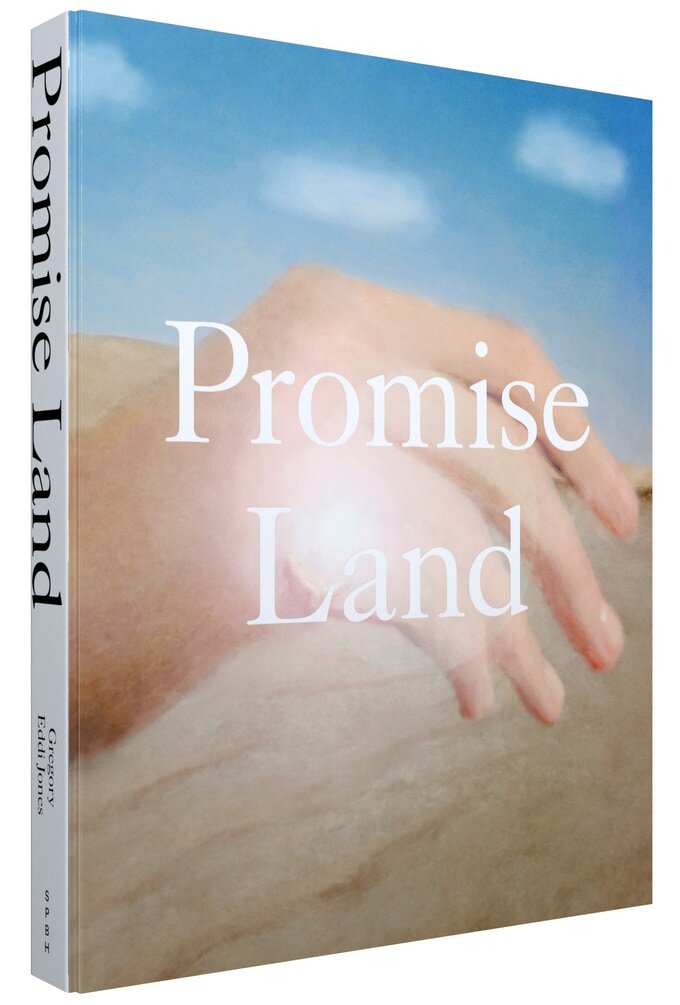

Gregory Eddi Jones is raising funds to publish his upcoming book Promise Land with Self Publish Be Happy and we think you should support it.

Promise Land is a 200-page, epic visual poem that reinterprets T.S. Eliot’s classic “The Waste Land” through a contemporary lens. Picking up where the poem left off nearly a century ago, Gregory Eddi Jones jacks and manipulates stock images and video stills, into unreal, sometimes cartoonish, sometimes pictorial riffs on the clichéd experiences they represent.

Chirping birds, boring cat photos, clouds, rainbows, and other dentist-office-poster images fade and break apart at varying degrees on the page, often looking like a marriage of classic impressionism and amateur “Microsoft-paint-ism”…. and that’s precisely the point.

For Jones, the cheapness of these photographic conventions and how he treats them reflect what he considers the “spiritual poverty of common cultural pictures.” En masse, they envision photography’s potential to do more than just regurgitate a simulation of these base experiences.

Nearing the end of his Kickstarter campaign (hey readers, you should help fund this!) I caught up with Greg to learn more and wrap my head around his wild work…

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Gregory Eddi Jones

Betterland © Gregory Eddi Jones

Jon Feinstein: In your description of the book, you describe it as working toward reimagining what photography can be.... which I think is really true to all of your work. How does this specific project continue, depart, and build upon your trajectory with those ideas so far?

Gregory Eddi Jones: I realized maybe 7 years ago that the camera wasn’t the right tool to make the kinds of pictures I wanted to make. But I still specifically work within photographic conversations because I’m interested in both photography tradition and the massively complicated relationships that the medium has to truth and belief.

In many respects I think photography carries these relationships as burdens it can’t escape. There always exists a tension of seeing a picture and grappling with its representational acuity. I wanted to escape that burden and rip the guts out of how photographs are expected to perform.

Janus Horse in Motion © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: Where and what do you want photography to be?

Jones: I think what I want photography to be is a medium that always strives to be something different. Everything changes, as it should, and photography will continue to change as well because it is a technology-driven media. Photography is alive because it continues to change and shift and morph into new modes. Its evolution in only 170 odd years is a testament to its ability to adapt to changing conditions.

Photography is a bountiful garden that continues to sprout new and unexpected blooms. It’s a media of rejuvenation that changes with any new tool that’s introduced into its lexicon. I just want it to stay that way, which is to say I want it to never stay the same.

Suns set © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: Congrats on working with Self Publish, Be Happy. Since so many of our readers are in the dark about connecting with publishers, can you give us the behind-the-scenes on how you came to work with them?

Jones: I met Bruno initially back in 2014 at Visual Studies Workshop’s Photobook Symposium, where he had given an incredible presentation about Self Publish, Be Happy, its mission, and its history. I knew right away that if I ever published a book like this, he is who I would want to work with. Bruno has a long history of pushing boundaries, being playful, and forging his own path rather than following trends, which are all traits that I think I are in my own work.

When it came time to find a publisher for this work he was at the top of my list of people to approach, but I wasn’t exactly sure just how to do so. Last April, shortly after the world started to shut down with the initial pandemic surge, Bruno launched an online mentorship program and I immediately signed up thinking that at the very least he could help me develop the book further. After our initial conversation and after revising the book according to some of his suggestions, we started talking about the possibility of working together, and we’ve worked very closely over the past year to bring the book to fruition.

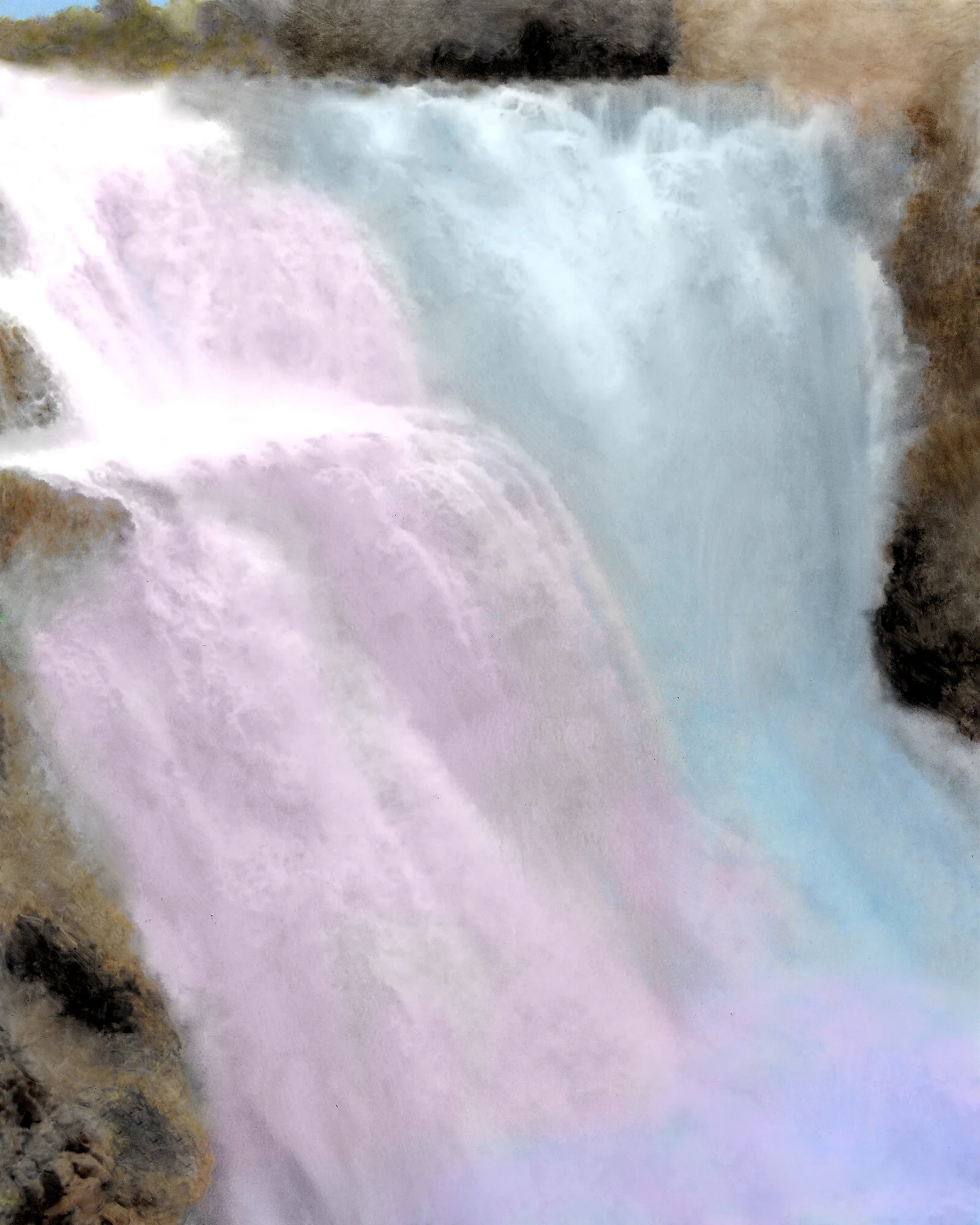

Lovers Falls © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: Getting back into the ideas behind the book, did you originally envision this as having a tie-in and riff off of T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land, or did that come further along in your process of making the work?

Jones: Eliot came early in the project for me. I made the first picture in May 2018, and I think it was in July that I had started reading The Waste Land. I really like making work that revisits old artistic conversations. I did that with Another Twenty-Six Gas Stations by looking to “update” the idea for a post 9/11 context. And I did that with Flowers for Donald by reclaiming old Dadaist strategies. And so, with Promise Land, I wanted the work to sort of pick up where The Waste Land left off, and much of the work tries to translate Eliot’s literary strategies into visual form.

Feinstein: Forgive me for the "who the f cares" question, but why "Promise" vs "Promised"

Jones: I chose “Promise” land and not “Promised” because photography is a medium largely used to create renditions of paradise. Most photographers strive to make pictures that are cleaner, more orderly, and more beautiful than actual lived experience. You mention “utopia” in your next question, and I think that the notion of utopian is something that’s secretly embedded in 99% of photographs we see on a regular basis. That’s certainly the case for advertising pictures, but even the casual ones we make on our phone.

How do we decide what to keep and what to delete? It’s a decision rooted in what imagery offers more of a promise to us in one way or another. We are all chasing ideals, and that pursuit manifests in all of our decisions, especially when we’re deciding what to make a picture of or what pictures to bring closer to our lives.

The Proposal © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: In a 2020 interview with Photoworks UK, you describe being "obsessed" with The Waste Land. What about it and why?

Jones: The Waste Land is a deeply layered ambitious poem, and it’s written in a way entangles so many old conversations. At its core is the myth of Camelot and the search for the Holy Grail, in which a sick king needed his knights to find the grail in order to restore his health and the health of his kingdom, which had fallen into ruin.

There’s a tragicness in the notion that a shiny gold magical cup can act as a keystone to transform the dystopic to the utopic. And what I think The Waste Land is about, in part, is pointing out the absurdity of that notion that the complications of human endeavors can be solved so simply. It’s rumination that humanity is incapable of being a good steward of itself.

The Actor © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: I understand that much of it is a commentary on the parallels between Eliot's commentary on the "loss of clarity" in social and political frameworks post WW2, vs late-Trump era USA. Where do you see this work sitting now that we've departed the chaos of Trump's presidency, but aren't quite en route to utopia?

Jones: Where we sit in this “post-donald” world is that the symptoms that gave rise to his cult of personality are not abetting. This sense of “post-truth” that we’ve been living through isn’t going away either. Culture continues to grow more fragmented, and old points of shared understanding are being pulled apart from ever-complicating social and political debates. To me, these pictures are things that emerge from those fault lines.

Dave #30 © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: You talk about this idea of "un-photograph"ing and release pictures from photography's traditional relationships to truth, belief, and idealism. Can you expand on this?

Jones: Most people’s first impressions of my work are that the pictures look like paintings, which is to say that don’t operate as photographs are expected to. Something that hasn’t changed in photography’s evolutions is its native signature of veracity, and I wanted to learn how to make a picture that could be released from this burden, and to operate on an entirely different plane of representation. The pictures I make don’t pretend to tell any sort of truth, the mind loses it’s need to verify them, which I think liberates them to operate much more freely as fictions.

Helen Going Home © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: A lot of what you’re doing with this, the Pictures Generation tackled decades ago, but clearly, you’re hitting it with a new, refreshing angle. How do you see your work building, expanding on that, making it new?

Jones: I felt very close to the legacy of the Pictures artists for a long time, and I think some of what they did as shaped my work pretty profoundly. But something that is a little unnerving to me is that the media critiques levied by Prince and Sherman and Heineken were utterly brilliant, but didn’t really change anything. We’re pummeled by wave after wave of media tropes and fantasies and they can be criticized, revealed, and turned inside out, but that doesn’t stop them. And I came to feel that any work I made specifically as a critique of an image-type like that felt inadequate. I’m not sure where that places me now. I’m starting to like the idea of making pictures in a non-critical framework. And I have questions about what pictures do uniquely.

Donut Heaven © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: Stock photography is a big resource for this work. Can you talk a bit about your process from what you were looking/ searching for/ search terms, to how you manipulated them, and the conceptual, societal implications and parallel's to The Waste Land?

Jones: What’s really interesting to me about stock photography is how important it is. These are pictures that represent common denominators of human experience, and idea expressions that are so simplistic they naturally perform as spaces of shared meaning. When social and cultural fabric is being pulled apart, I think it becomes even more important that we have something like stock pictures as a consistent presence in our lives. Because it’s spaces of shared meaning that hold different people together. This is why I think memes are fantastic. They work well to get everyone on the same page.

Island Tide © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: Does stock photography have the potential to go beyond these tropes?

Jones: I think that there’s a relationship that exists between stock photographs and mythological and religious belief systems. To some extent they serve a similar purpose. The way I use stock photographs in my work is as source material to create many different sorts of visual stories. I can make new characters and landscapes by sampling sections of different pictures and collaging them together. But I’m also interested in ripping the guts out of these kinds of common images and turning them into something new. In some sense I’m transforming spaces of shared meaning into far more ambiguous portals, in which everyone will see something different within. That’s my hope at least.

But in relation to The Waste Land, one of the most unique characteristics about the poem is that Eliot wrote it with many different voices overlapping and collaging together. It leaves the reader destabilized, because the narrator always seems to change. And so working with stock pictures made by many different people, different voices participating in different conversations, I think I’ve managed for the book to take on a similar quality in seeming like echoes of many different conversations colliding with one another.

Deputy Dog © Gregory Eddi Jones

Feinstein: As much as we want to “keep the discourse heavy” here, I want people reading this to be like "ok, I need to get this book." For our readers: sell us a little on it. You're crowdfunding thru Kickstarter - beyond just getting a mind blowing, 200-page book, what kind of rewards can people get by helping fund it?

Jones: Folks can pre-order a copy of the book of course. We’ve also made a special edition cover in an edition of 100 that doesn’t cost that much more. We also have a whole bunch of open-edition and limited edition prints at Kickstarter-only prices. People can also commission me to make a portrait of themselves or their loved ones (or their dog!). And we’ve given artists a chance to book a 45-minute portfolio review session with me as well. If successful, we’ll also hold a virtual event in September that contributors will receive an invitation to.

Feinstein: Awesome. Thanks so much for your time, Greg and good luck on the rest of the fundraiser!