The Brocade Walls, 2003, © Tina Barney. Courtesy of Tina Barney and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

The question How To Live Together, the title of an exhibition at Kunsthalle Wien running until October 15, is answered within five minutes of entering the first of two massive gallery spaces dedicated to the show: not easily, cacophonously.

Its mixed-media nature means that the myriad installations, videos, sculptures, photographs, and even an animatronic talking sculpture of a life-sized man combine to immediately overwhelm the viewer. How do we live together right now? Like this—with endless voices talking over one another ad nauseam, with countless noises thrown into the fray, with no one able to focus or listen in the face of so much distracting stimulation. The next question with which the exhibition grapples, then, becomes how can we live together—and how can we do better than what we’re doing right now?

Exhibition review by Deborah Krieger

Installation photo © Stephan Wyckoff

How To Live Together appears to have been a staggering curatorial undertaking. The simple issue of deciding which artists get to have their audio components broadcast into the gallery space and which have to incorporate headphones into their works probably took hours of negotiation. At over thirty artists, it would be nearly impossible to review each artist’s contribution separately, so instead this review will consider several pieces that seem thematically central to the mission of the show. How to Live Together is hardly an abstract thought experiment; it has an overall message and mission to spread about coexistence—not only among humans, or among nations, but between humans and the earth itself.

The Antlers © Tina Barney. Courtesy of Tina Barney and Paul Kasmin Gallery

A selection of Tina Barney’s 2000s large-scale photograph series Europeans is a sly, affecting centerpiece of How To Live Together. The subtext of the photographs chosen from Europeans is like a wallop in the face once you understand what she’s done. How To Live Together displays ten or so of her photographs, each of which, at first glance, appears to depict a sort of essentialized European-ness. Here you have three young girls in dirndls, there you have a family portrait with all the grandeur of aristocracy adorning the walls—the standard idea, perhaps, of how many see the idea of Europe—elegant, probably blonde, with a certain je ne sais quoi that makes them particularly exciting to American sensibilities.

The Antique Shop © Tina Barney. Courtesy of Tina Barney and Paul Kasmin Gallery

Yet one key work turns the entire premise of an essential “European-ness” on its head: The Antique Shop, a photograph from 2002. A well-to-do white European family examines the goods in an antique shop—the father lifts his young son up into the hair so that the boy can fiddle with an ornate hanging chandelier, while the mother looks on nonchalantly. But in the background, just off-center, the other side of this blithe European-ness emerges—the simply-dressed owner of the shop, a woman of Asian descent half-hidden behind a doorway, who is clearly swallowing her anger at this family who is letting a small child potentially damage valuables without so much as a warning—without thinking of the potentially disastrous results of their actions. She even seems to be making a fist behind her back as she must accommodate these thoughtless customers, because who takes a toddler to an antiques shop except for people to whom consequences don’t apply?

The Bust #2. © Tina Barney. Courtesy of Tina Barney and Paul Kasmin Gallery

Other than this figure, everyone else in Europeans series as displayed in How To Live Together is clearly white, and having this clear divide creates a purposefully uncomfortable gap between the “Europeans” as stereotypically conceived and those who will never be considered as “real” Europeans by virtue of their racial or ethnic background. Taken together, Europeans can be read as a condemnation of this essentialist model of what it means to be European, and of the unchallenged sense of belonging and unquestioned European-ness that separates some from others.

Carrerouge © Mohamed Bourouissa

Photo Credit: Jorit Aust:

In what has to be a purposeful curatorial choice in the aforementioned vein, Mohamed Bourouissa’s photographic series Periphérique offers a rejoinder to the cracked façade of Barney’s aristocratic Europeans. Produced in 2006-2008, Bourouissa, a French artist originally from Algeria, tells a story of another “other” kind of European—in this case, the marginalized, lower-income youths from immigrant backgrounds who weren’t born with the innate surety of their own belonging in Europe. The subjects of Bourouissa’s photographs do not pose with their fine family heirlooms and silk-draped walls—they linger in dingy hallways, in the banlieues of Paris, in alley and highway underpasses. So to bring these two artists’ contributions back to the original question of the show: how do we live together? Answer: right now, we don’t, not while some people living in Europe are made to feel othered and invisible. How can we live together? By understanding, in this case, that European identity isn’t some immutable thing handed down from generations of kings, but is a constantly fluid notion that needs to include the people who don’t fit the stereotypical “European” mold.

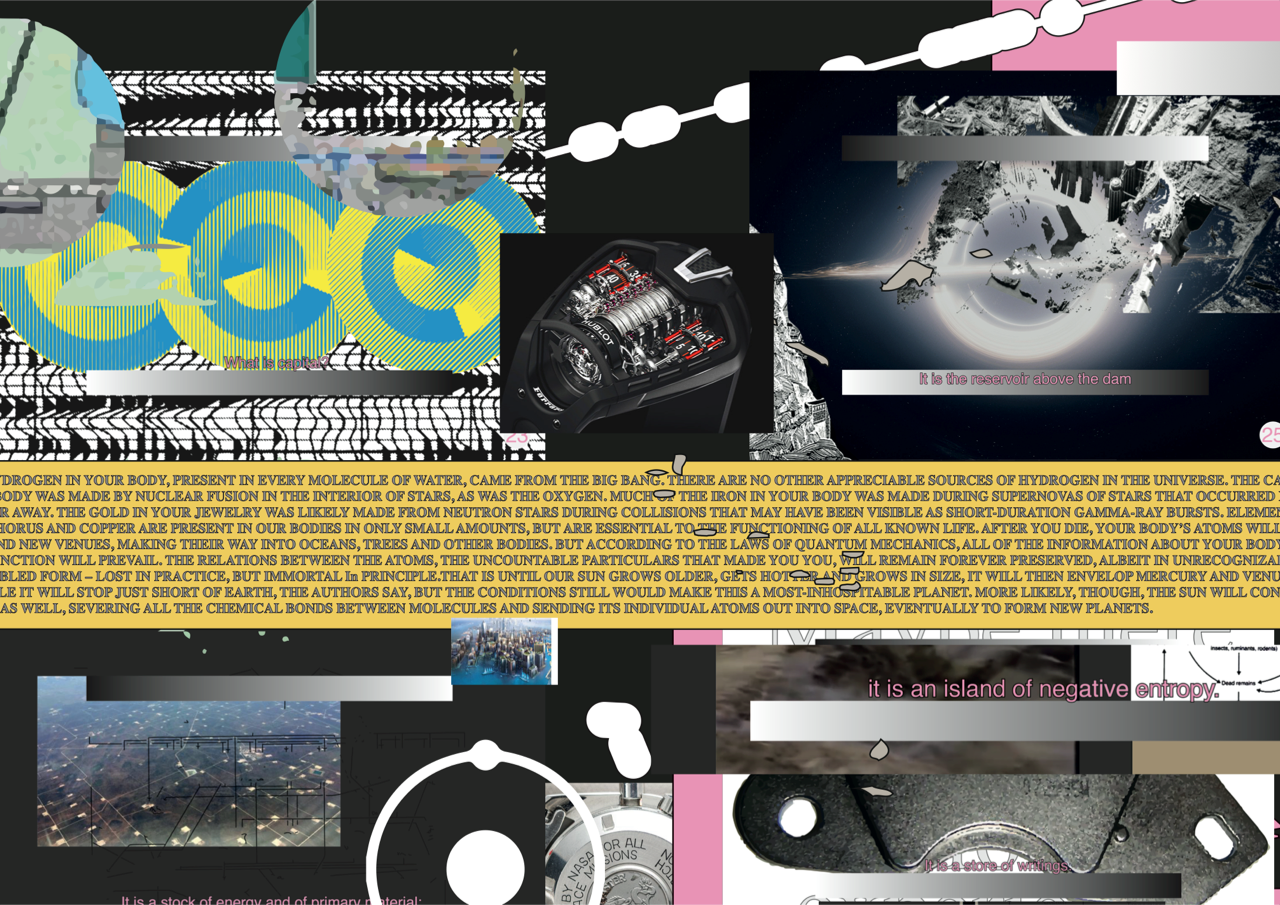

Physical Factors of the Historical Process—The Problem of Cosmic Calculation © Pedro Moraes

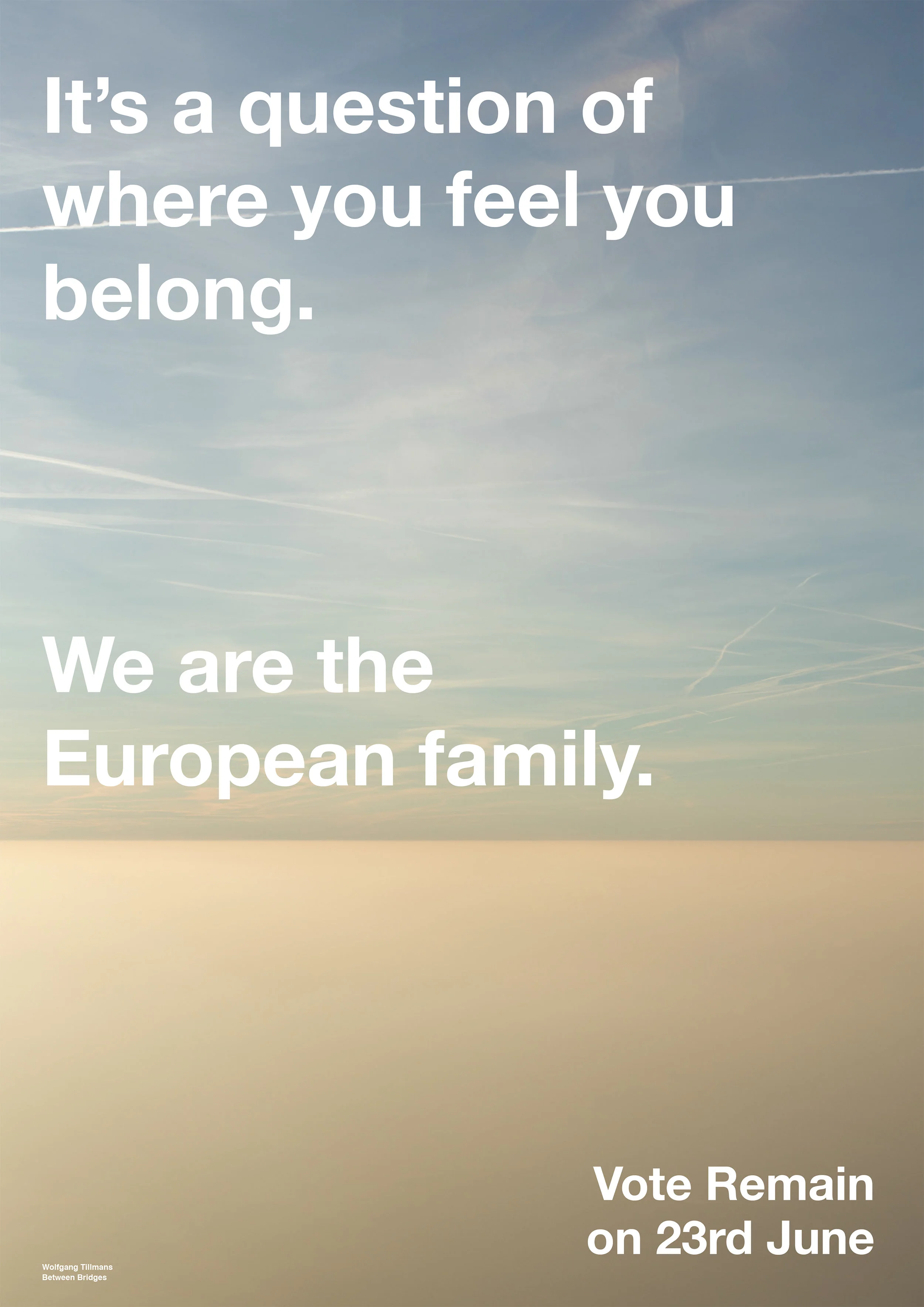

Wolfgang Tillmans, Anti-Brexit Campaign, 2016, Courtesy the artist and Between Bridges, Berlin. Photo Credit: Jorit Aust

The works in How To Live Together answer the central questions in different ways—including the aforementioned more cosmic level. Pedro Moraes’ Physical Factors of the Historical Process—The Problem of Cosmic Calculation comprises two large-scale double-sided posters depicting a range of scientific schematic diagrams, lines of text, drawings, and other collage-esque inclusions. He asks: ‘how do we live together?’ Not with one another as people, necessarily, but together with the world and with its resources? Again, not well, in Moraes’ view: humanity has harnessed too much technological power in its quest for energy without thinking of the repercussions and physical consequences to the planet. How can we live together? By accounting for these negative effects, and by recognizing how these negative effects on the environment circle back to affect humanity.

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Refugees- Italy Catania-Messina © Herlinde Koelbl

Towards the end of the overall exhibition experience, How To Live Together makes its political bend and bias absolutely clear, and boldly purports its overarching curatorial statement about changing the world. Wolfgang Tillmans’ Anti-Brexit Campaign and Herlinde Koelbl’s photographs of refugee camps, located near the end of the exhibition, ask the viewer, how do we live together? How can we live together? and answer, simply, with together, with solidarity and unity and compassion. The show’s title is then turned on its head: not so much How To Live Together, with a vague togetherness as the goal, but instead: How To Live? Together, with togetherness as the process and answer of living itself.