Left: Looking at Marvin, 2014 Right: Looking at Poitier, 2014. © Aaron Turner

For the past seven years, Aaron Turner has been making Black Alchemy. This photographic series and soon-to be-book published by Sleeper Studio uses still life, abstraction, appropriation, and occasional painting to reflect the complex historical representation of Black identity and culture.

Turner constructs sculptures and montages from photographs of historical Black figures, collections of images from Ebony Magazine, and his own family archive and re-photographs them with a 4x5 camera. His images are chaotic and filled with distortion – often as subtle codes intended for viewers to absorb, process, and attempt to decipher. Photographic paper curls, folds, and shimmers with reflection and reams of light and shadow. An image of Frederick Douglass repeats itself throughout the series – at times with softened focus, at others collaged jaggedly.

Many of Turner’s images use figures whose historical significance is important yet lesser-known. For example, “Looking at Drue King, 2018,” creates a folding montage of the 1943 yearbook photo of King, whose membership in the 1941 Harvard Glee Club sparked the desegregation of venues for college musical groups touring the South. Turner reimagines the photo as a three-dimensional object: photocopied, folded, and basked in light and shadow, giving new life to a pivotal, yet underreported figure in the history of desegregation. His process is, in a sense, an abstract shrine.

Other images devolve into full visual hallucination – they can be hard to focus on, know where to look, pulling you in while building on Turner’s interest in historical confusion. Ultimately, Turner’s gaze reforms how we understand history, the role images play in shaping it, the memories we hold to it, and the details we teach each generation forward.

There is a lot to soak through and it gets personal and layered in Turner’s family history.

Here we go:

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Aaron Turner

Seen, 2018. © Aaron Turner

Jon Feinstein: I want to start by discussing your title "Black Alchemy." In some ways, I read its present and future context as a nod to Black renaissance. And rebirth. With a nod to the legacy of Black artists like Kerry James Marshal and Romare Beardon, who you cite in your statement. I'm hovering between literal and metaphoric here...

Aaron Turner: It’s all of those things, in a way. More so, a nod to the legacy of Black artists and Black American history. I recently re-examined myself and tried to figure out why I like to pay homage or honor those who came before me. It goes back to growing up in Arkansas. I vividly remember being in elementary school and having pretty much all black classmates, specifically these very passionate teachers, mostly Black women. There was so much pride in learning Black history, and you were swiftly corrected and made an example of if you did not know who the prominent Black figures in history were. It was the same thing at home in my family, and everyone knew each other too. Some teachers taught various generations of my family; I had the same teachers as my aunts, uncles, parents, cousins, and brothers did. The same level of expectation was everywhere. There was so much tradition within the family structure and outside of it, which never left me. The memory of culture is part of what I am trying to capture in my project Yesterday Once More.

The name “Black Alchemy” comes from that and everything I experienced leading up to graduate school. I was also trying to hint at a speculative space, asking myself: what has happened to lead us where we are now, what does the future look like for humanity? I adapted the idea that art should be speculative early on and that it should consider the future we imagine to exist, but you have to look at the past in the present.

Black Alchemy also suggests metaphors, and the literal aspects of the darkroom, the majority of the project is made with a 4x5 camera. That space is unpredictable, I’m following this particular recipe, but I don’t know how this film will turn out. It’s Black history, black & white film, black material, Black perspectives, Black artists, blackness, race, dark spaces, and unpredictable circumstances.

Looking at Drue King, 2018 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: Do the recent uprisings influence or change how you think about this work and the ideas behind it?

Turner: The recent uprisings don’t change how I think about the work or the ideas behind it. They are making me think about how much of the present to include in the work. But in terms of why I make art, no. If we pay close attention to everything going on, there is a lot of referring back to the past. Whether it’s MLK & Malcolm X, Black Panthers, the institution of Slavery, protest in sports, Jim Crow, segregation, intersectionality, Black feminism, anything else you can think of. I was already putting these things in my work to have conversations about what they mean.

All this stuff happened in the past, and they have actively repeated themselves. One prime example being protest in sports, Kapernick taking a knee was not the first time we dealt with this. What about The Syracuse Eight, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and the NBA, Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics, the Muhammad Ali summit?

We still have to go back to the past and acknowledge these events. If that happened more, maybe society would have a more heightened sense to correct systematic injustices.

Freedom Study #1, 2018 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: What is the personal significance behind the image of JFK, Jesus, and MLK?

Turner: This photograph is a direct nod to familiar commemorative objects present in African American households in the late 1960s and 70s, and even still to this day, most likely. I am sure it existed in other communities' homes or at least some version of it. This photograph is my version of "The Holy Trinity of the Civil Rights Movement" minus Robert F. Kennedy. Also, all three figures in the picture fit the narrative of serving the disenfranchised, which further implicates them as martyrs to a cause.

I did not necessarily see these figures presented in this way growing up, but I would see them individually in certain places. I would see portraits of Jesus at my maternal grandmother's house and my paternal grandfather's house. I'd see memorial photos of MLK at school, the Civil Rights Museum, because I lived near Memphis, TN. One of the main motivators behind this piece was seeing a painting by Kerry James Marshall titled We Mourn Our Loss #1, 1997. There is a whole series of different iterations he did for an exhibition titled Kerry James Marshall: Mementos. I saw these figures all presented in one field of view, and it immediately connected, so I wanted to make my version of that. I did not hear much about Robert F. Kennedy as I was growing up, so he is left out of mine.

These actions are acts of remembrance and acts of faith that push forth specific movements through history. The decorative aspect of a portrait on a wall, a church fan with a historical leader's face on it, and streets renamed to commemorate a person are all devotional acts of commemoration. Specifically, when I think about MLK and Malcolm X, I ask myself, will their names ever be at rest or detached from civic engagement. I am interested in exploring the normalities of their lives moving forward.

History Repeats, 2018 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: I'm drawn to your mix of abstraction, straightforward still life, and images that fall somewhere in between. My takeaway from this is a commentary on the blurring of history, personal narrative, and a kind of telephone game of intergenerational storytelling.

Turner: I'm glad you mention intergenerational storytelling because I am drawing from art history and specific Black abstracts from the 60s & 70s artists. The stakes in art get higher and higher over time and the ability to do work that meaningfully addresses both the narrative of art history and the present moment gets harder and harder to do. One of the positions I take from Kerry James Marshall and apply to my practice is the understanding that the work I make is not important just because I make it. But, that attempts to work towards a more critical position in the historical narrative of art history.

With Black Alchemy, I am looking at and employing abstraction from a particular perspective. As a Black artist. With that being said, there is the past notion that people only wanted to be considered an artist and not a Black artist because the designation of one's self as a Black artist could have a limiting effect on your ability to operate in the mainstream. This idea still exists today, which is why not all but some artists choose abstraction.

Frank Bowling addresses these same notions in an article titled "It's Not Enough to Say 'Black Is Beautiful' (April 1971) by using work by a number of his male colleagues including Melvin Edwards, William T. Williams, Al Loving, Dan Johnson, and Jack Whitten (I'd also like to include a group of female artists to think about: Alma Thomas, Howardena Pindell, Carmen Herrera, Mavis Pusey, and Mildred Thompson). In this particular article, he deals with assumptions around paintings and sculptures made by Black artists, often considering the political implications while ignoring the importance of formal qualities, intent, and their roles as artists. Bowling uses language such as pragmatic, uncluttered, direct, secrecy, disguise, and sneaky while describing a plethora of things on this complex topic. Still, those very terms lead me to dive headfirst into Black Alchemy.

Moves from family archive (#1), 2015 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: I understand that your great grandmother suffered from Alzheimer's. Do you see parallels to memory and abstraction in your process?

Turner: Yea, I was young when my maternal great-grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer's, it affected the way I saw and understood things for a while and still today. One specific thing that became a focus of mine was family heritage, putting together a family tree. My dad and paternal grandfather put together a family tree for both sides of my family, but there were all these missing parts to it once it got to my great grandmothers on both sides of my family. My grandmother's and great grandmother's generation is often very hush on "family secrets" if you want to categorize them as such. Still, the sentiment is that this knowledge is none of your business.

My great grandmother was more forthcoming during phases of her Alzheimer's but still never gave a full account of things, as far as I know. My dad was trying to figure out who her parents were to continue and fully complete the family tree. There was no photographic evidence to go along with this, and not many documents to go along with names. The absence of photographic evidence is why I photograph my family and the region I grew up in under the project titled Yesterday Once More.

Untitled, 2015 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: Why is it important for you that this series is black and white?

Turner: There are a few reasons the work is in black and white. I find color distracting sometimes, and I don't want to discuss it formally concerning the work. Black and white keeps it simple, when the conversation gets to blues and yellows around this specific body of work then for me all the reasons I made it and the conversations I want to have around it go out the window. I want people to focus on what is in front of them and respond accordingly to their understanding.

Black and white is also a metaphor for race and ways of thinking. I also want to focus on specific points in history to call attention to overlooked injustices. I aim to shift the analysis away from or toward the Black artist as subject and emphasize blackness as material, insisting on Blackness as a multiplicity.

Questions for Sol, 2018 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: I'm always fascinated by the role titles play but specifically your decision to alienate between images that are "untitled" and those that use titles as hints or clarifiers. Can you tell me a bit about your thinking here?

Turner: I think all artists struggle with titling, and some artists are particular and utilize titling as a way to control the narrative or intent. I believe some works don't have to be titled, and others need clarification. I am mostly concerned with knowing internally, why I did the work. If I can speak to that when the time comes, that's what matters the most. Sometimes I don't want to lead the viewer. I purposely want to leave room for interpretation. I'm more interested in people's responses or reactions to the work than going in the direction I lead them.

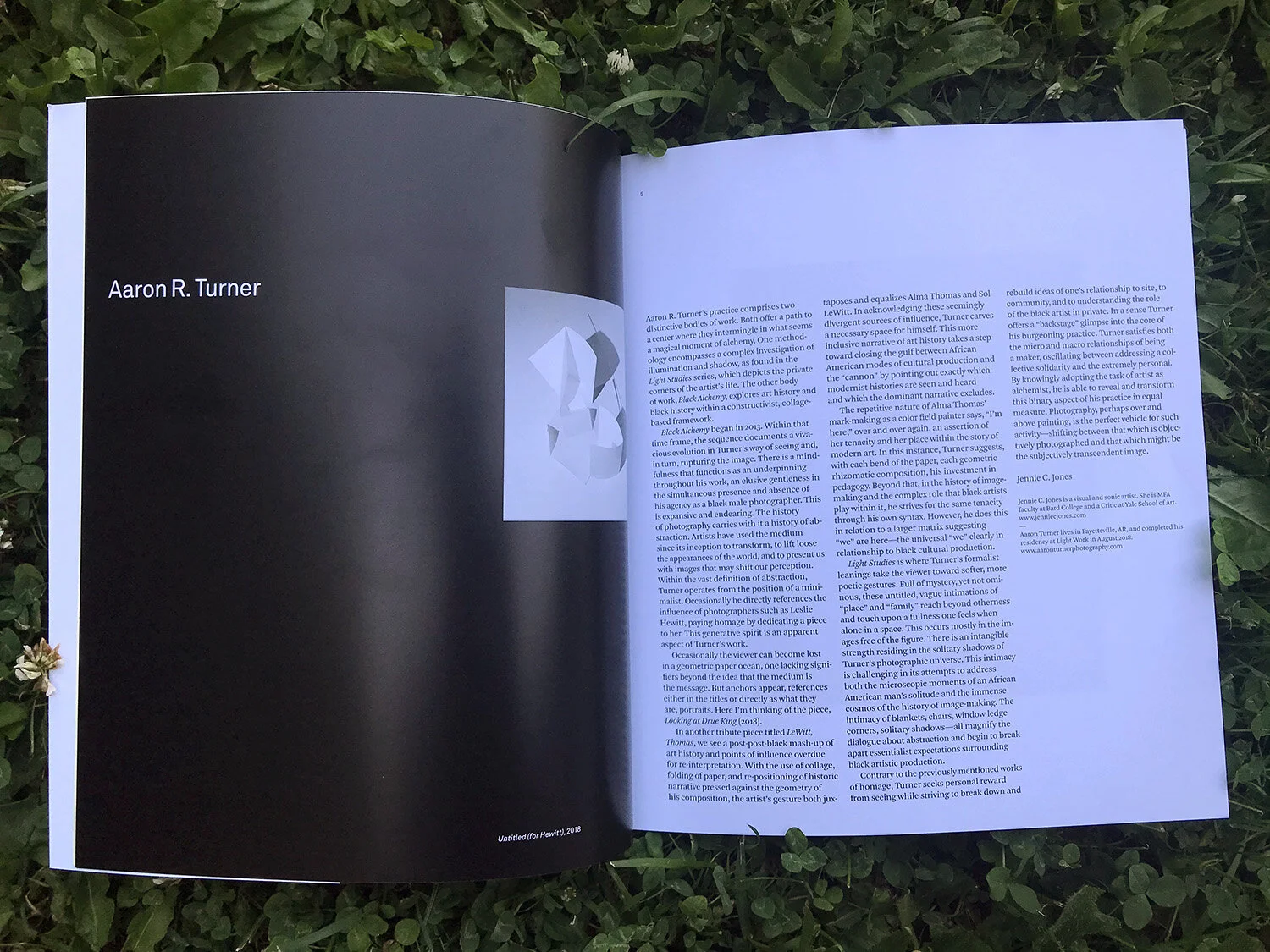

Aaron Turner’s feature (with essay by Jennie C. Jones in Lightwork Contact Sheet #202.

Feinstein: You’ve mentioned Jennie C. Jones' as having an influence on your work....

Turner: Jennie C. Jones is amazing. She wrote about my work for CONTACT SHEET 202, I’ll always be grateful for that. She is also a fellow Mason Gross MFA alum. I can't give an overall definitive statement about the influence Jennie's work has had on me as an artist, except that I really respect her and her studio practice. When I first saw the work, I was drawn to it and felt an understanding of it. It gave me the confidence to move forward boldly with my work because of the boldness she explores minimalism, surface, color, sculpture, seeing, hearing, music, and sound.

My older brother has a saying: "It's important to see people who look like you doing what you do." It was vital for me to see a fellow Black contemporary artist making in a similar fashion that I was interested in working. For me, Jennie’s work really calls attention to her role as an artist, and consistent esthetic in repetition which challenges the legacy of geometric abstraction and minimalist form.

The former or the latter, 2018 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: Black Alchemy started in 2013, and you have it organized into "chapters" on your website. What, aside from time, for you, marks these distinctions?

Turner: Time is an essential factor in the different volumes of the work. The time points to growth in understanding and perspective. Before this pandemic, I was an everyday studio person, now I don't have access to it, for the time being. I say that to emphasize that I take long periods between work, I go to the studio, but most times, I'm thinking and reading, not making. I make art in really long or short bursts, and then I sit with it for as long as I need to. I do a lot of work but never show it all. Each volume points towards a specificity.

In the first volume, the underlying concern is the metaphor between racial passing and abstraction. In volume two, I'm more focused on commemoration and specific abstract artists. Volume three uses the previous Black Alchemy photographs as an archive to make new juxtapositions, but also, it's exploring more speculative aesthetics.

Malcolm and Martin (Patterns for Binion #1), 2016 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: Has editing and sequencing your work for your upcoming book impacted how you think about it/ its personal and conceptual frameworks?

Turner: Yes, it has. I've always felt that all of my projects are connected because of why I make it, but this is emphasizing that. As I am writing and organizing the work, more personal narratives come to the surface that has nothing to do with how the work looks or the title but more so to do with me as a person and specific experiences—a lot of self-reflection.

Untitled (self), 2015 © Aaron Turner

Feinstein: This work is abstract and personal – in some ways filled with codes to explore and decipher. Given that it will be a book, set for a level of wider “consumption,” what do you hope a wider public gleans from it?

Turner: Great question Jon, this is something I've been thinking about. It's the thing I consider the most when doing the work. It's my perspective first, my lexicon, but I intentionally intend to have multiple entry points in my work. The various entry points are essential often with this thought of I won't be present with the work, so like you said these codes, I leave little clues in the forms, composition, and titles occasionally. One of the things I'm doing with the writing for the book is to peel back the layers of my motivations, because they go beyond the conversation of art, and draw more from life experience. I feel writing more from this perspective and level of intentionality and detail will genuinely open the work to the broader public.

Editors note: Aaron is also the founder of Photographers of Color, an important project you should know about. Read more about it in his interview with Shades Collective here.)