Apple IIe in 1986. I can’t earn a great deal making and selling a book that way, but I can do it. That is massive as an opportunity. In 2019 I realized a writing project I’d been working on for twenty years through a print on demand book for my family; I released it to the public in 2020. In the end, I’m not sure even twenty people bought it.

But it doesn’t matter—I had the ability, for a few hundred dollars, to see work in book form. I hope every enthusiast photographer gives themselves this gift, with some guidance and editorial involvement (I’d hired an editor for my own personal text project). It feels SO GOOD!

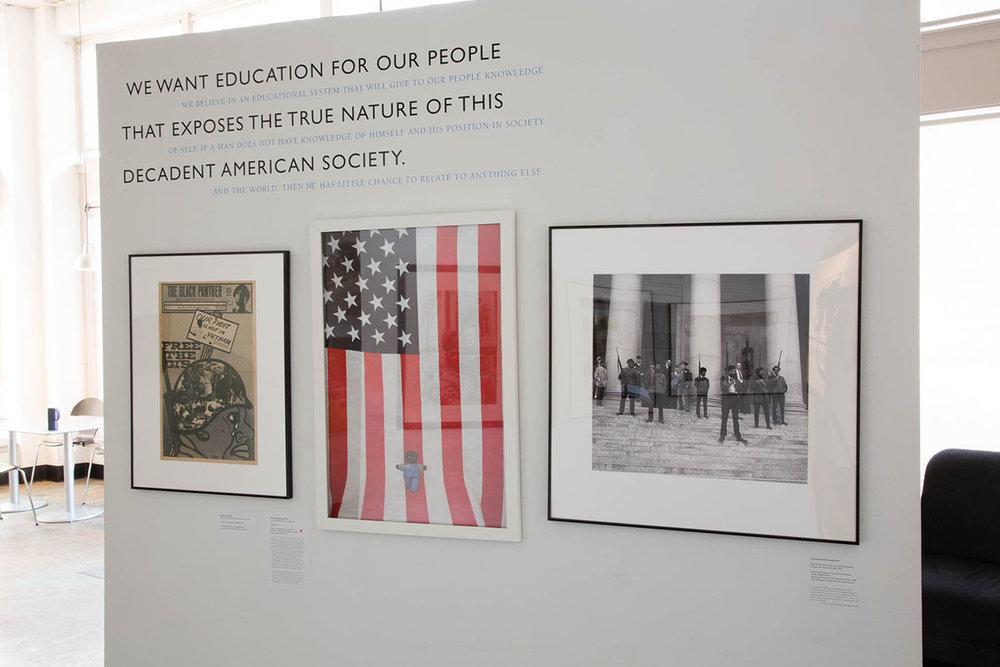

Left to right: works by Emory Douglas, Ouida Bryson, and a historical image by an unknown photographer. From the 2018 exhibition “All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party,” curated by Michelle Dunn Marsh at Photographic Center NW. Installation photograph © Lilly Everett

Feinstein: What’s “stayed the same” with just a new technological packaging?

Dunn Marsh: Intention and craft. It took me longer to really learn the craft because at Aperture, where I began, the intention and end result drove every reading of the image. Now people can, with expensive tools or with knowledge, obtain precise technical perfection of good, yet sometimes boring, photographs.

Emotion, point of view, intellect feeding into the instinctual moment of clicking the shutter really do still matter—maybe now they matter most of all because the “technical packaging” can be so automatically good. Why are you making this a picture? Why do you care? Why should I? Who are you and what are you saying and why does that matter? These questions remain essential.

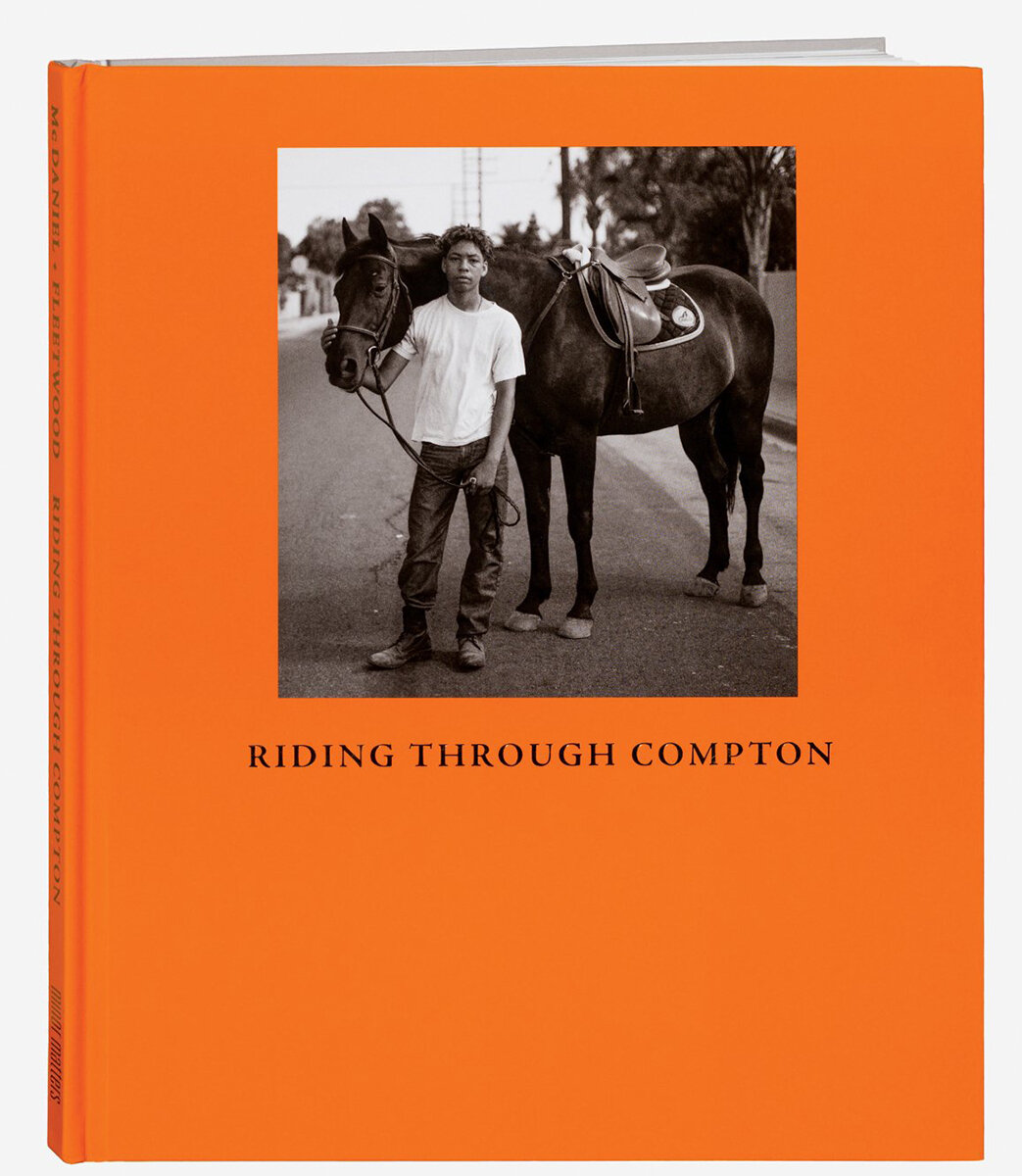

Riding Through Compton. Photographs and formal portraits by Melodie McDaniel with interviews by Amelia Fleetwood conducted with participants of the Compton Jr Posse riding program. Published in 2018 by Minor Matters. Book photograph by Joe Freeman Jr.

Feinstein: What do you think still needs to change

Dunn Marsh: Photography has in certain sectors been slightly more fascinated with the how than the “why” and the “how” remains relevant, is perhaps MORE relevant as fewer people can access it on a craft level, but the marriage of the two, the how and the why, remains elusive.

Certain populations fetishize the darkroom, alt processes, techniques of the “how.” Those have never been easy skills to obtain. They used to be necessary; now they are optional. And so there is a fetishizing of digital, or film, of Photoshop, or not, of type of lens or type of camera, or scanner. All on the how. Mastery of the how expands the toolkit—are you hammering to get more familiar with the hammer? Or are you hammering to build something?

The why still matters—why the image, why the physical form you are giving it. It’s the marriage of the two, the understanding of the history, the craft, and the desire to make an image and perhaps give it a specific object form that has gone out of fashion a bit, but to me feels even more relevant.

Daniel Carillo and Eirik Johnson, from the series "Unfolded," 2016-2019. Daguerreotype, unique, courtesy of Daniel Carillo, Eirik Johnson, and G. Gibson Gallery

Feinstein: In closing, bringing things back to you, and your practice specifically, what keeps you doing what you're doing?

Dunn Marsh: Hmm, now THAT feels like a solid question from a Bardian! Razor-insightful and nearly impossible to answer. Isn’t that the essence that keeps us continually probing, searching, studying, responding?

Feinstein: Ha! I was concerned that it might sound too generic. Maybe that’s the Bard self-questioner in me.

Dunn Marsh: The short answer is, love, curiosity, and the realization of the next project. The questions, the challenges that come up, the discovery of a human who has created something searing that we can assist in witnessing through a book—teasing out the best way to do that, wrestling with if we will find an audience, and how to give the project its best chance at doing so so another book will be born.

Examining my photographic history, the people I have been privileged to encounter, the projects and panel discussions and exhibitions I have learned from, has also shown me some new routes, including project development, and mentorship of others so that our American population is better represented in all facets of photography and publishing.

The photographic medium is the most visually accessible of any art form of the twentieth or twenty-first century while remaining a strong, craft-based, evolutionary medium. I could teach the 182 years of its history just up to my own lifetime and never run out of things to say or explore, never run out of a sense of urgency to share the knowledge of the practitioner, the image, the print, the book. So I guess that is why I’m pausing to write some of this down. I don’t want to forget. And I don’t want our field to forget, either.

I think the process of honoring the history of photography, my history in photography, is giving me some peace, instead of fear, around its evolution. I am secure in my role as a publisher and serving as a historian, a space that continues to feel right for me as the medium shifts. But, surprise! Then a photographer presents something intriguing, as happened yesterday, and I think, oh—I may still have something to add to the present.