For nearly two decades, Seattle-based Robert E. Jackson has collected more than eleven thousand American snapshot photographs from the late 19th century though the late 1970's, and has been exhibited throughout the United States, including the National Gallery in Washington, DC in 2007, the Amon Carter Museum in Texas, the Los Angeles gallery Ambach & Rice, and at Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York City in 2013 with the show "Snap Noir: Snapshots From the Collection of Robert E. Jackson". Selections of his collection are regularly posted to his Instagram account and are well worth following.

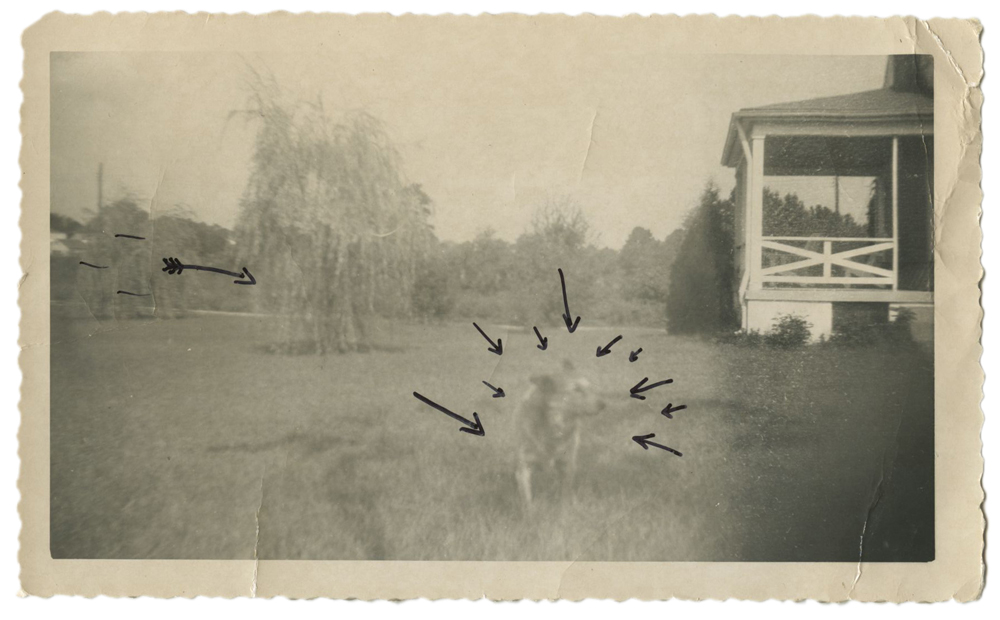

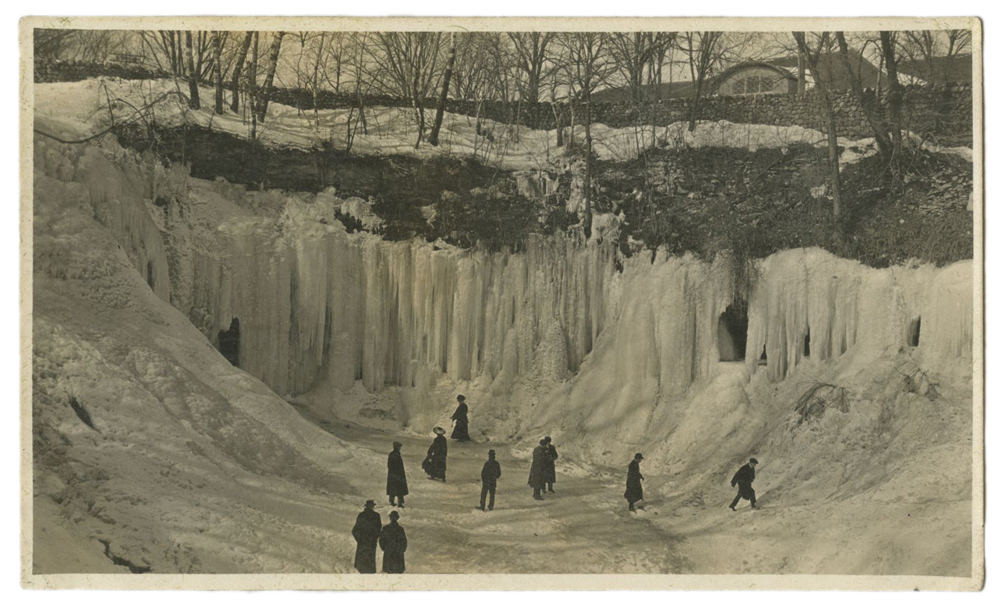

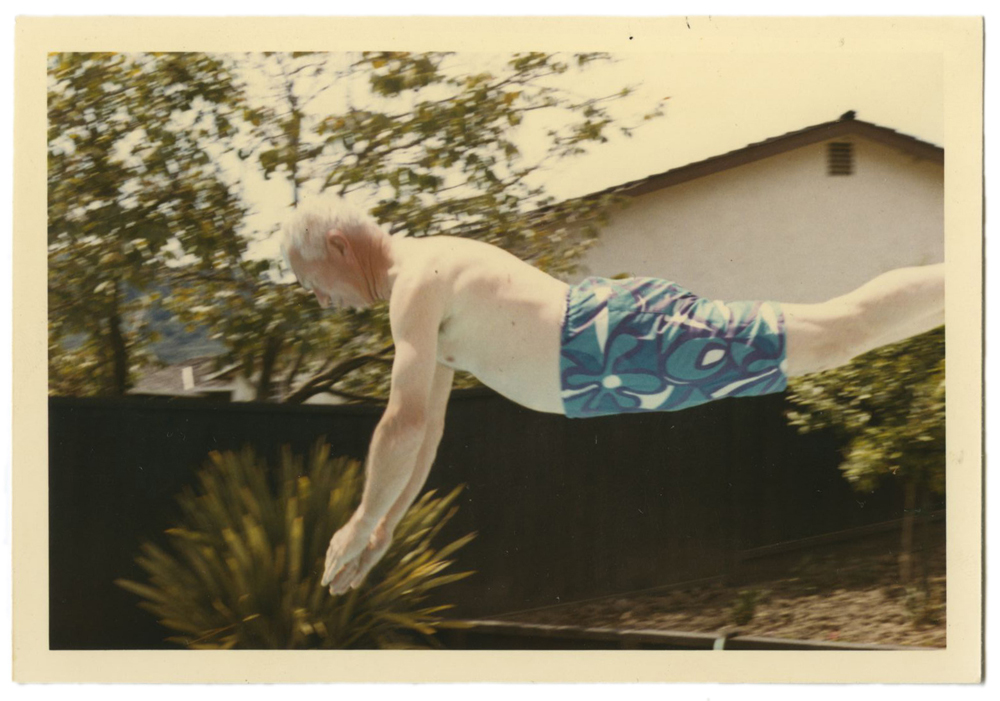

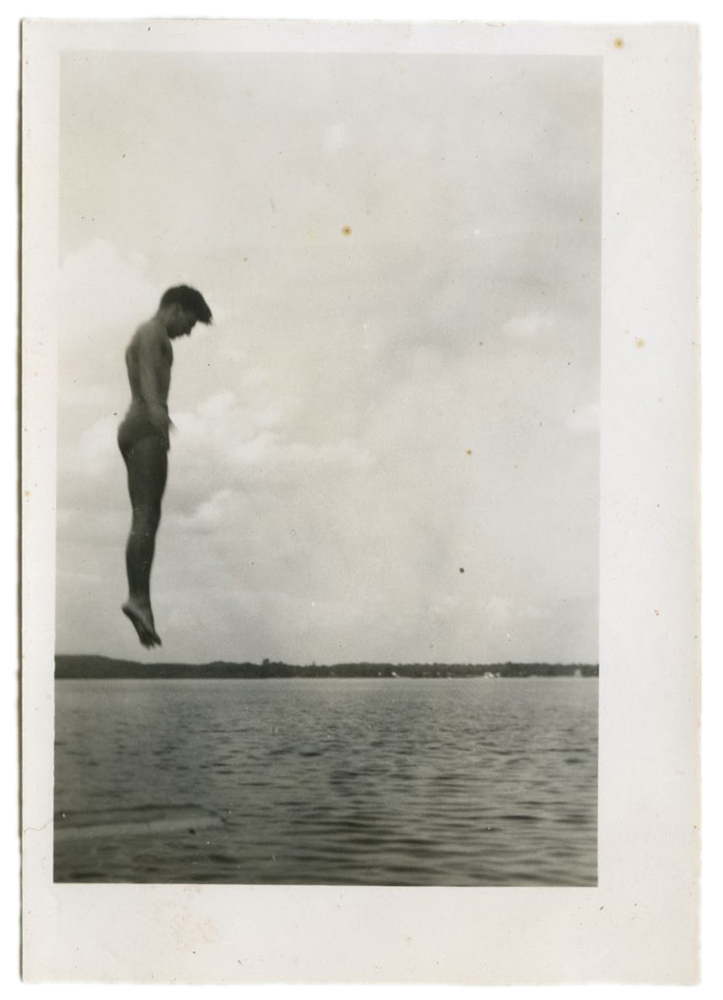

Jackson's practice lies somewhere between collector and curator, one that hinges on the photographs' anonymity and on his attention to their unique formal and aesthetic qualities. The photographs often lack dates, authors or titles, and in turn, Jackson is concerned less with the people who took the photos, their grand or individual stories, or where and when the photo was taken, and more with their pure photographic power. While popularized books like "Awkward Family Photos," and countless Buzzfeed posts celebrate the humor of snapshot photography with an often cheap-feeling irony, Jackson takes a deeper interest in exploring how the discarded moments of the vernacular past can serve as a form of unintentional art. His attention to magical accidents - lens flares, curious framing choices, and themes recurring across the images various anonymous authors, elevate each image beyond their original intended purpose.

I recently spent some time with Mr. Jackson, learning more about his practice while looking at the collection, which is organized in intimate albums in his Seattle apartment.

Jon Feinstein: Do you see yourself as being more of a collector or "curator?" Are these distinctions important?

Robert E. Jackson: I am a collector first, then a curator of that which I collect. When you collect photography you wish to make visual sense of what is out there to collect; to understand the wide variety of imagery which exists in the snapshot medium. Once you have amassed the material, you begin to see patterns emerging in the photos collected and you begin to put them in categories and think of various thematic ways they can be viewed. That is where the curatorial impulse starts to come to the fore. Plus by seeing like material together you begin to make value judgments about what is good versus not so good. And at that point, you may eliminate certain images from the collection. Curation is about choice and selection. It is as much about what you decide to reject as it is about what you decide to keep.

JF: The original context of the photographs in your collection is rarely, if ever important. Like Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan's "Evidence," what's striking is how images are paired together. Why is context irrelevant to you?

RJ: Because for me as a collector, it is all about the image. I am not (for the most part) a subject driven collector. I am an aesthetic based one. I am a formalist in terms of my eye, not an historicist.

JF: In your years of collecting, what aesthetic details and/or formal elements have you have been drawn to most consistently?

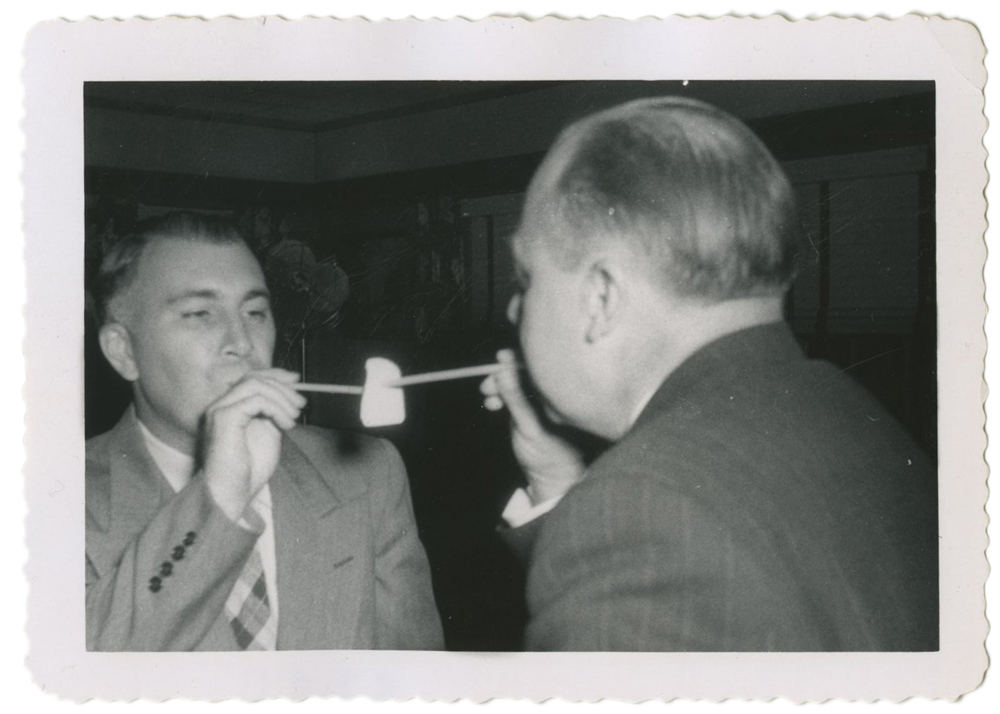

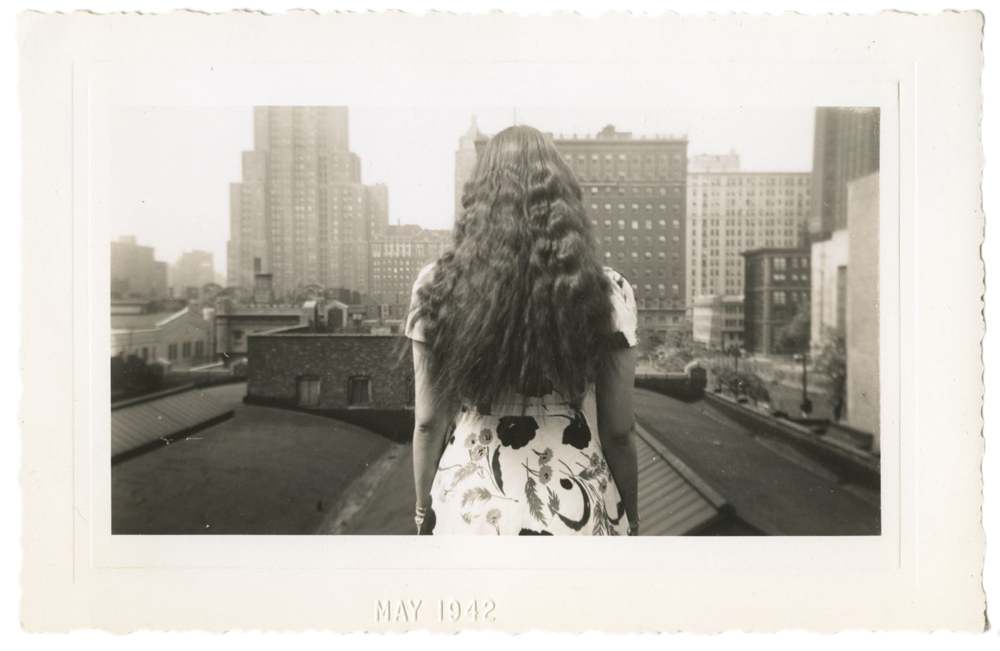

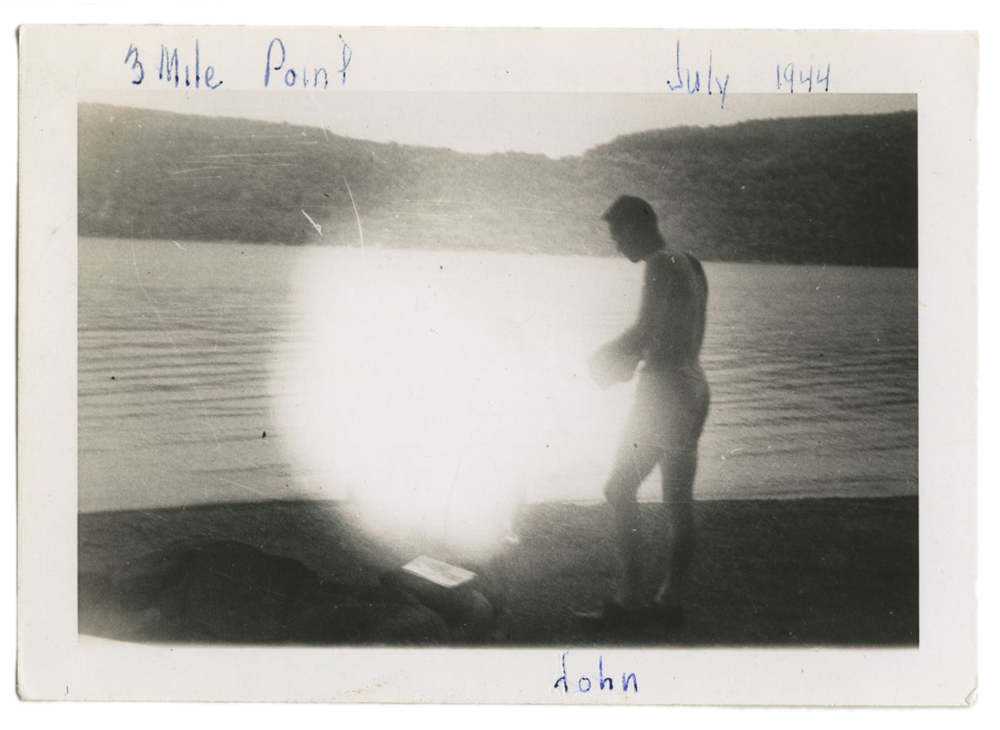

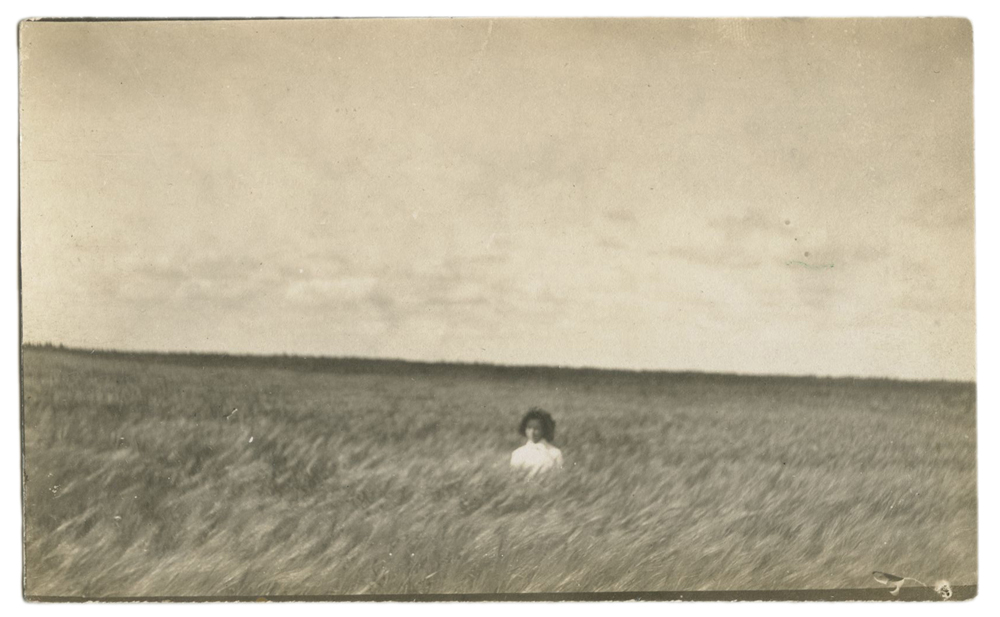

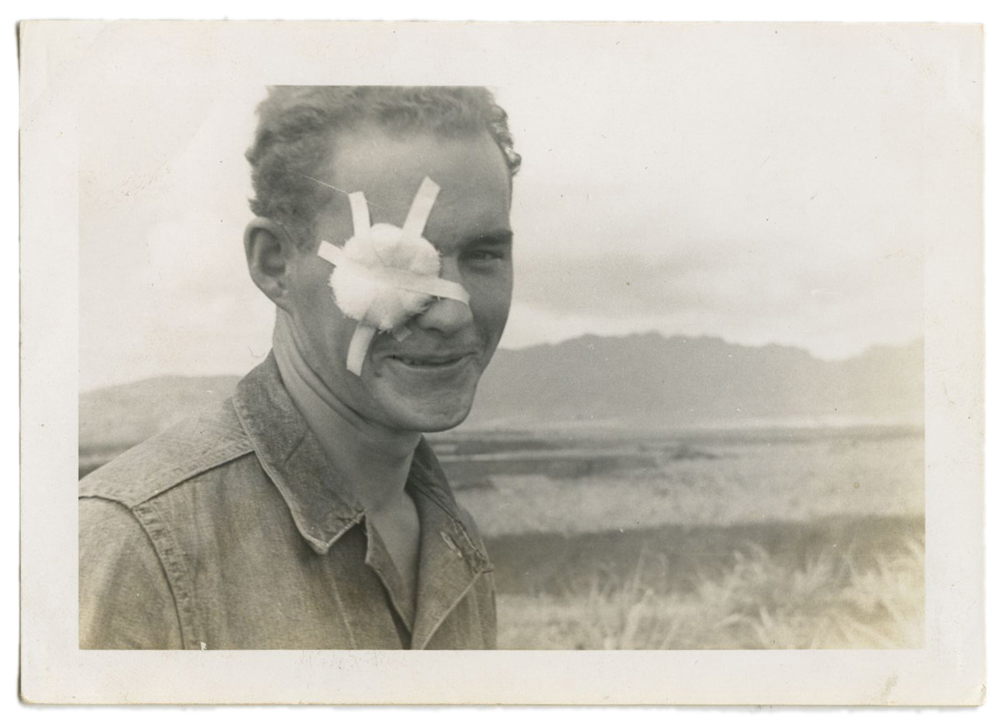

RJ: I generally look for a photo which has an immediate strong visual impact. I like photos which play with the notion of what is a snapshot. Photos which are dark or have a film noir quality. Photos which have an underlying mystery to them.

JF: Most of your images are purchased from auctions, Ebay, Etsy etc. Did you initially rummage through bins at at yard sales etc? Do you continue to?

RJ: I generally did not. It is my belief that if a bin or box is there to go through, it already has been by someone before me and I like to view fresh material. I also purchase a lot of my material directly from dealers and collectors at their house or storage area where their material is in boxes, etc. It is in that context whereby I will “rummage” through the photos.

JF: Over the past couple decades, there has been a revived pop-cultural interest in the snapshot. I'm thinking of magazines like Found, and Urban Outfitters style books like "Awkward Family Photos," as well as viral fascinations with decontextualized stock photos. Does this impact your practice or how you think about collecting vernacular imagery?

RJ: The references you cite deal with the kitschy (and often cute) aspect of snapshot imagery. They deal with the “funny” or, in the case of stock imagery, with the “pretty” or perfect shot. I want to dig deeper than that into what the snapshot tells me about the human condition about the nature of the medium and the photo process mistakes that can occur. Most people, when they think of snapshots, think of the kinds of things which make it into the pop-culture realm. Images which would work well on a greeting card. But the snapshot is much, much more than that. The snapshot is a very malleable object.

JF: What do you think your collection reveals about the human condition and/or the nature of the medium.

RJ: I feel that snapshots can get close to capturing the essence of humanity. They deal with the unspoken and unnamed. They often emphasize the aloneness and alienation and underlying sadness of life. But snapshots can also evoke the ineffable joy of life. They are often the visual poetry of the human condition. And there is always an undercurrent of bitter sweetness as they were taken to be a surrogate for memory. At the same time, I think they emphasize how much we need to establish a sense of belonging in this world. How we need to communicate to the world that we are here-that we are standing next to our new car, our new house, our fish catch. What I call photography as “trophy-ism”. That we were actually at the Eiffel Tower, that we did climb this mountain or made it to the top of this rock. We make sure we photograph ourselves on towers and bridges, and poles and tree stumps to say “look at me, I did this.” "Look at me—I did exist." That is what snapshots tell us. And by looking at these photos and by participating ourselves in the photographic act (via selfies, and Instagram, and posting photos on Facebook), we all feel a part of this shared human experience.

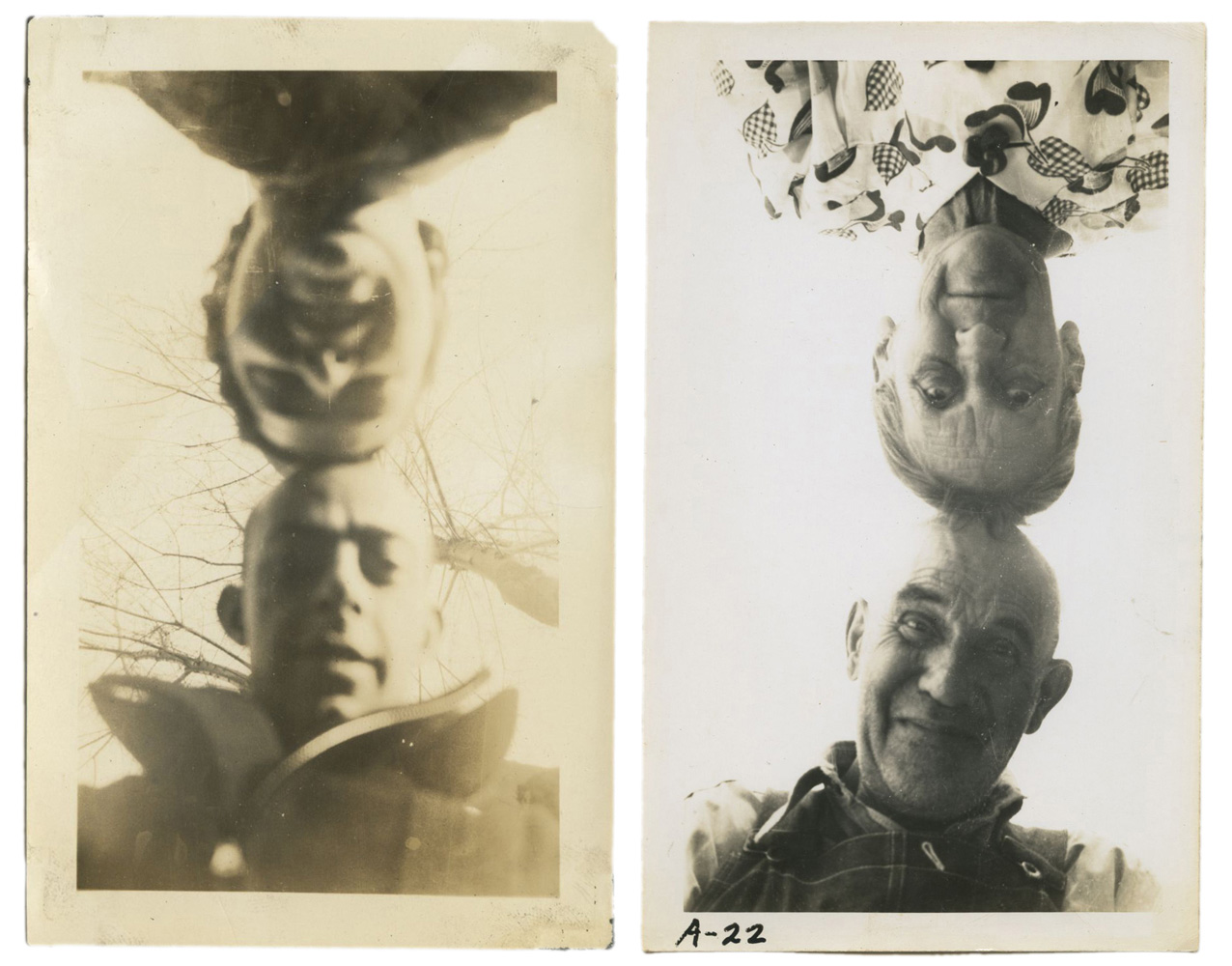

Plus I mentioned before that photography is a very malleable medium. When you get enough photos amassed, you can start to see patterns emerge or you can start to make up patterns. Like what rooms are the most common rooms for snapshots to be taken, how there are more vertical snapshots than horizontals, on what side of a woman a man generally stands when a photo of the couple is being photographed, etc. There are many, many ways to look at a photo: historical, aesthetic, sociological, formalistic. You can concentrate on the cars, the fashions, the hairdos, the gender mix, the seemingly “gay” subtext, the border around the photo, the caption on the front or back, what is going on behind the subject of the photo, the weathering of the photo due to it being in a wallet, the camera mistakes evident in the photo (emulsion issues, light flares, double exposures), whether the photo has been hand-tinted or drawn or collaged on—there are all kinds of ways to approach and collect this most democratic of photo mediums. My collection touches on a number of these areas.

JF: Has the "digital age" changed the way you think about collecting?

RJ: The digital age has opened up more areas for collecting (and avenues for buying photos) and for ways to communicate with fellow collectors. Plus there is so much more one can do to organize and catalogue a collection now that you can store your files digitally

JF: How do you feel about Instagram? In a few decades, is it possible we'll look at it and other digital "vernacular-isms" in a similar way to how you look at 20th century snapshots?

RJ: So much of digital photography is simply visual wallpaper. I am on Instagram (where I share snapshots from my collection, not snapshots I have taken with a phone). Instagram is part of the “me” culture we live in and like it or not I am part of that culture. Instagram is as much about the number of followers and “likes” which a site and photo gets as it is about the image itself. Photos on Instagram don’t generally deal in the messy aspects of photography—the mistakes, the sad times, the sense of loneliness and alienation. It is a curated life which is being created through photographs. It is an indictment of our 21st century visual narcissism and our wish to become some sort of digital celebrity with thousands and even millions of followers. I am always happy when I see that my posts have generated more followers. But in general, Instagram is not about a camera based impulse to document life, but a phone based mechanism to document lifestyle. Snapshots used to be something you would share with your family and friends. Now through Instagram you are sharing your images with mainly digital strangers.

JF: One of my favorite themes/ tropes in your collection are the "separated at birth" images. What's driving this selection / pairing process?

RJ: Oftentimes there is a visual resonance which exists when you view two like minded images together—something that doesn’t happen when you view a photo by itself.

JF: Does your idea of "pure photography" -- that certain "pure" vernacular snapshots can be read solely as aesthetic objects, apply to contemporary snapshots? To digital images/ iPhoneography...?

RJ: Contemporary snapshooters for the most part are interested in imagery which extols the narrative of “me”. Pure photography was a name I coined for those images which didn’t really fit into any category-which seemed to be abstract objects. They didn’t tell an obvious story. Often they were visual mistakes or anomalies. They could be blurred images, double exposures, etc. Social media photography isn’t about the mistakes, as they are easily deleted by the person taking the photo. Social media photography is about a highly controlled narrative of one’s life and lifestyle. I often like simply to appreciate the beauty of the photo as an object divorced from narrative and lifestyle—“pure” photographs allow me to do that.

JF: What draws you to a acquiring a snapshot? Does this differ now from when you started collecting?

RJ: I have to be visually excited by the image. It has to speak to me on a lot of different levels-my eye, my emotions, my gut. As you see more and more photos—you start to have a hunger for a kind of image which you haven’t seen before. You know it when you see it. Every photo I am offered by someone or which I encounter for possible purchase, I am visually processing through the lens of all of the other snapshots I have seen, rejected, or decided to call part of my collection.

JF: In 2013 you had an exhibition of your collection at Pace/McGill Gallery in NYC. How did the presentation (framing, white walls etc) change how the images were read?

RJ: The images were groupings. It is one thing to look at them in albums and to flip the page to see more. It is another thing to see them on the wall as an installation. There is a visual power in looking at the group as a whole which you don’t get from just holding them in your hand or looking at them on a computer screen. These were highly curated typological groups I put together.

JF: Do you have any upcoming publishing or exhibition plans for your collection?

RJ: No, nothing coming up. My real interest these days is trying to collect and promote my 19th century U.S. based cabinet card collection for a possible museum exhibition. Cabinet cards are an amazing area of photo history in which nothing much has been written. It is an area ripe for scholarship.

Bio: Robert E. Jackson has collected snapshots since 1997. In the fall of 2007, his collection was the subject of a show and catalogue entitled “The Art of the American Snapshot: 1888-1978” which was on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In early 2008, the show traveled to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. A second book featuring his collection was entitled “Pure Photography”. It was published in late 2011 by Ampersand Gallery & Fine Books in Portland, Oregon and included sixty images chosen by Jackson to embody the non-narrative aspect of snapshot photography. There was also an accompanying exhibition at Ampersand. In addition, over twenty of his photos were included in the 2011 bestselling young adult book “Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children” by Ransom Riggs. In October of 2012, Seattle based Marquand Books published photos from Jackson’s color snapshot collection in the book “The Seduction of Color”. The Los Angeles based gallery Ambach & Rice featured his collection in their December 2012 show “Lost & Found: Anonymous Photography in Reflection”. Approximately fifty snapshots from Jackson’s collection were paired with such photographers as Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Walker Evans and Catherine Opie. In June of 2013, Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York City featured his collection in a show entitled “Snap Noir: Snapshot Stories”. Jackson holds a MA degree in art history from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and a MBA from the University of Texas, Austin.