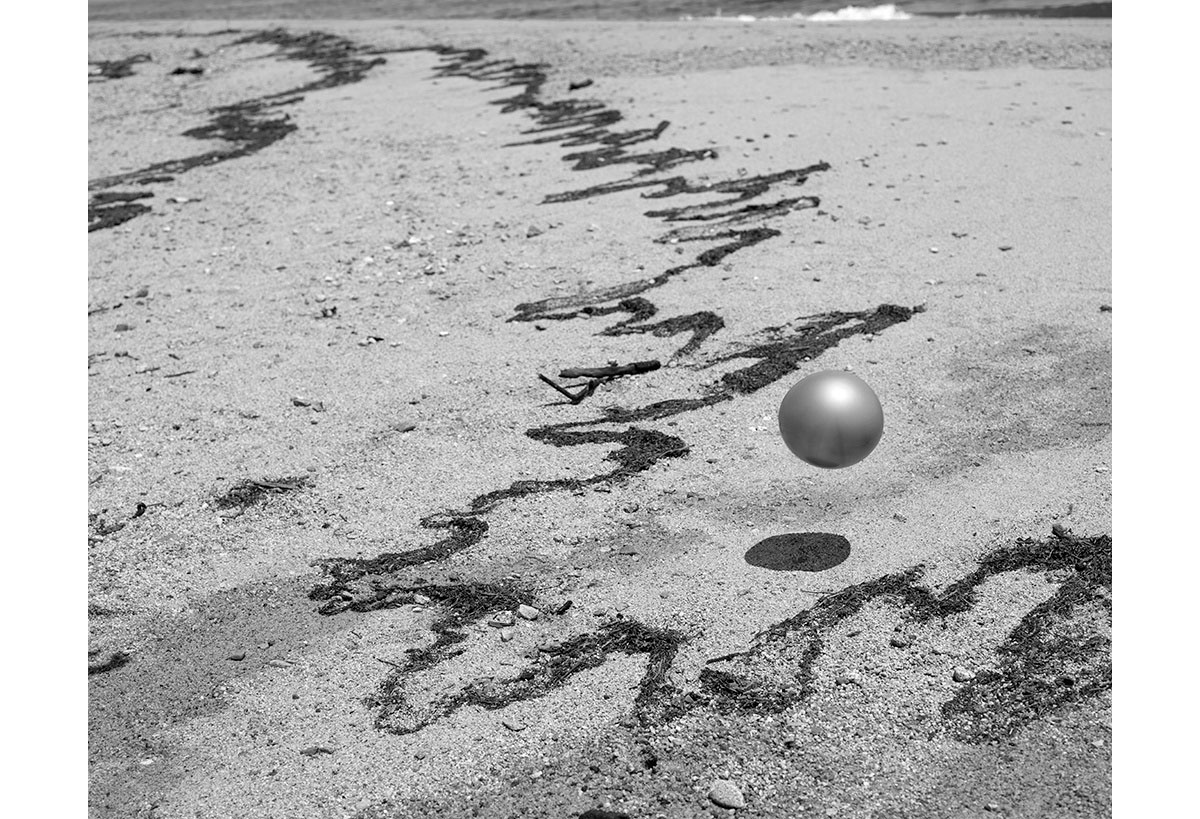

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

Daniel W. Coburn's photographs confront the tension between the artist's inner narrative what's projected to the outside world

Daniel W. Coburn’s Becoming a Specter, on view at Philadelphia’s Print Center through August 4th, is purposefully restrictive and subtle. The artist demonstrates how the elimination of color in a photograph can make the deepest blacks and brightest whites – and everything in between – so vivid and tactile that you don’t miss color at all. And that's exactly what Becoming a Specter does.

The exhibition consists of twelve untitled photographs, four to a wall, in an alcove gallery space on the second floor. Predominantly images of people, they all seem to deliberately capture the split-second moment where nothing looks particularly real as if the subject and photographer have come together on an inhalation.

Exhibition review by Deborah Krieger

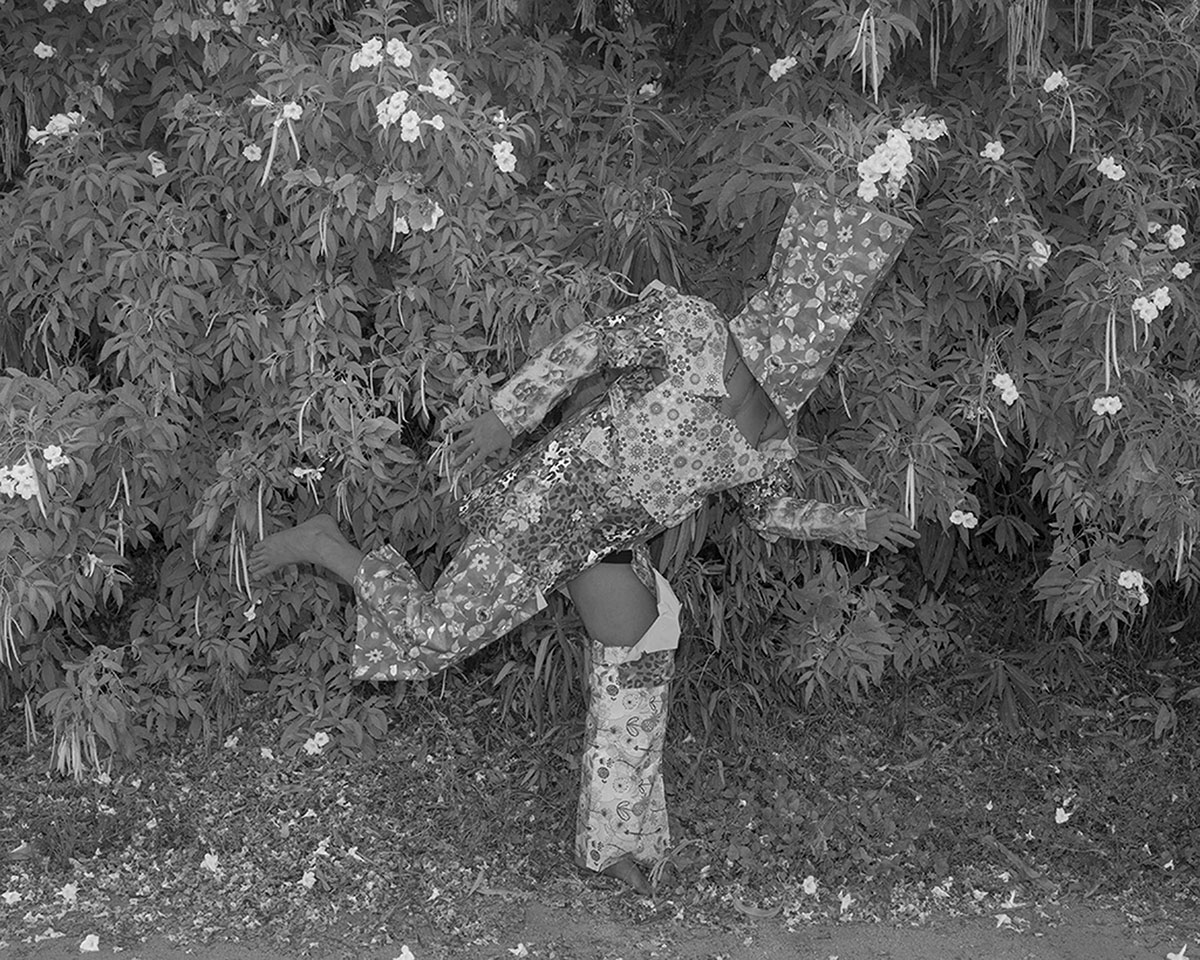

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

One immediate standout is a photograph of a ball caught mid-bounce on a sandy ground, its shadow perfectly circular and separated enough to feel almost disconnected entirely. Dark and light passages mingle over the planes of bodies in motion or in repose, glancing off or diving into textured surfaces, half-concealed by shade or in direct view of the lens. While the images are each individual discrete compositions, presenting twelve of them together lets them volley in matching rhythms of form and shape.

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

My initial impulse is to ask why this configuration of twelve images has been chosen, and why each work has been placed next to its neighbor. In some cases, the formal similarities and echoes in the different photographs make themselves obvious. On the center wall, for example, the two middle photographs’ use of light as a dynamic diagonal compositional element align beautifully: in the Caravaggesque photo on the left, a half-obscured figure lies on a bed as a stream of light filters from top to bottom, slanting right to left, while in the image on the right, that same angle of descent is mirrored by a cloud of flour (or sugar) being thrown in a dimly-lit kitchen. The result is the passing of a profound spiritual moment (a la Caravaggio) from the first photograph into the ordinary setting of a kitchen in its neighbor.

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

Similarly, the two photographs that occupy the left corner of the space—the fourth work on the left wall, and the first work on the center wall—play off one another perfectly, albeit in a different way. The work on the second wall is technically magnificent: a female nude lies on her stomach on a patch of bright sand, shaded by a palm frond, the seam of which lines up perfectly with her spine. And on the other side of the corner is a mirror image of the light-dark-light tonal shifts, where a male figure – presumably Coburn – is captured halfway submerged into a dark body of water. As he breaks the surface of the water in the center of the composition, the image seems to glitter. The placement of these two works on opposite sides of a corner is particularly effective. The recession of the corner (and the line it produces) acts as an inflection point, making the flip from light-to-dark follow logically and simply.

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

The works on the right wall are more closely linked than the other two groupings in the exhibition—they all feature human subjects—and differ from the previous eight works in that they give off an air of being posed rather than candid. Either by virtue of how differently each human subject is treated or because they seem so obviously staged, these four images make the viewer increasingly aware of the photographer’s presence just behind the lens.

Courtesy of The Print Center, Philadelphia

Courtesy of The Print Center, Philadelphia

Courtesy of The Print Center, Philadelphia

A woman’s face is viewed in close-up, her eyes closed in an extension of trust to the person with the camera; a figure costumed in elaborate garb poses precariously on one leg, proving the existence of the photographer by the mere contrived nature of their body language; a woman standing on a beach seems to hold an orb of light, looking directly at the photographer; a nude figure half-hides behind a curtain as if preparing to make a quick getaway through the window, leaving the naked lower half of their body visible.

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

© Daniel W. Coburn, Untitled, work from “Becoming a Specter”, 2018, Archival pigment prints, 16” x 20”, Edition of 12, The Print Center, Philadelphia

In the case of the latter work, there’s an uncanny interplay of who’s watching, and who is being watched: the nakedness of the figure would seem to make the photographer—and by extension the viewer—the voyeur, but the shifty pose of the figure in the image, as well as how they appear to be concealing themselves behind a curtain, as if preparing to watch, complicates the interaction.