Three years ago, photographer Aaron Blum set out to make a series of photographs comparing portraits of Appalachians to Appalachian salamanders. Born in West Virginia, Blum was familiar with the terrain as home to one of the most diverse populations of the species, and envisioned that this might help him understand how geography and environment could influence regional identification. But he soon found this limiting, and his work evolved into his ongoing project A Guide to Folk Taxonomy, something much deeper than a literal comparison.

“That’s when I started thinking about all the other factors that formed Appalachians,” writes Blum, “and it became a constant echoing in my head, ‘What does it mean to be Appalachian?’ Blum quickly moved away from the curious amphibians to focus on how folklore and dialect shape its cultural identity. He briefly forayed into a typological approach, but quickly moved into an open-ended series of portraits and landscapes, one that Blum says “infuses Appalachian mystery with pseudo-scientific study, as well as personal experience as a lifetime Appalachian resident.” While Blum’s previous projects, namely “Born and Raised” are incredibly personal, A Guide to Folk Taxonomy works as a broader and more ambiguous representation of the region and its mysteries. Blum writes: “I wanted to find the factors that would explain Appalachia through the land and culture, and less through my family.”

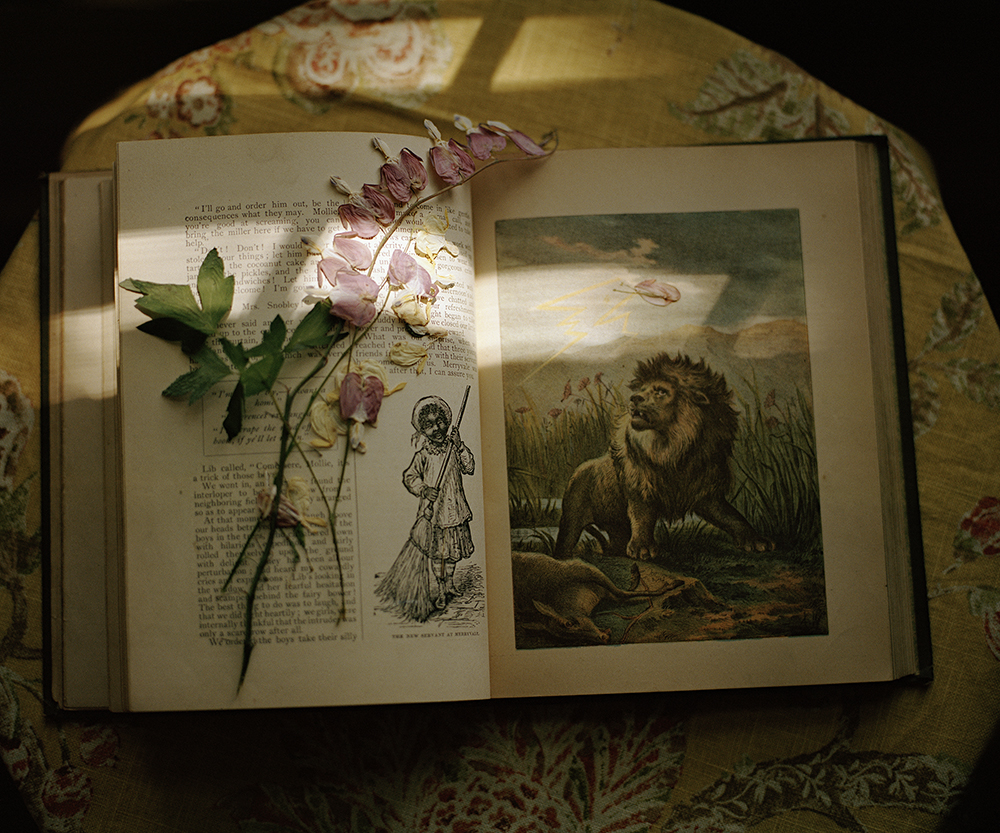

Blum avoids classifying his work as straightforward “documentary,” a tendency that he feels is common among many photographers working with similar subject matter. “There is a crushing kind of weight that comes with trying to represent a place accurately,” says Blum, who describes a desire “to use some type of disclaimer that yes this was somewhat a document, but it in no way was a full representation of anything, especially an entire culture, people, neighborhood etc…” While his pictures capture place, memory, and certain stereotypes that have developed about the region, and they are in many ways descriptive, there is something else at play. It’s a level of fabrication that hangs them in an ambiguous limbo between primary source, and staged narrative. Dimly lit portraits of his friends cast in haunting light are shown beside pictures of dead birds that reference omens of Appalachian folktales. They are moody, dark, and even gothic– qualities that one might not traditionally associate with documentary practice. “Personally many of my images are set up using memories, past occurrences and stereotypes as the catalyst for the content,” says Blum. “So often they are not in the moment, but they are very truthful.”

These layers of ambiguity are central to establishing Blum’s unique style of narrative. He sees Appalachian mythology as something that, while rooted in the past, is a determining factor in shaping modern Appalachia. While he avoids clichés of people “sitting around a campfire spinning cautionary tales” he’s interested in how it can serve to explain the unknown, and in turn, can have a significant impact in shaping heritage. “Storytelling is a birthright,” says Blum. “It’s an innate human characteristic to see something and want to be able to communicate it to others, but at the same time have a unique way of describing it. That’s why I was so interested in it. It’s a way of preservation, and its part of what makes us who we are.”

Bio: Aaron Blum is a proud eighth-generation Scots-Irish Appalachian from the mountains of West Virginia who has lived in Pittsburgh since 2010. He has always been aware of the views that others hold of his home, and his artwork is a product of his exploration of what it means to be Appalachian. After graduating with degrees in photography from West Virginia University and Syracuse University, Aaron immediately began receiving recognition for his work including the Juror’s Choice Award at Center: Santa Fe, Critical Mass top 50, and an Emerging Artist Honorable Mention from the Magenta Foundation. His work has been featured by Fraction Magazine, CNN, BBC and Aint-Bad among others and is in the permanent collection at both the Haggerty Museum of Art and the Houston Museum of Fine Art.