Los Héroes del Brillo © Federico Estol

Shine Heroes, a three-year project in which photographer Federico Estol worked with Bolivian shoe-shiners, frames resilience to social and economic discrimination as a foundation for solidarity.

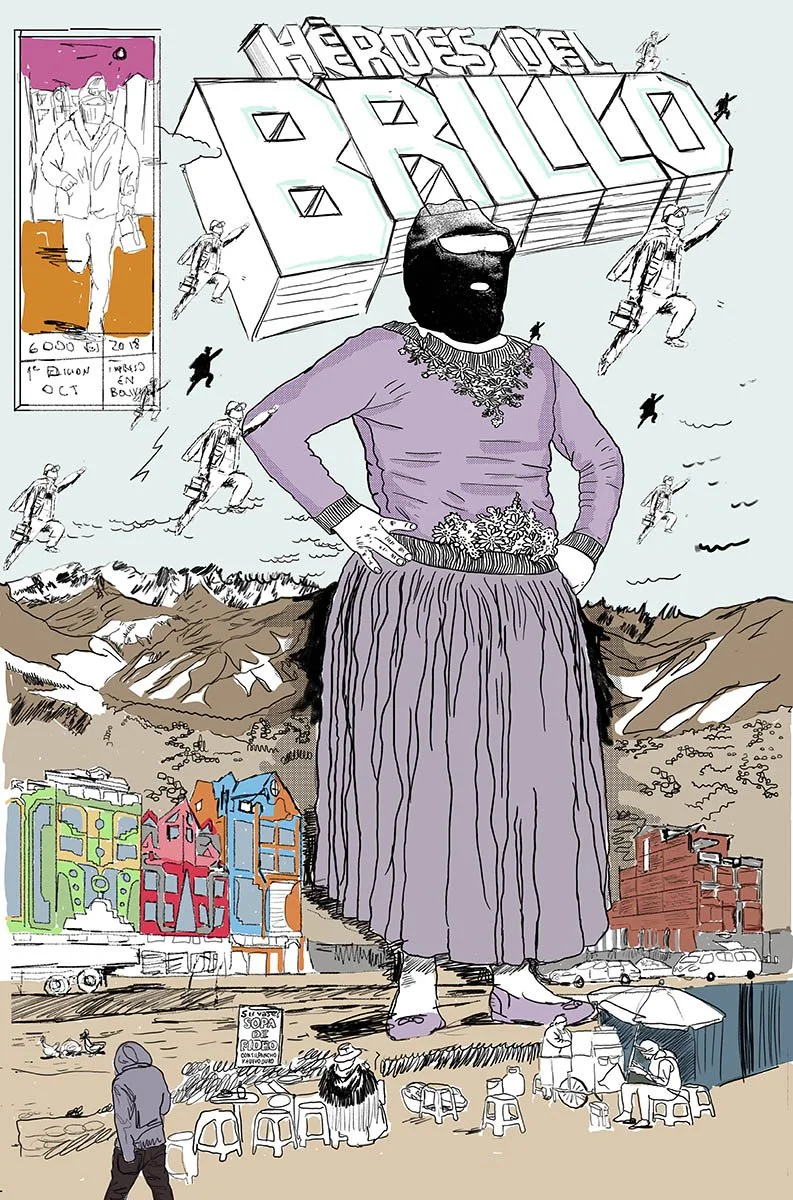

Federico Estol’s Los Héroes del Brillo, or “Shine Heroes” encapsulates the artist’s three-year collaboration with Bolivian shoe shiners living in La Paz and El Alto. The multigenerational urban tribe, as Estol describes them, scratches out a living while facing rampant social and economic discrimination. Ski masks, worn to protect their identities from family, friends, and strangers, mark them simultaneously as Other and as members of a marginalized economic class that typifies hustle.

Working with a local NGO that supports shoe shiners through newspaper sales, Estol organized a participatory workshop for shiners to visualize their stories. Drawing on the visual language of comic books and graphic novels, shoe-shiners portrayed themselves as heroes, not outcasts, whose work is both honorable and valuable.

Shine Heroes was recognized as an outstanding series and presented as the Critical Mass 2021 Exhibition at Portland’s Blue Sky Gallery earlier this year. Humble is pleased to highlight Estol as one of our ten standouts from the 2021 Critical Mass Top 50 finalists. See the others as we write about them HERE.

(PS - registration for Critical Mass 2022 opened July 7th! Click here for details on how to submit)

Federico Estol in conversation with Roula Seikaly

© Federico Estol

Hi Federico! It was a pleasure meeting you in Portland at PhotoLucida earlier this year. Thanks for speaking with me.

Seikaly: I’d like to start with how you learned about the Bolivian shoe shiners. What about this socio-economic phenomenon interests you?

Federico Estol: It came up over dinner when a family member told me about the situation of the shoe shiners of La Paz and the city of El Alto in Bolivia. I started my own investigation and found an amazing story of nearly three thousand shoe shiners that walk the streets daily in order to find clients. They are of all ages and over the last few years they have become a unique social phenomenon in the Bolivian capital.

This urban tribe is distinguished by wearing ski masks so they cannot be identified by acquaintances. The discrimination they face is fought with these masks; no one in their neighborhood knows what their job is. They hide it at school and even their own families think they have a different job when they go from El Alto to the city center.

They leave home as ordinary workers and store their tools and shoe polish at the associations where they have lunch and clean their hands before heading back home to El Alto.

I fell in love with the story and decided to explore the possibilities in January 2016.

© Federico Estol

Seikaly: I understand that you’ve partnered with Hormigón Armado, an NGO that supports the shoe shiners you photographed. How did that partnership begin?

Estol: My investigation to get inside the world of the shoe shiners led me to get to know one of the social organizations that have been producing the monthly newspaper Hormigón Armado for 16 years. Every newspaper sale helps nearly 60 families of shoe shiners to get an extra income.

I thought it might be interesting for them to create a special newspaper edition concerning discrimination that would be made through a participatory process and given out with a street flyer to raise awareness among common citizens. For me, this was a way to go in the opposite direction of what the media would have asked me to do in order to cover a similar story. Ethically, it was also important to try to make the production and spread of the projects useful for all of the people involved. The collaboration was based on providing images for the newspaper in a way that we could all take part in as actors and creators.

At the beginning, while the outcome was collaborative, I found the pictures were too similar to the photographic records of an NGO. I was more interested in leaving that kind of work and producing a different, more conceptual visual style and credit the group for creation. Together, we all decided that I would take the pictures for the monthly newspaper and the organization supported me for three years.

The shoe shiners stapled the newspapers in return for the copies they would sell. They sell 6,000 copies per month and understand the importance of showing good pictures, so they cooperated by working a few Saturdays on the project. I worked as a volunteer serving mid-afternoon snacks over the first month, and afterwards we started on the photoshoots and did some workshops in order to build the story.

© Federico Estol

© Federico Estol

Seikaly: You quickly rejected a documentary approach in favor of a conceptual one. You were also interested in collaborating with the shiners and the NGO that helps support them. With all of this in mind, I’m wondering how the visual language of graphic novels and comic books emerges as the narrative construct for both the workshops and the photographic series?

Estol: The idea was to start a joint project with them by developing a visual narrative that could dignify them as people, including the activity of handing out the newspaper on the street. We started by taking portraits in daily life, while cooking or sleeping so people could see them as regular citizens. Then we realized that wearing a ski mask was associated to something dangerous or negative—even terrorism—but they didn’t want to be photographed without the mask.

On Saturdays, the shoe shiners have group meetings to discuss content for the newspaper while having a snack. In one of these meetings someone brought a very old edition of the newspaper that had a shoe shiner in a cape with the Superman symbol on his chest on the cover. That image awakened an interest to investigate the origins of that character and soon we discovered a close conceptual connection with shoe shiners. A few days later we succeeded in finding some Bolivian illustrators that were interested in conducting a workshop with us and explaining the foundations of the graphic novel.

Some group censorship was about showing people’s faces at home, because the people will ask why a photographer is taking pictures of you and usually the neighbors don’t know or even their own family.

We then organized a workshop to discuss the key parallels between the shoe shiner and the superhero. These included: using a disguise—the ski mask—to hide their identity; living a double life and concealing their job to family and friends; being persecuted by ‘enemies’ such as the police; using special tools (a shoe shiner’s box with cloth, brushes and shoe polish); having a hideout (the shoe shiner’s associations, where they keep their clothing and boxes safe, and wash before heading home); and finally, serving others by providing a service.

Then, all together, we built a collage storyboard on the everyday life of ‘Los Heroes del Brillo’—the ‘Shine Heroes’. This inspired the narrative for the final photobook. The pictures were taken during photoshoots in the cities of El Alto and La Paz, where we drove all over town in a minibus with the shoe shiners as lead actors. In Bolivia there is a local architectural style called ‘cholets,’ based on fantastical buildings inspired by the Tiahuanaco ceramics. These provided the perfect scenography to create a fantasy city we named ‘Brillolandia’.

I worked with them for more than three years, collaborating in a way that ended once the photobook was published. Our relationship still exists, as the social element of the work is very important to me. We finished producing the photobook, but we continue as collaborators on a permanent basis.

© Federico Estol

Seikaly: You raise important questions about racial inequity that is baked into Latin American societies. You also highlight the power of community in counteracting violence. Could you describe a memorable moment, something or someone who affected you?

Estol: Children without parents growing up alone shocked me. I met six-year-old children and 80-year-old ladies working, so this is a life doing the same job. It is an honest way to earn money. I’ve put my effort into communicating and changing the discrimination they suffer.

Seikaly: Has your experience with this group in any way influenced your perception or definition of “brotherhood?”

Estol: They have a deep brotherhood, and wearing the mask unites them. It also reinforces discrimination. They are subject to misperception, but they fight that together. Brotherhood is a family without blood bonds, and these guys are a good example of that. The 60 shoeshiners who work in this project are a street family and share a common goal: live for the work they love without any problems.

© Federico Estol

Seikaly: Your project is clearly a social action; it fits into the genre we are used to calling engaged photography. Has that subject always interested you?

Estol: This is my first project using the community-based visual storytelling philosophy. I’ve worked as a community developer in small towns for the Uruguayan government since 2005. I use Paulo Freire’s pedagogical approach, which I learned in a course offered by the Franciscan church in Uruguay. Popular Education introduces the problem-posing concept as an instrument for liberation that involves a new relationship between teacher and student.

In this project, I try to do the same; forge a new relationship between the artist and community that centers their needs. We create the narrative together, centering the goals of the group, not the photographer. It’s a slow process, but the results are great.

© Federico Estol

Seikaly: What is the significance of mirrors in this project?

Estol: In these pictures, the mirrors work as special shine power tools. The most challenging aspect was to produce these special effects on a low budget and without post-production to be more authentic. The inspiration for the shoe shiners came from dragon ball cartoons and other Japanese comics.

The picture is most loved by the collective because of the La Paz citizens saying thanks to the heroes for saving the city by cleaning their shoes. This is an impossible picture to take in reality but sometimes fiction can be more powerful to change the discrimination act.

© Federico Estol

Seikaly: Congrats again on being a 2021 Critical Mass finalist. Understanding that it was a significant investment of time and money, what motivated you to apply?

Estol: The platform is really great and this project is well known in Latin America and Europe. For this reason, I applied to Critical Mass, to show this experience in the USA.

Seikaly: Aside from this Humble Arts Foundation interview, have opportunities come out of Critical Mass?

Estol: Yes many opportunities we get the solo show award of Blue Sky Gallery and this April we have the exhibition in Portland during the Photolucida review 2022.

Seikaly: Congrats! Has being selected for the Critical Mass Top 50 of 2021 influenced how you think about making work, or your creative process overall?

Estol: For me, Critical Mass is an open format platform and to be selected is an accomplished mission because all the projects are in this way of contemporary expression in the 21st century.

Seikaly: Thank you, Federico!