Dese’Rae & Felicidad with their children Theo and Gus, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Philadelphia based photographer Helen Maurene Cooper uses the 19th-century wet plate collodion process to make socially distant Ambrotype street portraits of her neighbors during quarantine

Helen Maurene Cooper’s photography is driven by personal connection and relationship building. In long-form documentary projects, she has photographed drag queen culture, Floridian mermaid performers, and has collaborated on portraits with Black and Latinx-owned specialty nail businesses on Chicago’s West Side. Feminism, entrepreneurship, and the power of adornment are central to her work.

Cooper moved from Chicago to Philadelphia’s East Kensington in 2019. Months later, as Covid 19 swept the nation, the challenge of engaging a new creative community and balancing parenthood (Cooper has an 11-month old daughter) and professional demands intensified. How does a photographer who relies on the intimacy of portraiture navigate these limitations? How does one get to know their neighbors when all interactions must take place at a mandatory six-foot distance, our faces obscured by masks?

Cooper takes this challenge in stride. Setting up her 8x10 camera just beyond her front door, she commits her neighbors’ images to history on wet collodion plates. People of the Pandemic, River Wards - Philadelphia is a project for the Covid age, calling to mind the visual traces of historical crises including the Civil War and the 1918 influenza epidemic that tested American resolve.

We spoke about producing a mature body of work that reflects seven years of working with the collodion process, social distance portrait photography, how connections are made amidst pandemic, and how the white gaze might shape this moment of social reckoning.

Roula Seikaly in conversation with Helen Maurene Cooper

Franchesca and her daughter Victoria, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Roula Seikaly: Why start a new project in the middle of a global health crisis?

Helen Maurene Cooper: I began this new work, it seems in the way I begin all my projects: trying to make sense of a nugget of an idea or to work through a technical problem, or an aesthetic glimmer that turns me on. In this case, I was preparing for Zoom teaching in my home studio and, at the same time, looking at my 8x10 camera. I’ve messed around with the camera somewhat awkwardly, but never really spent the time or had an idea that would inspire me to scale up from and develop my skill and confidence with the 4x5 format.

And a few afternoons later, I was sitting on the front steps with my young daughter when a woman walked by with a super cute dog. Something about self-isolating in the pandemic makes it easier to bring personal interaction to public space. Whitney and I struck up a conversation, and the more we chatted, the more I wanted to get to know her. Photography has always been a tool that I use for social engagement. At this point in my life, interactions lead to portrait making. I just really wanted to photograph her. And I thought why not photograph my neighbors? Why not photograph my neighborhood of E. Kensington at this time?

The first two shoots I did were from inside my front door with the neighbor masked standing on the sidewalk. I soon learned that I needed to move outside of the studio onto the sidewalk to have the help of the sun. After a few sessions, I realized I was on to something. I started looking for portrait references, including work by Judith Joy Ross and Dawoud Bey, to inform and deepen the project images.

Tommy, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Seikaly: Who are you photographing, and how do your collaborations begin?

Cooper: Portraits are an excuse to make a connection to another person outside of my home, but from a safe distance. It is an opportunity to build something for the future. I reached out to artists in Philly who knew lived in the neighborhood, but didn’t know personally. Through those early sessions, neighbors introduced themselves and asked to participate. On sunny days, I set up my camera and a light or two just outside of my studio. People drive by and ask what I am up to. I give them my Instagram handle while we're talking, have them look at the work and then ask that they follow me. If I am interested in their look, I then message them with a video of the process and set up a time.

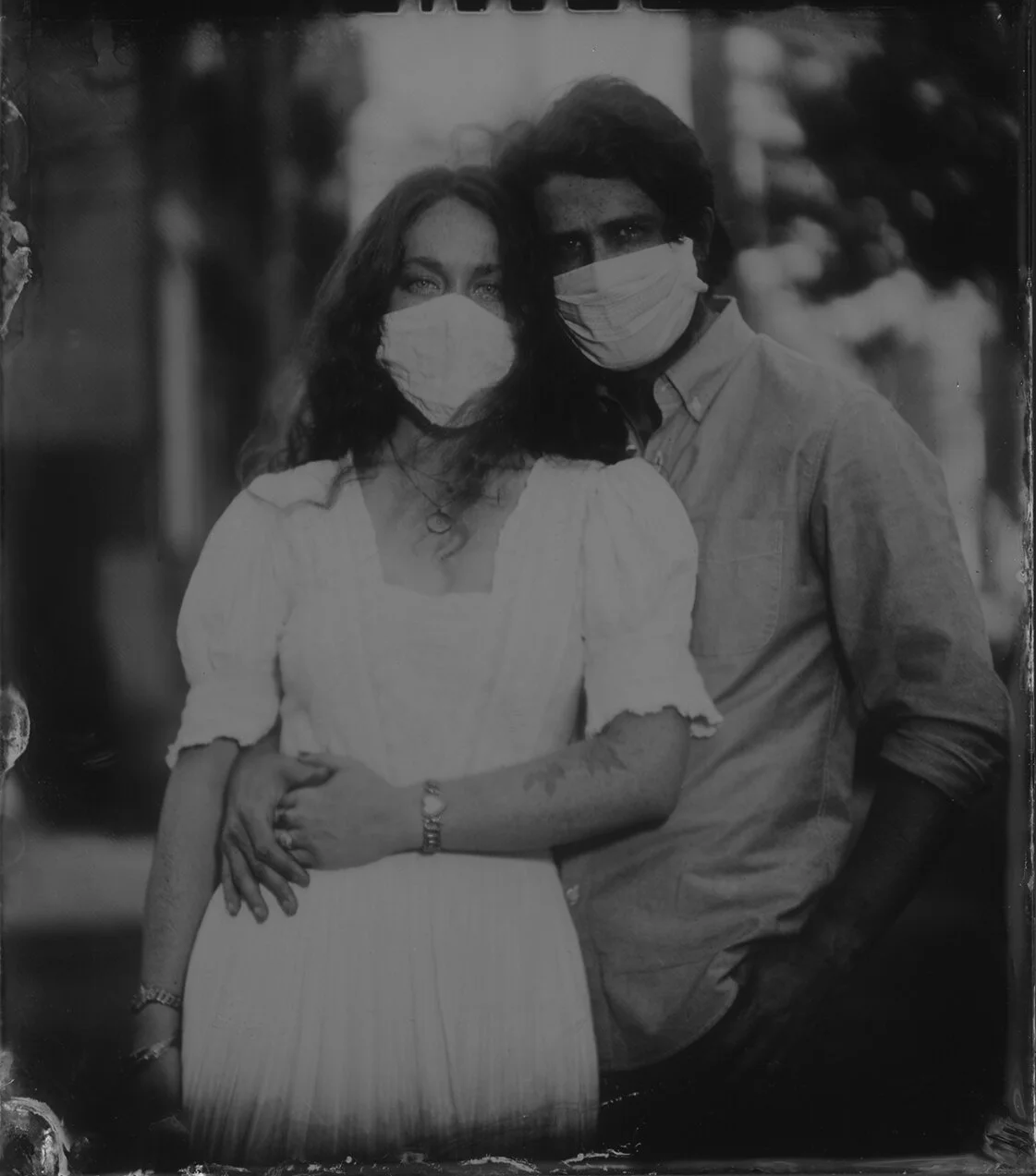

Laura and Shane, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Seikaly: Why is the wet plate collodion process appropriate for this series?

Cooper: The 8x10 is somewhat of a spectacle. Philly people are nosey and they want to know what you're up to. The wet plate process is important to my image-making during the pandemic because it demands a time commitment from a sitter and produces visible results within minutes. Most people have never seen the process and the novelty holds their attention. There is also a morbid romance that collodion brings to a portrait of a person wearing a mask in 2020. Some of the older people I’ve photographed have mentioned that masks in photographs harken back to the Spanish Flu. But, I think of the American Civil War, and the parallels of mass death and trauma that we are experiencing as a society. After all, Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner were making wet plate photographs.

Helen Maurene Cooper setting up a portrait

Seikaly: Portraiture is an intimate process that can involve contact between sitter and photographer. How is collaborating with your subjects affected by social distancing? How is your creative process on the whole affected by these safety mandates?

Cooper: Safety first! Everyone wears a mask and I never position people or get closer than 8 feet.

As I mentioned, most of my sitters have seen the camera on their daily walks around E. Kensington. I have followed up via Instagram, and they are familiar with the process and output. Sometimes, I send my sitters examples of poses I would like to try, other times I work more intuitively. In many cases, I am working with children, and their attention span is a factor. I can get three plates done (approximately 35-45 minutes) with one to two-second exposures before I lose their attention. I try to make the secession fun. Occasionally, I get the shot in one plate but often, for one reason or another, we reshoot. It's the first time in my artist life that I feel that I have the time to work with the same people until I get it right.

The pandemic poses so much danger and risk, and yet, my process and practice are thriving under these conditions. People are aching to connect and families are looking to entertain their children. They want mementos of this deeply scarring time. One of the women I photographed said she had always wanted a collodion photograph of her family, but never dreamed it would happen during a pandemic. Another couple I photographed were supposed to have a wedding in June. They are using the image we made to send as a postponement notification.

Sarah and Nicole with their Children Noa and Elliot, 2020 © Helen Maurene Cooper

Meredith, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Seikaly: How does this project fit into your creative arc? What would you like to see become of it in the long run?

Cooper: My recent work, Blue Angels, is a series of 4x5 ambrotype portraits made in collaboration with drag performers and gender-based performance artists. The work harks back to a real but imagined nineteenth-century queer history. I started the project while I was still living in Chicago, and continued working on it in Philadelphia. I did a short residency last summer in south Florida at the Storefront Art Studio, a space run by dear friends Jill Weisberg and Brian Gefen. I wanted to expand Blue Angles to another city and community before I gave birth.

I was six months pregnant and nervous about the dangers wet plate chemistry could pose to the baby. Through the generous support of the Marguerite Bierman Scholarship at Kutztown University, I was able to get the required funding to train a former student, Bethany Riley, in the collodion process and to take her with me on the residency. Without that support, I wouldn’t have felt comfortable going to Miami to make portraits with drag kings and queens. And it was imperative to me to make another chunk of work in the project before becoming a mother. I didn’t get into the studio in the postpartum period. I really didn’t want to be separated from my baby. Becoming a mother shifted my focus. I don’t have time or the desire to go out to clubs and see people perform and to follow up with appointments. Blue Angels is on hiatus at the moment.

Carmon, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Seikaly: How did you land on this work?

Cooper: For months, my mind has been going round and round about what to make. I landed on these 8x10 COVID portraits of my neighborhood. I tend to make photographs in complicated places. These portraits are no exception. E. Kensington was, at one time, Philly’s industrial heart. But, moving factories overseas, poverty, and drugs gutted the area. We are now in the second phase of gentrification, with a massive new construction boom. My neighbors are working-class Irish people who have lived in the same homes for generations; artists who bought property fifteen years ago and are now white-collar professionals.

I photograph hetronormative and queer families, single parents, lovers, and partners equally. I am thinking a lot about family these days. There is so much being written about how COVID is affecting the work-life balance of heterosexual women… that at home many families are still living 1960s gender roles. Photographing family units at this time is important because of the tension in how couples manage child care and how they do it in isolation. What does it mean to be a parent? What does it mean to be a partner? I know I’ll continue to shoot until the weather grows cold, and think about how to exhibit or publish this project.

Korin & Keiko with their child Eukiah and future baby © Helen Maurene Cooper

Seikaly: As a white woman, do you think about the concept of ‘white gaze’ as you approach and ultimately work with sitters from other cultures?

Cooper: The question of the ‘white gaze’ is something I’ve been thinking about since my grad school days (almost 15 years ago) at School of the Art Institute of Chicago. It was often brought up in critiques to address the responsibility of a white image-maker. I think a critical question should always be, “is this work being made because this person or these people are a certain race, or does it relate to a larger structural or social issue that a photographer is investigating?” In my case, I am mesmerized by the aesthetics of hyper-femininity. This is what led me to photograph mermaids, nail artists, and drag queens. My approach to subjects is collaborative. I want them to like how they look, and I work to achieve those ends.

In the current project, I show the sitter each plate I shoot. I expose the plate, I go into my darkroom, develop, stop, and then fix the plate. I bring the plate onto the sidewalk and show the sitter. We discuss the image. I have no interest in making a picture that the sitter hates. I direct the posting and make suggestions for edits on the next plate, but I ask for feedback and if the sitter wants to try something different, we go in that direction.

I will always be a white woman with a graduate degree. In that, there is a power imbalance. There is a privilege that I wear with my skin color. It doesn't mean that my life is easy, but my life isn’t hard because of the color of my skin. If I get pulled over by the police for a moving violation, I am likely not going to end up in a jail cell and die “mysteriously” like Sandra Bland. I try hard in my life and my art practice to be conscious of the imbalance of white privilege and also the privilege of class. This doesn’t mean that I don’t mess up or sometimes say the wrong thing... because sometimes I do.

Caroline, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Cecilia and Venny with their children Eugene and Zella, 2020. © Helen Maurene Cooper

Seikaly: I first reached out a few months ago about the new work, and now want to ask how you and your family are holding up? Many quarantines have started and ended, and COVID cases are spiking throughout the nation. How are you doing 6+ months into the pandemic?

Cooper: Over the last few months the project has evolved dramatically. The wet plate process is particular. My bad habits with cleaning the glass and pouring plates intensified when I scaled up to 8x10. I reconnected with my collodion teacher France Scully Osterman for what I thought was a small technical problem, and we methodically reworked every problem that was present in the work. Zoom has been a super helpful tool for this. In some cases, I have asked to watch France do the process in her studio, and in others, she watches me do a particular task in my darkroom.

Cleaning the glass fastidiously is imperative. Pouring a clean and even plate, minding that the collodion doesn't drip and that the pour bottle is small enough to handle, ensuring that the puddle in the middle of the plate is big enough, rocking the plate ever so slightly to touch each corner... there are so many more details. I don't come by this kind of technical precision naturally, but I am driven to make work that reflects my effort to learn. And then there is the issue of learning to see the light. With Blue Angels, the light was fabricated and easier to control. Learning to see the sun is different, looking for full shade and knowing when to add a little flash to fill.

Time management is a huge issue in this work. For every hour I spend shooting, I spend at least one hour preparing and two hours cleaning up. The chemistry is toxic and my studio is dangerous, so I can't have my daughter anywhere near it. My partner is doing a major and necessary time-sensitive renovation on our home, and my mother helps with the baby so that I can make work during the week and my sister has been helping me on the weekend. Cleaning up one day’s shoot and preparation for the next often falls to the end of the day, once the baby is asleep.