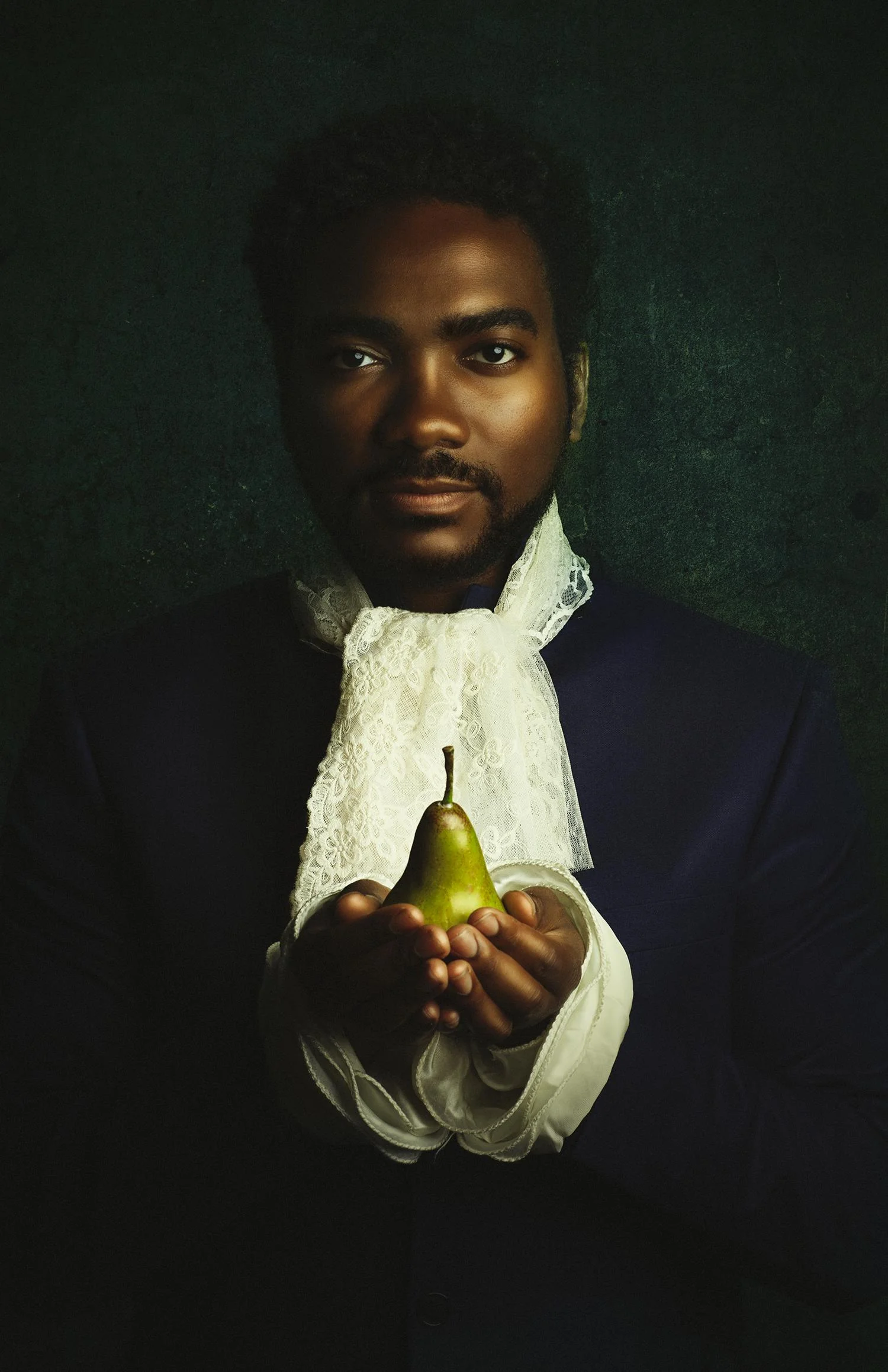

Queen Mary, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

San Diego-based photographer Alanna Airitam describes her urge to produce The Golden Age, a series of monumental photographic portraits that celebrate African American and African Diasporan identity and counters their omission from visual narratives in much of western art history, as unrelenting. Friends and acquaintances agreed to sit for Airitam, who situates her subjects in lush sartorial and environmental settings that recall the personal and material abundance portrayed in Dutch Renaissance portraits. Working photographically, rather than with oil paint, the artist creates a forum in which we’re invited to consider matters including identity, consumption, and who is celebrated.

Humble Arts Foundation senior editor Roula Seikaly spoke with Airitam about the project’s origin, relatable vulnerability between photographer and sitter, and challenging both stereotypes and the impermanence of popular culture through familiar media forms such as portraiture.

Interview by Roula Seikaly

Saint Abyssinian, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Roula Seikaly Thanks for agreeing to speak with me. We are really excited to share your work with our readers.

Alanna Airitam: Thank you for this opportunity!

Seikaly: I understand that you're a self-taught photographer. Why did portraiture became the central focus of your practice?

Airitam: It's kind of funny, actually. My dad was an artist who painted and drew. As a kid, I watched him, and I think that's where I got my "training" from. I would try to do what I saw him doing, but I couldn't draw anything other than people. I got really good at drawing people's faces and their facial expressions. I liked focusing on that. At some point in time, the body fell away as I knew I would never been good at drawing hands or other body parts. I can go back through old notebooks and see find all these floating heads. It's frustrating, too, for someone who wanted to be good at art that I could never really get past that phase.

When I decided to make photography my focus after years of going in and out of different art practices and being a full-time graphic designer, I decided to dedicate my time and focus to understanding light and shadow. It always came back to people. The strange thing for me, though, is that portraiture is scary. A photographer has to be really open with the people they work with, which encourages them to be open and produces a good shot. I have a hard time with that openness or vulnerability. Portraiture is a way for me to work through my own stuff. I think that the more I work in this, and it's a slow process, the better my photographs are.

Dapper Dan, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Seikaly: You mention vulnerability. Would you say that is a relatable point for your sitters as well?

Airitam: Possibly. It's definitely not a conscious thing. The people who I work with are people I know, some I don't know but are connected to me through friends. I try to find a base relational level where we can start and then go from there. I've learned to not my hide my weirdness, and that's liberating. What helps me is going into the shoot with an idea or character in mind. If I can stay focused on that, it's easier for me to give them direction, which in turn eases their nervousness.

Seikaly: You said that people you photograph are friends, or friends of friends. How would you describe the interactions that lead to and continue through the portrait session? Do your sitters see examples of your work before they are photographed? Does that give them an idea of what they can expect from the experience?

Airitam: I usually put together a mood board before they come in. We'll email a bit before we meet, and I'll share examples of past work and try to give them an idea of what I want to create. The mood board images are ideas that I want them to keep in mind in terms of pose, mood, or feel. That gives them something to go on. Once they come in, we'll talk about the project and its origin. I try to find a balance between my vision, and what the sitters bring to it. So, the project has its collaborative elements for sure. I'm always pleased with what they bring to the experience.

Saint Sugar Hill, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Seikaly: As I was preparing for this interview, I brushed up on art historical readings and contemporary exhibitions that highlight how Africans were seen or portrayed by European painters during the Dutch Renaissance. I came across the 2012 exhibition Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. One of the curatorial notes says that though there are many extant portraits, there aren't many names attributed to the sitters. I notice that you don't list the names of your sitters either, instead titling the pieces after streets in New York's Harlem neighborhood. Could you talk about that?

Airitam: I title the pieces after landmarks and street names, yes. There's one that I titled "Dapper Dan," and that's the most contemporary of all of them. He's an iconic Harlem figure. When I saw the finished image, I thought that was the only suitable title for that piece. He's very debonaire and fashionable.

Seikaly: In not using the names of your sitters, are you concerned about an ongoing erasure of Africans or African Americans from an overall visual narrative in western art?

Airitam: That's a really good point. It wasn't part of my thinking, although it may be moving forward. I understand that when enslaved Africans were brought to the United States, their prior identities were erased. Referencing that wasn't my intention. I was and am thinking about pay homage to the Harlem Renaissance and call attention to the streets and landmarks that are quickly being eaten up as Harlem is gentrified. Too many of the historic buildings in the neighborhood weren't designated as landmarks. In the 1980s, they were crack dens, and now they are Marc Jacobs stores. We're losing a crucial part of our history, and that's devastating.

Saint Apollo, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Seikaly: I think it's a beautiful note that you make to Harlem as a neighborhood and the struggles it and the residents have faced over time. There doesn't seem to be anything that can stop the momentum of gentrification other than those who work doggedly at the neighborhood, city, and state level to make sure that history isn't forgotten. I'm curious about the Renaissance portraitists or other painters and images that influenced this project?

Airitam: Definitely. Where influence is concerned, I try to find a balance between research and imitation in this work. I don't want to mimic what I see in these classical scenes. What I try to tap into is what I was drawn to in art as a child. I love still life paintings. I love the aesthetics and drama of Baroque compositions. To not see people who look like me represented in that way left me with the feeling that I would never belong in a museum, or that I could be an artist.

I thought about all of that, and imagined what it would be like to create images that could exist side by side with the paintings I love. I'm moved by Frans Hals portraits and Rembrandt's lighting. I was also curious about what portraits of Africans in pre-modern European art, and came across pieces by Gericault and Gerome that stuck with me.

Saint Lenox, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Seikaly: When did you start this project?

Airitam: I started in May 2017, so not long ago. The idea for the project, and the image “Queen Mary,” in mind for about a year. I didn't know what it meant, or what I was supposed to do with it. I couldn't escape the image of the key in her palm and the flowers. So, I started shooting. The more I shot, the more the project came into focus for me. I've never worked this way before. Every day, it felt like something new was revealed to me. It's such a gift, and such a surprise. I shot really fast, often several days a week, but the direction was very clear. When I stepped back from it and let the emotion set in, it was a profound experience.

Seikaly: I would not have guessed that you started this project less than five months ago. It's so complete in terms of the subject matter, the overall aesthetic, and your description of it.

Airitam: It really is. It's one of those moments where if I can get out of my own way creatively and psychologically, whatever is meant to come out will come out.

Saint Nicholas, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Seikaly: What more would you like to see come of this project?

Airitam: I took a break for a while and have been working on the Gratitude series, which was a way for me to release extra energy and ground myself. It was also a way for me to get back into commercial work before starting the next series. It's accompanies The Golden Age, but isn't necessarily part of that series. I'm working through ideas of inclusivity and identity in Black culture. What will be carried over will be the floral elements, which I really love. I'm working on three portraits that address Black female stereotypes, and in order to really concentrate on that, I need to get The Golden Age out of my head. It's an unfolding story.

Seikaly: How large are these pieces when they are printed, and how do you frame them?

Airitam: I've printed the pieces, but have not framed them. The gilded frames that would round out the overall opulence of the pieces are, as you would imagine, very expensive. I'll print them to life size, and I want to hang them at eye level. I'm working through framing strategies that call up that opulence, but that won't break my bank.

Saint Madison, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Seikaly: What about the cultural moment that was the Harlem Renaissance most inspires you?

Airitam: What comes to mind for me is so much color and joy. It was a celebration. It makes me so happy to think about Black Americans capitalizing on a moment when they could be themselves. It was remarkable. It was a remedy to the all the chaos that preceded it. Even more than the photographers of the time, the people who influence me were Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, and the jazz artists. They captured who we are as a people. I wish that we could recreate that explosive creativity.

Seikaly: That tags into a question about competing media narratives and how African Americans are portrayed. One one hand, it's celebrities like Beyonce and Kanye West. On the other, it's the brutality of the police state bearing down on African American men, women, and children. From your perspective as an artist and African American woman who lives amidst these narratives, do you see your work fitting into or deviating from that context?

Airitam: That's a tough question. I appreciate pop culture, but it doesn't leave a lasting impression. Selfishly, I like to think my work has more meaning for people. I don't want my work to be consumed as quickly as what's seen on Instagram. Africans Americans have been taught that we're not suitable for society. We're scary. We're angry. The Golden Age offers another perspective; we're not one dimensional. I think The Golden Age portrays dimensionality in African Americans and the lives we lead. The series asks viewers to see something other than the stereotypes that too often describe people of color. That's my great hope for this series.

RS: Thanks again for reaching out to Humble Arts Foundation!

AA: Thank you for interviewing me!

Saint Minton 2, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Saint Strivers, 2017 © Alanna Airitam

Bio: Alanna Airitam is a New York born, Dallas raised, San Diego rooted portrait photographer. A former cubical occupant with a background in design and brand strategy, she now supports her fine art through commercial photography. A lifetime studier of people, Alanna has always been fascinated with storytelling through portraiture. Currently, her work focuses on searching for hope in how we understand identity, representation and belonging through our warped social lenses.