© Josh Poehlein

The first image Seattle-based photographer Josh Poehlein made for his series Hinterland is a vertical photograph of people walking up a barren sand dune. One of the few images in the series that contains a human presence, it suggests a journey into an unknown void, an infinite, open-ended reality, and in some ways serves as a linchpin for the entire project. The work, a mix of sculpture and studio-based photographs of stars, interstellar abstractions, and natural phenomena paired with images of the Pacific Northwest’s sweeping natural landscapes, raises questions about time, space, and photography’s ability to reconcile it all.

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

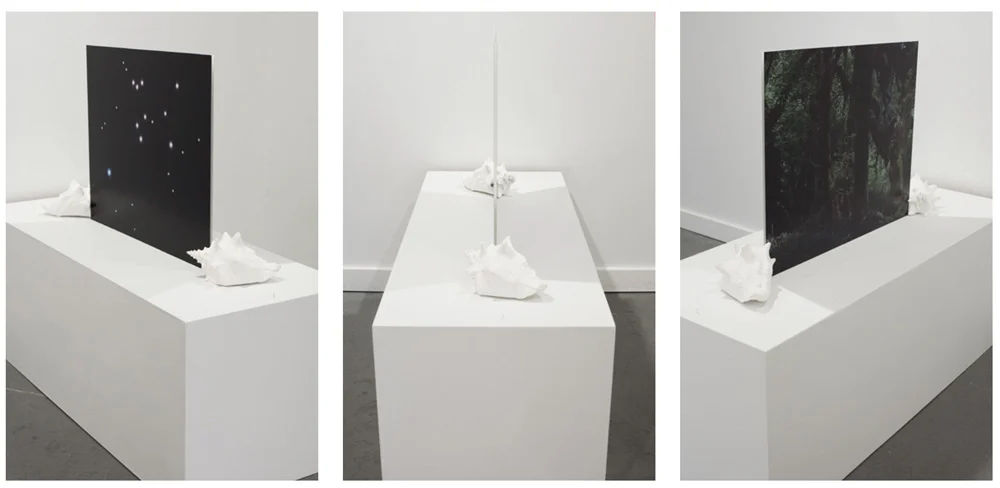

Scale and physical material are crucial to Hinterland’s metaphors, specifically with regard to the treatment of photography as a physical form. When working at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography during graduate school, Poehlein handled thousands of photographs for over fifteen large-scale exhibitions, and was intrigued by a general desire to minimize their physical qualities. “Photographs are often extremely heavy, fragile, difficult to hold, and rarely totally flat,” says Poehlein. “Even so, many of the display techniques seek to minimize these physical truths.” Poehlein’s questioning of what he saw as a tendency to set aside its physicality and object-ness inspired him to think more deeply about the images he made, and how he might eventually exhibit them to alter their tactile possibilities. He's toyed with various presentation methods including un-framed, double-sided prints bookended by plaster cast sea shells, and images paired with ambient audio clips on his website (when you visit his site, turn your sound on.)

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

As he made new work for the series, he began thinking more openly about how photography can exist in multiple dimensions beyond a flat print, or an image on screen. This plays a critical role in his conception of Hinterland and its relationship to science fiction and the unknown. “When you start to read about space travel and the prospect of interstellar communication,” says Poehlein, “you are confronted with these huge swaths of distance and time. My personal sense of time and space gets really compressed when compared to these concepts." For Poehlein, the medium's ability to simultaneously flatten and contain space and time is central to his work.

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

"When you think about time and distance on a universal scale," says Poehlein, "the Neanderthals might as well be our brothers and sisters.” Poehlein aims not to eliminate the flatness of the photograph entirely, but find a way to exhibit work that is both an image and an object. “I haven’t decided if that’s even possible to hold those two things in your mind simultaneously, or if they have to waffle back and forth between image and object.”

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

While his early love for science fiction stories like the Strugatsky Brothers’ Roadside Picnic and numerous Andrei Tarkovsky film adaptations are an inspiration for many of these pictures, he’s less interested in illustrating specific concepts, and instead uses them as open-ended ideas that can evolve as he makes new work. “This happens to the studio-based images especially,” says Poehlein, “because the first try usually doesn’t work out exactly how I plan it. I actually want to expand the story a bit, include some images that look like they are from the far future, not just the cosmos and the past.” This thought process aptly parallels his ideas about the ambiguity of time and its potential to fold in on itself. Hinterland's strength and power as a body of work lies in this constant fluctuation.

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

Recently, an incident surrounding a large-scale outdoor installation of one of his photographs in North Seattle’s Carkeek Park gave Poehlein new poise about his work’s multidimensionality and potential. As part of the park’s Heaven and Earth exhibition, Poehlein’s 7'x13' almost all-black photograph taken in the Ape Cave near Mount St. Helens was installed in Carkeek's shallow woods beside a walking path, intended to be enjoyed by onlookers and coexist with the natural elements as temporary public art. But within a week of its installation, strangers began tagging it.

© Josh Poehlein

“When it first got tagged I was initially upset because I put a lot of money and effort into putting the piece up, and it took less than a week to get tagged twice!” says Poehlein. “Once I calmed down I realized that it was making the piece way more interesting.” For Poehlein, the act of repeated vandalism added unforeseen performance-based elements to his practice, and a new layer to his ideas about the fluidity of time, photography’s ability to record it, and its parallels to primitive communication. “You have the forces that made the cave itself,” says Poehlein, “my photographing the cave, printing the image, and reinstalling it in a new natural environment, and then these people leaving their marks over time on the surface of the print. They are modern day cave paintings!”

© Josh Poehlein

© Josh Poehlein

Bio: Josh Poehlein is a visual artist based in Seattle, WA. He received his MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago in 2013, and his BFA from Rochester Institute of Technology in 2007. His work has been exhibited at the FotoMuseum in Antwerp, Belgium, the Les Rencontres D'arles Photographie in Arles, France, and in numerous group shows in the States and abroad.