© Will Douglas

Flat Pictures You Can Feel manipulates and repackages how we see (and feel!) images on screens, on walls, and in our hands.

Some of my favorite photographic series are ones that seep ambiguity. While I love typologies and projects with a clear beginning, middle, and end, pictures and sequences that at first bewilder me or make me think “What is this photographer actually thinking?" "What's going on in this image?" or ” Why are these photos organized like this?" often have the most staying power. Will Douglas’ latest book Flat Pictures You Can Feel, published earlier this year by Ain’t Bad, does just that.

Images of bullfights volley against religious iconography, photos of smashed surfaces, gravesites and others balancing soft and hard, peaceful and violent, immediate and metaphoric. Some are Douglas' own photographs, others are appropriated images from advertisements, rephotographed on walls or digital monitors. It's often unclear which are his own, and which are borrowed, but it doesn't really matter. The notion of "feeling," them, pulled from the book's title, is central to them all. Douglas collects and collates these haphazard moments into a strange meditation on how the process of viewing an image – whether it’s on a screen or in physical form – can change or even numb how we understand their place in the world.

After meeting Douglas at Portland, Oregon’s 2019 Photolucida portfolio reviews, I followed up to dig deeper into his ideas, process, and clarify the confusion that first drew me in.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Will Douglas

© Will Douglas

Jon Feinstein: “Flat Pictures You Can Feel.” I think I get it, but my mind still wanders in a million directions with this title. What’s the story behind it?

Will Douglas: Aint-Bad approached me about making a book while I was at a residency in Russia. I had started making an accumulation of images which was not meant to be a book, but rectangles on the wall (which later became FLAT PICTURES (YOU CAN FEEL)). I decided that the title needed to speak to what the book was as an object as well as to the content. It fluctuated between a few titles; the phrase FLAT PICTURES was for me an acknowledgment of the medium itself, the type of paper used in the book is very smooth, especially compared to the fiber paper which I had been exhibiting works on. The pictures I included are very much about the absence of depth. Images in the bullfight sequence have a little bit of pictorial space but are mostly flat. The inclusion of the phrase (YOU CAN FEEL) relates to the physicality of the book. You can touch these images--they do not hang in a gallery--but you can also feel them emotionally, using poetic notions and showcasing violence.

Feinstein: This is total non linear work. I feel like it could be rearranged infinitely, and while taking on a different meaning, still work. The narrative is disjointed but infinitely compelling.

Douglas: An immediate arrival at the end of the book is not essential at first. It is meant to disorient you. It is not an exhibition catalog. The narrative is there throughout most of my work. As I returned to strictly lens-based recording for this piece, I wanted It to have the sensation of installation and experimental narrative. I think it is important not to work in a wholly serialized manner when making pictures. Other mediums work well in this way; painting can speak loudly through mark making, but a photograph does not have this, so the mark needs to be made with image association and the corruption of fidelity to talk about physicality in relationship to digital space.

© Will Douglas

© Will Douglas

Feinstein: So much of this is about deep “looking”. Of course, all photography is, but I see it as a dialog about how we use photography to create narratives about products, gender identity, consumption etc. Where’s your head and heart in this?

Douglas: It is very much about looking. Most of my work is rooted in ideas of perception. I think it’s vital that the book is handled and looked through with the notation of orientation. By the time you finish the book, you will have tuned the book 360 degrees. The rotation is intended to make people break from their traditional experience with a book and experience the images in various orientations brining an embodied or performative aspect to interacting with the book. The pictures themselves are focused on religion, relic, and ritual. The history of religious imagery, icons, and mass reproduction of painting has a tie to photography’s history. The inclusion of the stain glass window of Mary serves as a device to reference the projected image.

Feinstein: The press release for the book uses the following language: “....photographs made in response to the ways in which spontaneous screen-based collage influences and complicates our perception of the 3-dimensional world.” Break this down for me.

Douglas: I believe our reception of images is overloaded. Image overload isn’t news, But I think it’s important to consider how the free association of images build in the subconscious like a collage. For example, a news story of Trump interacting with the US Mexico border intersects with what your ex-boyfriend ate on Instagram. The intersection fuses the quotidian with the monumental in a way that complicates how we deal with violence as well. Unexpected violence is why I included splices of the bullfight as a foreshadow to the sequence of images in the end. We frequently return from our screens to three-dimensional space. We have to deal with depth and physical relationships. After hours of staring at a small glowing screen I have experienced a distorted perception of space. The compressed space of the computer screen fundamentally changes the way I interact with and conceive of the three-dimensional world.

© Will Douglas

Feinstein: How do you go about selecting your sources for appropriated imagery?

Douglas: The book has many forms of images; I used medium format film, 35 mm film, digital stills, my video stills, rephotographed fashion advertisements, and video displays. I concentrated on treating the moving image in these public commercials as action in the real, the picture of hands with water repeated through the book, is a Dior video ad photographed from 50 ft away, this image was important as a religious gesture, there is also an image of apes from an old calendar in a window of a hardware store in Paris as a nod to evolution. Both images were photographed in the same city block as one another. It is important to me that I rephotograph the works to crop or intervene in some way, either it is a reflection in the glass of a storefront, a glitching monitor, or to change the fidelity of the image by altering the resolution form the original.

© Will Douglas

Feinstein: Speaking of appropriation, The Pictures Generation seem like an inescapable influence.

Douglas: The pictures generation is an influence. Of course, Richard Prince’s cowboys are in my thoughts. I use Prince as an example quite frequently while teaching. When learning about Prince’s Spiritual America, I felt that I could do whatever I wanted with images, that I was free to use or reuse the entire world and history of images treating them similarly to found objects.

Feinstein: You’ve also been working in sculpture, which I think is interesting given that so much of your work is about processing how flattening space - on screens etc.

Douglas: I started focusing on making sculptural works during graduate school at the University of South Florida. I always had an interest in making physical objects. I had worked manual labor for a living for a while (I still do), but it wasn’t until I went to Tampa that I started, including sculptural elements into my practice. It is important to me that we view works and discuss the interaction of the photograph in ways in which we encounter them. I do this by using construction materials but also putting photographs into situations we usually would not experience to render them strange. It is the material that the image interacts with that opens a dialogue about the multiplicity and reproducibility of a photograph that I have begun to push in the book as well.

© Will Douglas

© Will Douglas

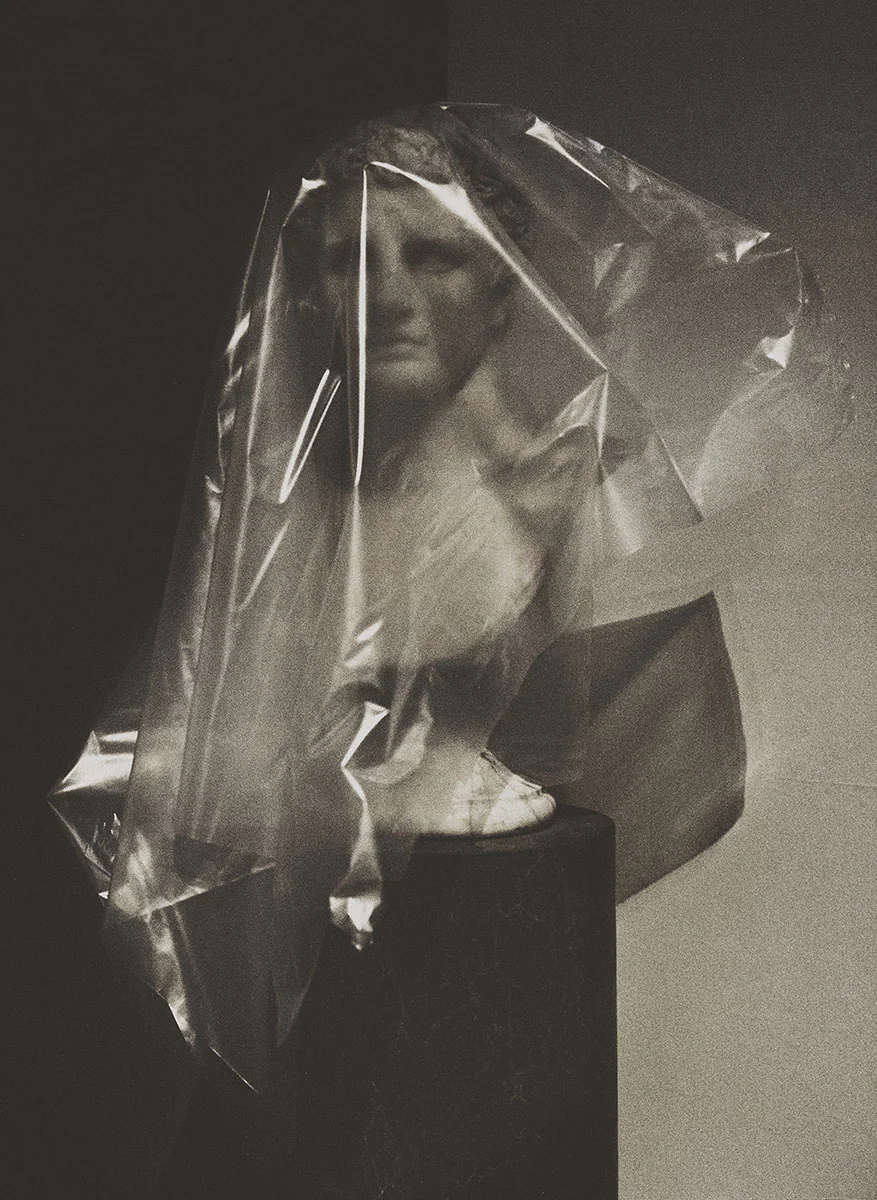

Feinstein: When we met at Photolucida, we talked about how this work also taps into tropes about male identity - specifically power and violence. Maybe even some subtle castration and emasculation themes in the mixx. The recurring bullfighter image. The shattered surface. The plastic draped male bust. The candles that - in this context - might have a tangentially phallic reference.

Douglas: Yes, the bullfight has been used in art history as a metaphor for masculinity, and its ritual is a stand-in for male violence and showmanship. The candle image is phallic and was made at Saint Estuche in Paris; it is titled for Keith, I lit a votive candle for Keith haring next to a piece he donated to the church because of their involvement in support of the AIDS activism.

Feinstein: How does this fit into the larger context of the book and your artistic practice ?

Douglas: The book investigates specific histories of religion and ritual. It looks at sculpture and its representation of the masculine figure in relationship to contemporary representation of figures. FP(YCF) looks at how we have created icons and present them two-dimensionally.

© Will Douglas

© Will Douglas

© Will Douglas

Feinstein: Does your own experience processing masculinity fit into this?

Douglas: The pictures were all made in Europe, specifically Paris, London, Madrid, and while I was in residence in St. Petersburg, RU then sequenced when I return to the states. The book is looking outward through a male experience while being conscious of the history of the gaze the camera has. The white male gaze and its history looking in on western cultures.

Feinstein: Do you see this work functioning differently in exhibition vs book form?

The book was made to be the book. No image was exhibited before publishing the work. It was meant to be an artwork in and of itself. I view the photos from the book as manipulatable individually. I am interested in repetition and recombination of images and so depending on the space in which the images will be shown and my thematic interests at the time the work can be recombined to address scale and the site specifically. I have recently shown works from the book in a solo exhibition at Tempus Projects in Tampa. The work was both rectangles on the wall, one with more of a sculptural gesture including a mirror, and as well as three porcelain vessels with photographic ceramic decals on each side. It is important to me to use this archive I have created for FLAT PICTURE (YOU CAN FEEL) to have a dialogue with the reverse process of flatting the world now that it is entering back into the gallery.