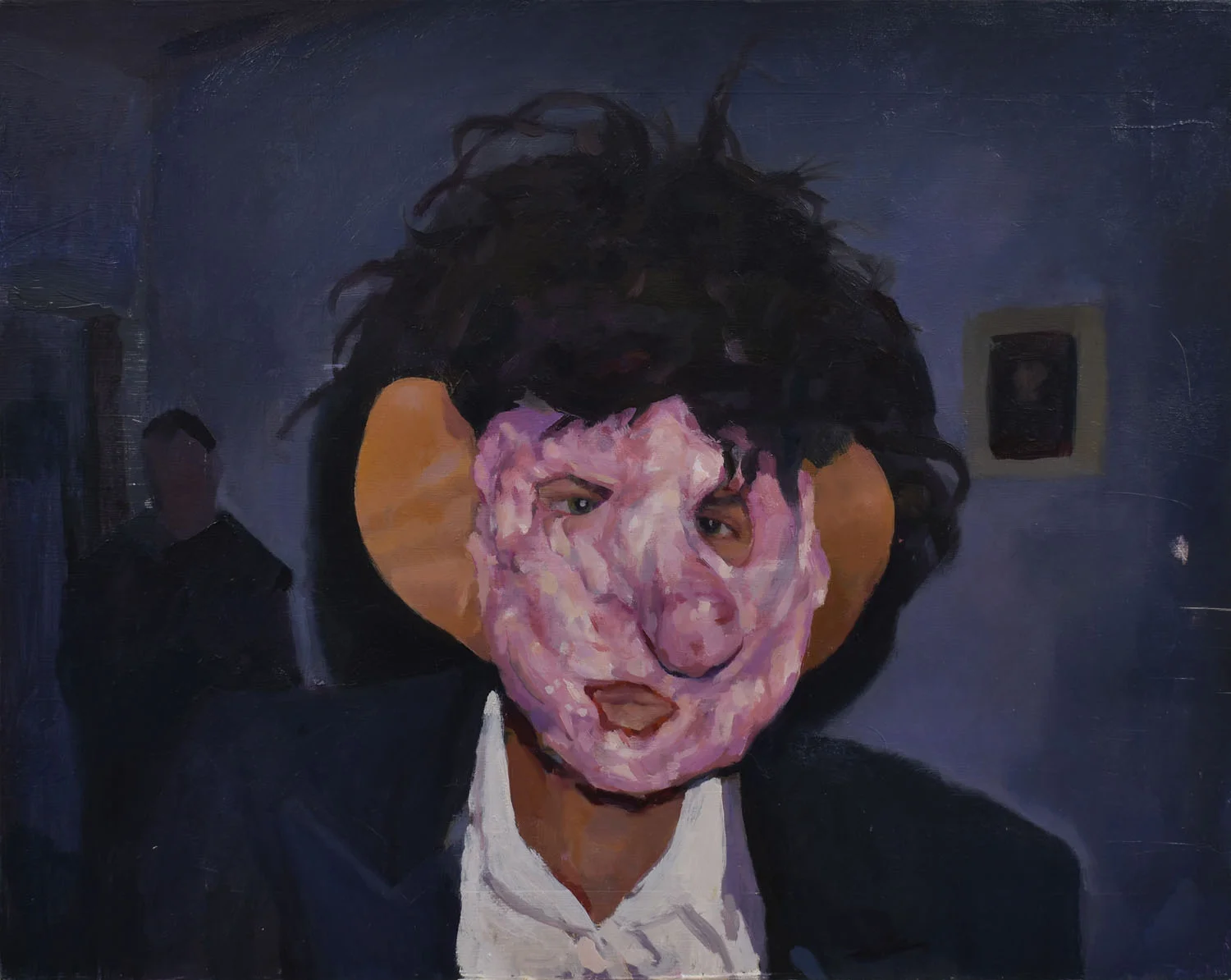

Bernice, 2018. 30" x 36" oil on panel. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Snapshot collector Robert E. Jackson speaks with snapshot painter Justin Duffus about his work and inspirations.

Justin Duffus makes paintings from twentieth-century snapshots and snippets of Americana, highlighting the strange, humorous, often lonely, and sometimes inconsequential moments of everyday life.

In one painting, a boy sits at the edge of a motel swimming pool – shivering with arms crossed – swathed in cyan and blue tones. In another, three business-suited men in a nondescript room walk in a circle around another man, wrapping him in pastel streamers like a human maypole while two women watch. In other paintings, masked figures confront the viewer head-on, the harsh light of a cheap camera flash rendered with jarring elegance. Hung together, Duffus’ paintings embolden a mysterious, open-ended narrative, giving new energy to images with an anonymous or discarded past.

While his sources vary, some of them are based on images acquired from the collection of Robert E. Jackson, the Seattle-based vernacular collector-extraordinaire, whose collection currently boasts more than 12,000 American snapshots from the past century. Like Duffus’ paintings, many of Jackson’s snapshots have a similar attention to the peculiar, absurd or unintentionally artful. Following Duffus’ recent exhibition, Fear of Drowning at Seattle’s Linda Hodges Gallery, we asked Jackson – who is also a collector of his work – to speak with the artist about his practice and the ideas behind it.

Maypole, 2018. 68" x 72" oil on canvas. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Robert E. Jackson: A lot of the content in your paintings comes from being inspired by snapshots. What elements within a photograph attract you and what elements do you reject?

Justin Duffus: I’m mostly attracted to images that suggest a familiar scene, yet somehow the content is ambiguous or unclear. Those images allow me to ask more questions and create space for me to add to the image. Similarly, if the image says too much, I will paint some of it out. Color, too, is a big draw for me. I’m interested in the colors that older film created—those colors capture a feeling different than contemporary or professional photography.

Laguna Hills, 2018. 36" x 36" Oil on canvas. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Self Portrait (age 7), 2018. 24" x 18" oil on panel. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Jackson: What role do photos from your own life play in the creative process of making a painting? In other words, how autobiographical are your paintings?

Duffus: In my most recent shows, about 85% of the photographs I worked from were found, with a few taken from life. But in the process of painting the photos, they become personal to me. By paying such close attention to the details of the subjects’ lives, I realize what attracted me to the images in a deeper way. Spending so much time with them, the paintings can’t help but become autobiographical. The woman in “Bernice” (header image for thie interview) wears a mask and she began to remind me of my grandmother because she was reserved and could be hard to talk to.

Photos I’ve painted from my own life – for example, “Self portrait (age 7)” – are a personal reflection on my upbringing. It was normal for me to play with guns and pretend to shoot my neighbors. I also painted a portrait of my wife in her favorite leopard coat and titled it “Breadwinner.” Phrases like “Who wears the pants in your house” came to mind. In both images, I was asking questions about the roles I’ve occupied in my life, the malleability of those roles and expectations in relationships.

Breadwinner, 2018. 24' x 24" oil on panel. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Jackson: How does the size of the canvas being used inform how you will approach the painting of a subject?

Duffus: It’s the other way around for me, usually. The image typically dictates the size of the canvas. I want the small paintings to feel big and the big paintings to feel intimate. I like when the viewer has to get close to my paintings, but in “Maypole” intimacy is achieved by the figures being almost life-sized, so that the viewer almost feels they are in the room with the figures.

Jackson: In painting from another source like a photo, for example, is your goal to replicate exactly what is seen in the photo or is it a jumping off point for the painting’s content?

Duffus: Mark making always ends up being the main force of my paintings. Sometimes this means the images are distorted and sometimes they look more faithful to the photo, but how the paint meets the surface is always the most important to me. The painting’s relationship to the source material becomes secondary.

The Kiss, 2017. 12" x 12" oil on panel. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Evalyn, 2017. 36" x 40" oil on canvas. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Jackson: Can you clarify and elaborate on what you mean by "mark making?"

Duffus: Yes, ultimately “mark making” is the way paint is left on the surface. There is an unlimited amount of options for how to apply, manipulate and remove dry and wet paint. I am interested in surprising myself in the way I make marks and balance the different qualities which paint contains. In “Evalyn,” for example, the chair in the foreground was painted several times, yet always felt too heavy in the composition. I kept pulling the wall color above the chair down through the chair, painting it out completely. Then that space would feel too empty. The final image contains this history of abandoned attempts and the chair is seen more as an idea than a permanent object.

Jackson: The show which recently closed was called "Fear of Drowning" and the associated images accompanying this interview were from that show. Can you speak to what the title of the show means and how they relate to the paintings?

Duffus: This is where I could easily say too much. I was thinking a lot about our fear of death or the unknown, and about excess, and how those feelings are confronted and ignored. Some of them use water imagery, which is more obvious: “Baptism” and “Poolside.” “Bernice” is a painting of someone completely flooded in her material surroundings to the point that she becomes a thing to fear. The painting “Maypole” attempts to symbolize the feeling of being surrounded by those who are in control. The older men are manipulating and restricting the younger man with streamers as they cover him up.

Baptism, 2018. 48" x 50" oil on linen © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Poolside, 2018. 24" x 24" oil on panel. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Jackson: Can you tell me more about your process – from selecting a snapshot to finishing a painting?

Duffus: Once I have obtained a snapshot, it sits around my studio, sometimes for almost a year. I begin to remember the image when it’s out of my sight and imagine how I want to paint it while I’m on a walk or at my day job. I use a projector or a grid to enlarge the image and get a quick drawing and then it’s ready for paint. Every painting has a life of its own; they all begin and end differently. I vary the amount of attention given to different parts of the painting, trying to find a balance. A face can be painted in a day or in several attempts over a long period of time. I like to vary how I apply the paint and what I do with it after it’s on the surface as well. I use brushes, palette knives, rags, sponges, squeegees, and razor blades to move the paint to a place it can stay.

Justin Duffus in his studio

Jackson: How do you know when a painting is finished?

Duffus: I almost never know. At some point, I feel less anxious around the painting, and it can sit in my studio without asking for attention. I usually ask my wife!

Jackson: How has your painting technique evolved and where do you see your work going in the future?

Duffus: I’ve gone back and forth between abstraction and realism. I will be making collages and abstract landscapes and then see something photorealistic and it will inspire me to see how far I can get with realism again. When I was making the paintings that were in “Fear of Drowning,” I started to make abstract paintings with my palette scrapings as a way to free myself from the image and recapture a sense of play. I know I’ll always work in both modes.

Kurt, 2018. 11" x 14" oil on panel. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery

Sand Castle, 2017. 24" x 24" oil on panel. © Justin Duffus. Courtesy of Justin Duffus and Linda Hodges Gallery