Sterile, Wounds Need Air, 2020. © Camilla Jerome

Camilla Jerome has lived with multiple chronic illnesses, most of which were un- or misdiagnosed, for 15 years. At 30 years old, that’s half of her lifespan. For nearly a decade, she’s used photography and video to process and better understand these experiences.

“It’s all in your head” or “It’s not that bad” and other dismissive phrases are familiar to the RISD MFA candidate. This kind of medical gaslighting has been reported on with greater frequency, but the trouble persists. To comfort herself, Camilla Jerome has cultivated numerous creative projects that convey both her struggles with institutionalized medicine and the personal victory she finds in trusting her pain response.

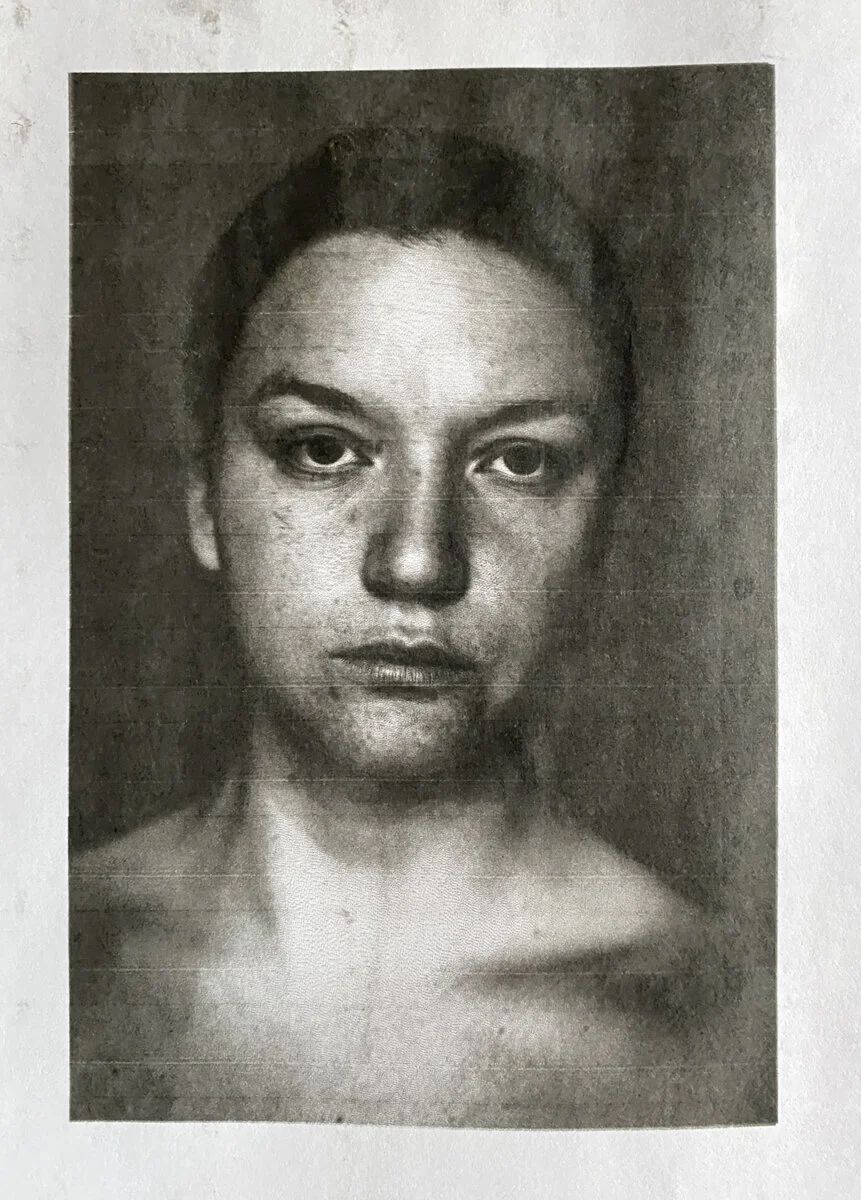

I am particularly moved by the image Sterile. Though the title refers to Jerome’s experimental attenuated bleach wash that renders the print’s surface brittle and vulnerable, it abstractly calls up the social and personal struggles and alienation many women navigate related to reproductive health. The image is part of her series Wounds Need Air – a quiet, gut-punch paean to survival.

Following our conversation during Filter Photo Festival’s early February virtual student portfolio review, Camilla and I reconnected to discuss her work and the experiences that inform it. We dig deeper into her thesis work, talking about making invisible disabilities visible, and the necessity of self-advocacy.

Roula Seikaly in conversation with Camilla Jerome

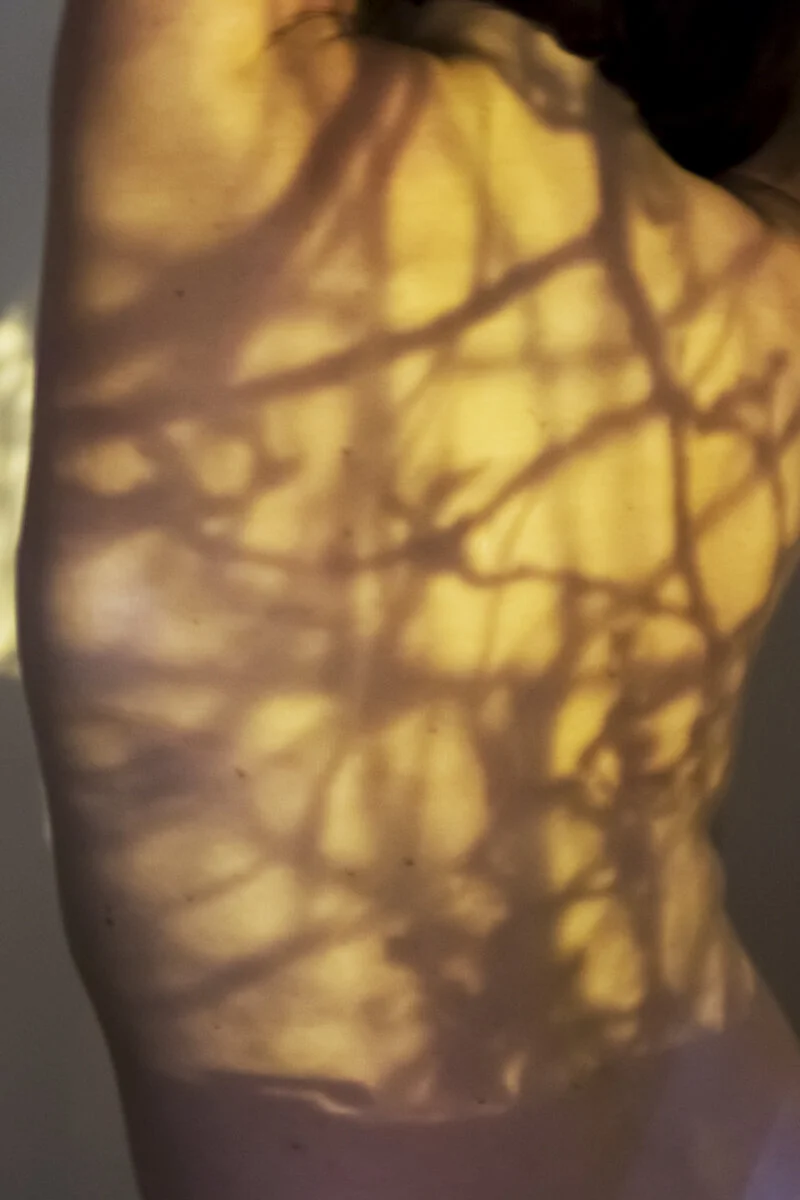

Serpentine, from the series Wounds Need Air, 2020 © Camilla Jerome

Roula Seikaly: How do you decide what to reveal, or conceal, about your disability?

Camilla Jerome: My artistic practice has grown alongside my disability. Over the years I have created a self-revelatory practice through exposing private feelings and ongoing physical issues, and this process has served as a therapeutic expression to find my own identity and purpose. Sometimes it is more of a subconscious decision and I follow my intuition, other times making art about my current symptoms helps me move through the discomfort, and then there’s the times where I just scream because I can no longer conceal my reality. I’m oftentimes more ready to reveal aspects of my disability through my art than I am vocally.

Seeing and Believing, from the series Patient, 2020 © Camilla Jerome

Film Stills from Show Me Where It Hurts, from the series Wounds Need Air 2020 © Camilla Jerome

Seikaly: In the Wounds Need Air project statement, you describe your body as a “fluid mode of being.” Is photography the ideal media to portray your medical challenges for its malleability, its “fluidity?”

Jerome: Absolutely. I love that I can go from using my iPhone camera, to using my Fuji 6x9, to pinhole, to dipping my feet in cyanotype and walking on canvas. I can constantly be creating and making visual notes for myself no matter what my physical and emotional energy is.

For the last year, I have been making work out of my bathtub, the same tub that I rely on to soak and soothe my joints and muscles. I collect the water from my baths and use it to develop 4x5’s and mix cyanotype. Art and water have provided me constant relief throughout this journey.

Photography, in this sense, is able to meet me more than halfway and I am thankful I can approach this work on my own terms. Although, it is ironic that photography is my medium and diagnostic imaging (MRI, CT scan, X-ray et al.) has failed me countless times in the search of diagnosing and naming my disease(s).

Seikaly: Could you describe the process “tests” to which you subject your images, including the bleach wash used for “Sterile.” Why is that an important aspect of this work?

Jerome: At the time I was in a photographic rut. Holding the camera I felt like I was making pictures that I had made a thousand times before, which was incredibly stressful during my first year in grad school at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

I had gone to see Liz Deschenes give a lecture at Brown where she told a story about a collector who had bought a piece of hers and later wanted to return it because it no longer looked the same as when they had bought it. She was kind and took the piece back and offered them something else of hers in exchange. But she laughed and explained that the collector had missed the point entirely--that change is at the center of all her work. “A conservator’s nightmare,” she joked.

And so my “tests” or “experiments” began about a year ago when we were in quarantine. I was in my second semester of grad school and while it was pass/fail I still had to produce work. Covid put my first solo exhibition for my project Anhedonia on hold, indefinitely. I had all my final prints at home with me because they never made it to the framer. I had critique the next day and nothing to show. I was in a frustrated rage at 7am on a Sunday, pacing around my one bedroom apartment while my partner slept. We had about half a gallon of bleach left and so print after print went into the tub. I would pour a quarter cup of bleach onto the print. It would sit there for whatever amount of time I felt good about. And I couldn’t see what the bleach had done until I began to wash it with two drops of soap and water.

While the process was freeing and exhilarating the unknown end result during such a mundane time felt familiar and in the end I was just erasing myself. Maybe a past self that no longer felt familiar, but no matter how much of myself has changed I am still here. Now I have this print, a unique object that lives, its emulsion slowly flaking, the ink slowly fading. “Sterile” was the only piece that felt successful to me from that day.

Sterile, from the series Wounds Need Air, 2020 © Camilla Jerome

Imminent, from the series I am Evidence, 2015 © Camilla Jerome

Seikaly: “Wounds Need Air” is the series we discussed during our Filter Photo Festival portfolio review in early February. Could you talk about your other projects - Anhedonia, Patient, I am Evidence? Is it accurate to say that you use photography to understand your physical challenges, and how industrial medicine often pathologizes women’s bodies?

Jerome: I think that has always been an aspect to my work whether I knew it or not. All of my work seeks to make the invisible visible and I often turn to photography to express myself in ways that words do not suffice. In I am Evidence I was obsessed with photographing my parents and our relationship as each of our bodies were changing. It wasn’t until later, towards the end of the project, about four years in, when I came to realize that I was also documenting our three separate battles with disease simultaneously.

Anhedonia started slow and then happened all at once. It was my first project out of undergrad and I had just had a serious car accident that left my car totaled. This is when my pain took on a different presence, becoming so embedded in my everyday life as to take on its own personality. She (my pain) went from being out of sight out of mind to a constant reminder that demanded my attention.

Patient is a new series, and the concept really solidified when I started examining the double meaning of the word itself. On the one hand you have the medical term, which brings to mind an individual at the mercy of a flawed system. On the other, you have an adjective which suggests tolerating delay without fuss. The work is a meditation on healing the body, and as much as it sounds like a cliche, the process of creating these images was both a journey and destination. My intuition told me to switch to black and white and use a camera with a rangefinder, allowing me to relinquish some control over picture making and embrace happy accidents.

Sunrise Swim, from the series I am Evidence, 2014 © Camilla Jerome

The Sting, from the series Anhedonia, 2018 © Camilla Jerome

Drip, from the series Patient, 2020 © Camilla Jerome

Seikaly: You’re also a fashion and lifestyle photographer. Could you talk about working in an industry that normalizes uncomplicated reproductive/women’s health when that’s not your personal experience?

Jerome: The commercial industry needs to be hiring more BIPOC, women, trans folx, and non-binary people because representation matters. In 2019, the New York Times released a gender statistic of commercial photographers, 51% men to 9% of women working in the industry. That’s incredibly appalling and prejudiced. And there have been countless times where I am the only woman on the photo team. I am six feet tall and can hold my own, I had to prove myself countless times to get my foot in the door. It was also an extremely ableist environment--working as a commercial photographer and photo assistant broke my body and looking back I’m ashamed of the things I put up with and said yes to.

There would be days that I felt I wasn’t able to leave set to use the restroom if there even was one accessible. One time while shooting on location my period bled through my underwear and pants. I didn’t have access to a bathroom until lunch or until the shoot was done. I was the only woman on set with no tampons or pads. Fortunately, I was dressed in the all-black photo uniform and no one noticed. No person should ever have to experience that and I did, in silence. But no more. We have entered the time of truth-telling and it’s time for all of photography, from fine art to commercial to documentary to photojournalism to wake up to this reckoning for inclusion and representation.

Nervous System, from the series Anhedonia, 2018 © Camilla Jerome

Diagnosis, from the series Wounds Need Air, 2020 © Camilla Jerome

Seikaly: You mentioned that you’ve been definitively diagnosed after years of medical trial and error. Do you think that knowledge will influence your ongoing or future photographic projects?

Jerome: I think it already is. Every new diagnosis whether large or small helps me to create a vocabulary around my work and my work helps me process the new information. So far, my major diagnoses have been Crohn’s disease, endometriosis, fibromyalgia, sleep apnea, depression, and anxiety. However, despite all of this, I still feel deep down that it's still not the entire picture. It’s been fifteen years, which is half of my life, of living with chronic pain and the unpredictability of chronic illness.

I’m slowly peeling back the layers with my own research about my symptoms and the greatest lesson I’ve learned is to trust my body, to trust my intuition, and that if people aren’t hearing you, say it louder. For a very long time, doctors led me to believe that my lived experience was false and that my day-to-day suffering was self-inflicted.

I separated my mind from my body like one was betraying the other but I am one being and I am whole. What I do know is that doctors’ egos, ignorance, and misogyny have caused delayed diagnoses of complex diseases for which there is no cure. The silver linings in this situation are the trust I have gained for my own instincts, my ability to persevere through countless abandonments, and most of all, the steady embrace of my wonderful family.