© Aneta Bartos

The artist’s latest exhibition gives an unexpected look into family dynamics and the nature of aging.

New York City-based Aneta Bartos’ adolescence in Poland was shaped around her dad's bodybuilding career. Starting at age thirteen, she'd often travel alongside to assist him with various competitions, sometimes competing herself. Into her adulthood, she continued visiting him every summer, and in 2013, he asked her to make a few portraits of him to capture his physique "at his best" before his body began to deteriorate. While these were initially photos of him alone, they evolved into a collaborative, father-daughter series about the dynamics of their relationship.

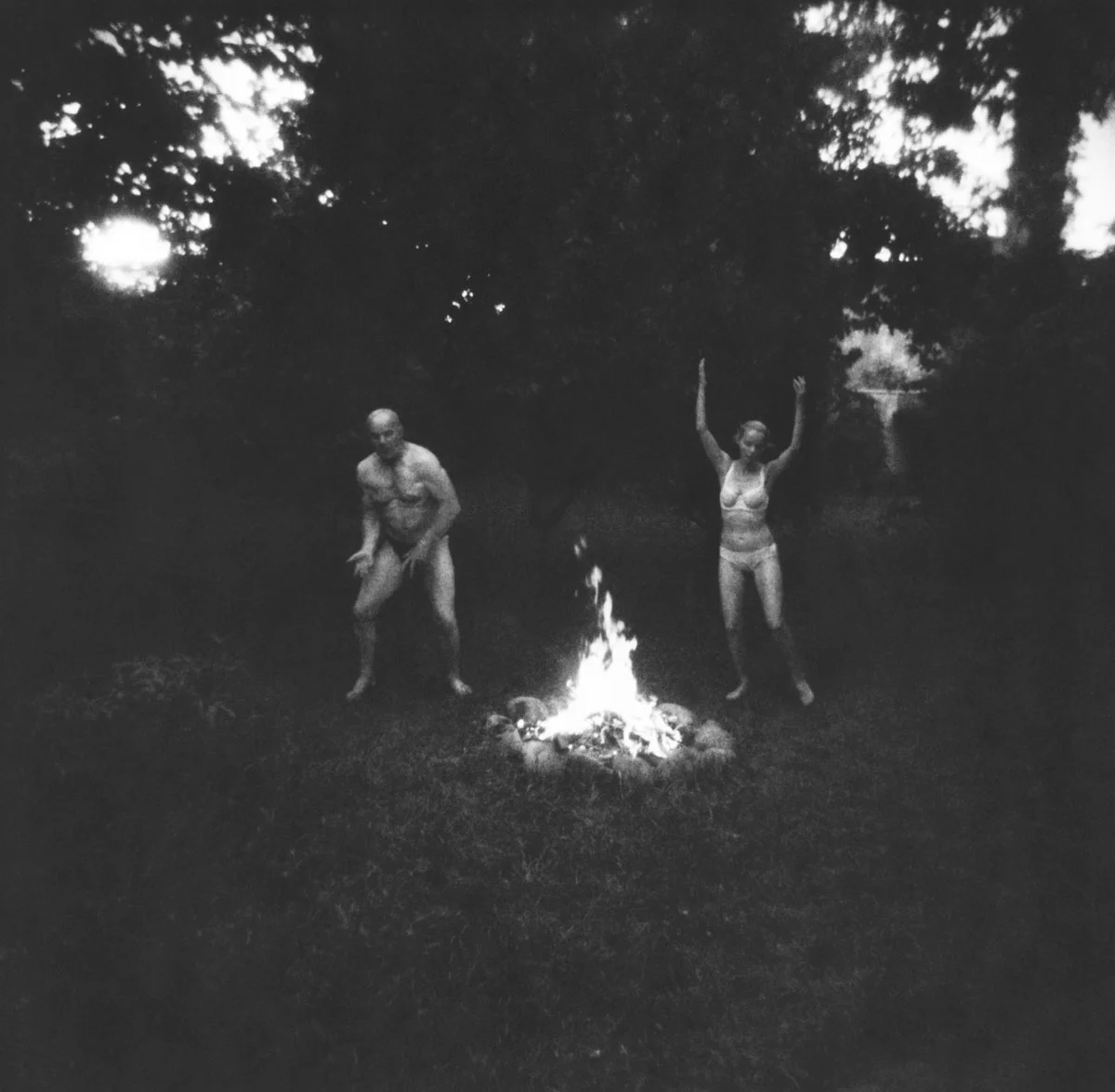

Bartos' latest exhibition, Family Portrait 2015-2018, on view at Tommy Simoens Gallery in Antwerp through May 25th depict the artist with her retired bodybuilder dad, often in their underwear or bathing suits. Their mix of scenarios range from getting ice cream and playing on the beach to performing various behaviors of emotional comfort for the camera. In some images they stare into the lens, engaging directly with viewers, while in others, they seem to act out, recreate, or be entranced by memories from Bartos’ childhood. While the various states of undress might make some viewers uncomfortable, a deeper look reveals a tender, thoughtful window into family bonds and the fragility of life itself.

I emailed with Bartos to learn more about the series and her family dynamics.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Aneta Bartos

© Aneta Bartos

Jon Feinstein: This series began as you documenting your dad at a time in his life when he wanted to preserve his physique -- before his body began to deteriorate from age. At what point (and why) did you decide you wanted to turn it into a collaborative self-portrait project?

Aneta Bartos: After shooting my dad alone for three summers, I felt I needed to introduce a new element to the project or end it all together. I decided to jump into the frame with him and see what happened. It seemed like a natural progression. I wanted to dive deeper into father-daughter relationship surpassing the perspective of a younger child who was idealizing her powerful and loving father. Family Portrait explores the relationship more closely, digging into a dreamscape of memories, reenacting fleeting moments and alluding to the joy, rebellion and complexity inherent when the daughter grows up and comes of age. It also explores the intricacies and challenges facing a powerful aging man and human.

Did making these photos change how you think about your relationship with your father?

It hasn’t changed our relationship, however, it has made me more aware of how narcissistic he can be about his body, and what a huge part of his existence it has played.

© Aneta Bartos

Feinstein: Has it changed how you think about portraiture/self-portraiture/photography as representation?

No. I don’t really find myself thinking about these things.

Feinstein: Growing up, you were raised in an environment in which your parents were pretty open about nudity and the body. Has making these photos - in which you and your dad are fairly "uncovered" - changed your ideas about the body?

Bartos: Working with my dad on this project felt very natural and we were at total ease with each other, due to the fact that body was never a taboo in our household. It was in fact in stark contrast with our culture, which has a very puritanical way of perceiving bodies. I think it reveals the close-mindedness of our perception and how simplistic and negative our thoughts are about something as natural as the body. I feel these perceptions only pollute our senses, resulting in fear, aggression, and ultimately hate in our society.

Feinstein: Why the decision to include the weightlifting equipment etc. in the exhibition?

Bartos: When the gallery and I first started discussing the possibility of an exhibition, it became very clear to me that they were not interested in a traditional photography show. They liked the fact that I had just shot a video work, which adds a new layer to series and expands into another medium. I was also asked to think about ideas for an installation and within a day I proposed transporting my dad's vintage weightlifting equipment from the gym he founded in Poland, which dates all the way back from the time I was a child. Visiting his gym as an adult feels like walking into a time capsule.

It represents his livelihood, decades of shaping his body, and taking part in international competitions, which gave him a lot of satisfaction and stamina. Today, as he has aged, it has become a burden. It is something he claims he doesn’t want anymore, doesn’t really use nor makes any money from, and takes up all his time. Yet, he is unable to let go, and move into new ventures that he once dreamed of doing after he retired.

© Aneta Bartos

© Aneta Bartos

Feinstein: How do you think that changes or influences how viewers engage with the photos?

Bartos: I think inclusion of the very tactile equipment gives a show an extra dimension and engages the viewer even further by being able to see, touch and smell the original objects that have been such a huge part of his life. There is a poignancy in them. They are who my dad was, a big part of the challenges he now wrestles with, and the reason I started photographing him the first place.

As a part of the installation I also chose to paint one of the walls with the colors and patterned paint roller I remembered from growing up in my grandmother’s house (with my dad) in Poland. This wall acts as a transition from one of the main gallery rooms into a small, dark, and ambient viewing room for the video, complete with green velvet sofas.

Feinstein: This was your first solo exhibition in Antwerp, and you mentioned that it's going to be in Japan in the next year, you've exhibited the photos in other countries, and it's been widely written about.. Do you think different audiences or different cultures respond to it differently?

I definitely think different cultures have a diverse mix of reflections based on how they grew up and what was being taught in their society. When I showed the project for the first time at Spring/Break Art Show in New York, I had many responses that varied from admiration, to confusion, accusations, and even anger. I remember that people from France for example told me that they grew up in a very similar environment, where walking around half-naked in the house was just typical and they didn’t find that part of the project shocking or controversial.

I also had a psychiatrist visiting the room and stating that she doesn’t see incest in these photos. I thought, damn, you have to take years of schooling to make this conclusion? However, I do enjoy different reactions. It’s fascinating to me and never boring.

© Aneta Bartos

Feinstein: There's a subdued, faded, almost nostalgic color palette and quality of light in all of these photos that feels very intentional (and appears in your earlier work as well). What draws you to this and why do you think it's important to this series?

Bartos: I have been using mostly Polaroid film before starting Dad project. I simply love the aesthetics it gives that you mention above. However, I decided to experiment with something other than a Polaroid that would give relatively similar feeling.

I discovered Kodak Instamatic cameras with working film cartridges on eBay. They had a quality of 70’s family photo album, which fit perfectly with my concept of recreating my memories.

As the project continued and I was unable to find the original Instamatic film anymore, I went back to using original Polaroids, which have been on their last breath due to the fact that any you can find have expired twelve years ago.

© Aneta Bartos

Feinstein: Tell me about the video component- “It Doesn’t Taste As It Used To.” Is this the first time you're using video?

Bartos: Yes. I found it quite challenging to have to learn new medium at the time I was shooting. It Doesn’t Taste As It Used To is about the cycle of life and partially based on an ancient theory that the universe is governed by elements: earth, air, water and fire. The elements are all connected and interchangeable with each other, meaning that they never die. There is a hierarchy where earth is the most material and primitive and fire has a form in the earth plane as well in spiritual realms. During ancient times, the eternal soul’s quest was to eventually become pure fire, which, in modern times can be interpreted as reaching enlightenment.

Ever since my dad turned 70, aging has become a very sensitive and morbid subject. The strongman has begun to be confronted with growing fragility. His realization that he is losing mastery of his body along with seeing signs of the deterioration of his functions have made him fearful for the first time. He is facing the fact that he is on his final path of his journey and contemplating his choices he has made though out his life. He is finding himself unable to take pleasure out of things he used to enjoy.

© Aneta Bartos

© Aneta Bartos

Feinstein: So much of this seems to be about his processing of mortality. How are you processing it?

Bartos: Since there is great darkness and religious dogma about the notion of death, we become paralyzed. We often surrender to these fears, which enable us to experience the darkest parts of our nature. This stops our growth as spiritual beings and puts us in a cell of our own limited thinking. Although I have become more aware of these challenges, I have found comfort in mysticism and spiritually where the lines between life and death are often blurred. I want to celebrate the earth, and all the forces and transitions, including material death that cannot be defined physically, chemically or scientifically.

Feinstein: You've been making these pictures for more than 6 years now. Is it "done"?

Bartos: I am certainly not shooting him this summer and instead moving on to a different project. Since my dad's decline in health and changes in his physique, I can tell he no longer enjoys posing. Over the period of 6 years the project has shifted from immortality to mortality, and it has became a metaphor of a dying world and old order my dad is part of. Even with all the comfort I am trying to find in nature and spirituality, I am still having trouble seeing him age which also makes me more aware of my own mortality. For right now I don’t want to continue the project, but that doesn’t mean I may not be drawn back to it again in the future.