© Robert Wade, California, 1969-1970, courtesy of the photographer, from "All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party," PCNW 2018

Seattle exhibition traces the visual descendants of the Black Panther party

All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party, organized by Michelle Dunn Marsh at Seattle's Photographic Center Northwest – as well as an abridged (expanded) version at AIPAD earlier this spring – is an exhibition drawn from a book of the same name and showcases a select group of contemporary black artists, whose work has been informed or influenced by The Black Panther Party. Timed to the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Seattle chapter – the first outside of California – the exhibition looks to how the Panthers' visual codes and social platforms play out in contemporary African American photography. I spoke with curator Michelle Dunn Marsh to learn more about the book, exhibition and plans to take the Panther's legacy into the future. The exhibition is up at PCNW through June 10th, 2018.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Michelle Dunn Marsh

© Endia Beal, Sabrina and Katrina, 2015, from "Am I What You're Looking For?", courtesy of the artist, from "All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party," PCNW 2018

Jon Feinstein: Tell me about the project's origins – how did it get started and where are you personally in all of it?

Michelle Dunn Marsh: In 2006, through my position with Aperture West, I developed some public programming around Stephen Shames' Black Panthers book, which was published to time with the Party's 40th anniversary. In preparation, I visited Oakland, met with Billy X Jennings, an archivist of the Party's history, and met with Bobby Seale, who drove me around Oakland while telling me his lived experiences. As you can imagine it was a powerful moment. In 2008 Stephen's Aperture exhibition came to Seattle. I did additional programming and met members of the Seattle chapter. I kept in contact with Aaron Dixon, Captain of the Seattle chapter, and have learned a lot from him and from [family friend and King County Councilmember] Larry Gossett.

I knew very little about the Panthers before that first trip to Oakland—my friend from Bard College, Roger Scotland, was a history major and was able to give me a brief context for the Panthers among other movements and organizations active after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. After the Oakland and Seattle reunions, I began reading whatever books I could find related to the movement. I responded to how they were using their rights as Americans to enfranchize themselves.

Feinstein: To my knowledge, All Power grew out of a 2016 book bearing the same title, which originally complemented Rene de Guzman's exhibition and now, as I understand, has taken on a form of its own. How do you think the book, original exhibition, and the two exhibitions (AIPAD vs PCNW) you've curated so far function differently, and/or work in tandem with each other?

Dunn Marsh: Great question. Rene de Guzman's exhibition Black Panthers at 50 at the Oakland Museum was phenomenal—that museum is at the epicentre of the Panthers' formation, and because it is not exclusively an art museum they had pieces of buildings that used to be in Oakland, public ordinances, etc. along with photographs by Carrie Mae Weems, installations by Hank Willis Thomas and Sadie Barnette, and more. That our book (All Power was co-edited with Negarra A. Kudumu) sat alongside that amazing exhibition was very humbling.

The book came out through Minor Matters (you know our model), so there was an audience with a vested interest. Gail Gibson here in Seattle said 'are you going to do a show? There should be a show of this.' I was absolutely emotionally exhausted from doing the book—we launched it in July 2016 and had books in Oakland for the October 2016 opening — so I couldn't imagine anything further in that moment.

And then, time passes and you recover. I knew PCNW would do something related to the 50th anniversary of the Seattle chapter in 2018 we are located in what historically was the Central District (though now would be considered part of the Capitol Hill neighbourhood); in a rare move for me I proposed doing a show from the book which has a national, contemporary roster (but was potentially a conflict of interest) or doing something else (not a conflict) that would just focus on the local chapter. The board approved pursuing a show from the book given that the research had been done already.

In the end, I am glad we went this direction as the Northwest African American Museum has an exhibit including many historical photographs, so we can complement that.

Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, "Wait! Wait! Don't Shoot! (An Incantation for Trayvon and Jazz), print iteration, 2018. Installation photograph © Lilly Everett

Feinstein: How about AIPAD? Was the exhibition received any differently in the context of an art fair?

Dunn Marsh: As far as AIPAD vs. PCNW—that was a vast space, this is a highly intimate one. That held a kind of gravitas both in the design of the fair itself and in being AIPAD, one of the longest-running photography art fairs in the world. PCNW is an educational institution and a regional resource that is constantly pushing beyond our spatial and financial limitations to foster new experiences with photography.

In observing viewers there are similarities in both venues—some people come in and are taken aback that they are not just seeing historical photographs. Others spend time with the work but are unsure how it relates to what they may know about the Panthers. And then there are, in the words of Shawn Theodore who exclaimed this at AIPAD, those who "walk in and just feel safe here."

I have taken a calculated risk to present work with the tools for a mainstream audience to learn more, without doing the work for them, while maintaining an integrity for those who understand their own histories and who don't often enough see those histories or narratives presented.

In showcasing ~20 Black artists of multiple generations part of the effort is to offer that there are powerful messages within works that speak to a present the viewer may not share. The viewer may have to learn more to access that aspect of the piece. I think this has been uncomfortable for some people. And that is okay.

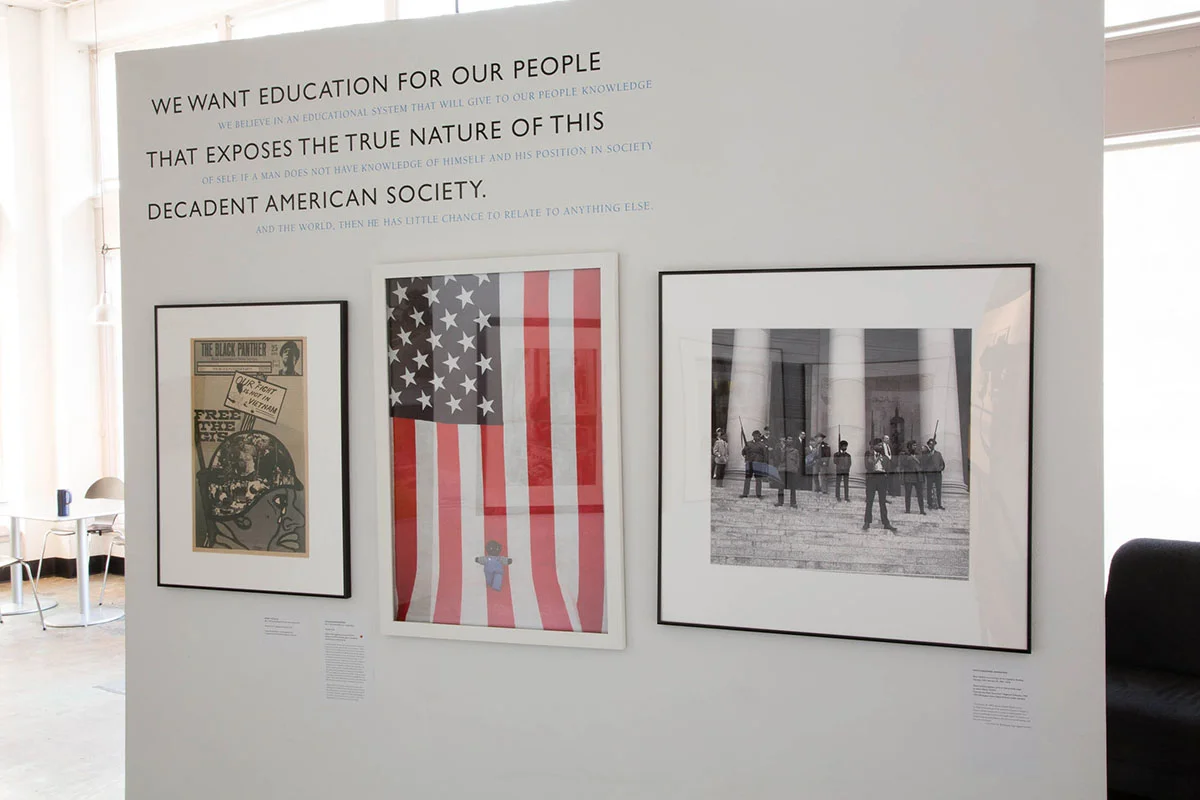

Left to right: works by Emory Douglas, Ouida Bryson, and an historical image by an unknown photographer. Installation photograph © Lilly Everett

Feinstein: What misconceptions or popular informational gaps about the Black Panthers do you hope this clarifies?

Dunn Marsh: To be honest, Jon, I don't hope that it clarifies anything—I hope the exhibition, and the book, complicate. Complicate assumptions, expectations, complicate history and present so that we can be uncomfortable for a while in order to arrive at a better future.

While this exhibition is getting international press and attention, there were plenty of snide comments in my presence about it being at AIPAD. I wore a sari for the opening and many people I know didn't recognize me because of that choice. I have not spent a lot of time talking about racial issues within the beautiful bubble of photography, but plenty of prejudices and assumptions are there, and given the broader tensions within the United States I can't just process that internally anymore. We have a lot of work to do culturally to make space for more viewpoints within the American experience. I'm following Gandhi's exhortation to 'be the change."

© Ayana Jackson, Leapfrog series: Martha, 2016, courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Seattle, from "All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party," PCNW 2018

Feinstein: The crux of the All Power is a look at Black Power and struggle not just historically, but (as I understand it) as something very real, urgent, and moving forward.

Can you talk about the importance of keeping it flowing?

Dunn Marsh: In a continuation of the above, the Panthers were not about Black Power as much as they were about economic power—"All Power to the People." If you read the 10-Point Platform within the exhibition or the book it's about fundamental rights. They partnered with the Young Lords, the Brown Berets, AIM (the American Indian Movement) as well as many Caucasian supporters to achieve their goals. Fred Hampton, in building the Rainbow Coalition beginning in Chicago, brought together disparate groups on the grounds of economic development and improvement. There's a lot to be learned from that today, as the middle class disappears.

The one major element that has become more visible to me in developing the exhibition from the book is the spirit of youth, and the backdrop of the powerful voices from Parkland are of course assisting me in coming to that realization. The Panthers were a youth movement, though historically they are never described as such. The vast majority were under the age of 25—many under the age of 21.

© Kris Graves, The Murder of Eric Garner, Staten Island, New York, 2016, from the series “A Bleak Reality”, courtesy of the artist, from "All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party," PCNW 2018

Feinstein: I'm interested in your selection process for Kris Graves' work, some of my favorite in the exhibition. Over the past few years, he's made two series that could be considered relevant to the legacy: A Bleak Reality and The Testament Project. In your mind, why was A Bleak Reality a better fit for All Power?

Dunn Marsh: Two reasons—one, much of the work in the book is portrait-based, so presenting landscapes created a visual balance. Two, the very direct and powerful series A Bleak Reality which is also easily accessible if you've read the captions but less so if you haven't, hadn't gotten as much attention as Testament. I wanted to shed light on it.

I still doubt that most viewers will imagine the experience for Kris, as a black man, going to the sites where these men have been killed, at the time of day, taking in the ambiance and environment around him, and then holding that moment in a photograph. I find them nearly impossible to look at when I consider that element. And I am very glad they are within the exhibition.

© Kris Graves, The Murder of Philando Castile, MINNESOTA (9:10 P.M.), 2016, from the series “A Bleak Reality”, courtesy of the artist, from "All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party," PCNW 2018

Feinstein: Do you have future plans for All Power?

Dunn Marsh: There are public programs in May and June— on June 9th, there will be a panel looking at the local impact of the Party, both at the Frye Art Museum and coordinated by Negarra as a complement to the exhibition.

We've had some inquiries about traveling the show and have one venue that is a strong possibility after we close, so we're discussing with the artists now.

For me, I will be spending some more time on the 10-Point Platform to better understand how I am supporting the achievement of those very relevant and important goals for all of us.

© Lewis Watts, Graffiti, West Oakland, 1993, courtesy of the photographer, from "All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party," PCNW 2018

Installation photo © Lilly Everett

© Bruce Bennett, Center 4, Bronzeville, Chicago, 2013, courtesy of the photographer, from "All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party," PCNW 2018