© Alex Christopher Williams

Alex Christopher Williams’ new photobook Black Like Paul explores the complexities of race, masculinity, and what it means to pass as white.

A child of interracial marriage, Alex Christopher Williams stands astride two worlds - one white, one Black - each framed by race as a social, economic, and cultural construct.

Williams passes for white. Though the definition has expanded to include ethnicity, caste, social class, sexual orientation, and gender, from a genealogical perspective, passing describes biracial people who identify with or are perceived as belonging to a different racial group based on their appearance. Across the vast and violent span of American history, passing was a survival technique that granted some Black people access to education, employment, and relative safety before the law.

Black, Like Paul, Williams soon-to-be released book produced by Kris Graves Projects’ new imprint Monolith Editions, focuses on the photographer’s experience of navigating racial hybridity. Williams strives to understand his father Paul’s experiences as a Black man, and by extension, that of many men in his immediate and ancestral family and community. Looking at the book, readers may momentarily stand in Williams’ shoes, looking into a world that is familiar in some ways, and unknowable in others.

We recently spoke about going unnoticed in a world that regularly degrades the bodies of Black men and boys, and using photography to access heritage that is challenging to inhabit.

Roula Seikaly in conversation with Alex Christopher Williams.

© Alex Christopher Williams

Roula Seikaly: I understand that Black, Like Paul was your MFA thesis at the University of Hartford. How long were you thinking about the project before starting to work on it?

Alex Christopher Williams: I started making the earliest photographs in this series in 2012. I was an undergrad at that time making pictures of my mother down in Florida. After that project had ended, I moved to photographing my father who lives in Cleveland, OH but the gap just became insurmountable. I didn't want to make pictures of us on Skype, which was an exciting idea back then, so I began making pictures of myself and families that I would meet on the street. I thought of the groups of people I would meet and photograph on the street as families, silhouettes of an ideal community that I was, at least momentarily, a part of.

It was an evolutionary process that I worked on over the course of many years. I returned to pictures of my father at the time that I was thinking about going to graduate school at the University of Hartford, and I used those pictures for my entrance portfolio and told Robert Lyons, the director of the program, that that was the project I wanted to work on for my thesis. It took a long time, from start to finish, to figure out how to exactly voice my ideas with this work.

© Alex Christopher Williams

Seikaly: As I'm looking at Black, Like Paul, the images register as straddling photographic genres: documentary, portraiture, and maybe landscape. And if that's true, what motivated a multi-genre approach to it?

Williams: Yeah. Well, the way that I'm making pictures is a reflection of how I came to the medium and looking at photographers who work in a similar vein. I don't necessarily subscribe to specific genres. I'm more interested in the power of photographs and what they convey individually. And if it's still life or a portrait, then I'm kind of resting on the laurels of the image as opposed to maybe sticking with one genre.

Seikaly: It's an enigmatic image set. I moved through it sequentially, and also opened the book at different points to see what it looked like without following the sequence as laid out in the book, you know what I mean?

Williams: Yeah.

© Alex Christopher Williams

© Alex Christopher Williams

Seikaly: That reinforced the enigmatic-ness, and that viewing or reading experience is satisfying. So, I'm really excited to see what that looks like in the book.

Williams: Well, if I could go further, I was making pictures of my father, and at a certain point, I had to start photographing the gap that was between us, because of where I was living and where he was living. So, I started by making photographs of men in my father's likeness that examined ideas of masculinity and paternity and how we manifest these ideas. I also had to confront the history of tropes and archetypes, not only about masculinity or fatherhood, but also how the Black body is historically represented in images. For a significant amount of time in our country, Black bodies seemed to have an intrinsic relationship to violence in photographs and art and I wanted to, or at least attempt to, break this narrative.

I began making these pictures at the same time when we were talking about Michael Brown and Eric Garner and Tamir Rice, who was shot blocks from where I grew up in Cleveland. I had plenty of reason to be outraged before, but... Tamir hit me in a way that none of the others did because I was doing that same exact thing at his age in some of the same exact neighborhoods as he was. You know, I pass for white so I didn’t look like him when I was his age. I think that's kind of the underlying point to why I was making these pictures in the first place and while I come from a similar ancestral heritage, I never had to face those issues. It made me ask, what really is Black and what is my relationship to this identity.

© Alex Christopher WIlliams

Seikaly: As you've worked on this project and spoken about it, does it get any easier to talk about how you exist in the world? By that I mean, what passing for white affords you?

Williams: Yeah, no. Simply, no. Actually, it has never been. When I was in graduate school, 95% of my peers and mentors, if not more, were white. They didn't have personal experience with these topics and why would they. But, that made it even more difficult for me to work through because I was navigating this space myself. So, finding a community to have a conversation with this is difficult. I should say after showing in a more predominantly Black community here in Atlanta, it's not any easier. The politics of identity is tricky, maybe even more so here in Atlanta.

I was showing the work to a gallerist in New York a couple of years ago who gave me a good perspective on this question that I will never forget. She told me, “quite frankly, you're never gonna win and to just stop trying to have that battle.” I've never asked for permission to be Black. I've never asked for acceptance to be in these spaces. I have simply just said, "This is who I am." And while the work pictures other people, the book and the series is about me and my relationship with my father and my identity... my journey, ultimately.

© Alex Christopher Williams

Seikaly: Has your dad seen the book? If you care to chat about it, and you're not obliged to at all.

Williams: Sure.

Seikaly: What are his thoughts on all of this?

Williams: Yeah, my dad's kind of funny. He's seen the work, of course. I've been photographing him for nine years now at this point. He's a typical Midwestern, hardworking, middle-class, meat and potatoes kind of guy, so he gets to work, but I'll say this, there was a moment where I think it clicked for him when he saw the exhibition of the work here in Atlanta, where somebody had come into the gallery and was commenting on a photograph, and he said very proudly, "That's actually me there. My son made these pictures." And that was really nice, but that's the most I got out of him.

© Alex Christopher Williams

Seikaly: You chose not to include an artist statement or a companion essay in the book. What made that the right choice for you? We talked briefly in our introductory interview, but I'd love to hear more about this.

Williams: Yeah. Well, I'll say this. I've been asked about this a couple of times, and I'll say that I have not spent as much time considering it as other folks have, and I think that is a reflection of my philosophical belief that art is a visual language and that it is communicating, I think, clearly and effectively. So I don't want you to think that I'm trying to skirt around this question 'cause I don't have the answer. I just truly believe that these pictures are telling some of these things for me. And to speak about it didactically in text form, I feel like I would be doing the work a mis-service.

I fully realize the political and sociological moment that this book is coming out in. Our country is in the midst of having really difficult conversations about race and identity, most of which I don't think fully address the nuanced landscape that the conversation should be having, which I feel my book is more aimed at. But I'm not an activist in that way. This book is not commenting on that. This book is about me.

© Alex Christopher WIlliams

Seikaly: Is it important to state that you are not an activist? Is that accurate? Should readers see the book, and you by extension, as the subject and not something to be marshaled for other, broader social concerns?

Williams:: I'm not comfortable saying that I'm not an activist because that makes it seem like I don't have anything invested in that conversation. I do. For example, I'm vegetarian, but I don't preach PETA talking points or burn down buildings to free chimpanzees for the ALF. My personal beliefs are something that I hold dear to me, but, yeah, again, there are people that are better-suited and more prepared for being more authoritative about their activism. I just... I don't think that I am.

© Alex Christopher Williams

Seikaly: Thank you for clarifying that. Going back to your 2018 Der Greif post, you described “being unseen and unheard” in your street photography practice. Do you relate that to being a mixed-race man?

Alex: Oh, yeah. Yeah, it's funny because I think I was talking about making pictures like Garry Winogrand when I said being unseen and unheard, right? But you're right, I live in a predominantly Black community, and folks in my neighborhood aren’t concerned about the theoretical quandary of my ancestral heritage, and whether I am or not in their community.

To many, I'm sure I am just a white boy to them. To others, we keep up with each other and don't get caught up in my racial identity. I'm always looking for dialogues and engagements that are more sincere, and I think that anyone who spends time with me, we quickly get past that. At least with folks who grew up around interracial couples. For folks who grew up in a community like me, with many interracial couples, I'm not that strange.

© Alex Christopher Williams

Seikaly: Does passing as white, in your experience, allow or endow you with that all-consuming male gaze, something that can set up how Black bodies are consumed by a variety of audiences?

Williams: The white male gaze…

Seikaly: Yeah. The gaze that is all-consuming, rampant, unchecked, or voracious?

Williams: To my point I made earlier, thinking about how Black bodies have been represented historically in images is something that I was intentionally navigating how to play with acknowledging this kind of trope, and getting past it. So I did that by making pictures that were very intimate and sincere, genuine and vulnerable. Vulnerability is almost the antithesis to this kind of machismo that we picture gangsters and thugs as. But as far as associating my skin to the way that I'm viewing the boys I photograph, I firmly disagree with the ultimate conclusion. I don't see the boys I'm photographing as an ‘other’. I passionately, and emphatically, see so much of myself in their innocence, confidence, and vulnerability.

© Alex Christopher WIlliams

Seikaly: Sequencing is a crucial part of every photo book. Could you talk about an image or two that shaped the final edit?

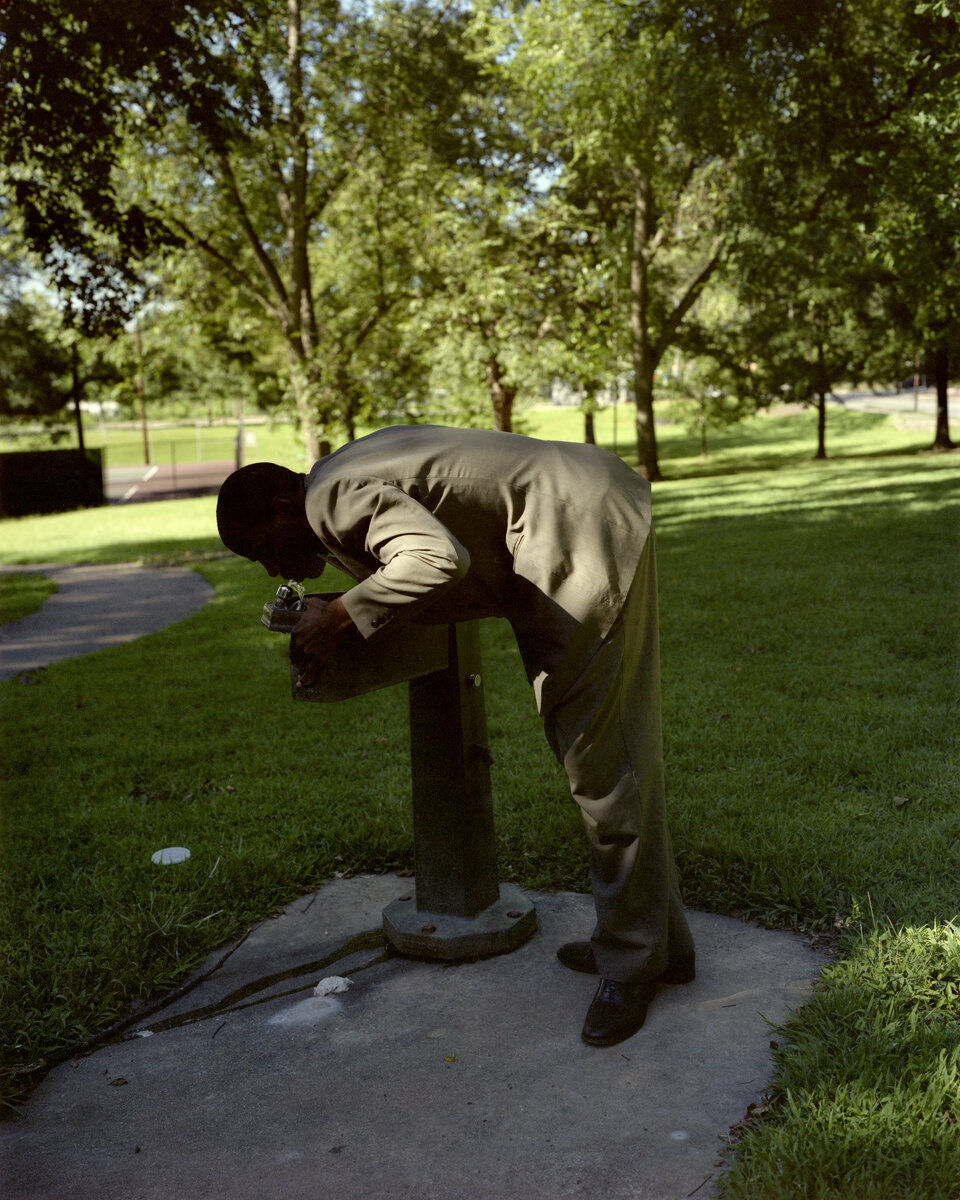

Williams: One of the early pictures I made for the project was of the man in a suit at a water fountain in Atlanta. He told me a story about why he wore a suit and how it was important for him to set a good image for his children. He wanted to teach them to have respect and dignity for themselves and by having respect for themselves, it would demand it from others. So he would wear a suit and take them to school, and then he would go to his construction job and put on his construction clothes, and then when it was time to go pick up his kids, he would put a suit back on and take them home. I saw him as the perfect father figure.

There were so many archetypes that I saw in him. Being at a water fountain in Atlanta, obviously, the symbolism of a water fountain is a very poignant image that harkens back to Jim Crow segregation in the South. When I got the negatives back and I saw that his identity had been skewed into perfect darkness, it allowed me to project any man into his silhouette, and that's what really made that picture so powerful.

In the book, this photograph is in conversation with a picture of one of my neighbors who would frequently come over to the house and ask, "Mr. Alex, can I have a picture? Can we take pictures today?" I saw these pictures as collaborations between us because he was giving himself to this picture, but I was also like, "Why don't you lean this way and why don't you look over here?"

The photograph shows him in hesitation and with a vulnerability, that occurred to me after the fact that he looked like he was being frisked by the police while up against the wall. He was looking down and away in a moment where the fragileness of his youth was looming over him. I sequenced these two pictures together to create a dialogue with the Jim Crow segregation of yesteryear and the recent conversations of policing and state violence in contemporary times.

So, I acknowledge that there are some difficult inherent post-colonial issues that we have to deal with as photographers, but I think that I have approached them emotionally and intellectually with a true, genuine admiration for the people who I'm photographing.

© Alex Christopher Williams

Seikaly: How did you connect with Kris Graves, and what are your thoughts on producing your first book?

Williams: Well, I should start by saying shout-out to Nelson Chan at TIS books who I had a portfolio review with a couple of years ago at Mark Steinmetz and Irina Rozovsky’s space The Humid in Athens, GA. He’s a Hartford alumni so we'd known each other for, I guess, a couple of years at that point. He put me in contact with Kris and we connected when he came down for the Atlanta Celebrates Photography book fair.

To be honest, the way that I envisioned this book, coming out of graduate school, I wanted to make this pristine art object for a book and so a lot of the conversation in producing this was navigating how to make that happen affordably. Kris’s presses focus on producing books that are more affordable than typically priced books and that's absolutely, morally, where I'm at, but with the things that I wanted to do with my book, it just made it incompatible. So I had to spend time really figuring out how I was gonna navigate those challenges, and ultimately, Kris's press was the perfect outlet for it because all the bells and whistles really weren't contributing to the underlying narrative of the work.

Black Like Paul

Seikaly: It sounds like there was quite a bit of restructuring your thought on what's essential to the book, what's not, what must be kept, and what can be jettisoned as far as the production is concerned.

Williams: Yeah, absolutely. And don't let me speak for him, but I believe he's trying to include voices that haven't been included before in the landscape of contemporary photography. And what is the point of doing that if those people can't afford these books?

Seikaly: Absolutely. I've worked on one project with him so far, and it was an honor to work with someone who is so clear-minded and clear-eyed in his aesthetic choices. He's a much-admired colleague, so I love knowing that the two of you worked together on this.

Last question, do you have an ideal or intended audience for this work? And if you do, who is it?

Williams: Well, I've never made work with an audience in mind. I'm most interested in the authentic representation of an artist in their work as possible. So, with that said, I don't have a specific audience in mind nor do I think I ever would. I guess my work is for folks who are interested in nuanced conversations and who are interested in breaking down these monoliths of identities that we're, honestly, still trying to build up within our current political spaces.

Seikaly: Absolutely. Thank you so much for that generosity.