The Chinese board game Go, invented over 2,500 years ago, is an abstract strategy game in which two players vie to occupy more territory than their opponent. Using black and white stones, players take turns grabbing up empty spaces on the board, trying to fill as much space as possible or knock each other off by surrounding each other’s stones on all sides. It’s also the basis for artists Ina Jang and Brea Souders – a collaborative duo working under the name “Coramu” – latest exhibition, curated by Yael Eban at Tiger Strikes Asteroid Gallery in Bushwick, NY.

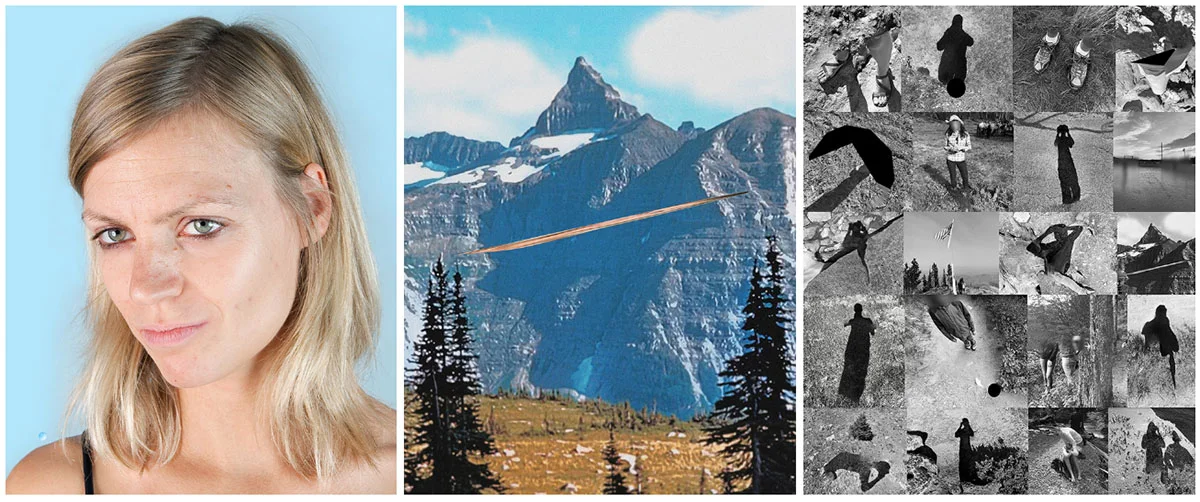

Souders and Jang use the structure of the game to create a competitive photographic dialogue. Images, all printed at the same size, are exhibited in two competing parallel lines stretching around the gallery’s perimeter. While the majority of the images are in ultra-saturated color, each row corresponds to the competing “black” and “white” pieces of the game, and range from wildly abstract to mountainous landscapes, commercially-lit portraits and still lifes of cigarette packages. It’s not always clear whose photos are whose, but the competition to surround and overtake is a constant.

Brea, Jang (aka Coramu) and I corresponded to discuss everything from board games and photo collaborations to the splintering evolution of “post-photography.”

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Brea Souders and Ina Jang.

Jon Feinstein: How did this collaboration come about? What's behind the name Coramu

Coramu: It came together naturally. We have known each other since our first encounter at the Hyères Festival in 2012. A few years ago, we had a chance to get together again, and then we quickly started exploring the possibilities of working together. We joke and laugh a lot when we meet, so it helped us to move along with some of the bizarre ideas that we would have never tried on our own. We chose the name Coramu because we thought it sounded like an effervescent beer.

Feinstein: The exhibition title and many of its themes are an homage to the Chinese board game “Go.” Where are you both in this? How did this become a jumping-off point for you?

Coramu: As Coramu, we were already working on multiple projects by the time we discussed the idea of “Go”. We both had vague memories of playing Go as children, and were inspired by the game for its simple rules, complex outcomes and visual appeal with the black and white stones. A year before we first formed Coramu, AlphaGo (a computer program) had recently won a series of Go matches, in competition against the Korean professional player Lee Sedol. We simply wanted to play a game like that, but in the form of photography.

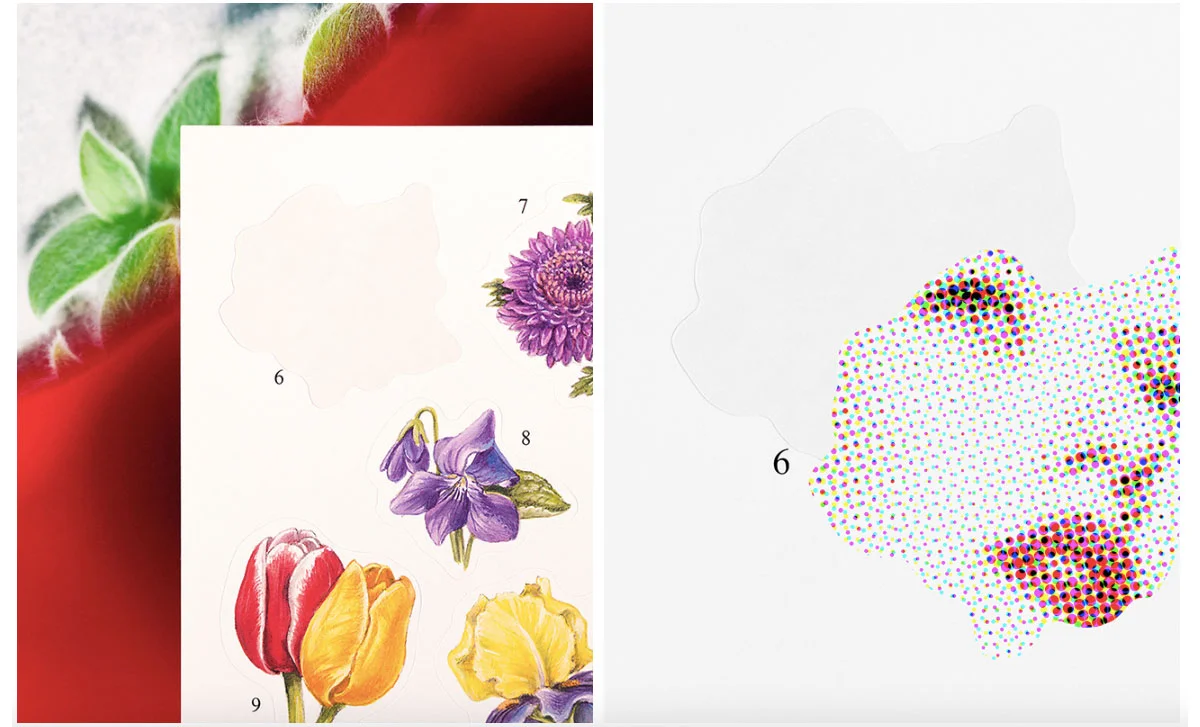

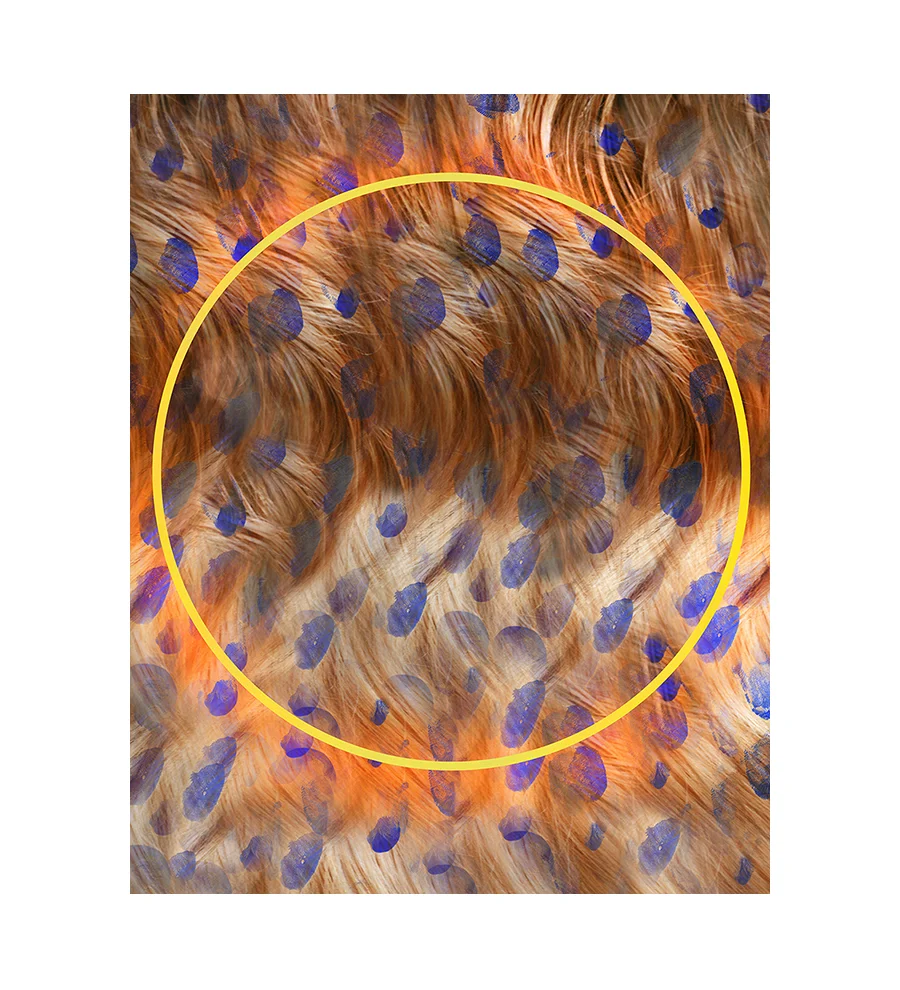

Our game is loosely based on the board game - we borrowed the idea of using black and white stones, which translated in our game to black and white templates. The black and white templates were exchanged simultaneously and with each subsequent move, we must alter the image while still incorporating a part of the image we were given. The black and white sequences run together simultaneously. Much like the board game, our game of Go is political, strategic and territorial yet respectful of each other at the same time.

Feinstein: Can you elaborate on your thinking regarding Roland Barthes' ideas about photography as death and resurrection?

Coramu: The goal of the game is to move on from the existing image upon exchange, and to create something new that brings a part of the previous image along. As our exchanges accumulate, the preceding ‘turns’ become part of a bygone era within the game. So with each turn you will witness something that existed but has died alongside a kind of resurrection in the form of a new image. Sometimes we revive elements from images made much earlier in the game. This then creates a new segment in the chain that incorporates a memory from an earlier time. These new fragments take on the quality of an apparition.

Feinstein: I'm interested in the stacked linear presentation. Why is this important to the work and viewing experience?

Coramu: It’s a good way to aid viewers in understanding the concept of the project. You are able to walk through the images chronologically, and you can also see the exchanges happening simultaneously on the top and the bottom. Every time we exchange our files, we put the new images in a row with the previous ones to see the gradual - and sometimes aggressive - changes. As a result, time appears to speed up and slow down throughout the game. Sometimes the exchanges reveal a surprising synchronicity in our thinking. We wanted visitors to experience something similar. They are like parallel film strips. It’s effortless yet enthralling to experience the work in this presentation.

Feinstein: This seems to build on / go into the next chapter of the "post-photography" discussion of a few years back, which itself was in many ways a resurrection of ideas (appropriation, death of the author, impossibility of “truth” etc) that made headway in the late 1970s and early 80s. How do you feel it's expanding upon, or breaking that conversation?

Coramu: There is a high level of appropriation inherent in the game, as each image must be incorporated somehow into the subsequent one. It shows how a single image can morph over a lifetime and it raises questions about authorship, intent and truth in today’s digital landscape.

While truth in photography is slippery, the project does document our reactions to the world today and incorporates materials, images and technologies from this time and the recent past. We always exchange our images as digital files, rather than printed photographs. There are no rules as to how we make our next move - it can be made with a camera, in Photoshop, with a scanner, with a phone, painted or sculpted and then photographed, etc. This format allows us to pull in images and materials from the news, advertising, fashion, the street, nature and our own archives and then blend it in with our imaginations.

The “post-photography” conversation is really secondary in this work - it’s a natural result of the game’s format. The game is diaristic and quite personal - it documents our evolving friendship, the ups and downs of our lives, location, weather, holidays, shared humor and our responses to a rapidly-changing world. We learn about one another through the project and the game grows with this expanded knowledge. It tells a shared story over time.

Feinstein: What's it been like working with curator Yael Eban? Has her curation etc influenced how you think about the work and ideas behind it?

Coramu: It’s been fantastic working with Yael. She recently joined Tiger Strikes Asteroid as a member and was preparing to curate her first show with the New York gallery. A very small run of our project had been published in book form by FujiFilm to coincide with our participation in the Unseen Fair in Amsterdam last year. After viewing the book, Yael proposed that we show the project at Tiger Strikes Asteroid (TSA). TSA is a non-profit, artist-run space and she emphasized that she’d like us to work in a site-specific way and explore unconventional displays.

Yael is also an artist and was able to approach our project both as an artist and a curator. She brought the printing material to our attention - it has an adhesive backing and can be wrapped around corners. It was the perfect medium for our project - it allowed us to display each sequence in a seamless way that references a film strip and internet scroll.

Feinstein: There seems to be a lot of interest in photographic volleying and collaboration over the past few years (Ben Alper and Nat Ward’s A New Nothing, Mia Fineman’s “Talking Pictures” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among others.) Why do you think that is and what's drawn you to work this way?

Coramu: It’s a time of rapid change and people are wanting to band together in the face of uncertainty. It seems like the right time to try new things and to have more conversations. And recent technology has made that easier.

It's also an organic response to the world evolving around image-based social media platforms like instagram and snapchat. We scroll through endless streams of images from all over the world everyday. We put stickers and filters on photographs to alter them instantly with a few taps on the screen. We are programmed to ’feel’ more connected in the digital world, and that feeling of intimacy encourages us to make a more tangible connection.

It feels great to make something with another person and put it out there. Musicians have been working this way forever...why not visual artists?

Feinstein: Does this exhibition mark any change, significant point or chapter in your collaboration? I know that "what’s next” is one of the most annoying questions you can ask in an interview, but, “what’s next?”

Coramu: This is the first installment of GO. We plan to continue the game throughout our lives as it will only get more interesting as time goes by. We’re excited to see how the sequences evolve alongside changes in our lives, technology and world events. Leading up to the opening, our recent exchanges were invigorating and fast-moving. We want to welcome this momentum.