Posts like these are tricky. Every year, a growing number of MFA photo programs across the country churn out ripe, excited graduates, ready to seek their fortune in a rapidly evolving art market. Some will use their new relationships and refined smarts to stake claim on the art world, while tastemakers and opportunists alike try to predict who’s “hot,” much like taking bids on Etsy or Shake Shack’s recent public offerings. But what excites us most about this year’s ICP-Bard MFA graduates is their commitment to a range of photographic methods. Their work is hip yet thoughtful, and is consistent while rarely exuding a particularly "ICP-Bard" aesthetic. They continue to blur rigid categories, incorporating both process-heavy and straightforward documentary traditions, sometimes in the same series. Without further ado, we've culled together a selection of six standouts from ICP/Bard’s MFA class of 2015.

Joseph Desler Costa, who exhibited earlier this year in Radical Color at Newspace Center for Photography in Portland and Humble online, photographs mass produced objects including handguns, beer cans, cars and electric guitars, and re-contextualizes them as uncanny, hyper stylized forms. While they fit comfortably with the eye candy of many trendy new-still-life photographers, their realizations go significantly deeper than their initial intake. “Our temporal experiences,” writes Desler Costa, “exist in a state of constant flux, shifting between a physical reality and the seduction and distraction of the more desirable alternatives forever available to us. ”

Marie Louise Omme assembles photographs of commonplace objects into fragmented displays that draw relationships where you might least expect them. In one image, an iPhone sits on an otherwise empty bed, ghosted by a ray of light while covered in a pile of mysterious sand. Another image depicts a Greco-roman bust shot through a store window, back facing the photographer whose shadow looms below it. A third photograph blasts an abstract collage of bright, pastel paper and nondescript foliage with a studio strobe. The discordance of these images is uniquely inviting, drawing attention to ordinary phenomenon that might otherwise go unnoticed.

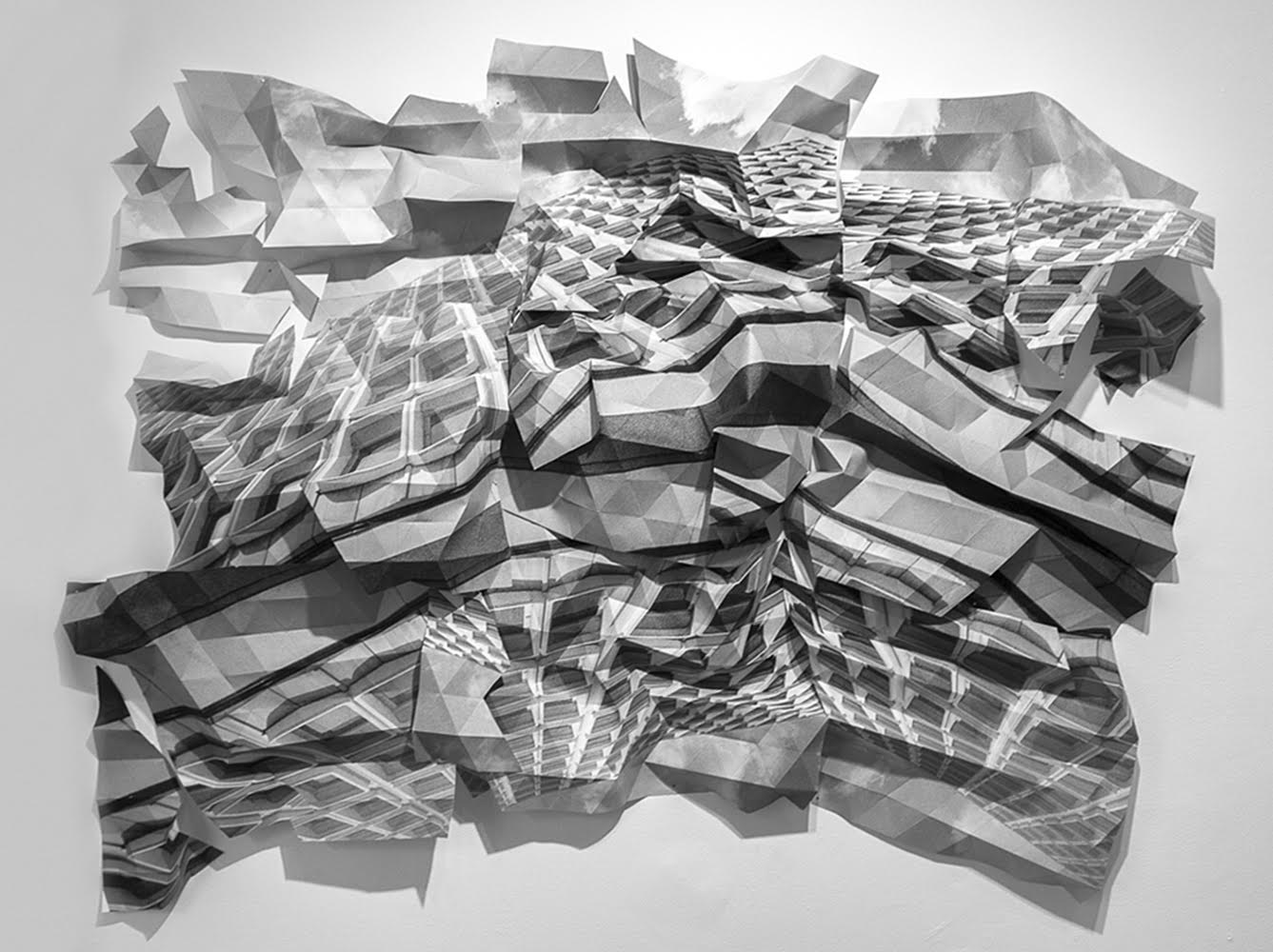

Jessica Thalmann’s Fold (Un)fold is an interdisciplinary exhibition using folded photographs, comics, concrete sculptures and a two channel video installations to address how the flat photographic surface can be manipulated to expand our understanding of history, time and space, as well as political and personal trauma. "The project is surprisingly personal in nature," writes Thalmann, "as I focused primarily on a shooting that occurred in 1992 at Concordia University where my uncle, Phiovos Ziogas, was a professor killed during the massacre." Giving historical and political weight to recent conversations about photographic process, Thalmann explored the event's impact on her family by photographing the building where the shooting occurred and folding the prints into three dimensional, sculptural forms. "In a plane of a photograph," says Thalmann, "you can fold one event from the past into the future."

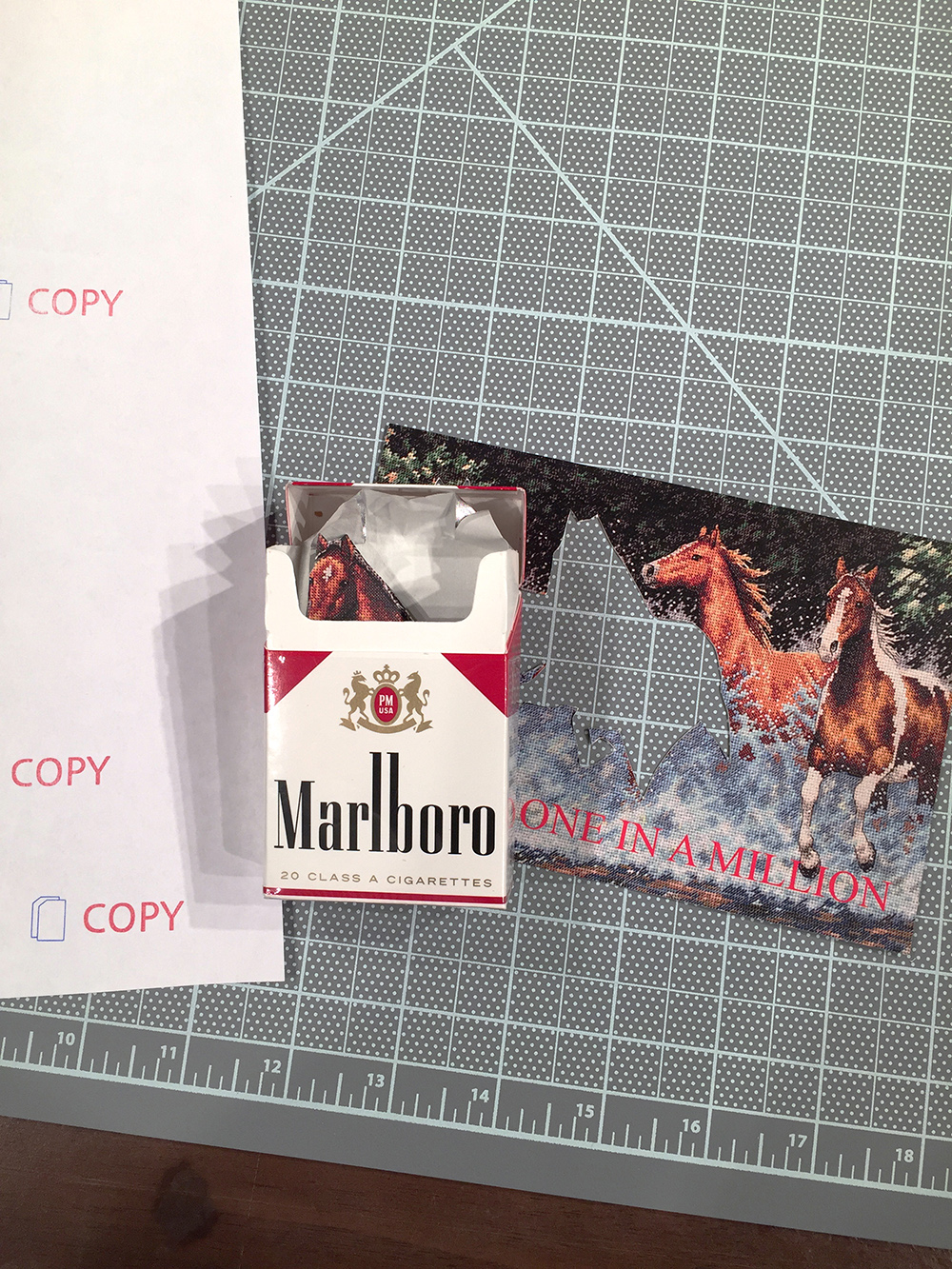

Daniel Terna uses video and photography to question the motivations for making pictures, historically and today. He breaks from “linear” narrative structures, jumbling found still lifes, environmental shots and occasional voyeuristic moments that peer into the strange and idiosyncratic nature of the everyday. “I look at things that require permission to be accessed or that have barriers in place,” writes Terna, “and even if I lack clearance, I’ll amble along, pretending to belong. Within these circumstances, I look for the silence that follows a badly-told joke, when the uttered words are still lingering in the air.”

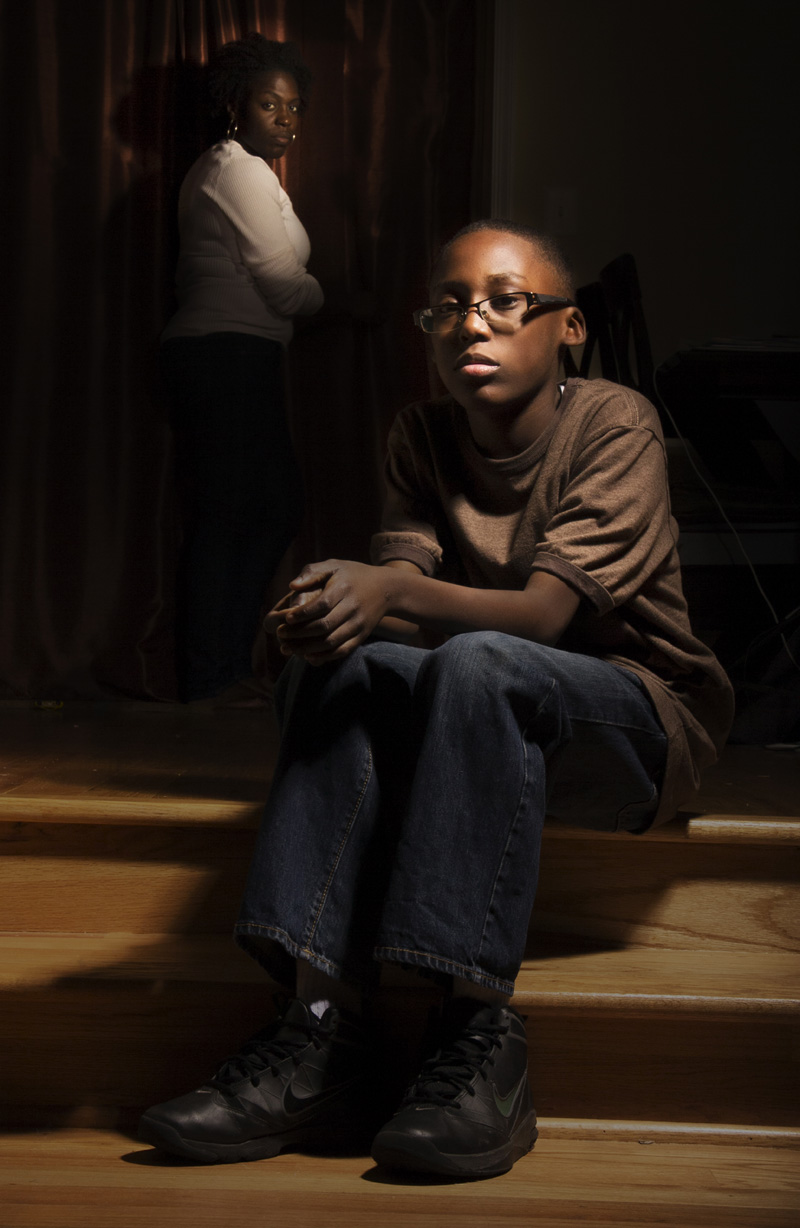

Kimberly Wade’s Red Maple is a series of photographs of her fourteen-year old son, tracking his physical and emotional development. Unlike Nicholas Nixon, or Rineke Dijkstra’s serialized portraits of transition, Wade takes an intimate, documentary approach that is more about emotional charge than typological observation. For example, Wade describes how her son seemed more open to being photographed and making eye contact with the camera when he was younger, and has become increasingly distant as he ages. She combines images that are as quiet and endearing as they are goofy and gangly, creating a visual story that captures a complex and incredibly layered path to adulthood. The images’ impact relies on their ability to straddle the line between personal and reportage. "I guess I do lean towards calling it documentary," writes Wade, "but with more of a psychological twist to it. I also see it as an investigative tool, helping me to analyze this seemingly drastically changing moment in our lives."

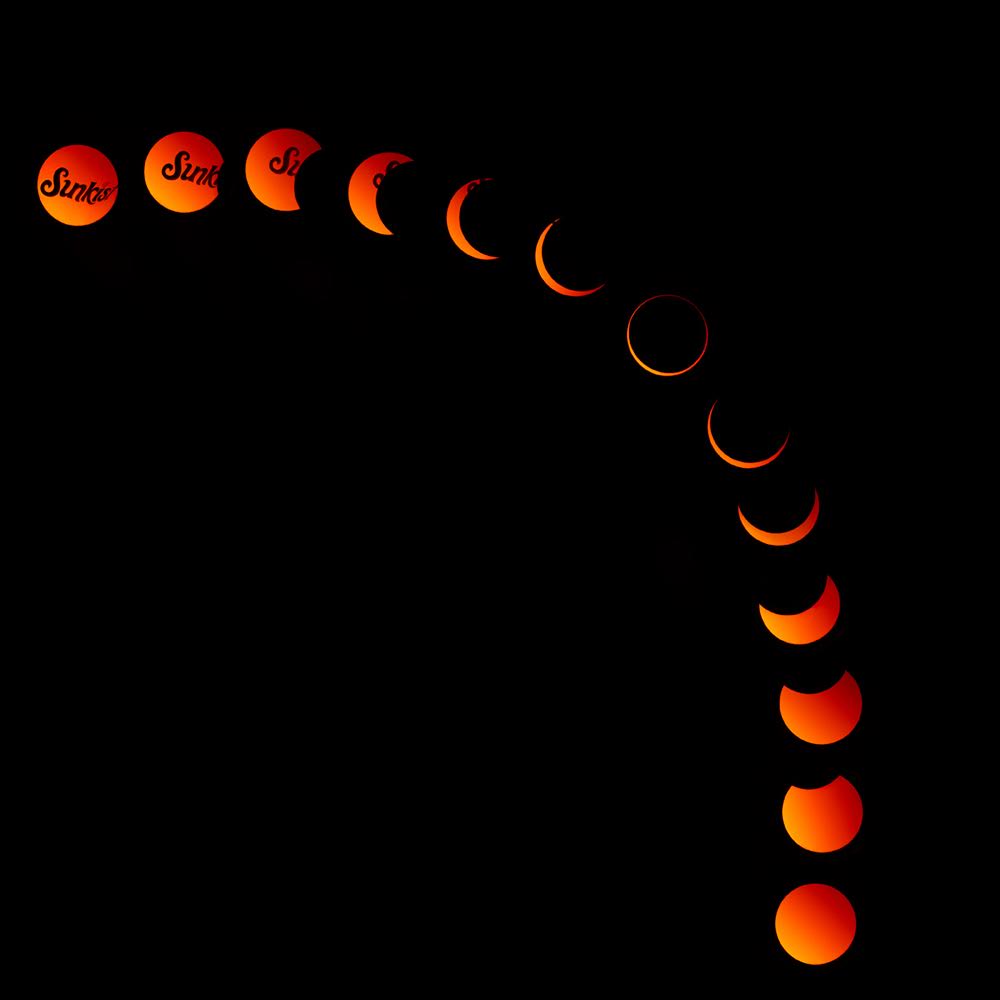

Beau Torres describes his work as hinging on apophenia, an experience of perceiving patterns or relationships in random or presumably meaningless data. This plays out in his appropriately titled When Things Come Together, a series of photographs made in Atlanta and New York City. He shoots with an i-Phone, and a date-stamped 35mm film camera from his childhood, using the “straight” language of street and 1970’s color snapshot photography to comment on fashionable tropes in contemporary still life photography and online culture. “The construction of these images comes from the frustration of not making decent digital collages in Photoshop,” writes Torres. “As hard as I try they just end up looking like bad GeoCities design, and that’s saying something.” Instead of letting this get in his way, Torres takes what he likes from traditional and "new" photographic genres, creating what he describes as his own hybrid philosophy. “It was more exciting and rewarding,” writes Torres, “to create this kind of cut and paste collage work in the field than what I was working with in the studio environment.”