Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Robert E. Jackson has been collecting twentieth century American snapshots for decades, amassing more than 12,000 pictures. From unintentional visual decapitations to outer-space themed Christmas cards, Jackson's collection highlights the unique anonymity, and often unintentional artistry of his subjects. For years, Jackson was interested in only snapshots from the late 19th century to the middle of the 1970’s, but recently he has begun to collect 4 x 6 borderless snapshots. This format was popular from the late 1980’s to around 2007 and signaled the last generation of analog vernacular photography.

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

While bigger prints could be made, the 4 x 6 borderless drugstore photo represented the largest print size that was mass-produced and offered for family snapshots. It remained popular into the first decade of the 21st century even with the rise of digital photography. When the iPhone launched in 2007 (along with the Smartphone’s introduction in 2002), there occurred a drastic reduction and near demise of the physicality of the family photo album; and with that a corresponding slowdown in the popularity of 4 x 6 prints. Although it's still possible to get these made from digital files at Walgreens and other drugstores today, the cultural shift in how photos are shared - now predominantly via Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram - has dramatically reduced their production volume and use as a shared physical object.

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

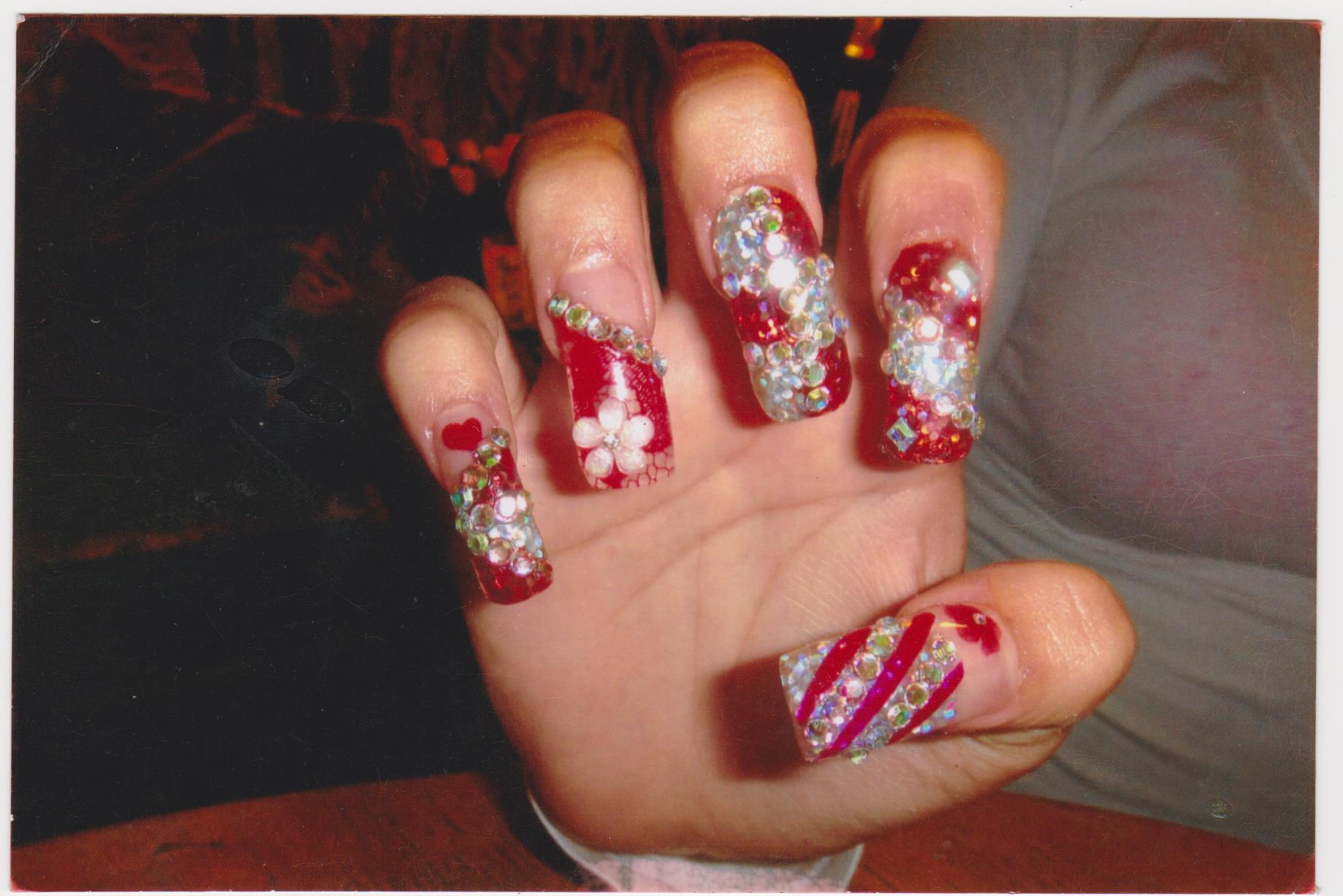

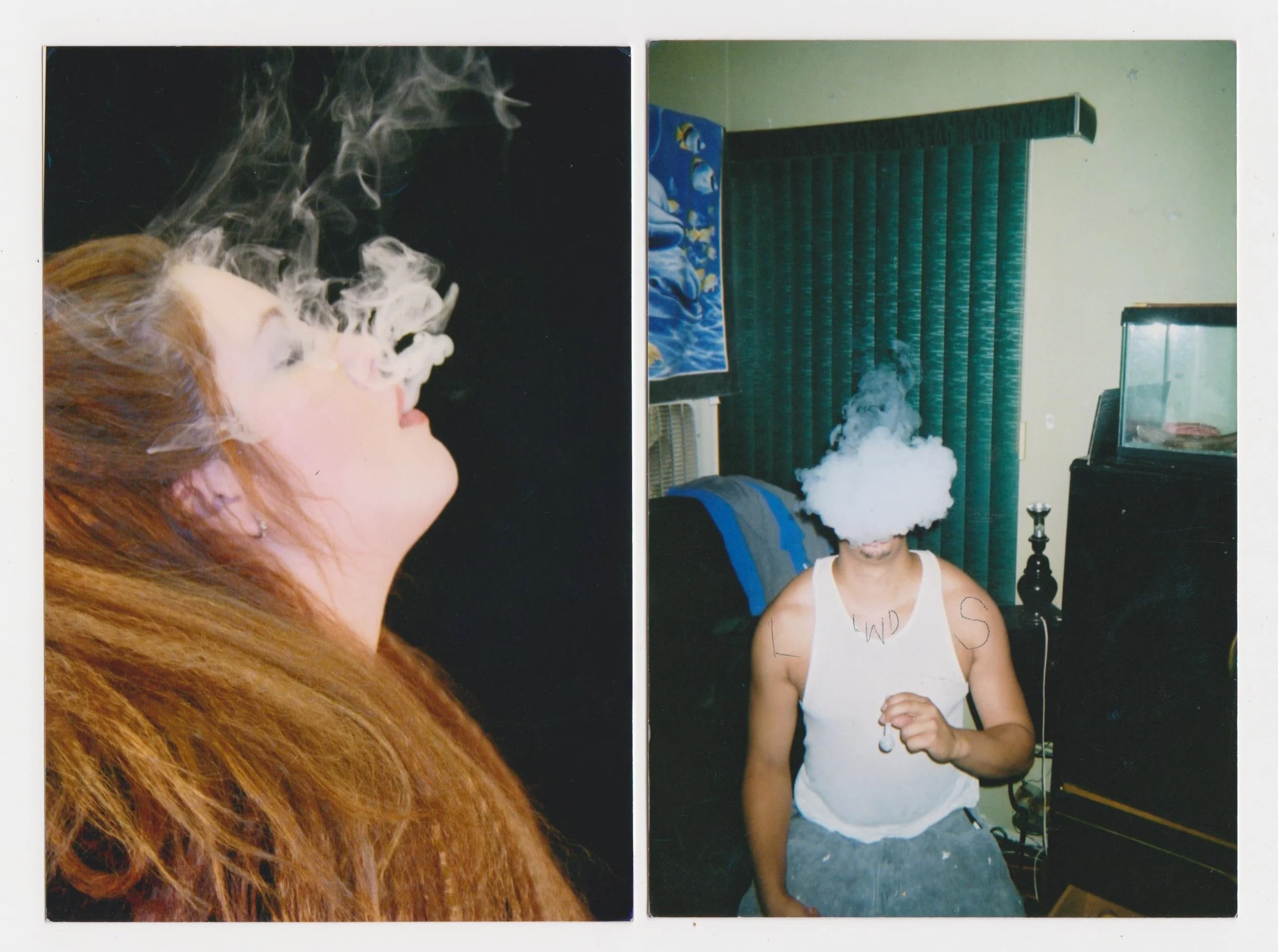

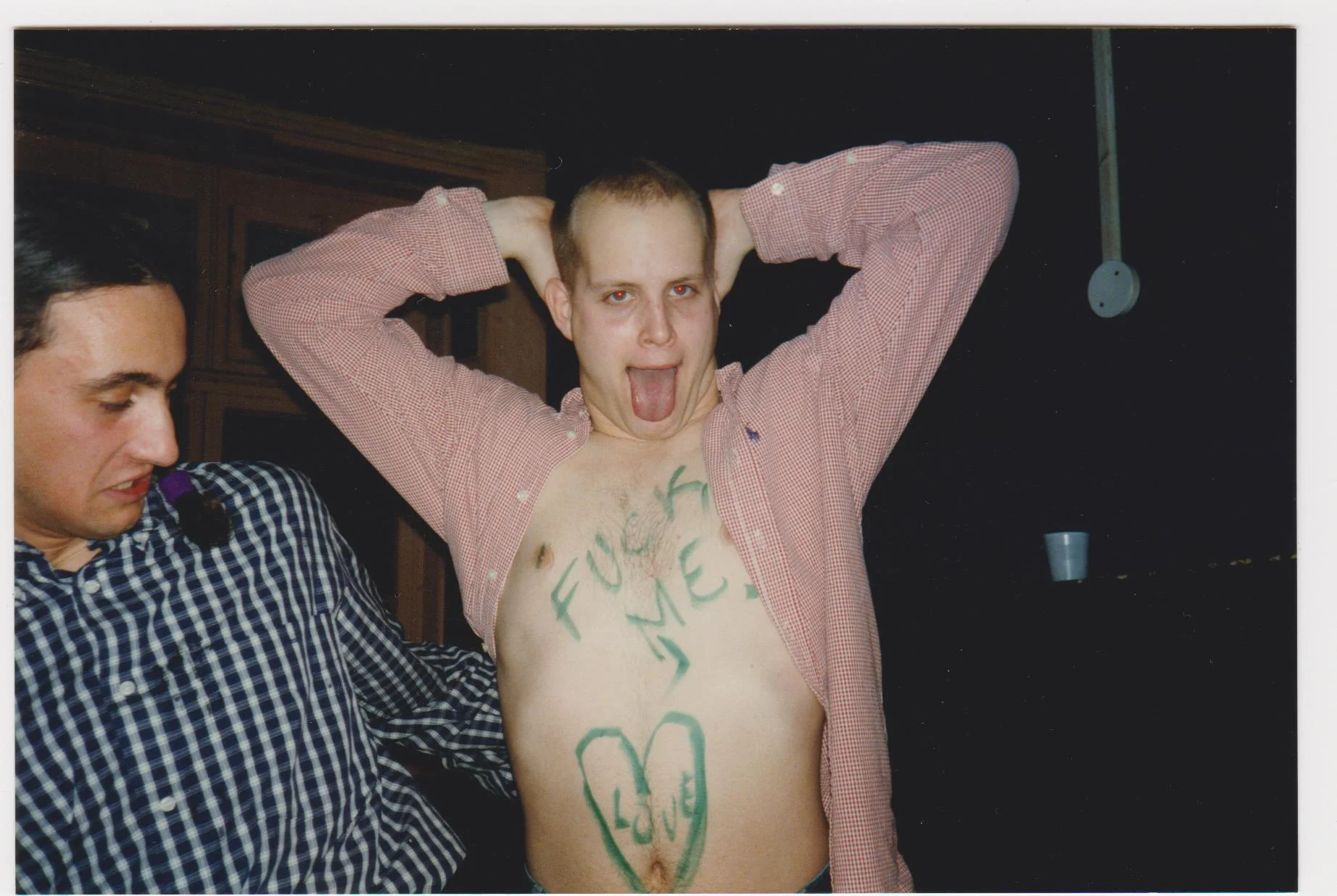

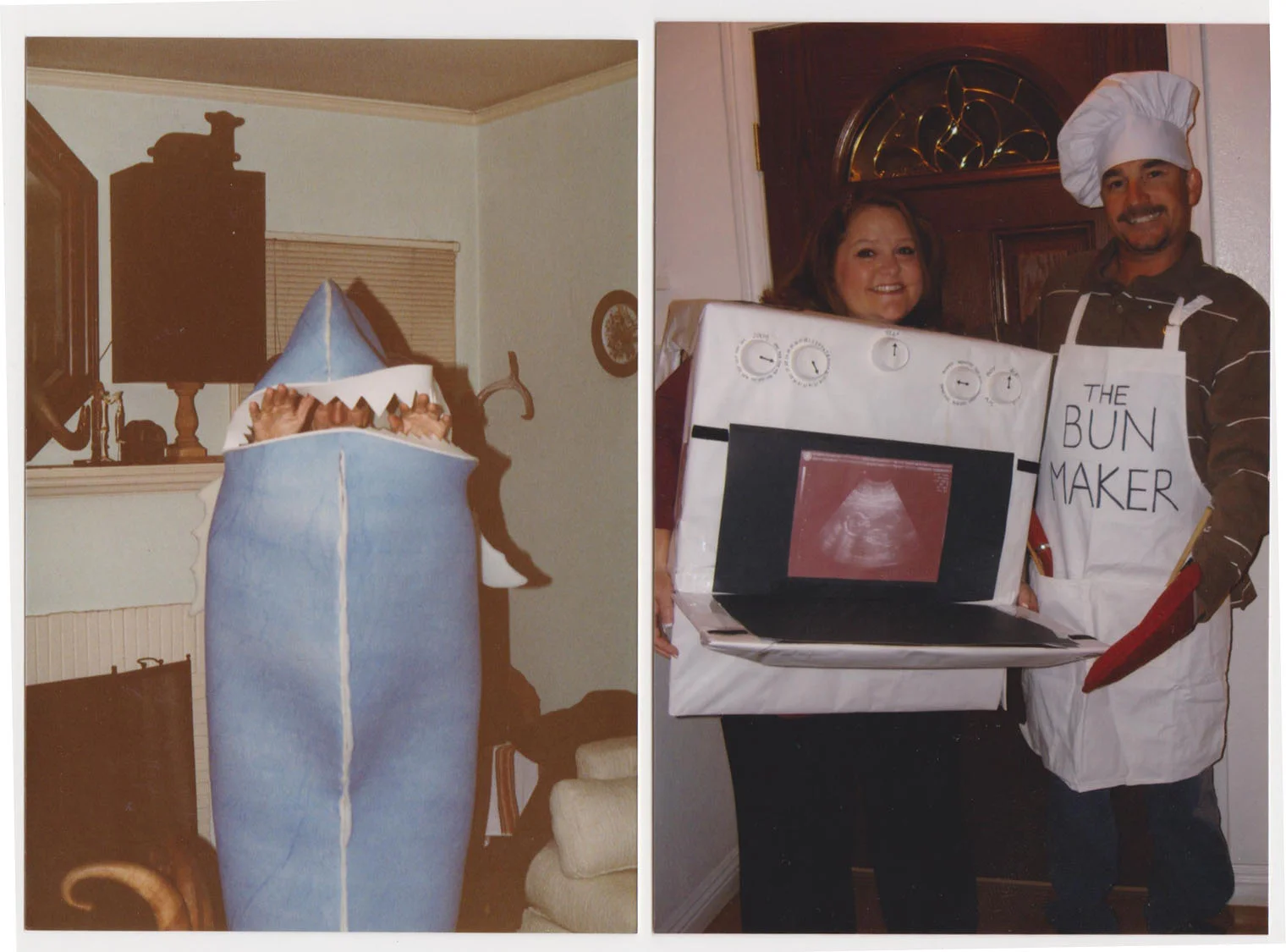

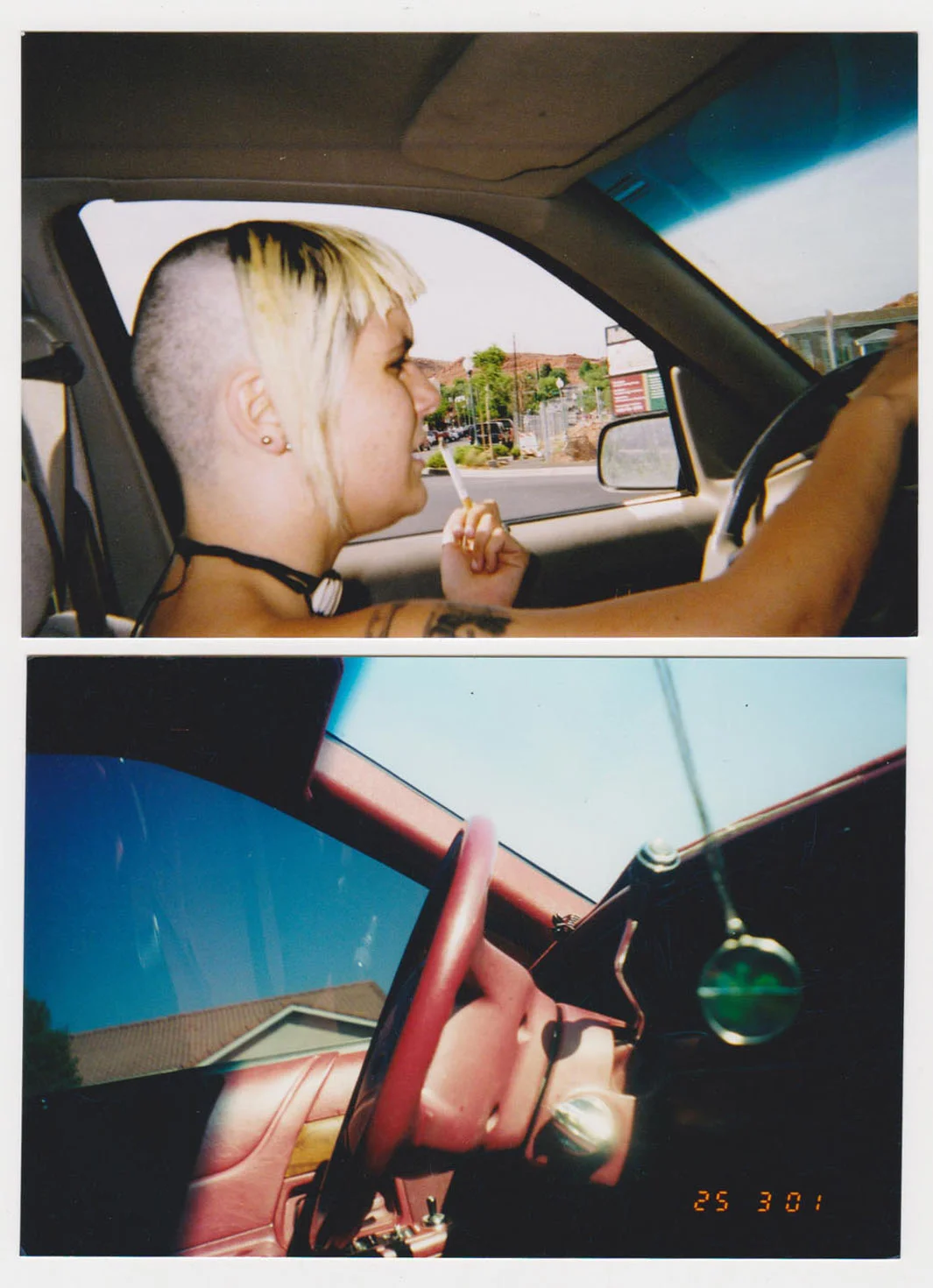

For Jackson, the popularity of the 4 x 6 borderless snapshots marked a change not only in physical format, but also suggested a significant cultural shift in how people photographed themselves for their families and friends. Most notably, the subjects displayed new modes of performing for the camera versus what had been the norm in past eras. "Photos from this era seem to be more raw and unrefined in terms of subject matter than earlier snapshots," says Jackson. He notes the increase of images of tattoos, piercings, and generally uninhibited presentations of the self at parties and in daily life.

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

In one photograph taken at close range, for example, a woman holds her lips open to show her new grills. Her face is blurry, the camera’s lens likely auto-focused to a Ford Focus car in the background. In another photograph, a man in his early twenties stretches his arms behind his head, tongue sticking out, his unbuttoned shirt revealing the words ‘fuck me’ on his chest in green magic marker above a similarly scribbled heart. Maybe he's at a bachelor or a fraternity party. More likely than not, he's wasted, and enjoying it. Another photo is shot in first-person as a woman slides down a waterslide. Her leg juts into the foreground, toes painted, a couple bandages cover some blisters on her feet. The rest of the frame is filled with grainy turquoise and other fellow watersliders in the background. Another image, taken from just below the water's surface, shows a man's body, neck-down, fully unclothed save for some flippers on his feet. In Jackson's mind, these images and others suggest an evolved kind of freedom and casual relationship to the camera and its use to document everyday joys.

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

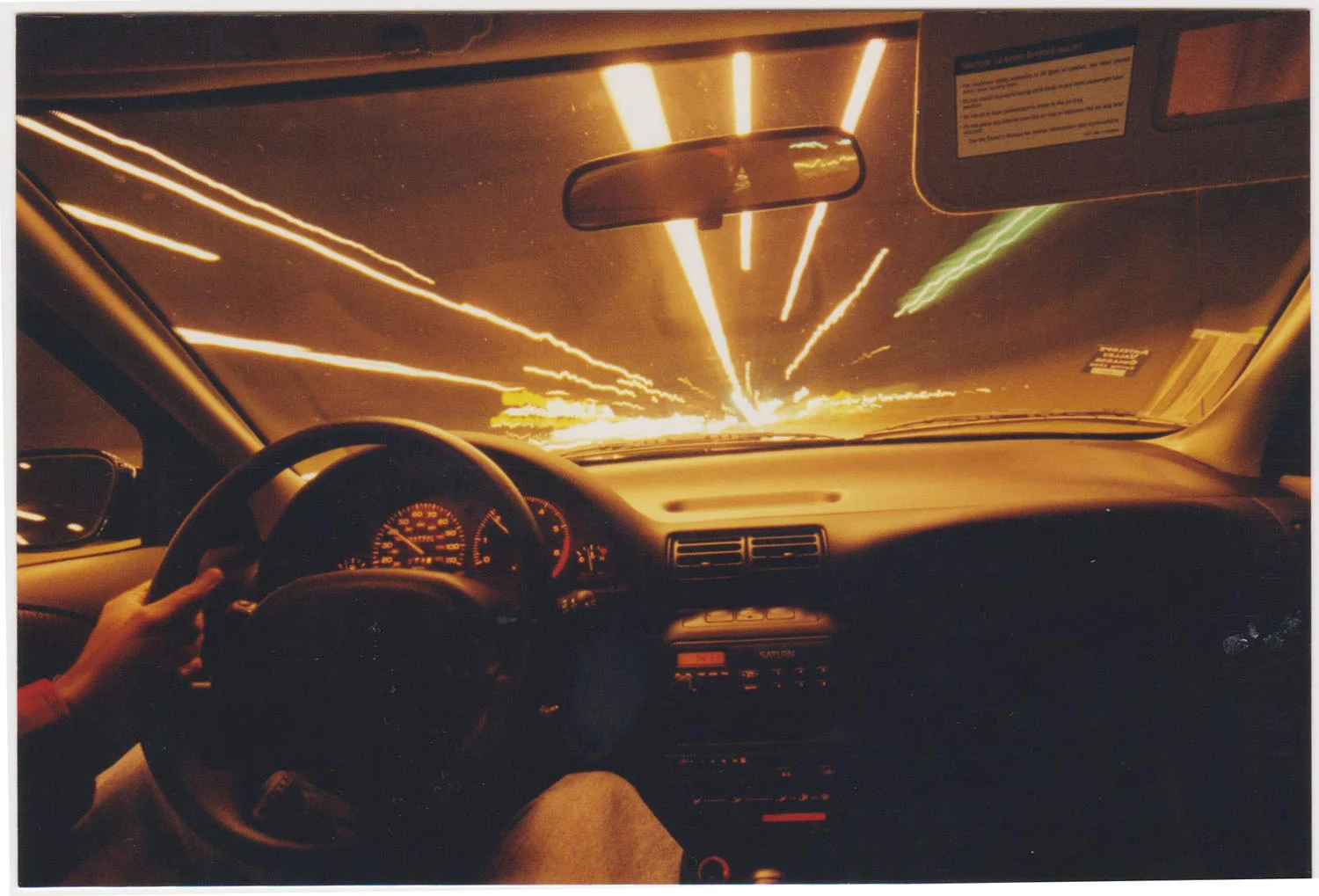

Consistently in these photographs, there was a steady decline in the occurrence of more classic, traditional celebrations. Popular early snapshot themes like the first day of school, the recording of one's first car, or even a "selfie" with a trophy animal, were gradually replaced by a new kind of uninhibited self-exploration, moving towards the increasingly narcissistic behavior prevalent today on Instagram and other social media. People got drunk in their cars and took photos. They photographed their friends and siblings in intentionally unflattering ways, blew clouds cigarette smoke into the lens. They flipped off their siblings as they photographed them, letting the flash illuminate their blurry middle finger in the forefront of the frame.

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

In many ways, according to Jackson, the 4 x 6 borderless photos marked the end of an era for the snapshot being about the documentation of shared memories and experiences among family and friends. It has evolved into online sharing of photo images to mainly strangers, and Facebook “friends.” One’s photos began and continue to exist on a larger stage in front of the floating gaze of the outside world with all of its attendant “likes,” hate filled comments, and a constant desire for virtual approval. "Associated with this desire to share with a larger, more critical and discerning audience," he says of today's era of social sharing, "the photos of our current age have become carefully curated to induce envy in the viewer.” There is also a corresponding caution in what is being photographed due to an image’s ability to go “viral” and its ubiquity across social media. In retrospect, the 4 x 6 borderless photo represented the end of an age of documenting one’s life in all its messy and funny details. Now photos serve to highlight one’s lifestyle in a carefully calibrated quest for validation.

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

Image courtesy of the collection of Robert E. Jackson

A selection of images from Jackson's 4 x 6 collection + photo paper