School portrait of McNair Evans

When asked about Begin Anywhere: Paths of Mentorship and Collaboration, a project realized as a book and an exhibition hosted by SF Camerawork, photographer McNair Evans described its origin as “a sense of overwhelming gratitude.”

Evans, Amanda Boe, and Kevin Kunishi experienced dynamic professional and personal growth through working with mentors during and after completing their graduate degrees in 2011. Through conversation, the three determined that a collaboration focused on the challenges and benefits of mentorship was a fitting way to thank those who had so profoundly influenced their respective practices.

In 2012, the primary artists contacted their mentors, and those who would become their mentors - Todd Hido, Alec Soth, Mark Mahaney, Mike Smith, and Jason Fulford - to ask about their interest in participating. Five years on, after multiple rounds of photographic exquisite corpse maintained via regular mail, word games, and the production of new work, the primary artists seek to answer the question posed by curator Monique Deschaines: “how do you show mentorship?”

Humble's Senior Editor Roula Seikaly interviewed Evans, Boe, and Kunishi about this unique project, and how being both mentee and mentor has impacted their work.

© Amanda Boe

School portrait of Amanda Boe

Roula Seikaly: How would you describe your relationships with your mentors before and after the project was completed?

Amanda Boe: Before I worked with Todd Hido and Jason Fulford, my work was all over the place and I needed some direction. I felt extremely lucky to have the opportunity to engage with them individually and learn from artists who inspired me. While mentoring with Todd, I ended up working as his assistant and studio manager for several years. Jason and I corresponded via email, since I was living in California at the time. I’m still in touch with both of them.

McNair Evans: That's a good question, and a lot of things come to mind immediately. In many ways, this project has caused a shift in the mentor/mentee relationship in that the mentees - myself, Kevin, and Amanda - were leading our mentors through these collaborative exercises. We were the ones with the bigger understanding of how all of this could come together, and they were trusting us to act not just with integrity, and to work with a certain level of professionalism and quality. That role of trust and responsibility switched, which has been fascinating. I've learned more about my mentor's work and their processes, how they produce their work, how they approach projects. The beehive of activity that has been necessary to bring people together for a book and a show has reemphasized my appreciation and respect for them as artists. Their response and thoroughness and creativity and intelligence for every aspect of this has been a treat. It's been a complete re-education. Working with their work has been a pleasure, and this show has created an entirely new framework in which I've become their student all over again.

One really fun and informative experience for me with this project has been bringing together what we've called "mentorship text." Each of the mentees contributed a text component about their path to mentorship. I recorded all of my conversations with my mentors throughout the project and had those transcribed afterwards in order to have a record of it.

© McNair Evans

Seikaly: In the book, that's the red and blue text?

Evans: Yup, red and blue.

Seikaly: I read that last night, first as a singular text and then broken down by color. That was fascinating. It can be understood from both the perspective of a linear conversation and then as the two blended. I wasn't expecting it to make as much sense from both perspectives. I also love how it looks on the page!

Evans: Thank you! It started out as 230 pages of transcribed text that had to be whittled down, but I think what emerges are the key points or exchanges with my mentors over the years and more immediately. It begins with photography, how to approach and edit a long term project, ideas about career, and even some self-reflective language from the mentors themselves. For me, it's parallels and conflict and then finding agreement, and that push and pull is really reflective of what it's like to be a student or an emerging artist.

© Amanda Boe

Seikaly: Short of a dedicated collaborative practice, art making is or can be a solitary endeavor. Could you describe shifting into the mentee role, and how your mentors influenced the work?

Amanda Boe: Todd and Jason provided different perspectives and challenges that informed my process of making photographs. Some of the most significant lessons I learned about photography came from observing Todd’s practice firsthand. Todd essentially taught me how to see by exposing me to his entire process, which helped shape my own way of working. Through his editing and sequencing process, I saw the potential of a suggestive narrative to influence the meaning of the work. He would often say things like, “It’s not my job to create meaning, but only to charge the air so that meaning can occur.”

Jason and I discussed visual association between images, and I began to see the world differently, noticing associations everywhere. Our conversations also focused on “collecting” as a method of photographing, looking at a subject in every possible way and literally collecting several different viewpoints and details. It made me go beyond the usual shortlist of ideas and be open to situations that came my way.

Seikaly: McNair -- In terms of your work, what's the takeaway from Begin Anywhere?

Evans: For me, it was a shift or reconfiguration or what I consider the outcome of my work to be. Prior to the outcome of Begin Anywhere, all of my work manifested as archival fine prints that would go in a frame or portfolio box. Then I took on Echoed - a collaborative project realized in my hometown of Laurinburg, North Carolina that involved digitizing the town’s newspaper archive, building an interactive website, and producing public murals. That was completely empowering and rejuvenating. With that came a change in audience, and that has been one of the most rewarding parts of these collaborative projects. The audience has fundamentally shifted from fine art connoisseurs to more of a general public. I think the audience for the SF Camerawork exhibition is as much aspiring photographers as it is enthusiasts and general audiences.

© McNair Evans

Seikaly: Amanda -- do you think of your practice in terms of popular phrases including "emerging" or 'mid-career?" Did this project affect how you think of your work on a professional temporal scale?

Boe: I don’t really think of my practice in those terms, but this project certainly made me reflect on how my work has evolved over past few years and how I was influenced.

Seikaly: There are photographs of correspondence between the group that were included in the accompanying book. What, if any, is the significance of work shared by post, as opposed to email attachments?

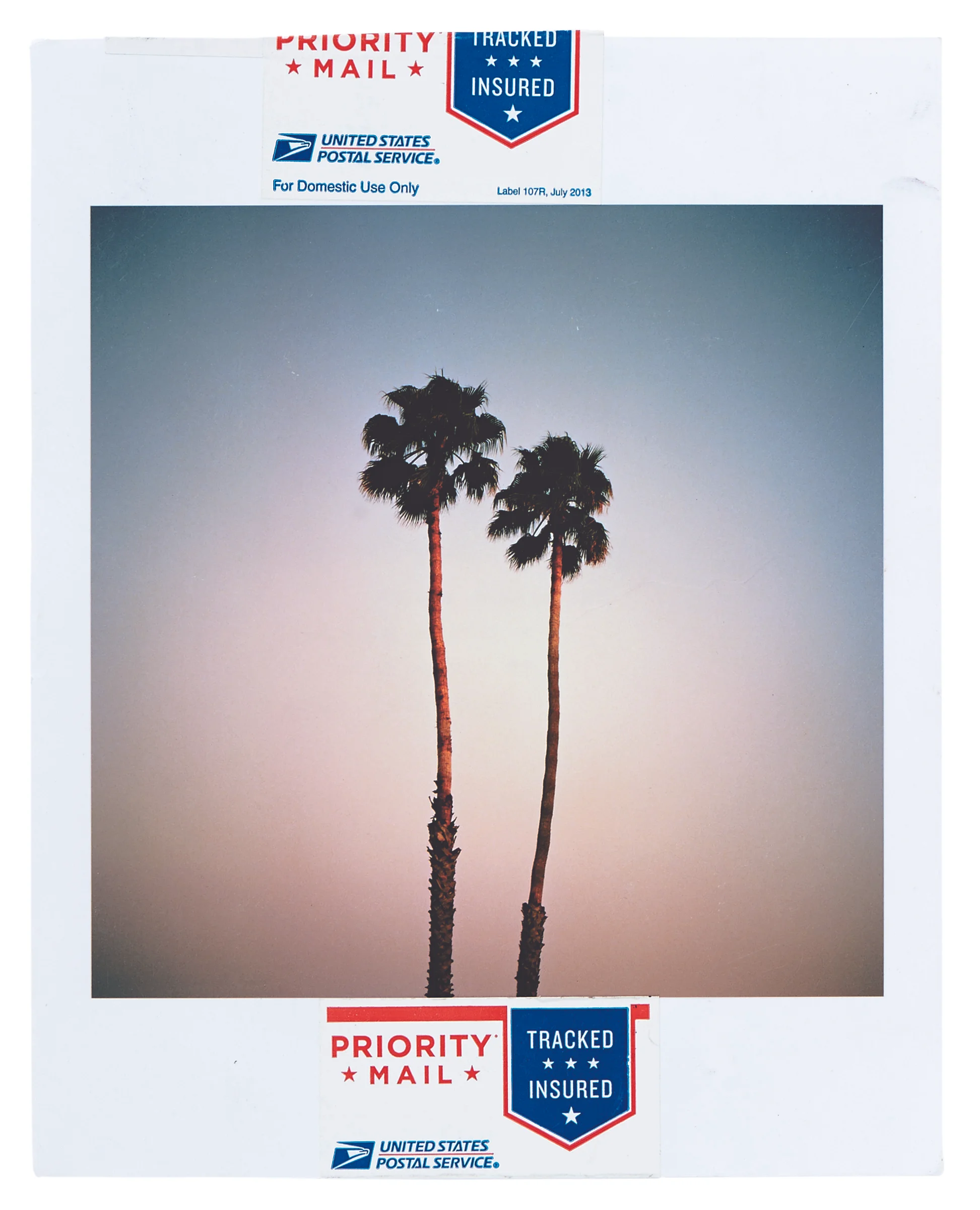

Boe: Exquisite Corpse was an engaging, tactile exchange that could not be replicated by email. It involved mailing prints without any packaging around the country and over to the Philippines for nearly 8 months. During the process, some of the prints got lost in the mail. When I was mailing one of my prints for the second time, a postal service employee asked me if we were testing the USPS. I told her we were putting our trust in the USPS.

Exquisite Corpse © Amanda Boe

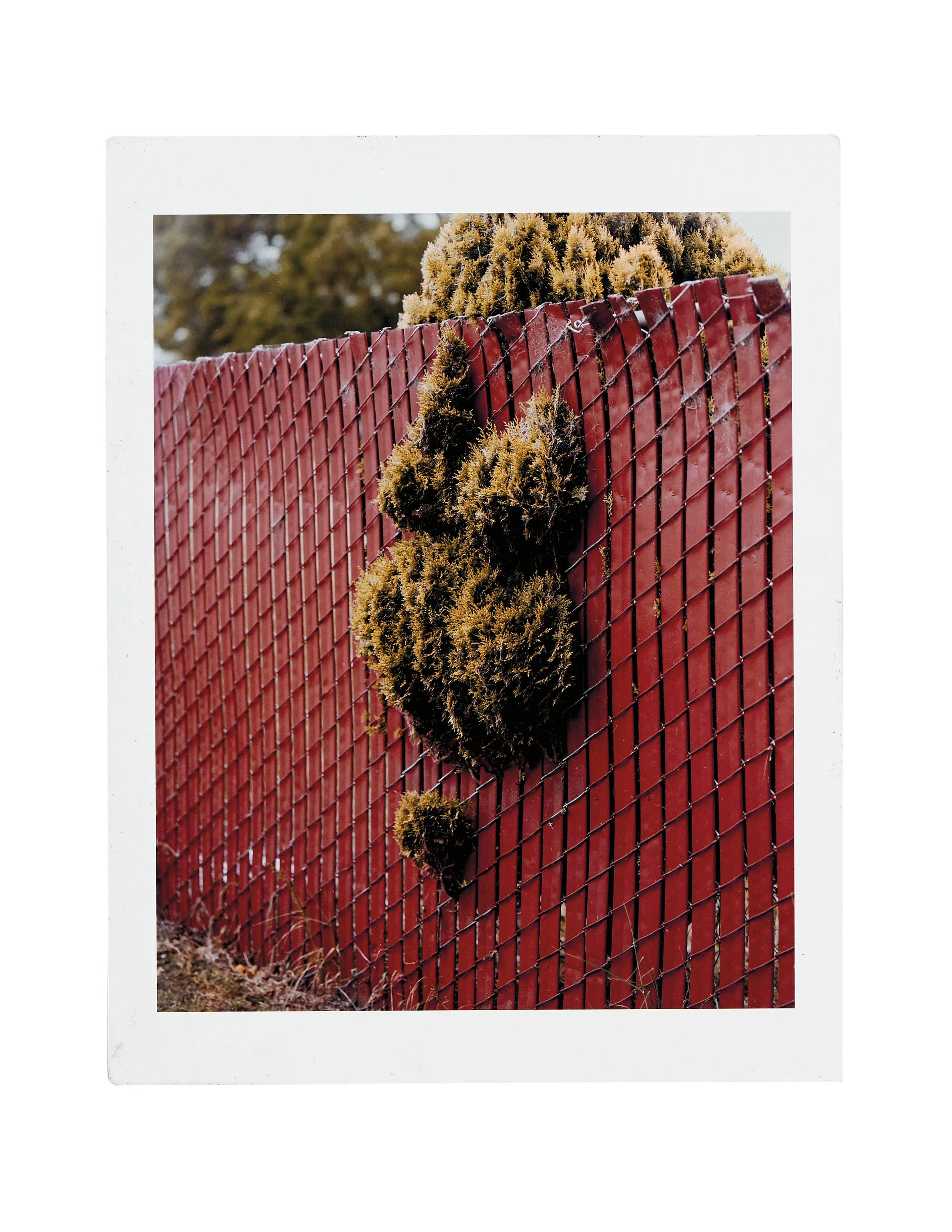

Exquisite Corpse © Mark Mahaney

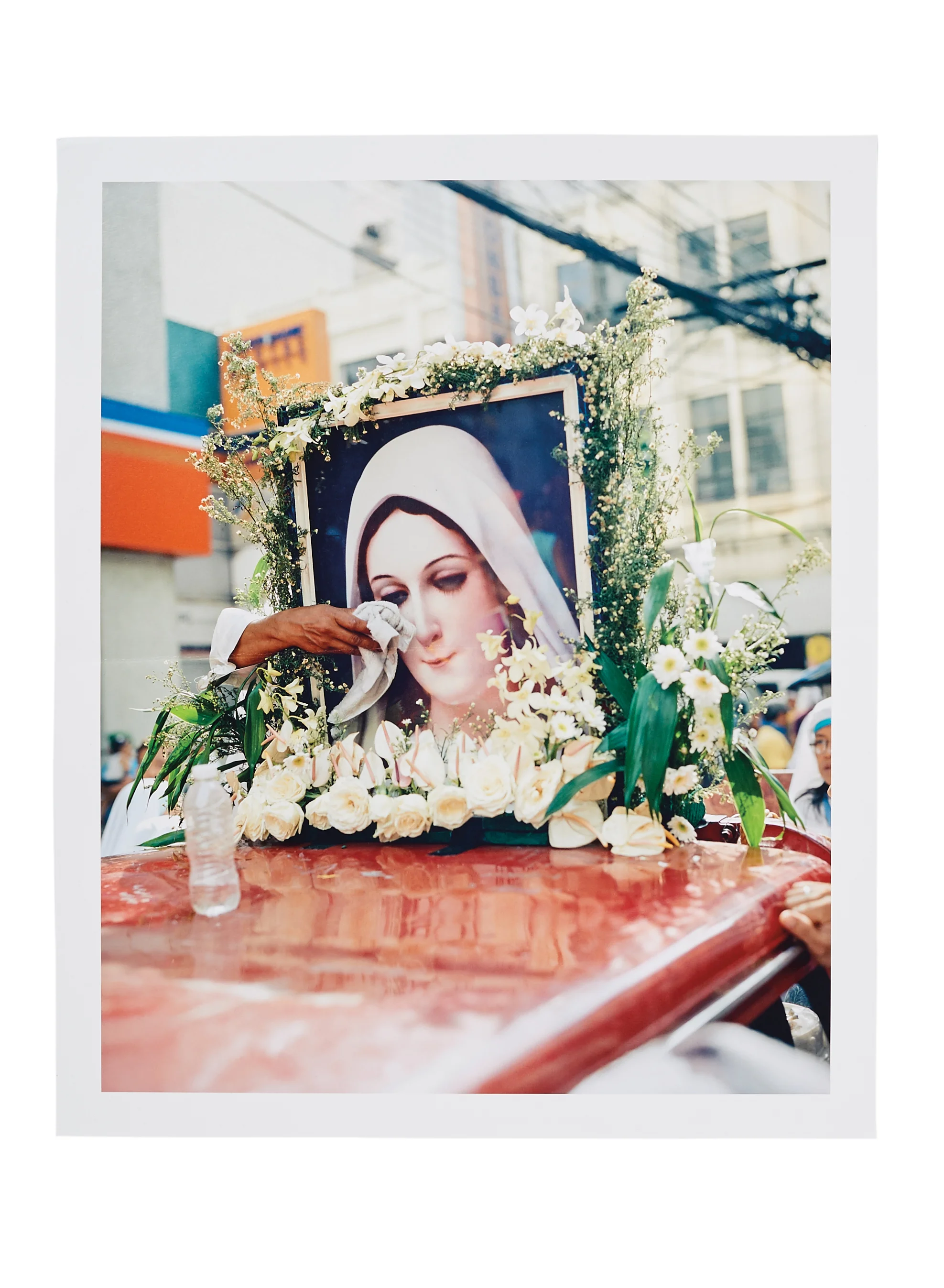

Exquisite Corpse © Kevin Kunishi

Seikaly: Kevin writes about Jason Fulford and Mark Mahaney encouraging him to get closer to the Nicaraguan subjects he photographed, and how that insight was both useful and humbling. I'm wondering if you experienced similar critiques, and how that was received?

Boe: When I first received feedback from Jason, he challenged me to think about the content in my work. At the time, I was photographing a couple projects that were both personal in nature and perhaps a bit too ambient. He asked me “what story do you want to tell, and how does it transcend your personal exploration to engage an outside viewer?” That made me step back and reconsider my approach. I still think about that question a lot when I’m making work.

Seikaly: McNair, what kind of critique did you receive from your mentors, and how did you take it? Your comment about happily being a perennial student suggests you might have taken whatever they suggested was welcomed. How did that feel for you?

Evans: Two weekends ago, Alec (Soth) was in town and we went for breakfast. He was reading the text from our exchanges and noted how hard he was on me. I think he pushed me to understand the particular emotional and intellectual space from which my work comes. I want to understand the space where that lives, and how my work relates to it. Often times, he would point out the aesthetic accomplishment of an image, but would follow up by saying that it wasn't relevant to what we were doing for the project. It helped me to think about those narrow parameters and to stay focused.

© Mark Mahaney

Seikaly: Are you working either formally or informally with students? Has being a mentee changed how you work with artists who ask you to be their teacher or mentor?

Evans: To be honest, I'm afraid of the bureaucracy and administrative paperwork involved in teaching. I'm on faculty at SFAI, but never taught a class.

Seikaly: Does that mean that if a student is interested in talking to you, do they refer them?

Evans: Sort of. I run a fairly steady six-month internship program, and that's usually two interns at a time working on separate days of the week for a minimum of six months. Our arrangement is that every day the interns come, they work six hours, we eat lunch, and then we spend an hour and a half on their work. We're thinking about editing and process, generally for long-term projects. I love it. It's my favorite part of the day.

Seikaly: Within that context then, with interns, has Begin Anywhere impacted how you work with interns?

Evans: One intern I'm working with now is working on a long-term project and we're focusing on editing, which is new. We're defining that process for him, looking this week at issues of scale and size whereas the week before we were working just on the image edit. I found myself returning to lessons from my mentors to better help and instruct this person, to ask better questions. I'm really happy about that.

Seikaly: It sounds like it's been such a positive experience for you all around, including the interns you work with now and in the future, not to mention your photographic practice.

Evans: It has been. I couldn't be more pleased with it all.

© Kevin Kunishi

School portrait of Kevin Kunishi

Roula: Kevin, had you worked with a mentor prior to working on Begin Anywhere?

Kevin Kunishi: I lived in Nicaragua for about two years. I was doing a project on the US-backed Contra War in the 1980s and 90s. I was living near the Honduran border, in fairly remote villages, and that's when I started working with Jason and Mark. Every Saturday I would take a 3.5 hour bus ride to the city of Jinotega, the only place that had electricity, and then we would have dialogue by Yahoo IM. Jason and Mark have very different styles. Jason planted little seeds regarding literature, and he would push me in different directions and give me things to consider. Mark encouraged me to get closer, and asked about my intentions in terms of engaging with the people I photographed.

Seikaly: That whole exchange between you and your mentors took place before Begin Anywhere?

Kunishi: Yes, well before. That was around 2010.

Seikaly: At the time, before Begin Anywhere, what did you take away from that mentorship experience? Did those exchanges influence your learning process, or how you approached that project?

Kunishi: Of course. It has to be a struggle. There's a push and pull. It's part of the process. I think it's about challenging yourself, challenging ideas, and that's what they posed to me at the time. Both Jason and Mark are so good at what they do, and I really appreciated interacting with them in that context.

© Kevin Kunishi

© Kevin Kunishi

Seikaly: Do you work with students, either undergraduate or graduate? Now that you've been a mentee, has your teaching style or how you approach working with students changed?

Kunishi: Definitely. I've taught at Sacramento State and a few other local universities, and I understand much more that it has to be treated as a commitment. If you're going to do it, do it. Another thing is that I better understand how to communicate with different students. It's about finding the right language that works with each student as an individual. Once I find that hook, and I start to see them producing work, it's very satisfying. Encouraging students to challenge themselves, to strive for honesty and transparency, as I experienced the same push from my mentors Jason and Mark was a very important lesson.

Seikaly: In terms of future projects, do you have a sense of how mentorship has impacted your practice?

Kunishi: It's hard to say right now. I'm hyper critical of myself and what I'm doing. Overall, I'm certain that participating in Begin Anywhere and working with Jason and Mark has made me a better photographer. I'm much better, and much more comfortable, in challenging my preconceptions and assumptions and asking much more difficult questions particularly in terms of the subject matter I pursue.